Do better student housing rights hit supply of beds? It doesn’t look like it

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

The landlord lobby quote it endlessly, student housing charity Unipol has said it repeatedly in blogs and evidence to Parliament, the Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee reckon it’s true, and even former OfS boss Nicola Dandridge (now on the University of Glasgow’s Court) repeated it on the Wonkhe Show.

The story goes that the cause of the student housing crisis across several university cities in Scotland has been one of declining supply following its tenure and renting reforms in 2016. That saw a switch to open-ended tenancies, finite and reduced means of repossession by landlords and a 28 day cooling off period for tenants at the start of tenancies – all not dissimilar to that which is being proposed in England.

Unipol argues here, for example, that in Glasgow, the contraction of off-street student HMO accommodation meant that many more students rented PBSA bed spaces during the year and this means that many fewer PBSA bed spaces are available for new first year students:

This problem will be creating significant educational disruption for Scottish students who are unable to rely on securing accommodation in line with the academic year, increasing homelessness and sofa-surfing.

Other than anecdote this all seems to route back to a Scottish Government commissioned review of student accommodation as part of its wider look at Purpose-Built Student Accommodation (PBSA):

It is now widely accepted across the sector that as a result of the new tenancy and the experience of Covid-19, private landlords who hitherto had been content to let to students are now moving away from that market and looking for more long-term tenants with less chance of void periods. The evidence from Glasgow and Edinburgh appears to suggest that this is shrinking the available supply for student HMOs and putting upward pressure on rents.

The problem is that even the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence, which was responsible for the report, has since admitted that the evidence is “anecdotal and/or qualitative”, but it is “reported widely” and is “a rationalisation generally held across different perspectives among people working within the student accommodation sector.”

I can see why it suits all sorts of people for it to be true, but I’ve been wondering if is – and following an FOI request to the Scottish Government on dwellings attracting the student council tax exemption, I’m not so sure.

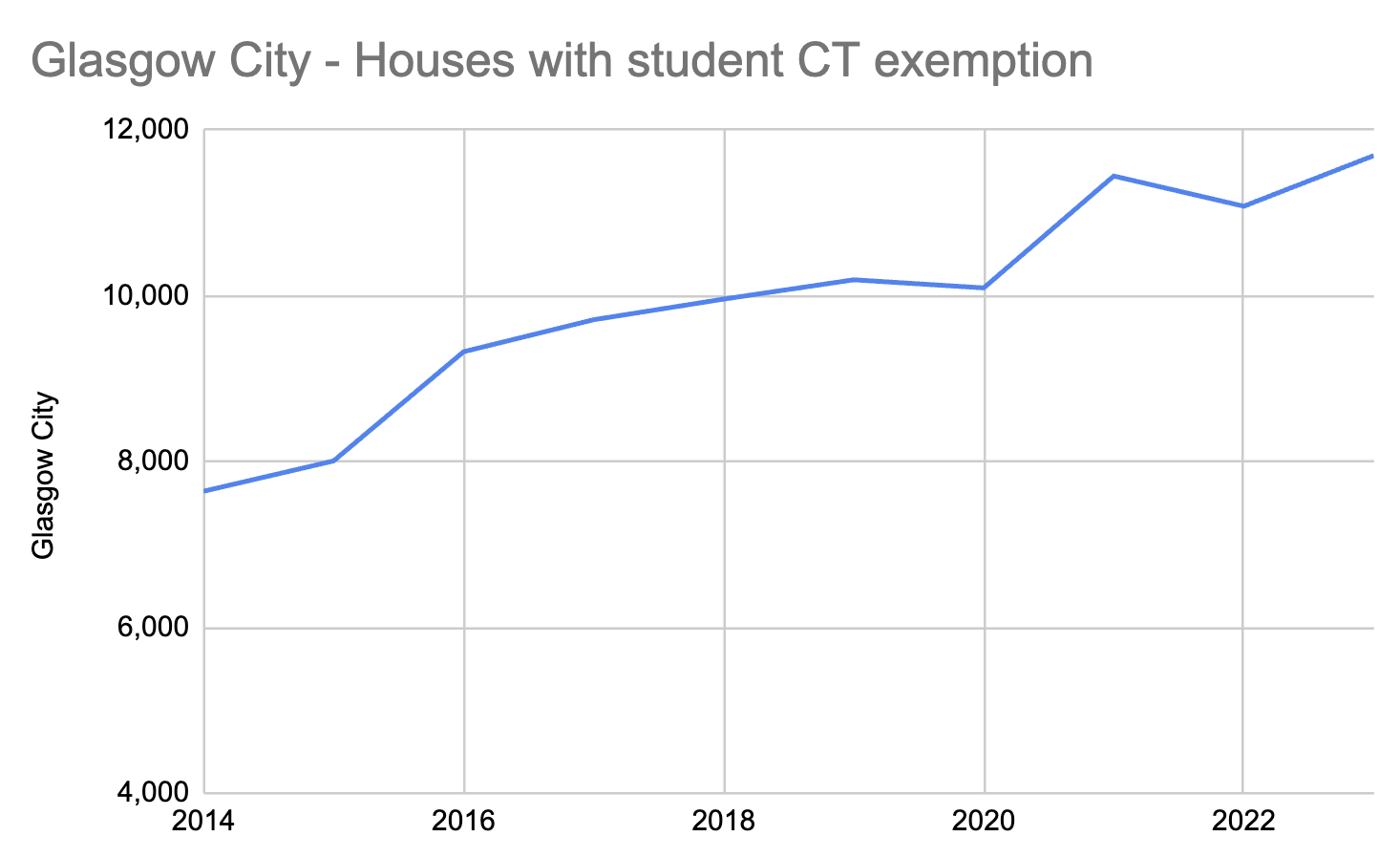

Here’s crisis-hit Glasgow’s numbers:

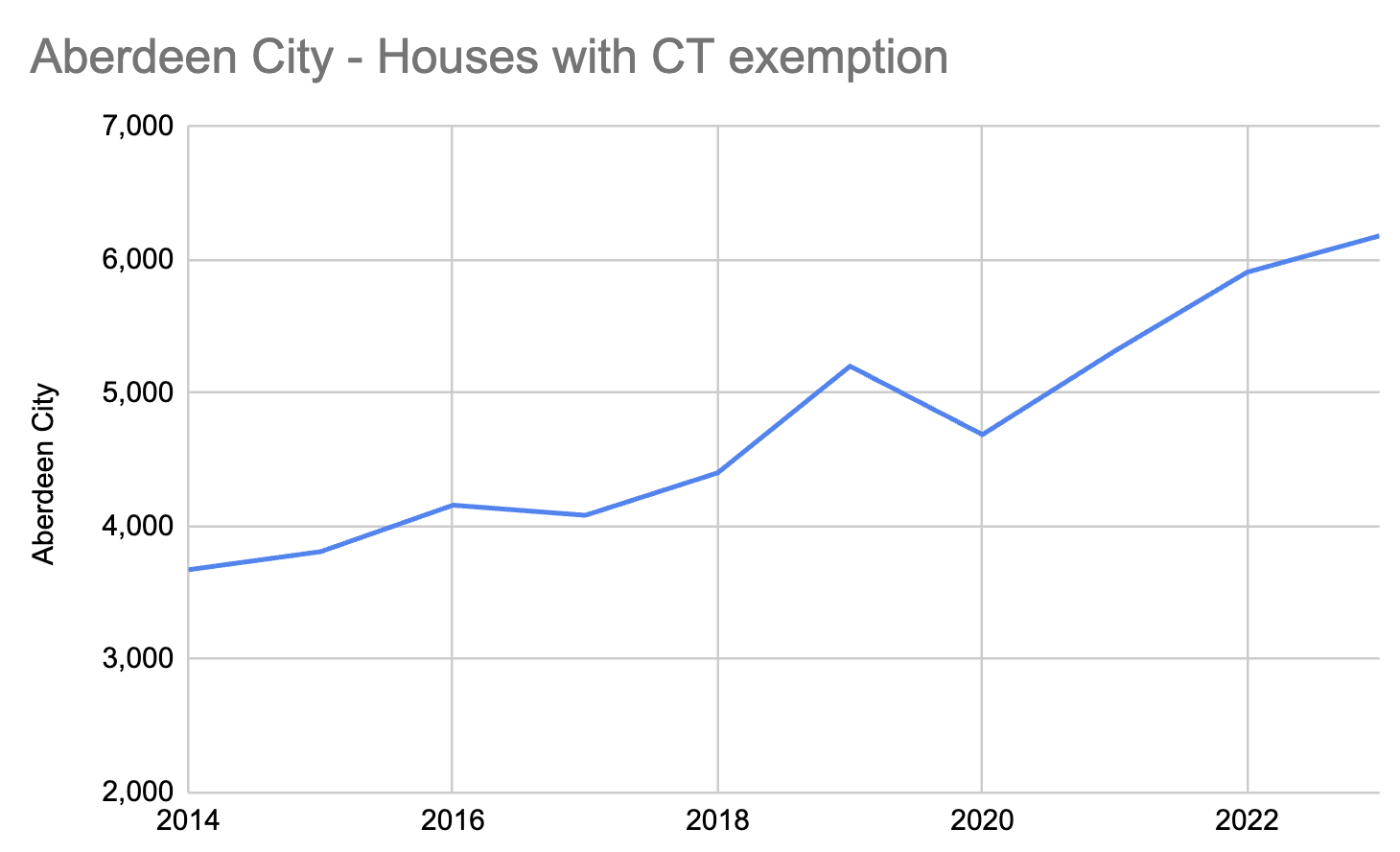

Here’s Aberdeen’s numbers:

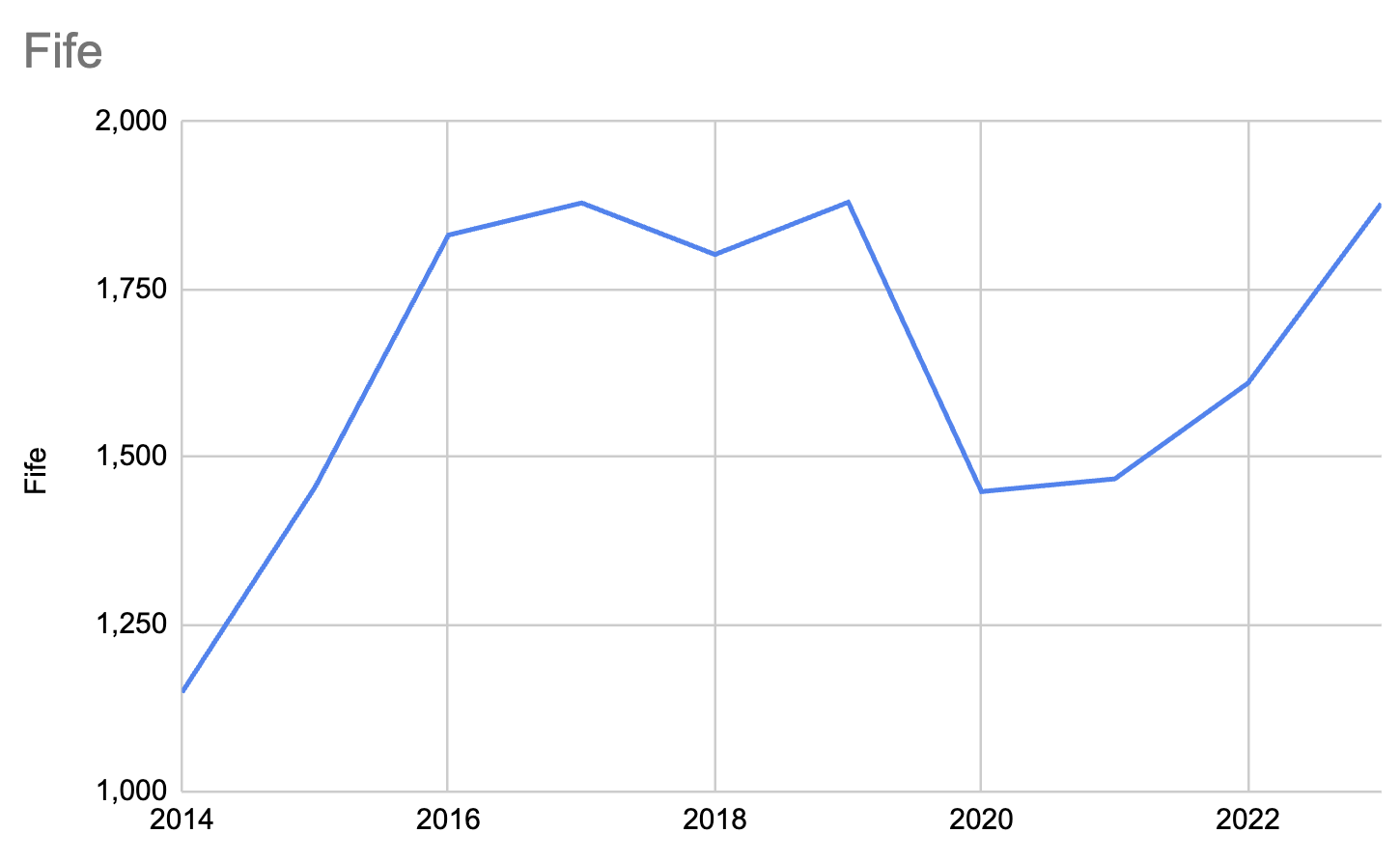

That Unipol evidence also suggests that a “similar shift” has taken place at St Andrews, although the Fife numbers tell a more nuanced story:

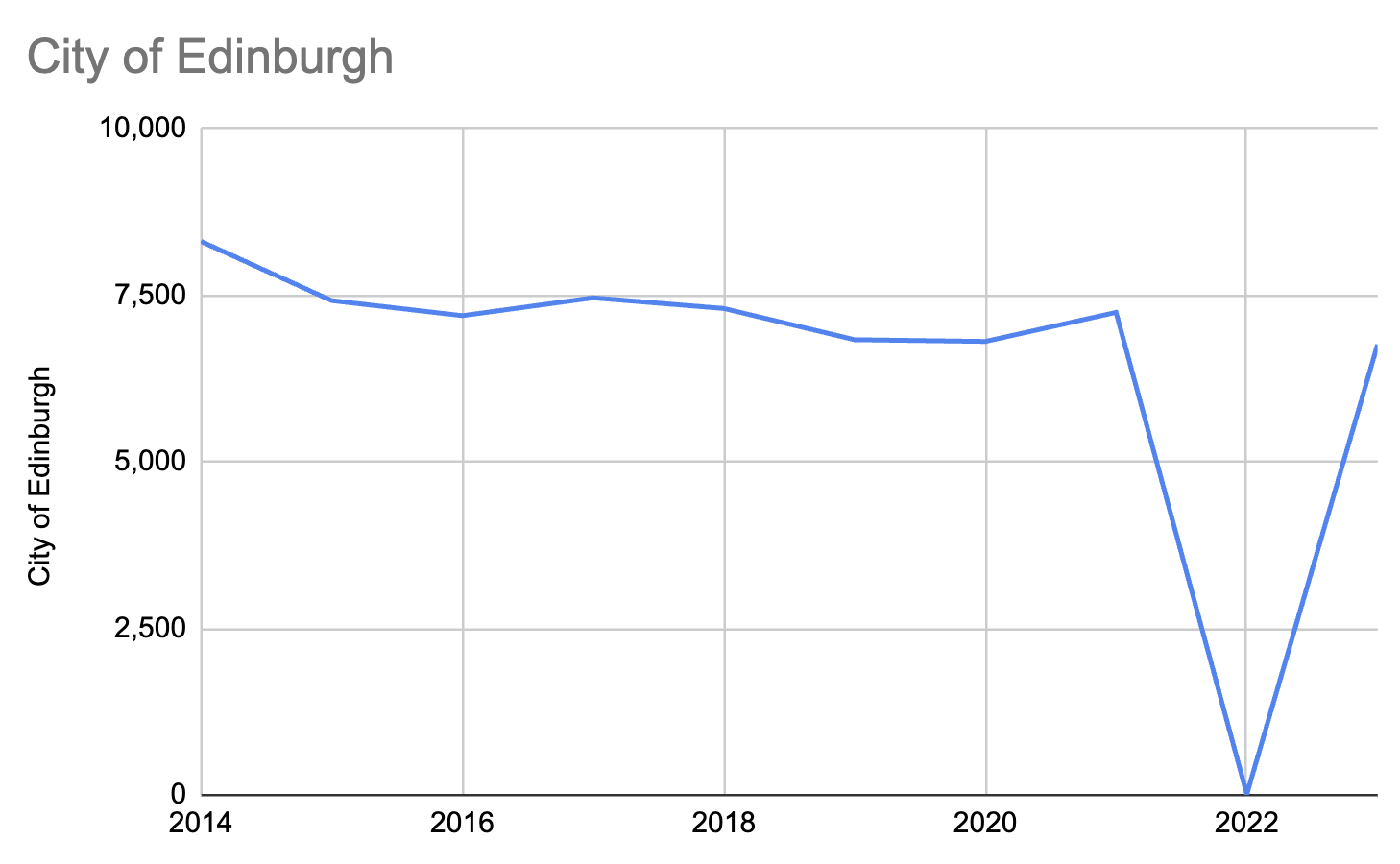

Even in Edinburgh with its “housing emergency”, the numbers are interesting (ignore 2020, the response warned me about data quality in the pandemic year):

What appears to be happening in St Andrews and Edinburgh is as much about a switch towards AirBnB as it is about moving away from student housing – and more generally across Scotland, changes in supply look like pandemic disruption rather than the widespread view that there’s been a “collapse”.

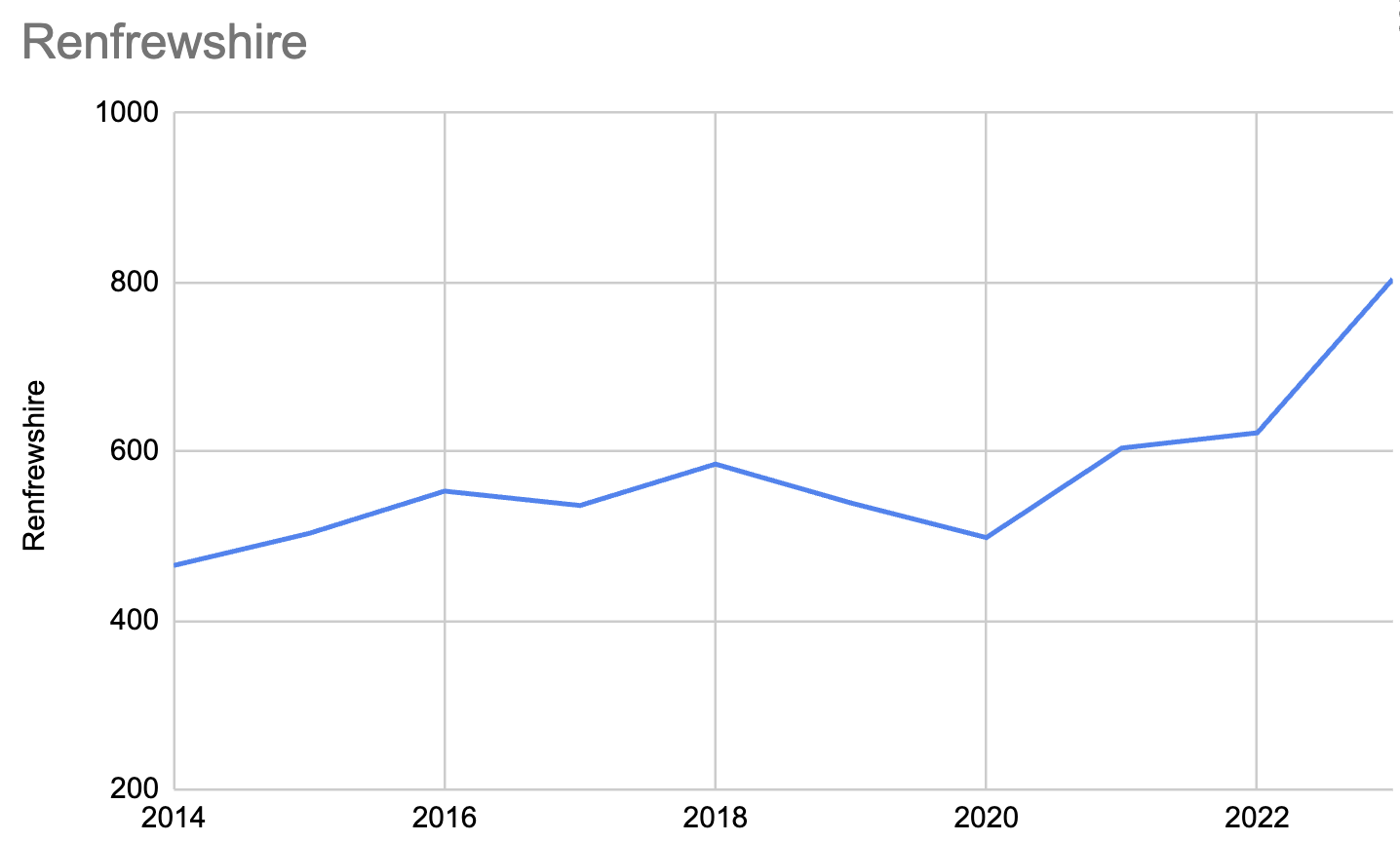

Even in Renfrewshire (home to UWS/Paisley) the story is the same:

Of course we don’t know how many bed spaces we’re looking at here, and I guess it’s possible (though unlikely) that each of the key student cities has seen landlords switch to properties with fewer rooms.

More likely is a mix of factors – some landlords getting out, some entering the market, some switching to AirBnB at the end of the pandemic. And crucially, any “crisis” is almost certainly more about demand growing sharply than supply via the international PGT boom, as I looked at in detail here.

This matters, because even Universities UK seems prepared to trade away better rights for students on the basis of shaky evidence that doing so would hit supply. I’m yet to see real evidence that that’s true.