We used to worry about value for money

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

As the state has been reducing its contribution to students’ higher education by choking maximum fees, reducing grants and fiddling with loan terms, the debate about “value for money” has slowly been shifting from one centred on students to one centred on the taxpayer.

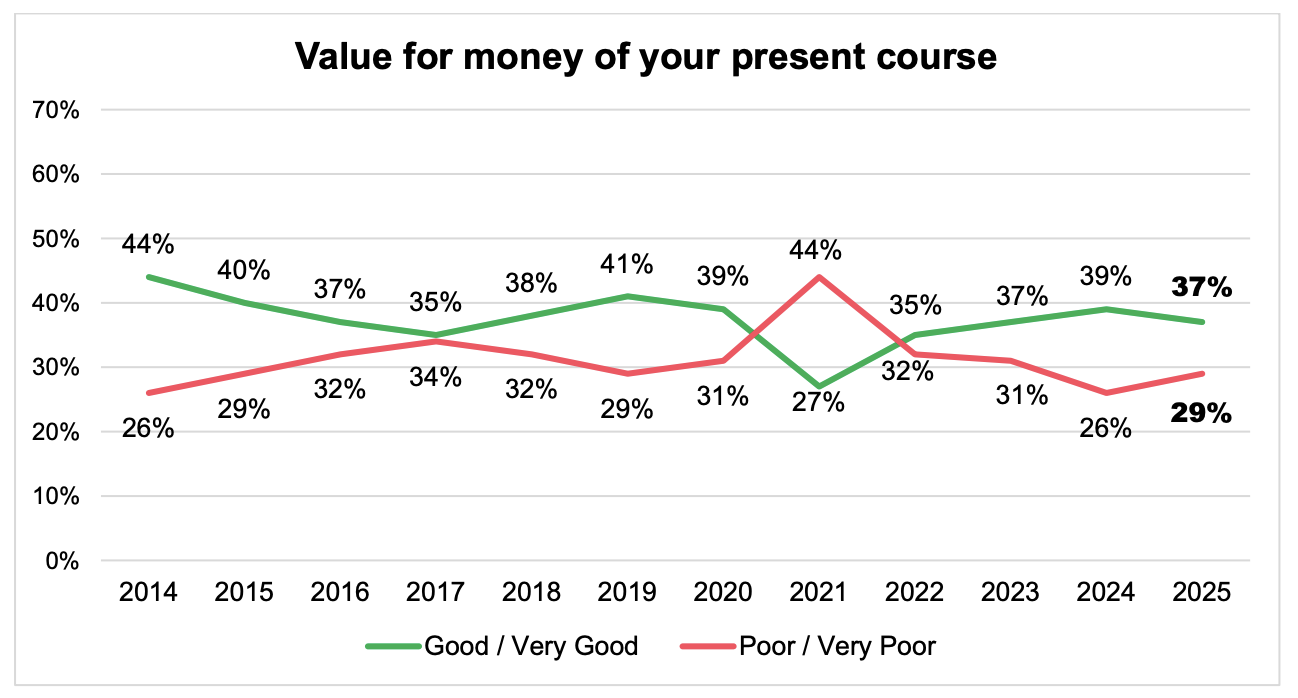

That may or may not explain the consistently poor scores for VFM that higher education has been getting in the HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey – which is back on the slide after its post-pandemic recovery.

That chart actually hides a number of much worse scores. Only 30 per cent of those on nine or less contact hours rate VFM positively. Only 29 per cent in non-university halls give a thumbs-up. Disabled students are less happy than others, anyone on a sub-degree course is less positive than the average, and care experienced and estranged students are down on 26 and 22 per cent positive respectively.

And there’s a very strong correlation between having expectations met and VFM in the underpinning data tables.

Bringing it back to the surface this morning, the QAA’s Student Strategic Advisory Committee (which unlike OfS’ Student Interest Board and Disability in Higher Education Advisory Panel, actually says things once in a while) has published a short report on the issue.

The small poll underpinning the report finds that while tuition fees remain the top concern, students define value primarily through three key factors – teaching quality and resources (they want current, industry-relevant content delivered by actual lecturers rather than endless self-study), employment outcomes (developing transferable skills for a competitive job market), and comprehensive support services that justify the overall package cost.

The material partly concerns things in universities’ gift and things outside of it. In the SAES over repeated years, there’s quite a strong correlation between VFM and social class, and we’ve seen storing correlations with cost of living impact on respondents too. In 2023, of those impacted “a lot”, 45 per cent thought their course was poor value, whereas for those not impacted much or at all, just 17 per cent said that value was poor.

Value is often about the extent to which students feel able to hit the expectations and norms set for student life, and the time to take advantage of it.

For QAA’s SSAC, the findings expose a problem in how the sector discusses value for money – there’s no agreed definition being used across policy and quality assurance, which the report argues leads to poor quality courses escaping proper scrutiny.

Its recommendations are pretty simple – co-produce a single definition with students, fund universities properly to deliver what students actually want, and ensure equitable access to opportunities rather than promising extracurricular experiences that only privileged students can afford to take up.

Do you remember the time

For England, I’m old enough to remember when the Office for Students (OfS) was concerned about Value for Money – a process which culminated in the publication of a whole strategy on it, still quaintly linked to on this webpage despite having ran out in… 2021.

That had been a long time coming – but was actually kicked off via some student polling I was involved in during the regulator’s set-up phase. Former CEO Nicola Dandridge commissioned it when OfS was just Nicola and a PA hotdesking in HEFCE, and you can still find the launch of the findings on YouTube here.

We found very similar things to the QAA’s poll back in 2017. That poll of over 5,000 students found “hygiene factors” as essential baseline conditions students expect, like adequate contact time, quality teaching, and transparency in costs – when these were lacking, dissatisfaction arose.

“Motivator factors” were aspects that added value and satisfaction, like personal development, career prospects, and transformative university experiences. But students struggle to appreciate these motivators unless hygiene factors are first met. In other words, motivators drive satisfaction only after the basic expectations (hygiene) are fulfilled.

In the end it took OfS another 18 months to cobble together a VFM strategy – but it need not have bothered.

Expectations not met

In the January 2013 grant letter from the government to HEFCE, Vince Cable and David Willetts argued that:

…under the reformed HE system, students will legitimately want to understand what their fees pay for. This places the onus on institutions to provide clear information and to be able to demonstrate value for the fees charged.

HEFCE responded later in the year by commissioning work that found there was interest in this type of information, but what was published was limited, not easy to find, and often difficult to understand. It then argued that providers should make the information more accessible, position it clearly on institutions’ own websites, make it clear, provide a useful level of detail, and that data should be comparable – making it possible for students to compare “financial information for different institutions and over time”.

HEFCE went on to issue optional guidance to higher education providers, but little changed. In our 2017 polling, 22 per cent of UK-domiciled students “definitely disagreed” that their tuition fees were value for money with only 7% “definitely agreeing” that they were.

Universities UK research found that students “expressed frustration that they could not see a breakdown of costs attributed to tuition fees”. 88 per cent of students said that seeing a breakdown of how their provider spends its fee income would be helpful in assessing whether it provides value for money, and in a 2019 HEPI survey, 73 per cent of respondents said that they had not been provided with enough information on how their fees are spent.

On that, the OfS VFM strategy said this:

All registered providers must have adequate and effective management and governance arrangements (condition E2). These arrangements must deliver in practice a set of principles – including being transparent about value for money for students.

We have set out in our regulatory framework one way in which providers can demonstrate that they satisfy this requirement – by regularly publishing clear information about how they ensure value for money, including income and expenditure data.

Where we identify providers who do not comply with our requirements about transparency, we may intervene by requiring plans for improvement. We will issue further guidance to providers so that they better understand our expectations, and what they should be doing to meet our requirements for transparency.

Literally nothing has come of that, and the SAES doesn’t even bother asking the question any more.

There were also commitments to “monitor the availability of providers’ transfer schemes” (it last published stats in 2021), “further develop the TEF” (students found 2023 to be of “limited use” and it’s now all being reviewed “again”), to launch DiscoverUni (“I feel like there is definitely some very useful information on this page, but it’s quite hard to figure out what any of it means”), and my favourite:

We have committed in our business plan for 2019-20 to evaluate and report on the advice available to students about their rights as consumers.

Central in the 2017 work, this new QAA poll and the SAES is having expectations met – and the VFM strategy notes issues with hidden costs, course changes, contracts and websites needing “accurate, accessible and comparable information”:

We plan to produce further guidance for providers to ensure this.

OfS promises on consumer rights first appeared in an Autumn 2017 DfE-run consultation on OfS’ regulatory framework, which promised that OfS would undertake “further consultation on student contracts and student consumer rights” which was to look at whether OfS “should play an enforcement role”, and also “whether students would benefit from the use of model contracts with providers”.

OfS then said it would do so May 2018, revised it to September 2018, shifted it to December 2018, moved it to January 2019, delayed it to May 2019, planned it for July 2019, talked about it in November 2019, failed to do any meaningful enforcement during the pandemic, promised to “consult on an updated approach to protecting the interests of students as consumers” in its 2022 business plan, promised to “publish more information about our future approach to protecting students’ interests as consumers” in its 2023 business plan, promised to “consult on a new initial condition of registration relating to consumer protection, with a view to implementing any new condition” in its 2024 business plan (it only consulted and even then only for new providers), said the nomenclature needed to change last summer, and has now had the gall to promise it yet again in its 2025 business plan:

This will include consulting on a new ongoing condition of registration to ensure providers are treating their students fairly.

At this rate, OfS will launch a new approach on students’ consumer rights at the precise moment that pretty much every provider in the UK has completed making massive cuts to courses and wider services, hoping that students neither know their rights nor have the confidence to complain.

I’m reminded of the old SU elections adage – Vote for the candidate that promises the least. You’ll be least disappointed.

One question I’m forced to ponder is whether perceptions of value for money are the same as value for money. Is our only metric to prove that universities aren’t providing value for money that students don’t FEEL they’re getting value, or is there proof that their university degree doesn’t provide long term value for money?