A fees increase is “unpalatable”

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

She said that that was partly because she knows that lots of students across the country are already facing big challenges:

…around the cost of living, housing costs, lots of students I speak to who are already working lots of jobs, extra hours, in order to pay for their studies.

Sadly she wasn’t referring to the tuition fees increases that international students and postgraduate students face – or she’d be introducing measures to tackle their unpalatability too.

She was referring to the undergraduate tuition fees cap. Fear of debt is real – although I’m guessing that the difference between, say, £9,250 and £9,750 is fairly miniscule when compared to the difference between £9,250 and £0.

And unless something is done on maintenance, that cost of living, housing costs, working lots of jobs, extra hours thing is only going to get worse.

Meanwhile for those who’ve paid private school fees to get their kids into the Russell Group and who pay their kids’ frees upfront, the ongoing freeze is deliciously palatable, thanks very much.

A VAT increase here, a university fees freeze there. The government taketh away and giveth.

What’s curious in that “we need to worry about students and their income” framing is that it’s about the reality of the student experience rather than the debt after it.

And the level of the maximum fee has almost nothing to do with the cost of living, housing costs, working lots of jobs, extra hours thing.

This is an old trick that the previous government would pull with regularity – so for example, in January 2023, under the headline “Cost of living boost for students”, universities minister Robert Halfon said:

Maximum fees will also be frozen for the 2024-25 academic year to deliver better value for students and to keep the cost of higher education down.

So it’s not students while on their programme that would be impacted by a fees rise. If not them, which graduates?

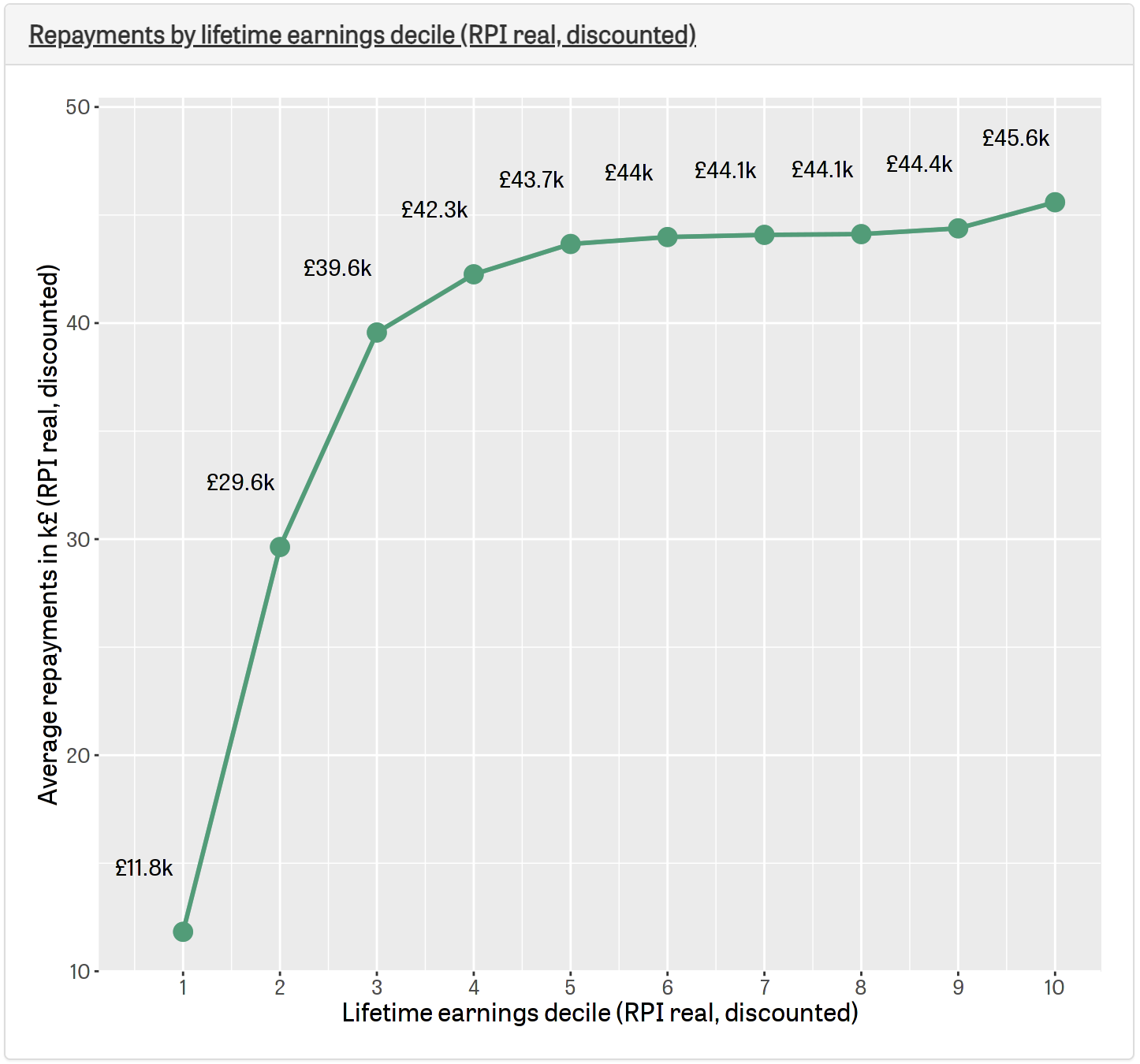

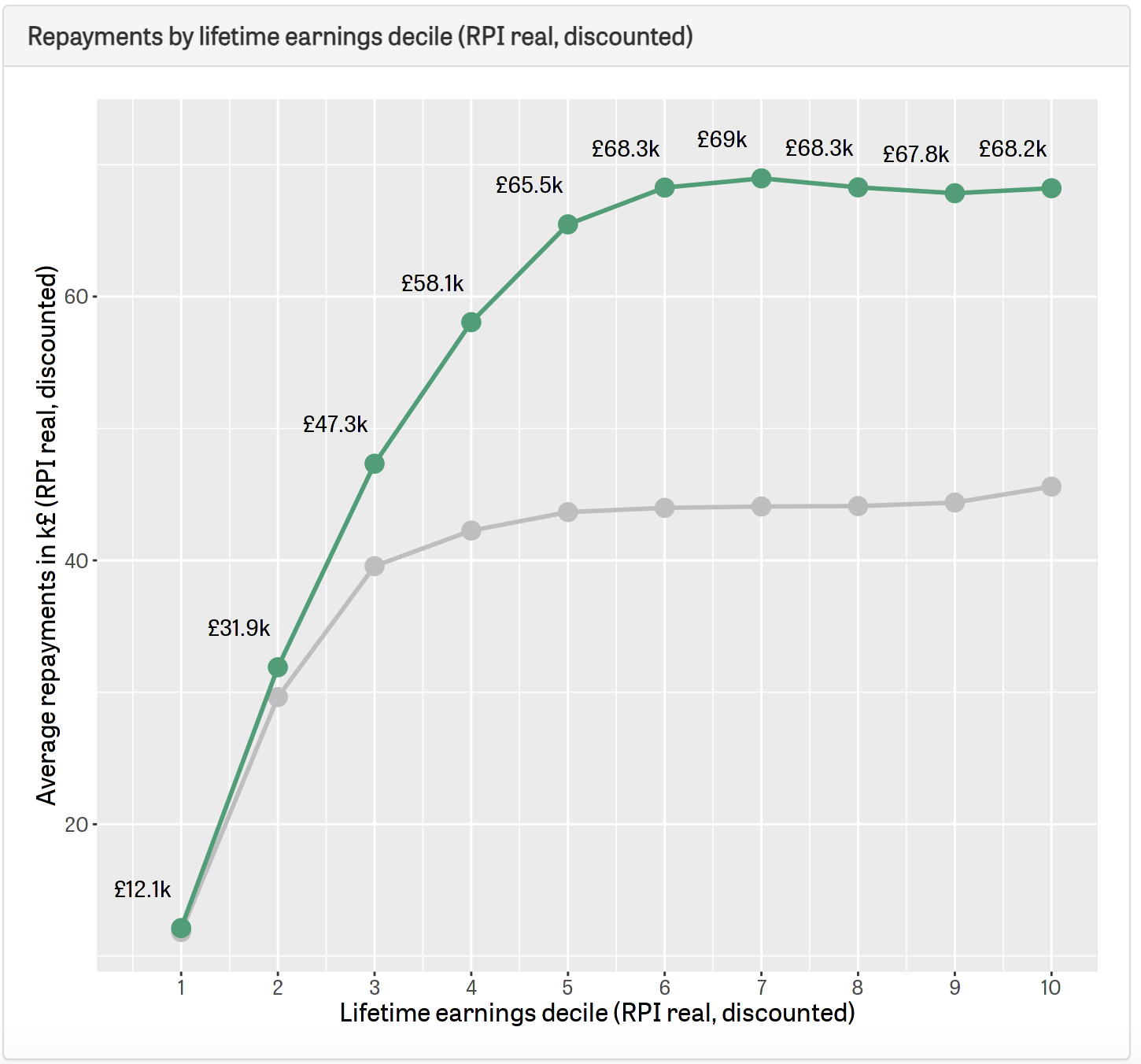

The IFS loans calculator shows us the profile by lifetime earnings decide of who pays what:

That flattening is the result of a 40 year term before the loan is written off, and a lower-than-it-used-to-be repayment threshold.

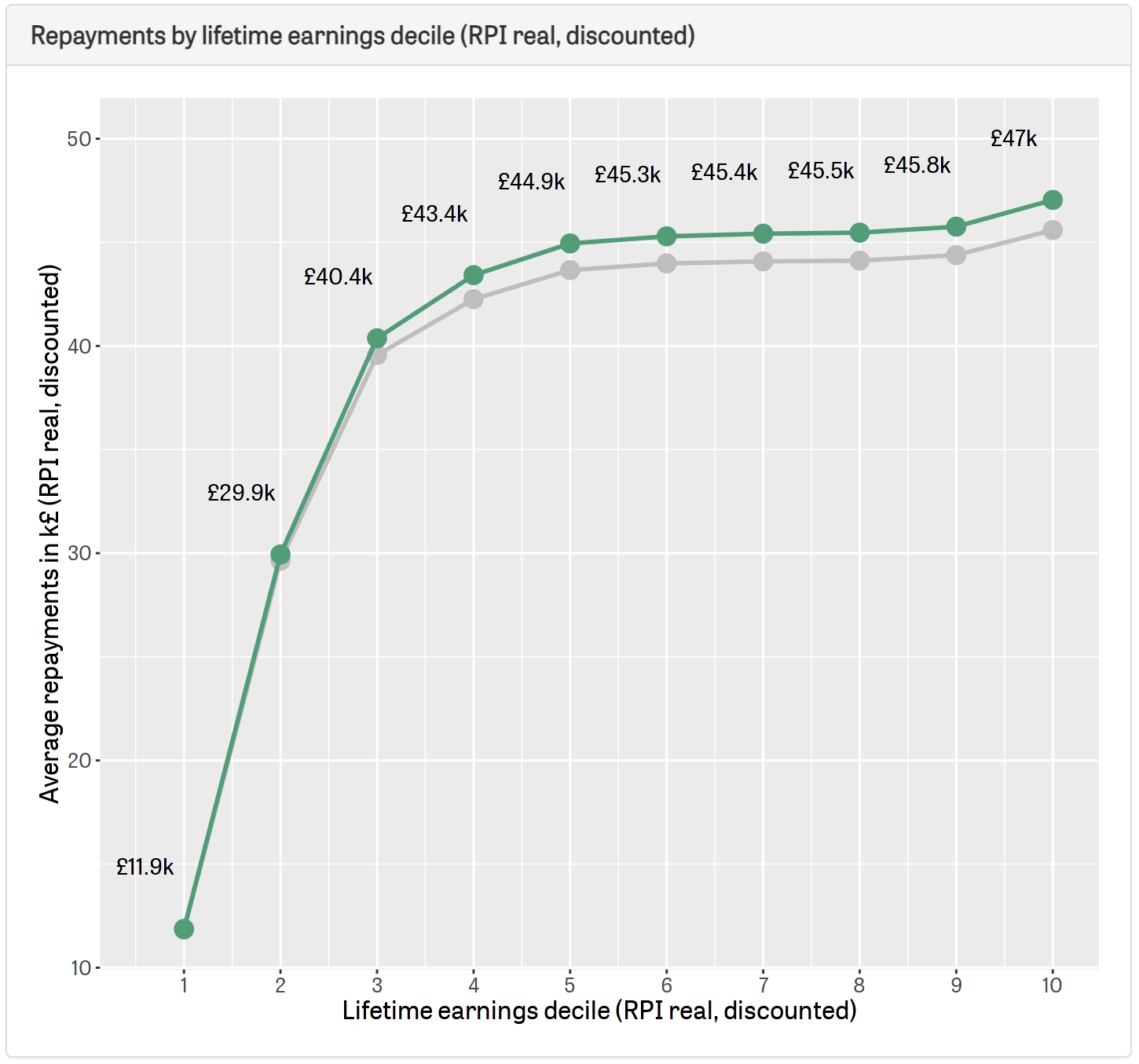

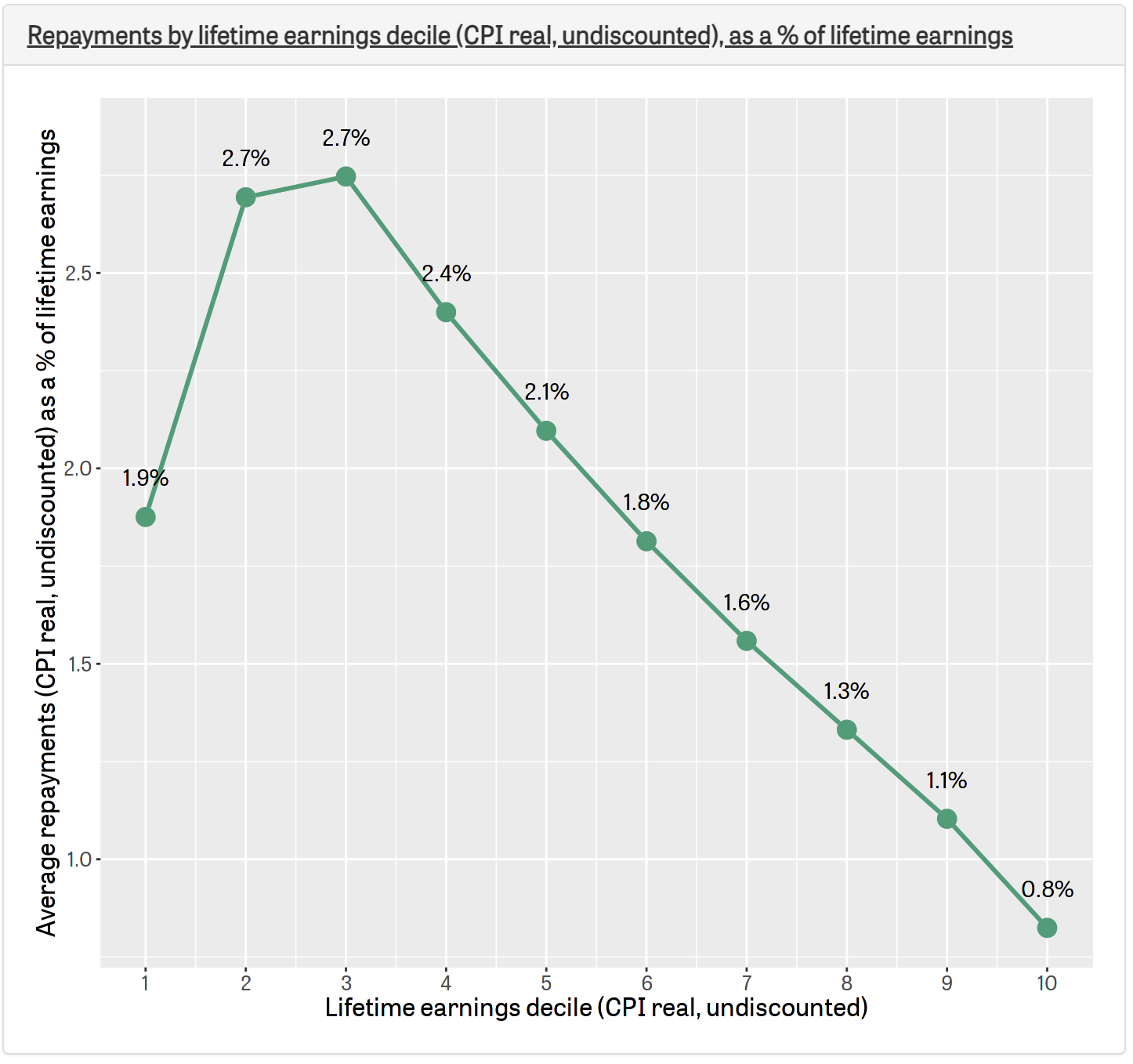

If fees were to increase to £9,750, the curve would look like this:

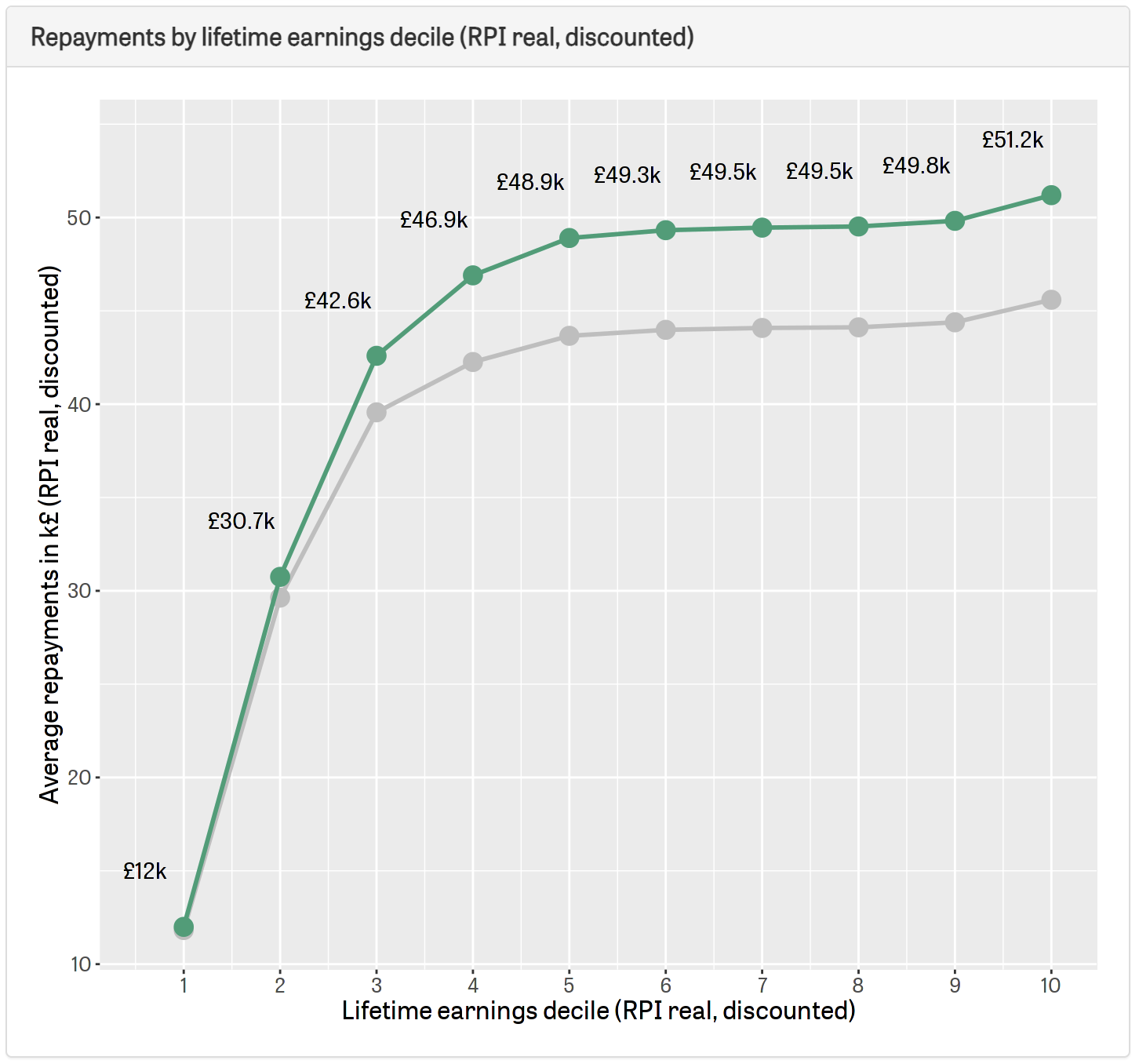

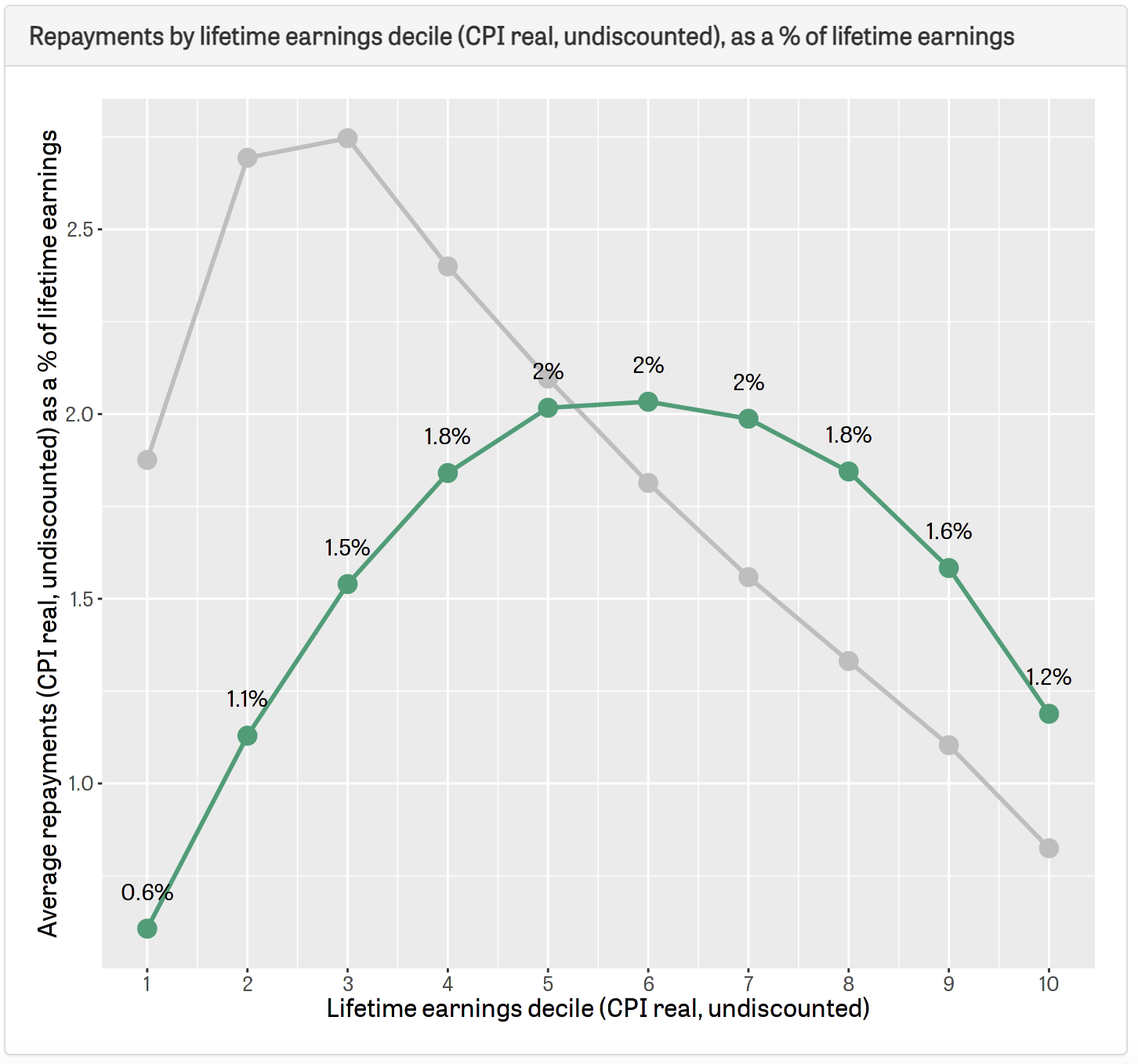

And if fees were, say, £11,000, it would look like this:

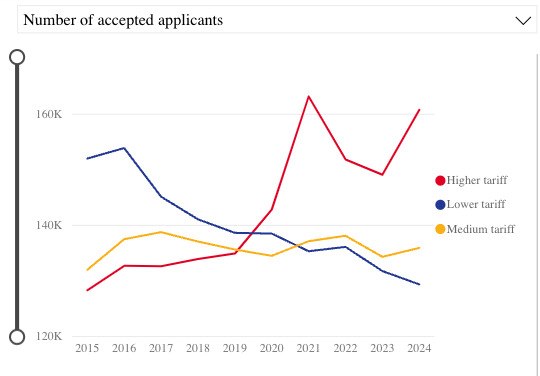

Arguably, the thing that would make the most difference to students would be to take steps to introduce some distribution controls to student numbers such that Russell Group students weren’t packed into providers in cities where rents are rocketing, and those in low tariff providers aren’t having to assume that their course will be restructured as those providers fight to survive:

But maybe the bigger question is whether students would be prepared to trade off more debt on both the maintenance side and the fees side. Here’s what the curve would look like on a £9,750 fee and a similarly modest £500 bump on the maximum maintenance loan:

That, by the way, would result in a negative RAB of -14% – in other words, in the long run, the government would profit by 14p off the back of every pound loaned, rather than putting in any subsidy at all.

Rather than just looking at the amounts, we could look at the proportion of lifetime earnings that all of the above represent. Here’s the current curve:

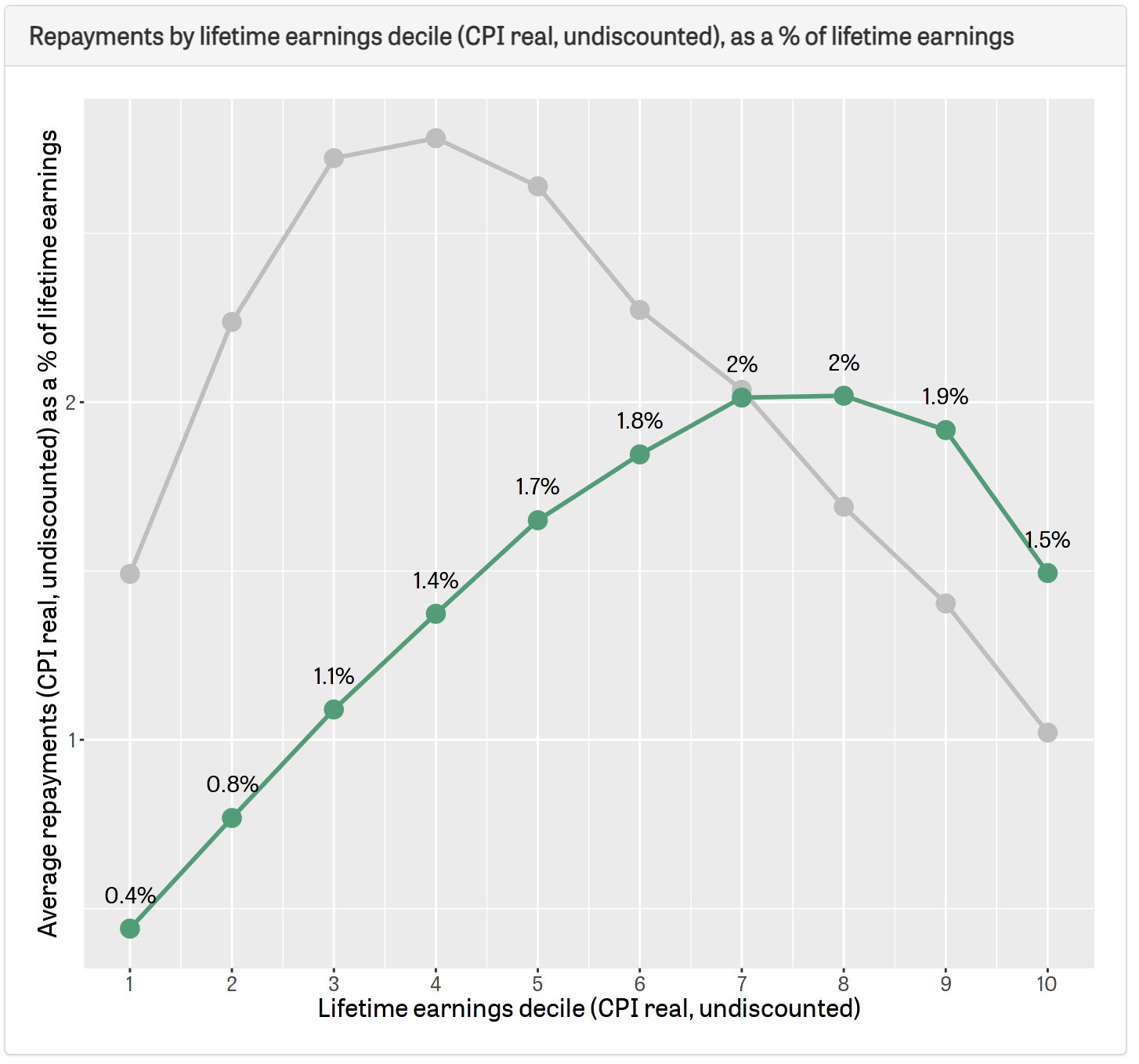

And here’s what it would look like with a bump in fees and maintenance, a 30 year term, getting rid of the interest rates bung and a 12.3k rise in the repayment threshold to cushio hard up grads in their 20s and early 30s:

And here’s the difference for women:

That, by the way, would result in a RAB of 10 per cent, and a total long-run government cost per cohort (discounted, RPI real) of £3.8bn – which is exactly the same as the total long-run government cost per cohort now.

In other words, starving universities and students of resources now is a result of keeping the long-run costs of HE low for the top half of earners rather than the bottom half. That feels fairly unpalatable to me.

Stellar stuff Jim – although I’m not sure prospective students would necessarily be thinking about how their course at a “low tariff provider” might be restructured. I doubt it’s on their radar much at all (happy to be wrong though, and arguably a political activation of the prospective “customer” would be welcome). Clearly the current system could be made both more progressive in terms of who ends up paying what and what the cost is to government. Do you think a moderate fee increase would really have impact on access? Everyone assumed the increase to £3k then £9k would, but… Read more »

Jim does this mean I can put you down as in support of a system of student distribution?

Cant’ speak for the rest of the team but always have been always will be