2022 broke the student housing market. Here’s how to avoid a repeat

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

Notwithstanding that the figures need to be taken with a dose of salt – the categories are a bit shaky and it’s not especially clear when students respond – we do get a sense of how things have been changing.

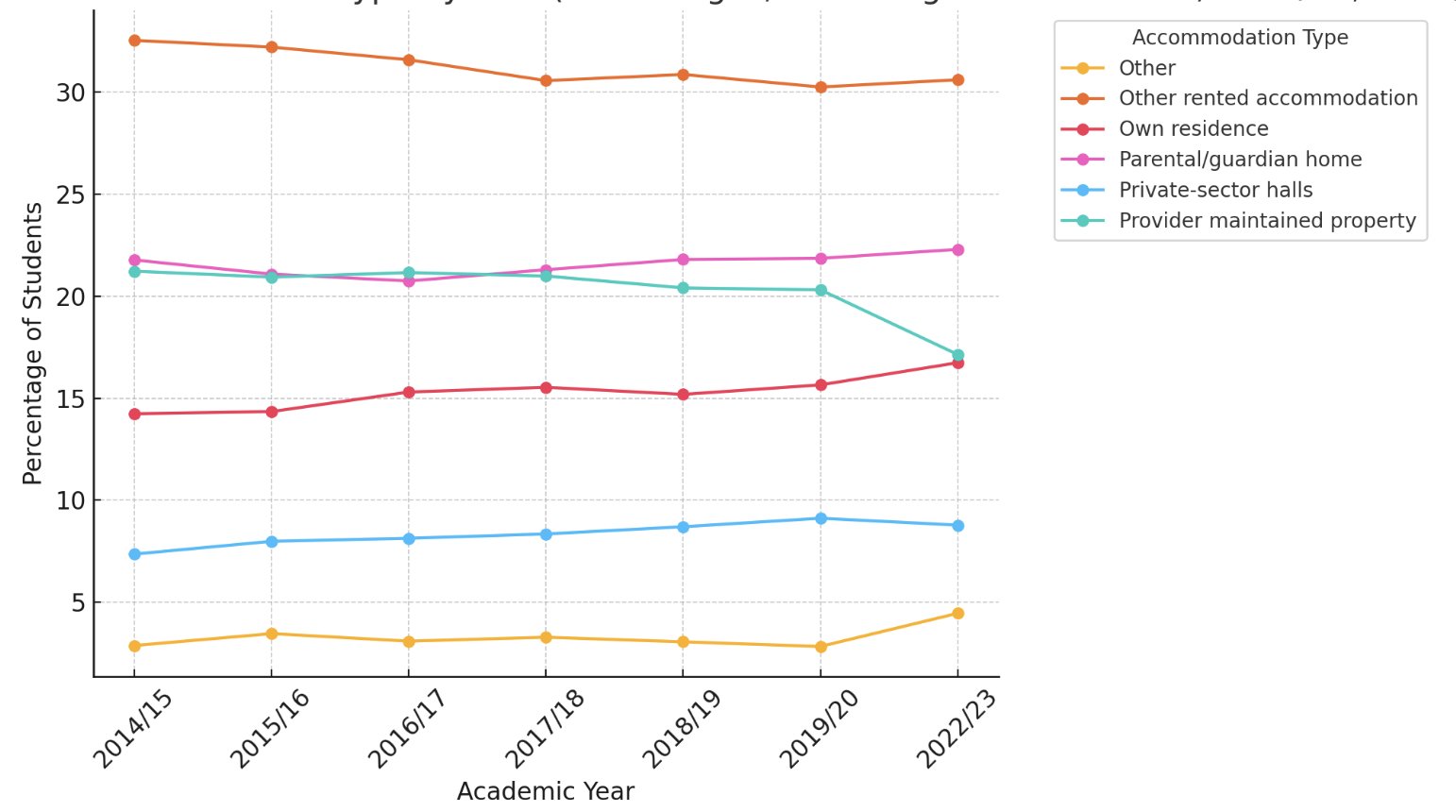

First, first degree undergrads. If we remove the pandemic noise of 2020/21 and 2021/22, the interesting thing in this graph is the sharpish drop in undergrads living in university halls:

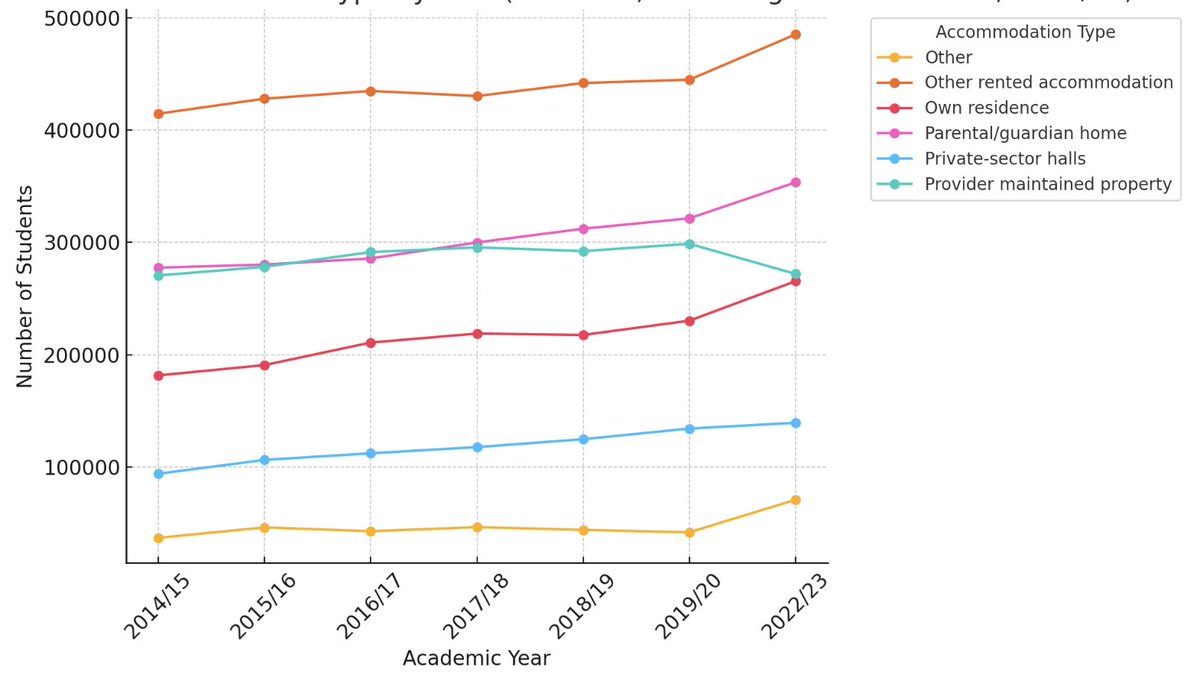

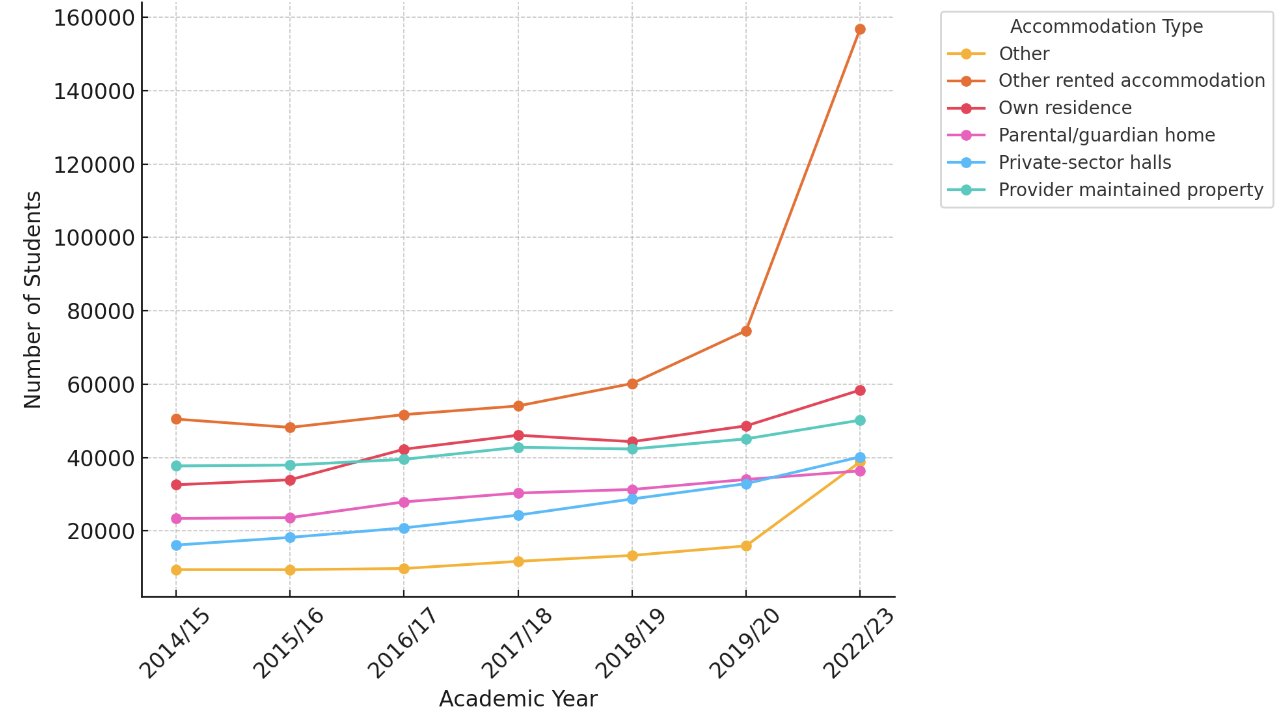

That’s percentages. Here’s the same chart in raw numbers terms. Again, we see a sharp drop in university halls housing FD UGs:

Why might that be? Some of it is students (choosing?) to live at home, but if you look at the raw numbers chart, there’s just as big a rise in UG FD students in “own” and the two “other” categories – usually houses.

Why might students be “opting” to live in houses rather than halls? Let’s zero in a bit on “entrants” – FD UG entrants.

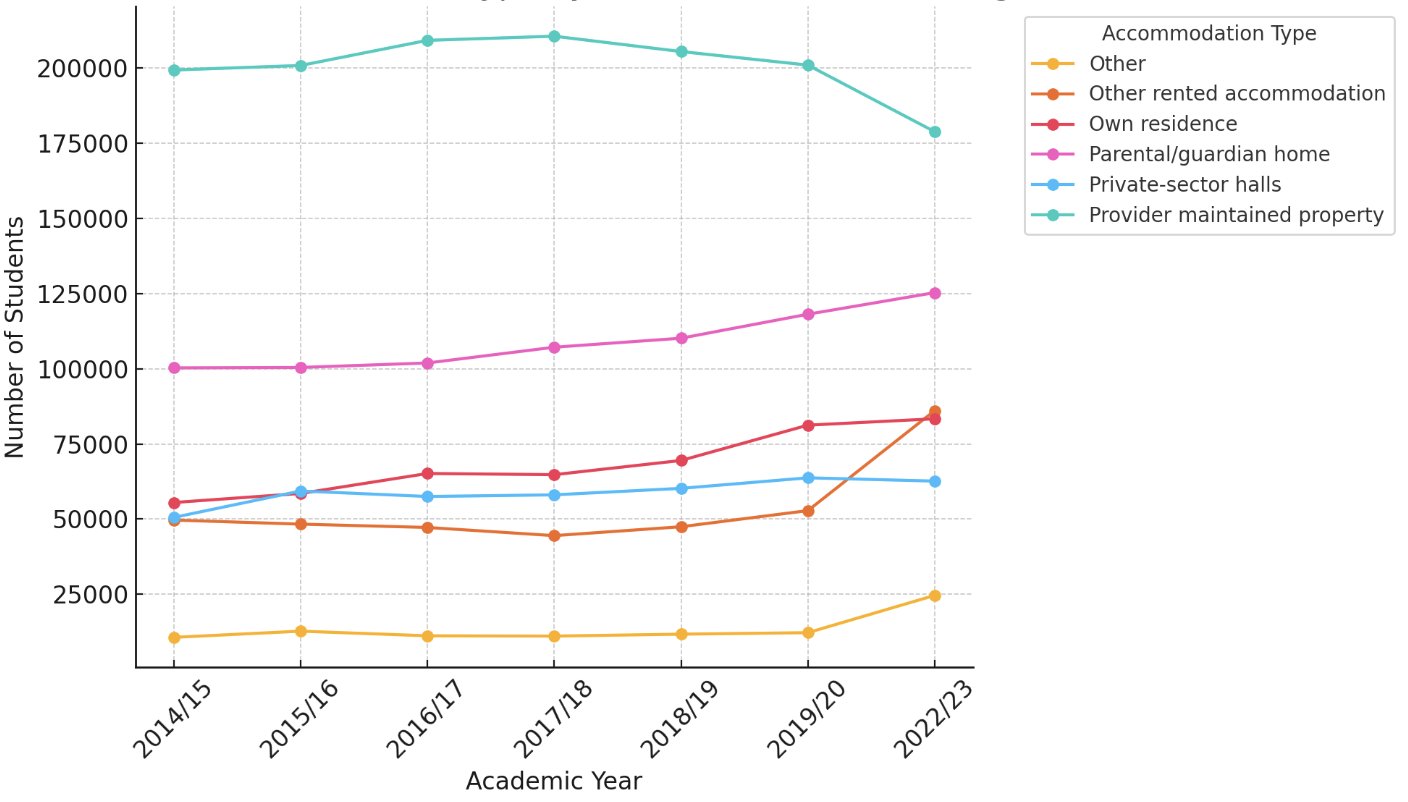

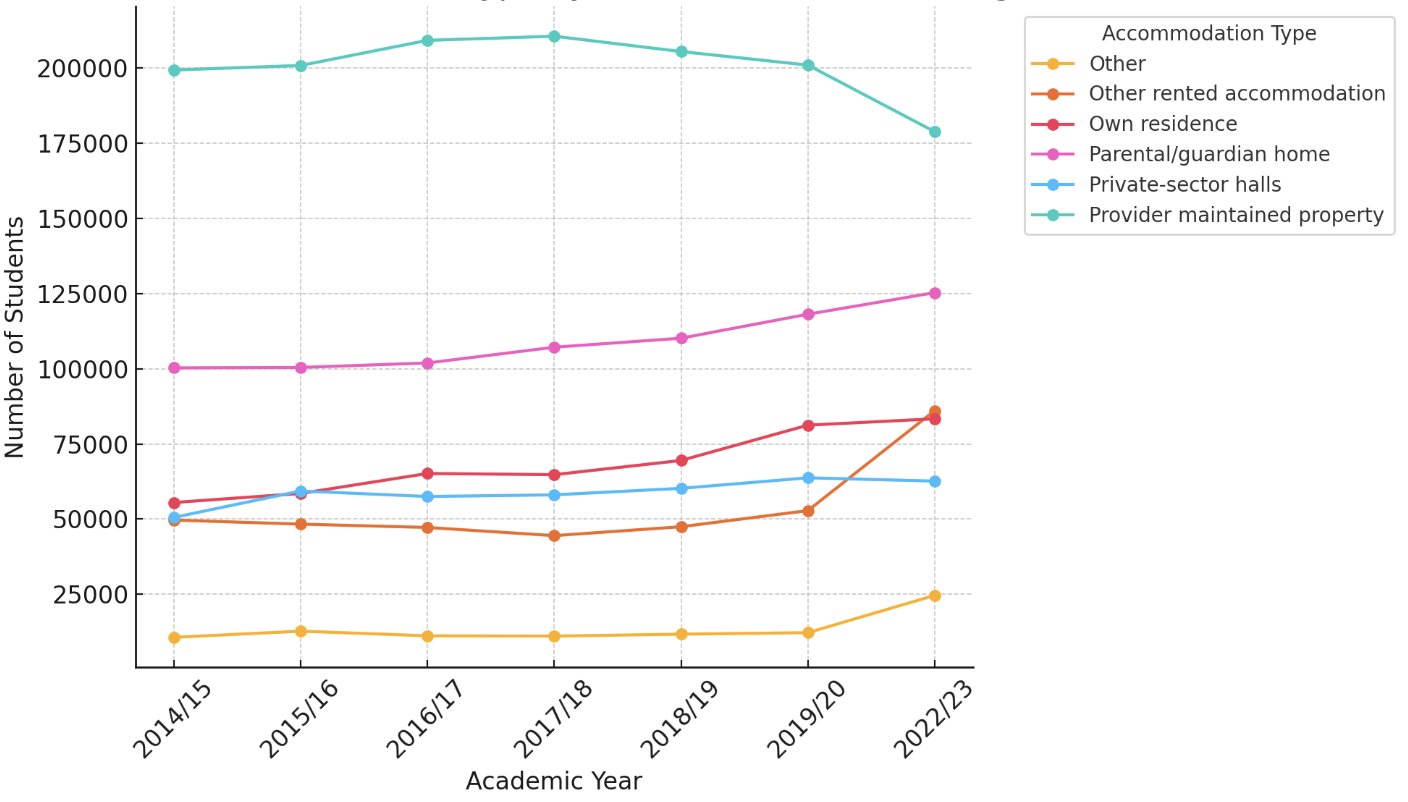

Here’s numbers – again a moderate rise in living with parents, but a sharpish rise in 1st year UGs in HMOs and houses, and a sharpish drop in those in halls:

Are they being priced out of the university halls experience? There’s no drop off in 1st years living in private halls – the drop off is in university halls. Maybe it’s price. I doubt it’s choice. Maybe it’s who gets allocated into halls.

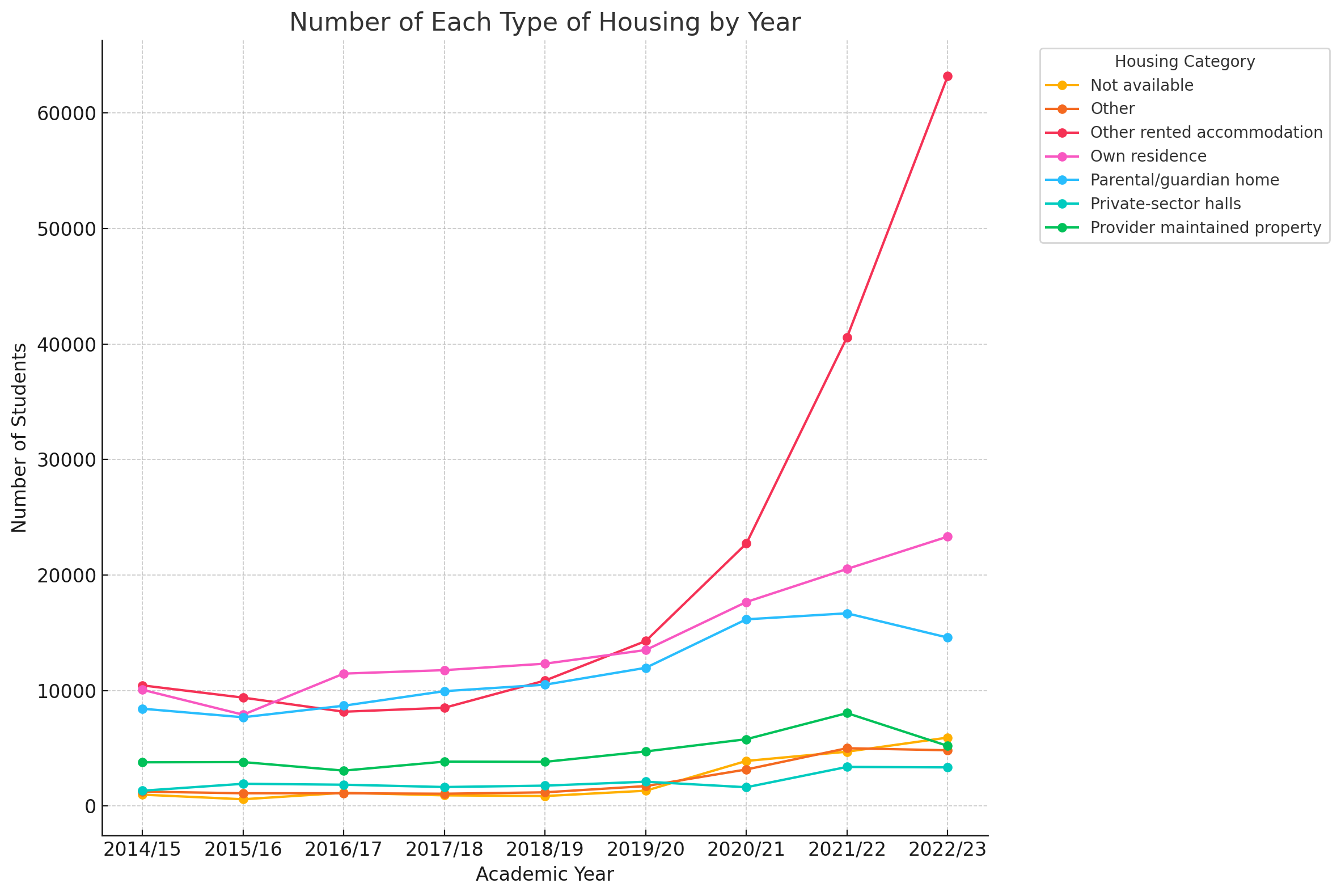

Here’s 1st year or single year PGTs. This chart reminds us that the sector blithely and irresponsibly recruited a huge number of students in 2022 and, frankly, had no scooby where they’d live. This chart excludes the high number of “unknowns” too:

What the chart also implies is the cause of student rents in the private rented sector rocketing. As universities moved to cover their losses on inflation via international PGT recruitment, said recruitment will have shoved up demand way beyond what the market could bear in most university cities.

That will have had two impacts. For housing close to campus, higher rents – often pushing up the price of housing for others in the city. Remember that the sort families that were on £25,000 a year back in 2007 these days have to find £4,000 a year in parental “contribution” – and that’s without this aspect of inflation.

So for lots of students, it means living much further out in areas not well served by traditional student bus routes – along with much higher rent costs than many international students will have been budgeting for.

If it was up to me we’d triple the number of international students if we could. But only if there’s somewhere affordable, safe, suitable and of reasonable distance from campus to live.

Recruiting beyond that capacity in 2022 might have plugged university budget holes, but it almost certainly created and widened those budget holes for those living away from home and those at home whose families rent.

For England, MPs have an opportunity in the Renter’s Rights Bill to amend the Higher Education and Research Act to give OfS the kind of powers over information on student rents that the Augar review mandated. They could also make Universities UK’s guidance on accommodation planning a duty not an option, and give local planners more coordination power in this area.

The alternative is to trust universities to not recruit beyond the capacity of their housing markets next time they can, and to imagine that the market will magically provide bed spaces at a sensible cost, with clear information for students whose families in some cases will be predicting the rent costs their kids will face four or five years out.

Me neither.

It’s also worth remembering that the rent provisions that are in the Bill – once a year max rent increases, and tenants taking landlords to tribunal if those rents are above market rates – literally don’t work in a Bill that also empowers landlords to evict students in June, July, August or September.

It will also mean they can rent a house to a group of desperate international students in January, and threaten to evict them in the middle of the summer if they don’t pay a wedge more rent. Not that anyone in Whitehall has noticed that some students start in January, or need to stay on in the summer.

Those controls should apply to houses, not tenancies – and if landlords must be given the chance to evict, the power should kick in in a way that’s aligned with a student (or group of students’) academic year and needs, not some fixed calendar point.

Oh – and to return to the first question, the drop in UGs in university halls was pretty much matched by the rise in PGTs in 2022. That may well be some providers having a dearth of domestic students living away from home these days as those away from homers cluster into providers further up the tables. I suppose the bleak calculation was that at least some of the PGTs piling in to cover the losses could afford to pay.

One other bonus chart – which seems to explain the anecdote that some universities struggled to persuade international PGTs to fill their halls even as numbers shot up. This is universities that became universities in 1992 – and reminds us that good accommodation planning is about price as well as bedspace volume:

The sector ruthlessly pushed the externality of over-recruiting PGT ISs onto the local communities that in most cases already had housing under-provision – same story in Canada and Australia. Hence there as here the political backlash is visa reductions – combined with currency problems in Nigeria – leading to a sudden drop in IS PGT recruitment (while UK UG recruitment at some Us is hit by their over-recruitment at the Russellers). Thus, we are seeing a sector-wide reset to student numbers prior to recent reckless expansion – not quite the end of the world, nor necessarily leading to the insolvencies… Read more »