Did students lose out on learning during lockdown?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

That’s one of the interesting findings on higher education students contained in Generation Covid and Social Mobility: Evidence and Policy, research that dominated Panorama on Monday night.

What we’ve got here are new findings from the LSE/Centre for Economic Performance Social Mobility Survey that was undertaken in September and October, with a particular focus placed on work and education inequalities of what it calls the “Covid generation”.

The labour market findings stole the headlines when the report came out on Monday. 16-25 year olds were over twice as likely as older employees to have suffered job loss, with over one in ten losing their job, and just under six in ten seeing their earnings fall.

Coverage also centred on “lost education” amongst school children, with predictable yet dispiriting findings when comparing state and privately educated pupils.

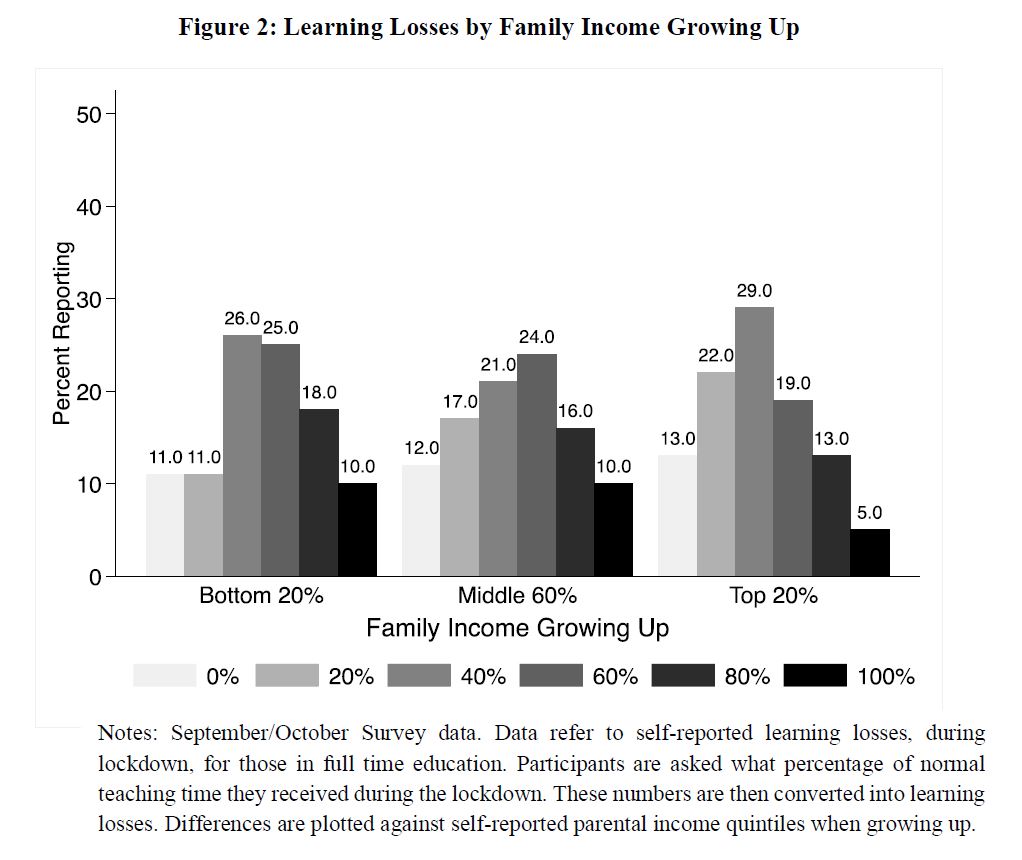

But there’s some fascinating findings on university students. First of all female students were far more likely than males to report that the pandemic had adversely affected their wellbeing – not a huge surprise and broadly consistent with other work on student mental health. But the survey also found that those from the lowest income backgrounds lost 52 percent of their normal teaching hours as a result of lockdown, but that those from the highest income groups suffered a smaller loss of 40 percent – which the authors say reveals a “strong inequality” occurring in higher education.

What could be going on here? Assuming that the sample is sufficiently representative, we are either looking at institutional/course differences or “digital divide” issues. The trouble is that whereas the comparisons are (somewhat) straightforward for full-time pupils, they’re not for full-time students – the number of “teaching hours” in any year differs from course to course, year to year and university to university – and as this survey was about “lockdown” we have whether teaching was even scheduled (and its intensity) given when lockdown kicked in.

Then mix in what we know about the socio-economic make up of different subject areas and different institutions, and you end up with an interesting finding that’s very difficult to see as actionable in any way. Again, it’s interesting that 35 percent of those from the top fifth of the family income distribution report 0-20 percent falls in teaching time as compared with 29 percent from middle income backgrounds, and only 22 percent from the bottom fifth of the income distribution – but given the complexity that this belies it’s not clear what we should or could do about it.

The problem is compounded in some of the report’s analysis – there’s a section that blithely “converts” teaching time estimates into percentage falls in learning and the report repeatedly then refers to “learning losses” – if only it was that simple.

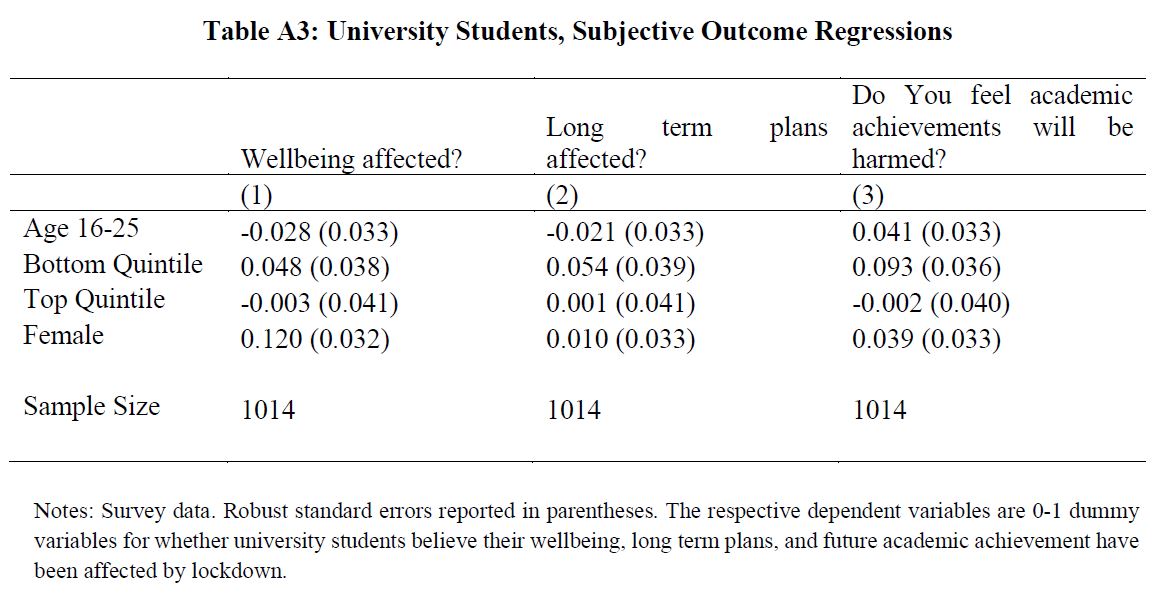

We’re on firmer ground when the report turns its attention to wellbeing, long term plans and prospective academic achievements – this table looks at how these variables differ across gender, age, and family background.

63 percent state that their wellbeing has been affected, 62 percent state their long-term plans have been affected, and 68 percent believe that their future educational achievement will be affected by the pandemic. There is little difference across family backgrounds on long term plans and wellbeing – but there is a striking difference in the likelihood of believing that prospective academic achievement will be affected by lockdown. Students from the bottom quintile of household incomes are 9 percentage points more likely than their peers to believe that their future grades will be changed as a result of the pandemic.

That certainly feels more actionable in terms of targeting support – and is exactly what (at least in England) student premium funding is designed for. The problem is that the government thinks it’s for a lot of other things – including relieving the financial problems of lost employment.