The Augar review is back, baby. Just don’t about talk yourself

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

And as I’ve floated around the various fringes, receptions, stalls and launches, one thing has really struck me. It’s just how obvious some sector lobbyists are.

One of mine and Mack Marshall’s central bits of advice for SU officers is always to focus on people and issues rather than wins and work – the former looks selfish and narcissistic, the latter looks like you care, and generates both engagement and good reputational vibes.

Of course if you’re lobbying for universities, or schools, or housebuilding or industrial pipe bending equipment, it’s perfectly possible to talk about what you do and why the new things you might do are cool – just so long as you actually talk about the issues people face and the people facing them.

But that’s often not what happens. Whether you’re the boss of a pipe being firm complaining about an obscure bit of regulation that holds back investment, or a private HE provider complaining about the value of foundation year fees (while running a business whose profits could easily cover the cut and more), you may not realise quite how obvious you’re being. But you are.

As such, higher education finds itself in a tricky position – but it’s a differently shaped difficult position to that which it’s been in previously.

I’m all out of faith, this is how I feel

Just below the surface, Labour is torn between its working class, economic roots and its increasingly middle class, socially liberal membership.

Under the Conservatives, universities found themselves accused (however unfairly) of pandering to the working classes – letting in those who would have been better off learning how to be a brickie or a sparkie than studying gender studies at Gravelton Poly.

Now under Labour, the leadership is so scared of coming across as having avocado on toast for its breakfast that it can’t stop signalling that it cares about those “left behind”. Ben Ansell has a terrific new Substack post up that describes it like this:

The Andy Capp in their head has left containment and is making increasingly incessant demands.

It leaves universities in another difficult place. The main socially liberal middle base that already study or work in universities is assumed to be in the bag at elections, and just as keen to cosplay over its guilt as Labour’s leadership.

So given few want to tack too far towards the social illiberalism of Reform, that leaves the sector needing to find people who really have been left behind – and the good news is that we don’t need to make myths to find them.

Phillip Augar’s ghost was spotted at the event somewhere this week – and given a key member of his Post-18 review panel (Nottingham Trent VC Edward Peck) was retained as government student support champion and then took up his current role as OfS chair, we should remind ourselves of the review’s introduction.

There, those left behind were the 50 per cent of young people and older adults who do not attend university and instead rely on further education colleges for post-18 learning. They receive significantly less public funding (Augar quoted £2.3 billion for 2.2 million students) compared to university students, face lower-paid teachers, outdated facilities, and complex funding systems.

And despite being vital for upskilling in a changing labour market, they suffer from decades of neglect, limited political representation, and reduced societal prestige. Their sector – principally FE – remains demoralised and under-reported, with little improvement despite multiple reviews.

It’s why Starmer repeated the “Cinderella sector” line when talking about FE. It’s why he “scrapped” the 50 per cent target.

The very good news for all sorts of reasons was the signalling redefinition of “higher level” to include apprenticeships in the new 70 per cent target. It probably didn’t fit the speech to also say “and we need more high level technical at Levels 4 and 5” but that’s what’s going on.

As Torsten Bell’s Resolution Foundation report found before the election – Tertiary needs to expand, just not studying that and not studying it there.

Challenges and opportunities

It all leaves “the sector” facing three problems – but none are insurmountable.

The first challenge is to actually surface the vocationalism that is buried in existing HE, but that pundits and politicians seem to have struggled to find since 1992. It needs to be more than PR and the odd hard-hat photo op – see my write up of the Instituto Superior Técnico in Portugal for some clues on how to actually do it.

The second is to re-read Augar and remind oneself that policy has a strange habit of surviving beyond individual minsters and even governments. In both mood music and most of the detail, this government is finally getting around to implementing it properly – the LLE, Skills England, even maintenance grants. If the “sector” has thoughts on what it needs to deliver it, they need to manifest now. “But you promised not to level us down while levelling the rest up” is not the place to start.

The third is to find a way to talk about the pipe-bending regs or the foundation years cut or the international levy or whatever into conversations about issues and people, not universities themselves.

Jacqui Smith was at her best this week explaining who the Augar reboot was for. Starmer shone when talking about actual people he’d met. The sector was at its strongest when Salford VC Nic Beech talked of the the students struggling to afford participation in higher education – where his determination to allocate 10 per cent of professional services and technical jobs to students, his decision to support a major investment in student tutoring and his dedication to take catering off the corporates to improve range and pricing all sounded like real solutions to real problems faced by real people.

When one contributor in the Q&A was complaining about students taking all the housing, or another expressed shock at how expensive putting his kids through university had become, the “sector” should have had actual answers ready – many of which need to be rooted in taking much, much more seriously the negative impacts that increased HE participation has on communities, and parents.

Hitting the fan

Three other final reflections from the week. For all the decades of talk about FE being the Cinderella sector, it’s less affluent families and students in traditional HE that now run the risk of borrowing the costume. Care experienced students, student parents, those working 30 hours plus run the risk of donning the dress for Freshers week and Graduation Day but then returning to the serving quarters below.

Never has it been more important to demonstrate a deeper understanding of how difficult Keir Starmer might have found things if he was enrolling into Leeds now rather than in 1982.

The second surrounds 2024’s word of the year. Many of the fringe meetings were searching for answers on all sorts of problems facing the young – but they all seemed to route back at least for me, to enshittification.

It describes how platforms initially provide value to users, then shift to prioritising business customers over users, and finally extract maximum value while degrading the user experience – but the pattern now extends far beyond tech platforms (where the term originated) to the fundamental infrastructure of young adult life in the UK.

Whether pursuing higher education or entering work directly, young people find themselves as captive users of systematically degraded systems – universities that extract fees while providing diminished modular choice or employment prospects, gig economy platforms that extract labour value while offering minimal security, housing rental markets that extract maximum rent while providing minimal rights, and physical social infrastructure (pubs, cafes, youth clubs, public spaces) that has been either removed entirely or transformed into transactional environments that require constant consumption and the taking of ever-greater risks.

And some of it, for the sector, begins in that privatised cafe that students don’t use any more on campus:

The result is a compound enshittification where every major system that young people navigate – from housing and work to education and even dating and social connection – has shifted from facilitating successful adult life to extracting value from the unavoidable process of growing up, creating a generation trapped as users of infrastructure designed to exploit rather than serve them.

The sector needs to understand it, explain it, offer ideas for alternatives to it, and take as many steps as it can to not be participants in it.

But the final is just how siloed the sector still feels. More fringes and more VCs floating around is one thing – but the near-absence of academic expertise, management and students from debates on health, communities, the legal system, the climate, public transport or welfare reform or whatever compounds the sense of narcissism.

Universities have always had advantages over other sectors. As well as the provision of education, they are supposed to able to offer solutions to policy problems, and through those that are keen to learn and gain experience, student participation in finding and implementing those solutions.

A little more focus on participation, and a little less focus on provision, would do the sector the world of good.

Very witty.

Welcome to the world of the bureacratic enterprise and not the charitable college.

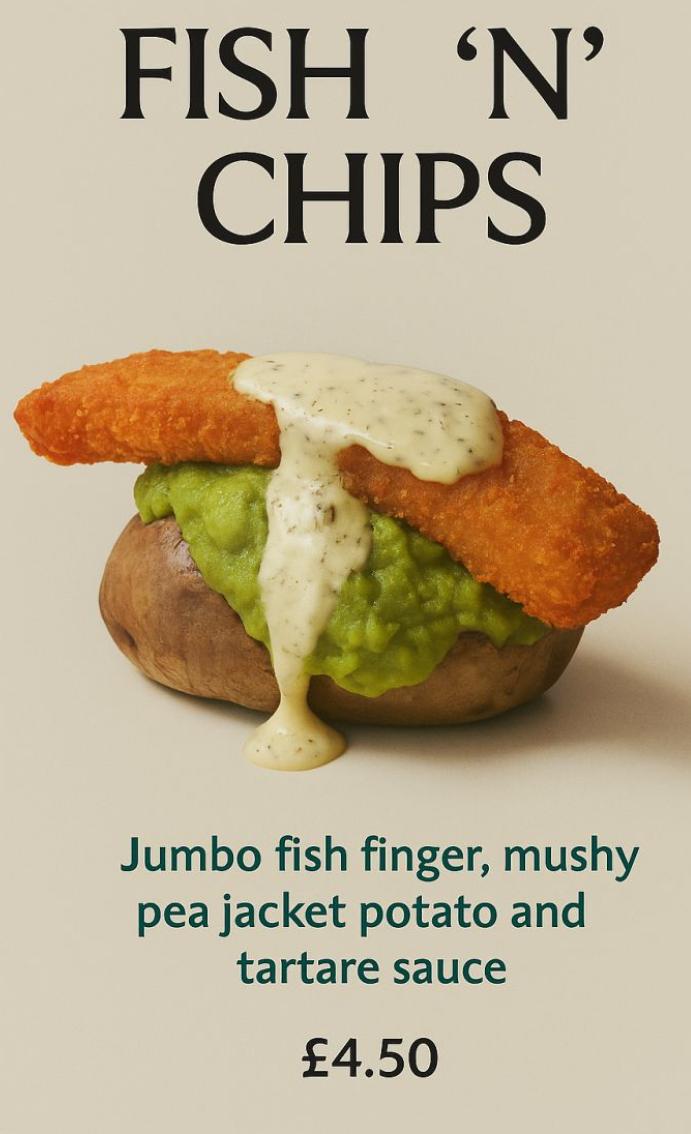

Is there a plate and knife and fork? Or is that extra?