In case you missed it, there was a fascinating piece in the Guardian the other day about “nostalgia memes”, which people (principally on Facebook) create and exchange to idealise the past. Who remembers “proper binmen”?

I come across a lot of an equivalent in higher education circles when people talk about the environment of academia and the student experience. And I’m sure I’ve encountered a whole range of them while watching the deliberations surrounding the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill.

There’s a strange mix in both the images on Facebook and in the examples that people use to evaluate and imagine university life.

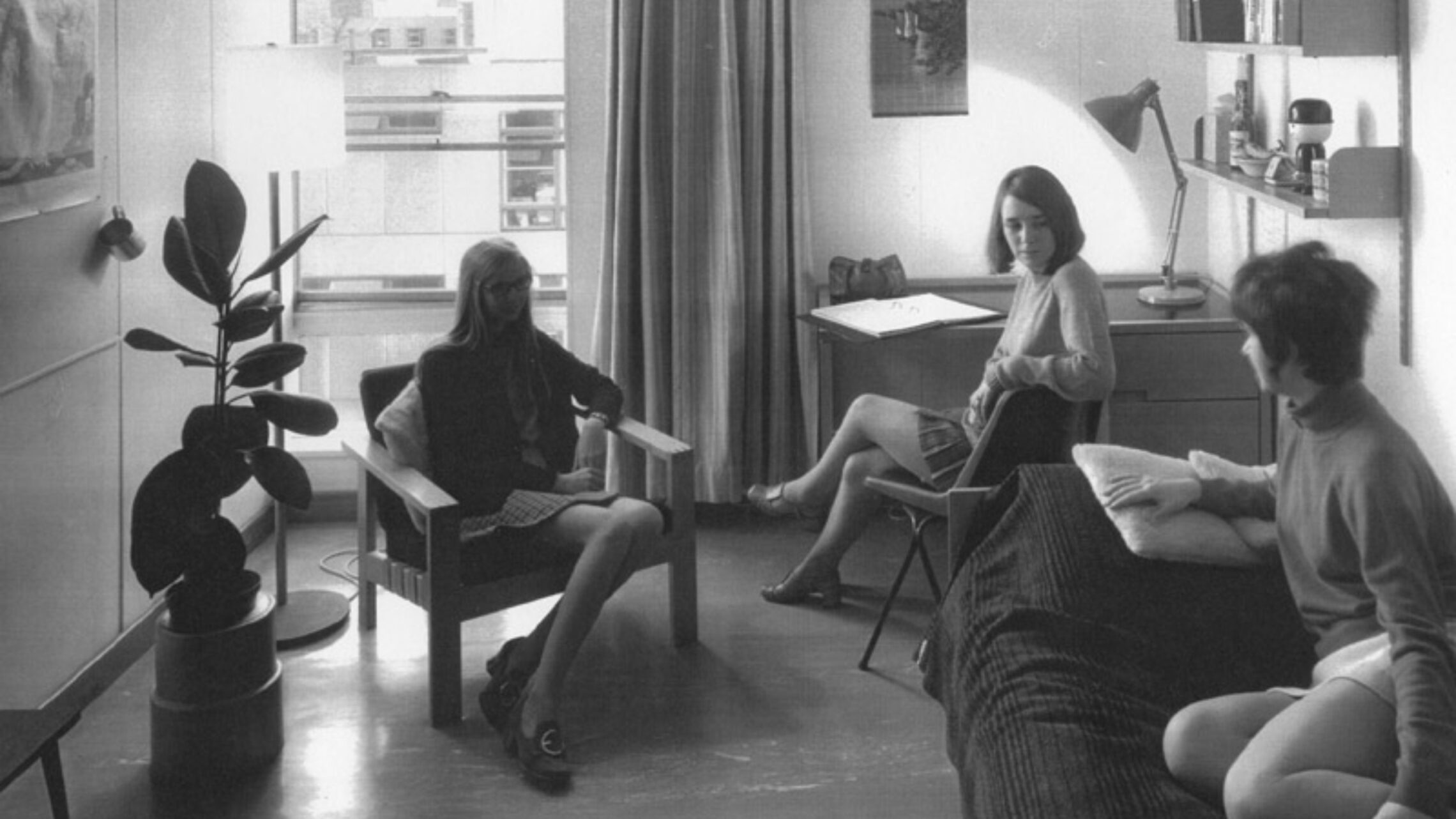

One tendency is to hark back to some golden age, when a full-time student was a full-time student, when class sizes were small, when students were more united (and homogenous), when students got grants and graduates got guaranteed jobs. The way in which opportunity was so heavily restricted, and some of the darker aspects of the treatment of students, are rarely mentioned in those retellings.

The other is a kind of survivor bias – the “never did me any harm” of not having central heating or a toilet indoors, translated into being students sleeping with professors, living with mould in a bedsit, or accepting that feedback might be a few weeks late while a lecturer returns from sabbatical. If we don’t make it tough, as it was in my day, how will students gain the skill of resilience?

Much of this amounts to intergenerational banter, but sometimes the question that comes up is whether the past is lost and to be forgotten or to be fought for in some way.

Take that notion of the fully-immersed “full-time” student with no other responsibilities to burden them. Is that idea gone forever in a mass system, requiring us to adapt to the contemporary realities of student life – or is it to be fought for (and the normalisation of a busy and burdened student to be opposed) if we are to cherish the idea of more not meaning less?

I threw a wish in the well

I was thinking about this when reading the coroner’s prevention of future deaths report in the case of Harry Armstrong Evans, a University of Exeter student who died by suicide in June 2021. The coverage of the case highlighted one of the recommendations on personal contact – whether pastoral tutors should offer to exchange mobile numbers with their students – and generated quite a significant reaction from academics.

I don’t need to explain here why I think that approach would be problematic for all the reasons that have been given previously when this kind of suggestion has been made in the past. I might also add that it remains my view that universities are unfairly being asked to do what the NHS should be doing. That said, contrary to some commentary, for me, there clearly is a role for mental health training insofar as it impacts on providing effective personal academic support, and there are clearly lots of aspects of teaching and learning that ought to be seen by professionals through a mental health lens.

But what I do want to reflect on is one of the comments underneath this interview with Evelyn Welch, the newly in post vice-chancellor at the University of Bristol:

I don’t think she has made the connection between student unhappiness at Bristol and the continued rapid expansion/growth of the university, with its flashy building projects and colonisation of vast swathes of the city centre. It’s the classic tale of many Russell Group universities. Staffing and human resourcing haven’t kept up with the vigorous pursuit of student numbers. Tutors get stretched, classes get bigger, welfare support is inadequate and there just isn’t enough to go around. The system becomes impersonal and students get “lost” and their needs go unnoticed in the vast new university, and become more vulnerable.

Is the idea of the smaller, more personal, and less stretched university a kind of nostalgia meme, possible only in Oxbridge? Or is there something important in the conversion of the university from village to town to city that is helping to exacerbate what is now a long-term crisis in student self-reported mental health?

And crucially, when we ask ourselves who should provide a professional individualised crisis service or how that should be delivered, do we miss an important decline in what I tend to call “horizontal” support rather than “vertical”?

Don’t ask me; I’ll never tell

Pre-pandemic, in the loneliness research we carried out back in 2019, 6 per cent of students specifically disagreed with the statement, “if I needed help, there are people who would be there for me”.

Students that lived further away, those with more responsibilities, those spending less time together in student groups and those that were more anxious were less likely to respond positively to that question. And then we know what happened during the pandemic.

In many ways, the basic model of higher education assumes that students become “adults” at 18 and can then be left alone. But maybe that was possible in the kind of contexts of class (and class sizes) that were in the past. What about in today’s context of hyperdiversity and “middle stage” of adulthood?

Perhaps it is reasonable to surmise that a model where a huge proportion of students are away from home but that hasn’t been able to scale the community intimacy and immersion assumed in the boarding school model carries significant risks – many of which are about “noticing”.

I looked to you as it fell

What you then do about that is interesting. Building belonging and community at programme level, for example, becomes a safety concern as much as it is a pedagogical issue.

One of the threads that links conclusions in the Abrahart case and the Harry Armstrong Evans recommendations is a reach by the judge for “someone” to notice and act when a student is struggling. As such, imagining that university is as it was back then, I can see why they reach for the personal tutor – however unsuitable in the modern context.

I should say that while the traditional personal tutor model (whatever that is) is obviously not suitable, I am increasingly attracted to the idea that every student should get a dedicated academic coach. You would need to do major structural work across the rest of academic delivery to pull it off. Still, an actual person who tracks progress, helps a student navigate and generally looks after a student becoming a student ought to be powerful.

If that involves a reduction in other academic delivery costs – where bigger lectures and modules or less research pays for academic coaching, then we may need to go there. Wolverhampton’s Academic Coaches scheme and UA92’s personal coaching schemes won’t be the only ones around the sector – but they ought to be considered.

I’m increasingly of the view that students are prepared and able to operate quite sophisticated community networks of support – and often do (and not just in places like Durham) – but that needs some coordination and recognition.

I also think that students having to navigate the busy and complex department store of HE is hard work. Providing “personal shopper” sorts of support and the deliberate development of academic student communities could reduce the tendency for opportunities and support for students right now to resemble a chaotic set of market stalls, run by fiefdoms, that all vie for student attention and budgetary protection.

Ultimately, I have no doubt that the university and SU at Greenwich are right that there was and still is significant power in ringing every student. But if we stop and think about why it’s so powerful and what that says about how we’ve managed otherwise desirable massification, it ought to cause us to view phone banking not as best practice – but as a backstop when all else fails.

I read that comment in the Times as it appeared and absolutely agree about Russel Group student growth and follow on resourcing provision. To provide a direct and personal contact point for each of 32,000 to 50,000 students is an impossibility. Also in the paper, they compared 2 student welfare cases one from a University with an overall SSR (all staff types, so very crude) of 11 to 1 versus an institution with an SSR of 2 to 1, and saying how wonderful the provision was in the smaller institution. Of course it was!

I don’t see any reason in principle why a very large institution shouldn’t retain strong personal staff-student relationships if SSRs remain comparable and the right structures are in place. Probably more damaging than institutional growth per se is the move, in the name of efficiency, towards fewer, larger programmes, the merging of small departments into larger schools, and the tendency to try and get students doing as many admin tasks as possible online. Until a few years ago our students’ first port of call with most practical or pastoral questions was our popular and approachable departmental receptionist, who they all… Read more »

Most American first year students sleep 2 to a bedroom in their dorm room, not because the university or the student lack the resources, but, sensibly, largely as an early warning system flagging up quickly any student who might be struggling mentally.