How to assess anxious, time-poor students in a mass age

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

We chuck a bunch of new restrictions, opportunities and things we’ve found from HE across the world at groups who then have to make sense of it all to think afresh about their strategy for the student experience.

It’s an exercise designed to unleash imagination and creativity – and there were some brilliant ideas popping up throughout the day on everything from credit acquisition to belonging, from cost of living to civic engagement – all in a context of tightening financial and student time resources.

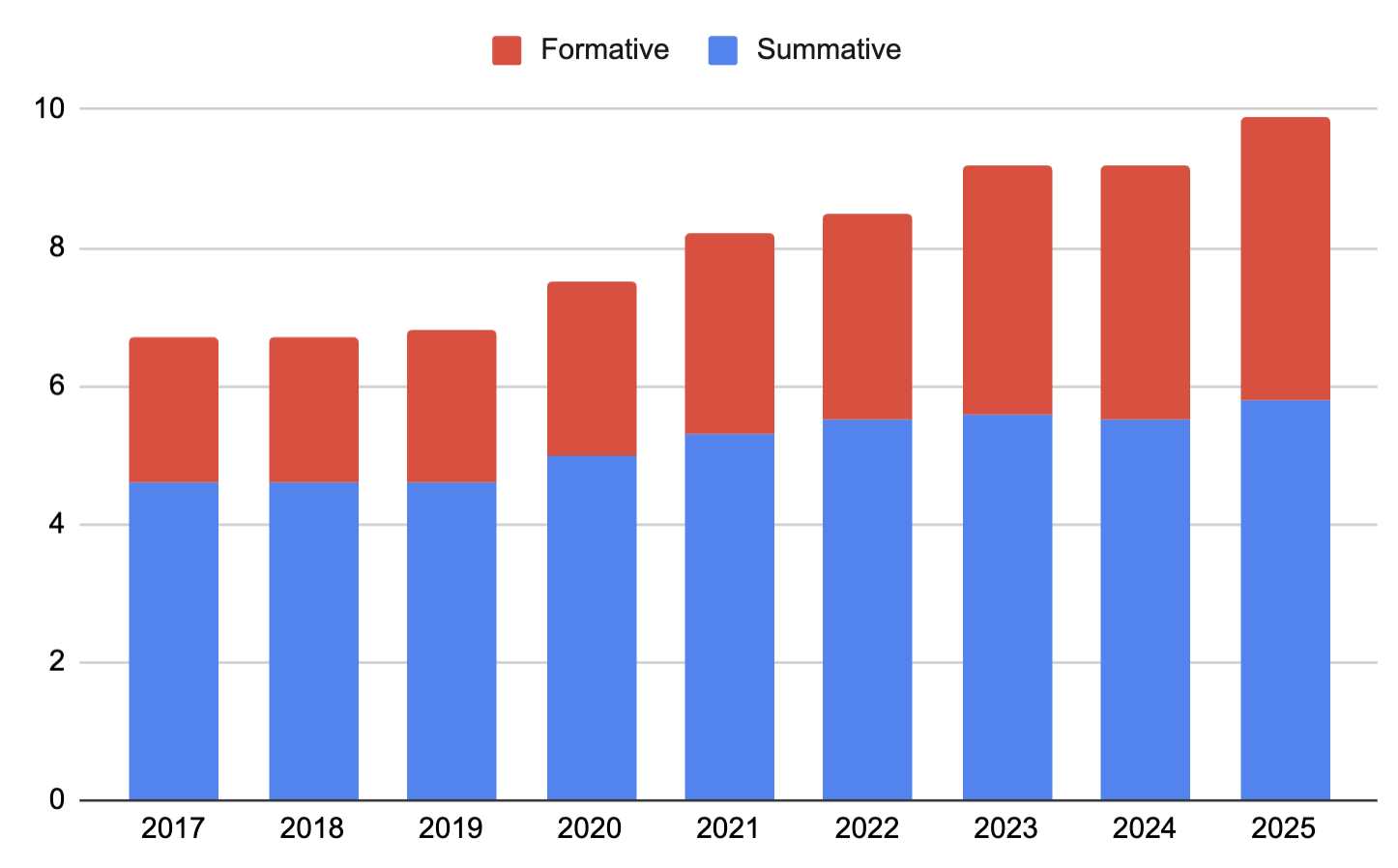

It’s lots of fun to facilitate – but in the background, on my mind all day has been this chart on assignments set in a semester in the HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey:

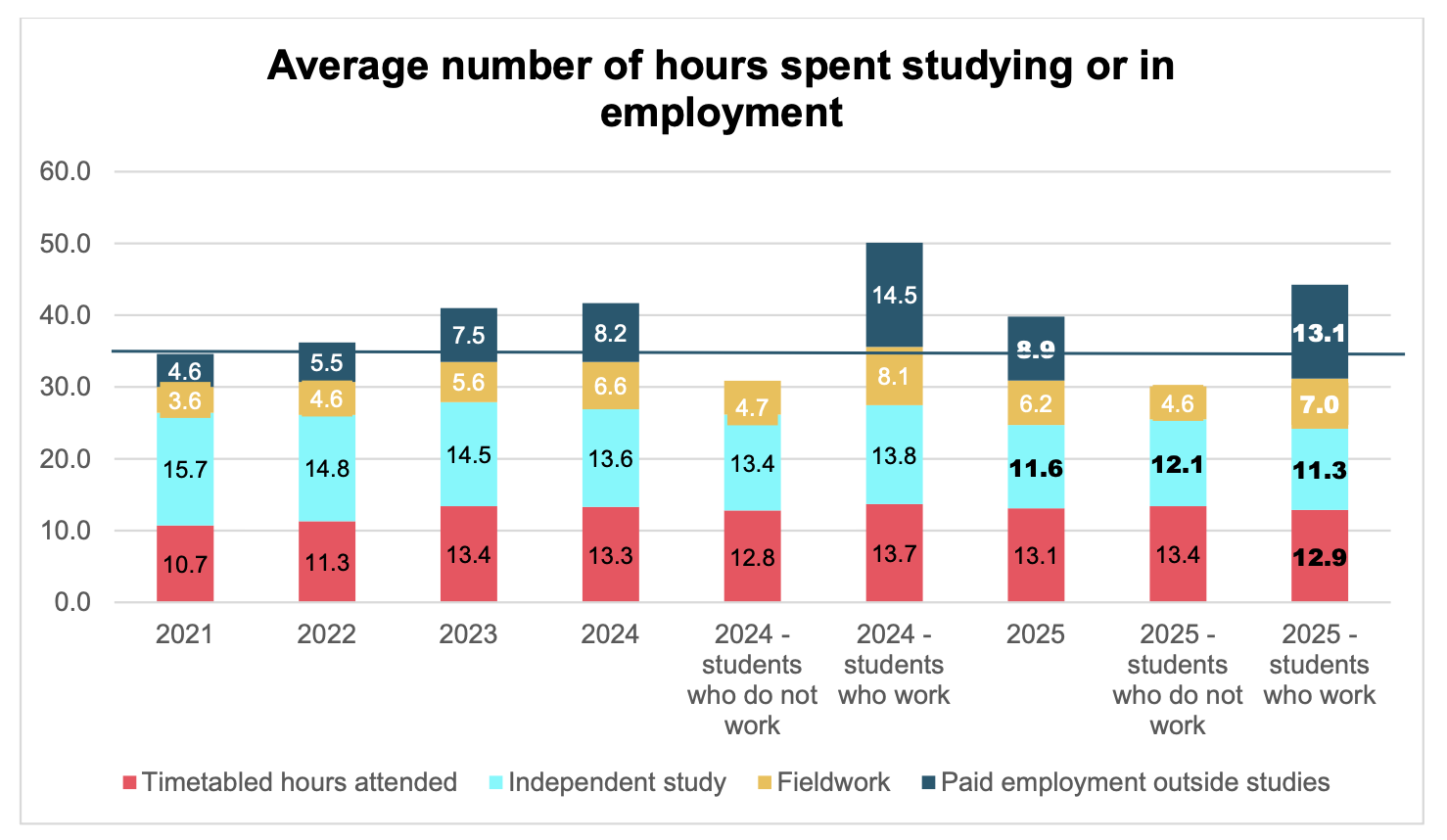

To be fair, that chart doesn’t appear – I’ve stacked formative and summative assignments to show a total. But when thought about in the context of this chart, there’s an obvious problem:

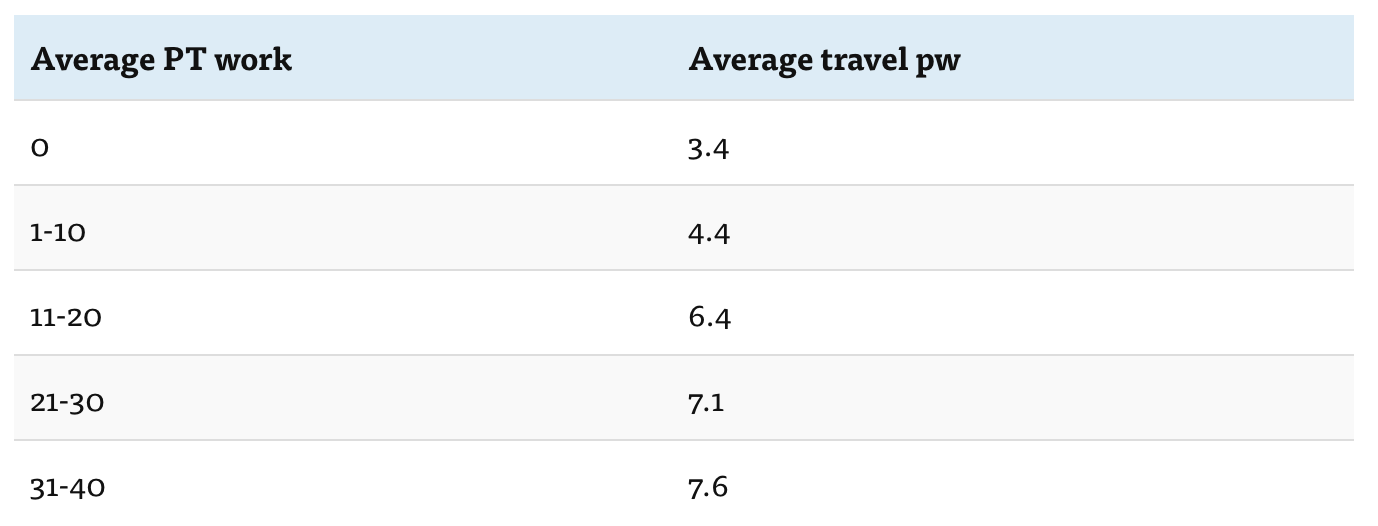

One thing I’d add about the rise in students undertaking part-time work during employment (which SAES has at a record two-thirds of UK FT UGs) is that the above chart misses the time students spend getting to (and from) work.

When we looked at time spent travelling per week a couple of years ago in our Belong polling, we found these numbers to add on:

As the groups were beavering away with post-its, I got a few minutes to dive into some of the splits on the assessment figures.

By institution type, the biggest increase (when adding formative and summative together) has been in the “other” category on 3.92 since 2020. Both pre and post 1992 universities have increased by 2.5 ish apiece, while the Russell Group and specialist providers have increased by 2 ish.

If nothing else that plays into a bunch of prejudices and assumptions I hold about change and innovation in assessment.

The subject splits are fascinating. Arts and Humanities students are completing (or not) 4 more assignments per semester since 2020, STEM students 5, Social Sciences just under 6 and Health over 6. Health! As if they have spare time!

Down at subject codes, things are even more interesting. Maths students – pretty much no change since 2020. Famously time-rich Medicine, Dentistry and Veterinary students – roughly 7.5 more assignments each. What’s going on there?

Of course, we’re a) looking at what students say rather than what has actually happened, b) they all come from different start points, and c) we can’t see what’s been dropped – the working assumption being that the sector has been moving away from “high-stakes” exams and towards continuous assessment.

Notwithstanding how faulty (and short-lived) some of the pandemic-narrowing of the attainment gap narratives have been, it’s clear that, in good faith, people have been responding to a range of agendas – stuff like more diverse assessment methods playing to different strengths, the idea that take-home assessments are allowing students to demonstrate deeper understanding, and reduced time pressure benefiting students with some disabilities or anxiety.

But my sense talking to participants from a range of universities today is that while universities have been variously successful at driving assessment reform at the module design level, there’s been little thought about compound impacts.

And when those compound impacts are combined with the crunch from part-time work, commuting and so on, it becomes pretty devastating for students’ health.

One thing not covered in the main SAES report is that applications for extensions are up at a mean average of 3.05 , up from 2.37 in 2022. For students without employment, this year’s figure is 2.33. For those working full-time, it’s 3.43.

I’ve talked about so-called “extra time” before – it assumes that students have spare time, just later on. But for many, it just creates a multi-car pile up – not to mention the impact on staff of both more assignments to mark, more extensions to approve, and so on and so on.

What’s going on?

What was especially interesting, though, about various of the side conversations I’ve had today has been partly about anxiety, partly about the difference between reacting to and engaging with students, partly about the whole notion of “high-stakes”, partly about the difference between “production” and “performance”, and partly about what’s going on with academic integrity and skills.

On the first of those, both in my family life and in my professional life (which involves a lot of working with student leaders and reps), it’s always very tempting to avoid activity and conversations that I know others will be anxious about. And no, I don’t think it’s “character building” to just throw people in at the deep end anyway – that’s why, knocking on 50, I still can’t swim.

But responding to high levels of anxiety without avoiding can be done – baby steps, gradual build, doing things in pairs, and showing people clearly what will happen are all things we know work. A sector whose underpinning assumptions remain that the entry system produces students who are “ready” to be one may well still be at fault.

On working with students, over in students’ union land there’s an ongoing conversation about the balance between being student-run, student-led and student-researched. Both with SUs and between SUs, there are real differences between a) activities/decisions run directly by students, b) activity where the priorities are set by them but a service or activity may be delivered by staff, and c) activity where decisions are led by the research or polling on behalf of students.

Things like the availability of data, the unreliability of old representative-participation models, the pressure on students’ time and a desire to professionalise and reduce risk have seen students’ unions shift slowly from a to c over time. And there’s been some healthy reflective debate about whether where we’ve got to is affordable now, and what’s been lost in the process.

But if I think about the way the sector has responded to students on assessment, it may well be that there’s been a reaction rather than a response to students’ concerns over exams and high-stakes assessment.

I’m not suggesting that when students say “I hate exams” that we should adopt a “but we know best” attitude. I am saying that there’s a real danger that in reacting to preference, there may well have been a failure to engage students in sophisticated conversations about the aggregate impacts and trade-offs.

On the stakes thing, I often talk to student leaders and SU staff about the reasons why the stakes are so high. For some, exam pressure will always be an issue. But we choose in the UK to make many exams “one shot”. There are plenty of HE systems that allow students to retake exams a couple of times, without penalty, even if they don’t fail. Easily 8 out of ten of those I talk to say “oh, that would be OK” – in many cases, the stakes are high because our weird assumptions about “first attempts” make them so.

All assessment suffers from testing talent in and preference for the design rather than the thing it’s supposed to be assessing. But the production v performance thing is interesting because of the differences in how “load” play out.

If I think about the difference between being asked to pitch up somewhere on a panel, and appear somewhere and deliver some slides, my nervousness about not having an answer to X always means that on instinct, I prefer the latter. I feel more in control.

But when I have a week where I’m due to deliver 4 or 5 presentations rather than taking 4 or 5 calls or being on panels, there’s no doubt that the aggregate impact on my stress levels and the time spent on production is heavier than a week of raw performance.

And there’s a future issue. I’ve heard many lament that exams are not the sort of thing that students will do “in the real world”. Meanwhile plenty of SU staff are both struggling with student staff recruitment because of the volume of AI-assisted applications, and starting to use AI in their work when producing things.

The academic integrity issues with “production” are well rehearsed. We will never again be able to trust something that is produced and later graded as a symbol of learning.

But what’s becoming clear is that not only is that true in the world of work too, it’s changing work and what is valued at work. The “production” of a report or presentation or “deliverable” is rapidly getting easier – and that’s either freeing up time to be more human, or creating environments which are starting to value performance, participation or engagement at work more than they are the production of a thing.

That isn‘t to say that some kind of lazy return to traditional paper and pencil exams is the way forward. But it is to say that reducing the height of the stakes of, and causing students to become more comfortable with demonstrating their intellect through encounters, interactions and moments rather than the production of something shiny over time, would almost certainly be good for their health now – and for their lives later.