Predicting the course of the pandemic has proved to be a difficult game over the past fourteen months or so, but a bit of it becomes necessary as “gold command” committees all get wound down and “what will September look like” ones pop up in their place.

It is now 51 weeks since the universities of Bolton and Cambridge respectively announced their delivery plans for September 2020, prompting almost every other higher education provider in the country to panic-announce something similarly “blended” in the weeks that followed.

So on the assumption that we’re about to get a press release from the Office for Students declaring that students need “ABSOLUTE CLARITY” about what will be on offer in September, I thought I’d round up where it looks like we are and where it looks like we’ll be by the Autumn – and see if we might make something meaningful out of the “blended” pronouncements to come.

Yes but does it extrapolate

The first consideration has to be the overall progress of the pandemic itself.

There will have been a bit of pre-election boosterism in there, but Westminster Vaccines Minister Nadhim Zahawi suggested the other day that we’re still on track for legal limits to all go in a few weeks:

And we get ourselves away from this pandemic and into a world where we deal with it the way we deal with the flu virus, with an annual vaccination programme from next year onwards.”

It’s hard to overstate how cautious the Westminster government has been over this part of the pandemic. It has been cautious when evaluating SAGE’s advice and SAGE itself has been cautious in its predictions.

Some of the caution is about multi-layered back covering, some of it is about influencing public behaviour, some of it is about not repeating previous mistakes, some of it is about chips in the bank for any public enquiry that will follow, and some of it is about genuinely not wanting there to be another lockdown.

If vaccines work but maybe not on new variants, there is in truth an interesting debate now about whether to glide towards a containment strategy focussed on the UK’s borders or one focused on social distancing and staying indoors – a dilemma that’s summed up well in this Ian Dunt piece on Chile and holidays. The way that strategy develops could well have a meaningful impact on international student arrivals – at least from a quarantining point of view.

Of course the bigger issue when it comes to international students is clearly the progress of the pandemic internationally generally, and both vaccination and variants specifically in the major markets from which the UK recruits. The marked contrast between stories about Boris’ £1bn Indian trade deal and stories about desperate Indian students not being able to afford to get into the UK (and in many cases pay their fees for this term) ahead of the June 21st deadline for the graduate route has felt especially uncomfortable.

But make no mistake – this is a government that believes that there will be no more lockdowns, that the pandemic can be managed like a flu from here on in, and will retain the lightest of sensible guidance-based restrictions around indoor activity for the foreseeable. Maybe there will be some whack-a-mole over flare ups. Even where the tone is different – and I know Mark Drakeford’s suggestion that social distancing might remain for a while in Wales has caused all sorts of strategic consternation in the working groups – that’s more about his own political image and mood music ahead of his own election than reality.

Come inside

All of that gets us to consideration of what can and can’t be done indoors – and crucially, what any guidance will mandate about social distancing. There’s actually still a strong possibility that the relaxation of social distancing requirements indoors becomes linked to vaccination. Pubs and restaurants might have been taken out of the government’s vaccine passport thinking, but universities and colleges haven’t – and neither have halls of residence. And a vaccine mandate is certainly not off the table in many of the settings where students might be on placement.

It would suit the Westminster government to give the job of improving vaccine take up among the young to organisations like colleges and universities, and despite the major EDI and human rights issues involved, providers that then used their autonomy to say “we’re not maximising the amount of teaching on offer and we’re not using this to improve vaccine take up” aren’t going to look very popular as the refusal numbers stack up.

But the overall point here is that it’s looking increasingly unlikely – vaccine passports or not – that a university is going to be told that it must retain any social distancing indoors. And in truth, for most universities that are dead keen on retaining a “blended learning approach”, that’s a bit of a pain in the backside – because the space constraints generated by “oh it has to be 2m+” are the gateway drug to “we’re now a blended learning university”.

Depending on who you are, where you are, where you recruit from and so on and so on, some of the reasons that that’s a problem are easier to admit in public than others:

- You believe in blended. Students and staff have praised the flexibility of online.

- If a bunch of teaching is online, you can save on capital costs in the long term, and things like energy in the short term. Lots of that is just passing the cost on the individual, but hey ho. It’s the future.

- You’re not sure about international arrivals and are keen to show that enrolment could take place and the academic year begin without them having to be here.

- Timetabling was already fraught before the pandemic, and delivering a whole raft of teaching hours online solves the problem at a stroke.

- If you’re considering emergency-expanding in the wake of grade inflation or even the wider analyses that take in the counter-cyclicals of a recession, it’s a lot easier to do if you broadcast rather than house your lectures – because it’s only the other bits that then need more bodies.

- Keep your provision blended and it opens new possibilities to enrol distance learning students generally.

But there are also major barriers.

Why am I here

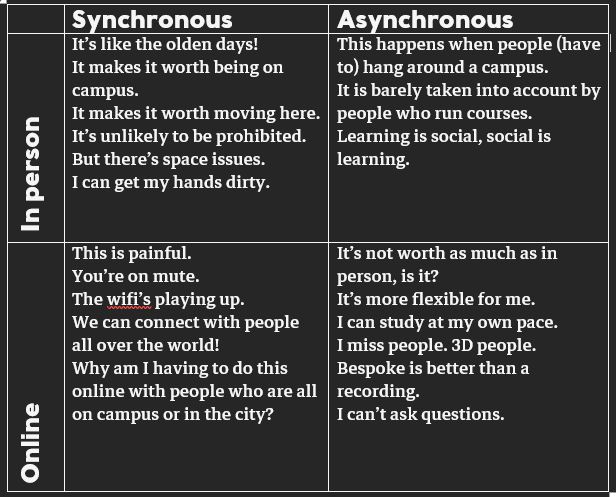

Whether students have moved halfway around the world, halfway across the country or even just battled their way in on the bus, we shouldn’t underestimate quite how upset many of them will be at having to spend some of that time taking part in teaching online – and “having” is the word to watch.

Loving the flexibility of accessing a recorded lecture now that everyone’s pressing the button on Panopto is one thing. Not being able to experience it in person is quite another. Mix in the general desire we’ll all have for in-person everything by the Autumn, and Zoom calls with people who are all in the same city (or even on the same campus) are going to sound absolutely ridiculous. Why did you make me come here?

There are access issues. If any of the teaching in a “blended” mix “has” to be experienced online, then without the cushion of pandemic excuses someone, somewhere needs to fix the digital divide and space-to-learn issues for every single student that’s facing them. Unless we’re suggesting that 1000s of people during every hour of the timetable will be piled into PC labs and social learning spaces, interacting with others through their airpods.

There’s significant consumer protection law issues. Continuing students were told (and sold) an in-person experience that has been suspended because of the pandemic. If we want to “teach out” the in-person lot, then the issues go away. If not, and the (already questionable) legal excuse has gone, what right has a provider to move teaching online that was promised in-person?

We’d need to be realistic about some of the contradictions thrown up by last autumn. It didn’t make any sense last September to run campuses at 30% occupancy but halls of residence at 100% occupancy, and it will make even less sense to do so this coming September.

There are competition issues. Imagine next week five universities feel confident enough to say “we can guarantee that all our teaching next year will be in person and as much of that as possible will also be recorded”, accompanied by flashing gifs for the UCAS website of students hugging each other. It would be a bold university that thought to itself “we’ll just say blended and cross our fingers”.

At some stage students will work out how to tell between “blended” that’s about choice and flexibility for them, and the version that’s more about choice and flexibility for their provider. At another stage those in the trenches competing for students will notice that the trickle of US colleges opting for a vaccine mandate so they can all but guarantee the in-person experience has already turned into a flood and an interest and application bounce to boot.

There are major staff issues if “hyflex” becomes an expectation. There are vanishingly few courses which can be taught both in-person and online all at the same time, and dual approaches that demand anything more than recordings of in-person activity are beyond the hours in most contracts outside of a pandemic.

And there are real mental health and satisfaction issues too. The latest ONS data reminds us that students who are being taught in-person are happier and more satisfied. Why would we ignore all of that?

Student-centred approach

But most importantly of all, there are issues that should go to the heart of decision making and planning but seemingly never do.

You might remember that last year when everyone was discussing how to timetable their teaching and make it “Covid-secure”, I sketched out a model off the back of a meeting with some course reps of how we should think about a student’s week.

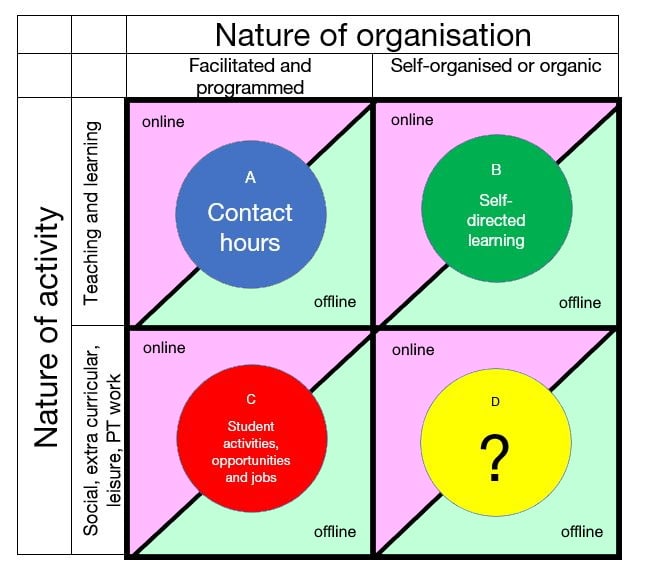

I identified three “either-or”s in the model:

- The first differentiates between what I would call “teaching and learning” activity and wider social or extra-curricular activity (it’s all educational, by the way);

- The second differentiates between that which is timetabled, programmed and formally facilitated, and that which just organically “happens”;

- And the third (the diagonal line splits) differentiates between whether activities are envisaged to be, likely to be or even possible to be in-person or online.

My worry then was that while people had perfected how they’d deliver the tiny handful of teaching hours that a student experiences, they’d failed to consider quite how miserable the rest of a student’s week was going to be if we lured them to campus – a classic “wrong end of the telescope” student experience mistake.

What’s extraordinary is the sense I have that we could be about to make the same mistake all over again, only in reverse.

If it’s the case that boxes B, C and D all can (and likely will) involve people mixing, hugging and sweating indoors, it would be utterly surreal for us to insist on dollops of activity in box A being online. “Yeah mum”, says the student a month in, “I’m in a 100% occuipancy hall, last night I was in a nightclub, I’m off to a film screening tonight, I’m working in a packed bar tomorrow, and I’ll be on a full coach on a trip on Thursday. But my actual teaching is on Teams and Eduroam keeps cutting out”. Seriously?

And where that all gets us to – both predictably and prosaically – is where we’ve always been. Education is best designed by those who receive it and those who deliver it. Students and staff have been through the ringer over the past year – the former have had less than they paid for, and the latter have delivered more than they were paid for. What they need now is the support and space to come out of the pandemic together and determine what will work best as we all rebuild our confidence, our optimism and our mental health.

The march of technology and the amazing possibilities it offers to connect globally and reduce commuting times and provide access to recordings of lectures on a phone on a bus aren’t going away. But if I learned anything in my first ever (in person) lecture at UWE in 1995, it’s that it’s not technology that determines the development of a society’s social structure and cultural values, it’s the other way around.