It’s been a very long time since I thought about the Black Papers, and I’m not sure whether to thank UPP, HEPI, and Public First for the reminder.

Kingsley Amis wasn’t just a novelist and poet – he taught English at University College Swansea (now Swansea University) for about a decade, writing archetypal campus novel Lucky Jim during this period. But that wasn’t all he wrote – towards the end of his tenure he settled into carping about mass education and making arguments for elitism as a motivating principle for what I guess I can now call skills planning.

“MORE MEANS WORSE” is the old saw that UPP’s Richard Brabner and HEPI’s Nick Hillman reach for in the introduction to a survey of public attitudes to higher education (of 2,011 adults recruited via online panels and weighted by age and sex, region of residence, and social grade – carried out by Public First). It comes from a 1960 Kingsley Amis Encounter piece entitled “Lone Voices”.

A Swansea academic writes

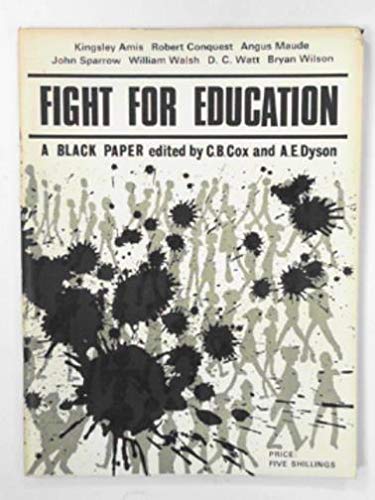

To be fair, it’s a class above your usual letter from an aggrieved academic in terms of style though you do have to read a fair few words about how terrible the 50s and Americanisation are before you get to the money-shot, as it were, on how more graduates means worse graduates. But this isn’t just one disillusioned history man (to mix literary metaphors for the moment) railing against his advancing years and declining proclivities – it’s an early signal of a trend in public thought around education policy diametrically opposed to CP Snow’s techno-optimism (The Two Cultures – via maybe the Robbins Report) of the same time. We had to wait till 1969 for this strand of thought to fully enter the mainstream – after Wilson’s “white heat” technological revolution had subsided a bit – via the Black Papers (Brian Cox, AE Dyson, Angus Maude, Rhodes Boyson and – yes – Kingsley Amis).

Though that’s quite the political spectrum – including an LGBT rights pioneer and a noted homophobe and corporal punishment enthusiast – the papers (actually a series of special issues of Critical Quarterly published to initial furore and waning influence) could be seen as the flowering of a traditionalist romantic utilitarianism that has percolated through popular thinking on education ever since. Broadly characterised – education used to be better (these progressive ideas are terrible!), only people who could really benefit from it got the good stuff, this gave us the stratified society and promoted the natural leadership that led us to the Suez Crisis – it’s still recognisable, and influential in 2021.

Future echoes

Why do I say that? Well, results from the HEPI/UPP survey show the ideas of these mid-century academics and public intellectuals as significant in the general public perceptions of higher education now. Though the thrust of the argument then was pro-grammar schools but only for the best – we could see university now as the grammar school writ large.

Twenty-seven percent of our sample feels that there should be a smaller proportion of the population going to university than there currently is. That’s not the plurality (36 per cent think the current proportion is right), but just 17 per cent support expansion. The likelihood of holding this view increases by age (up to 43 per cent in the over 65s!) and right wing voting habits (Conservative in 2019 36 per cent, Brexit Party in 2019 46 per cent). There’s not a great difference by education level, though the opinion tends to be more widely held where neither parent attended university.

We don’t get the cross tabulations that might tell us why with respect to other views – the characteristics splits (older, Conservative) suggest to me that belief in the virtues of a smaller sector has become a received opinion. Interesting the lasting impacts that the opinions of a bunch of academics and writers 70 years ago has had.

Definitions in data

Arguably, the current loggerheads at which the sector and government sit is based on a similarly precarious commonplace as free speech debates tend to be. Canny politicians and also Gavin Williamson know that leaning in to stuff everyone knows (“exams are the best way to assess potential”, for christssake!) is the best way to push through pet policies.

Take, for example, “decolonisation”. A perfectly fair and reasonable academic term for the process of accounting for and listening to the voices of those who suffered and continue to suffer at the sharp end of history and politics. As the survey notes, if you ask the public how it feels about “decolonisation” you get 29 per cent who disagree with the idea (our instinctual culture warriors) plus 16 per cent who don’t have a clue what you are talking about and 33 per cent who don’t feel they know enough either way.

Flip that to asking about curricula “allowing students to study about (sic) people, events, materials and subjects from around the world, and ensure that all groups are represented fairly and discussed in an even-handed way” and you get 65 per cent of the public in favour. It’s maybe not quite as stark as the data paints it – “decolonisation” is said to somehow mean actively “removing material” which reflects a “western dominated” view of the world. That’s what Michelle Donelan thinks decolonisation is, but it isn’t what anyone who actually wants to do it thinks – and it’s a debate that’s been in play since round about the time Amis was writing in the late 50s, so we can’t really blame novelty.

The appetite for higher study

We can apply this same idea around wording to other responses about the use of universities. The “other people’s children” meme – the idea that too many people go to university, but you and your children are not the “too many” – is a powerful one, and there is more evidence for it’s prevalence here. A clear 48 per cent would definitely or probably want their children to go to university – just 23 per cent feel that it is unimportant for a person to get a university degree.

A third of those who did not go to university would want to do so if they were leaving school now, two thirds of those who did attend university would still do so. Those who did not go to university themselves would (narrowly) not want their children to go, but there is not much in it.

Parental university experience is a valuable predictor here – just eight per cent of those where both parents went to university (twenty per cent where one parent did) would not want to go now. And just 19 per cent of the sample feel that university is a waste of time – and on this question both parental university experience and the age gradient slants the other way. If you think that this seems curious you are right to do so.

There is a temptation in survey analysis to assume that a set of responses from a person is equivalent to a coherent philosophy – this could not be further from the truth. People respond to survey questions largely instinctually – wording and phraseology is hugely influential, and even an echo of a common idea can make a huge difference. That’s not to say that framing changes everything, not even the Nudge Unit believes that, but survey design is an art rather than a science.

I don’t know whether culture wars end when we agree on a common vocabulary, I don’t know whether a stable, neutral ontology will stop government attacks on the sector or vice-versa. But I do know that memes – even pensionable age ones like the curious conceptualisation of education in the Black Papers – are stubborn and long lasting mental hooks into the mind of the nation.

I remember reading about the Black Papers at the time in the late 1960’s when around 5% of the population went to a university but would guess that fewer than 2% of the population actually read the Black Papers, so I wonder how much influence they had. Today, with around 50% of the population going to university I am not surprised at the results of the survey nor at the relatively high percentage of “don’t knows”. As for what the results “mean”, or suggest we should do, I am even more reserved. As “Attending University” is such a “wide church”… Read more »