International students and graduates are propping up the UK’s care system

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

Update: The Migration Observatory report that forms the basis of this article was substantially amended in May 2024 due to issues with the data. Read more here.

We know that students are more likely to be working during term time than in the past, we know that they’re working longer hours, and we’re deluged by (and providers increasingly held to account over) the percentages in work after graduation, and the proportions in what the labels (often inaccurately) describe as “graduate jobs”.

We also know, thanks to the HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey, some things about motivations for being in part-time (or, increasingly full-time work) during study – and the way that that bifurcates between students working to live or afford essentials, and students working to develop their skills or career.

What we don’t know so much about is the type of work that students are undertaking. That could matter quite a bit both for the ways in which it helps (or hinders) skills development, confidence or belonging, and may well also matter depending on how exhausting that work is and the subsequent impact on full-time study activities and outcomes.

So I was fascinated to see, in UCLan’s Student Working Lives project that we featured on the site yesterday, to see this chart – both because of the cliches it confirms, and the surprises it generates:

That was based on a single university, 270 student sample of those studying a range of business disciplines – so we clearly can’t draw national conclusions from it. But it does raise all sorts of questions about the economy (or at least sections of it) and its dependence on students or graduates.

The national Labour Force Survey is the ONS’ main study of the employment circumstances of the UK population. It is the largest household study in the UK and provides the official measures of employment and unemployment.

In the January – March 2023 iteration of the data, of the 825 full-time students in employment that filled it out, about 10 per cent were working in human health activities, residential care activities or social work without accommodation.

But like many other national surveys of ilk, there are questions over whether its sampling methodology properly captures students – especially those that are new to the country. And so we might speculate that the real number could be significantly more than that.

Entering the labour market

For better clues, there’s yesterday’s Migration Observatory report on international students entering the UK labour market.

It notes that for the 2020 and 2021 cohorts, the share of people switching to work visas rose sharply by the end of the first year after arrival – fifteen per cent (or 52,500) of the 2021 cohort had moved to a work visa in this timeframe. The previous peak was for the 2010 cohort, 4 per cent of whom were on a work visa by the end of the first year after arrival (10,000). Where those switches involve doing so before completing a course, that’s a “loophole” that the government has now closed.

It’s the graduate route that’s most interesting in the numbers. The share is up – that’s precisely what the route is supposed to do. But we don’t know what types of jobs people on the graduate route are doing, because the government has traditionally not collected statistics on most visa holders’ economic activities. It’s also too early to say how many will stay beyond the end of their graduate visa.

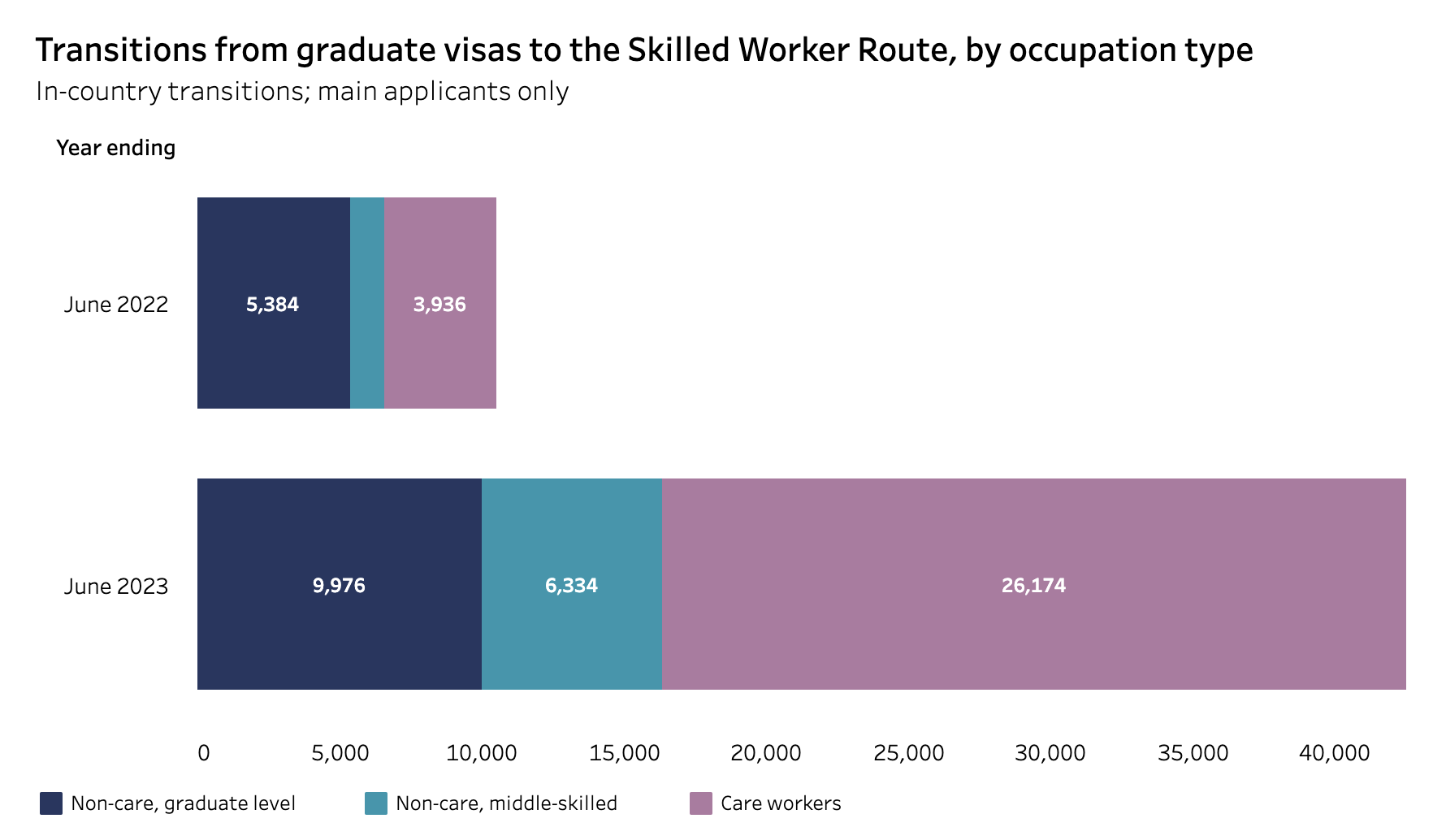

But where holders of a graduate route visa do switch to skilled work, we do know what that work is. And it’s a remarkable chart:

62 per cent of international graduates that moved from the graduate route to the skilled worker route in the year ending June 2023 became care or senior care workers – some 26,200, which is up from 2,936 the previous year.

That, notes the report, is a lot higher than the share of skilled worker route visas going to care roles for those who apply out of country – who by definition are unlikely to be international students.

For each of the two years in the above chart, we don’t know if the switch was made by someone in year one of the graduate route, or year two. But for a sense of this, in Y/E 2022, 66,211 graduate route visas were granted. And so we’d have to assume that a large proportion of graduate route visa holders are therefore also propping up the care sector, and thus that a large proportion of current students are propping it up too.

Either way, there’s a lot of graduates on the graduate route going into our care sector. And as the report also notes, changes to the salary threshold for the skilled worker route may well lead to a decline in the number of students switching into middle-skilled and graduate roles, given the care sector remains exempt from the new threshold.

As the report rehearses, those completing master’s qualifications that move into jobs that do not require them may see these skills atrophy. And it is possible that former international students will be less vulnerable to exploitation than people coming directly from abroad for care work “because they are more likely to have local knowledge and language skills” and can “scope out employers while on the graduate route without relying on (sometimes exploitative) middlemen”.

It does also mean that the number of non-UK citizens entering the care sector on work visas is some 34 per cent higher than previously thought – and higher still if the international students who’ve switched directly from study to work visas were included.

Neil O’Brien, MP for Harborough, Oadby & Wigston, framed the news in the slipstream of a continued critique of his, one that labels international student policy as the “Deliveroo visa scandal”:

Deliveroo visa scandal latest:

-Come as a student

-Flip to care worker

-Get citizenship

-Do whatever you want https://t.co/wewJ8IxKMM— Neil O’Brien MP (@NeilDotObrien) January 30, 2024

I think I would take a different view – that we seem to be funding UK HE on the backs of the wealth and/or debt of families from the global south, only to be trapping them in roles that the country seems to not want to pay properly once they’ve graduated. All while asking them to pay visa and NHS surcharges for the privilege, while being vilified in the press and by MPs, and topping up the pension funds of the landlords they rent increasingly scarce rooms from in the process.

If nothing else, on these sorts of numbers and with a social care crisis among the many crises engulfing public services, it’s perhaps unlikely that the government will take further steps to restrict the graduate route lest it further endangers a care system already on the brink. That that may well be a reason that the government backs off should hardly be a cause for sector celebration.