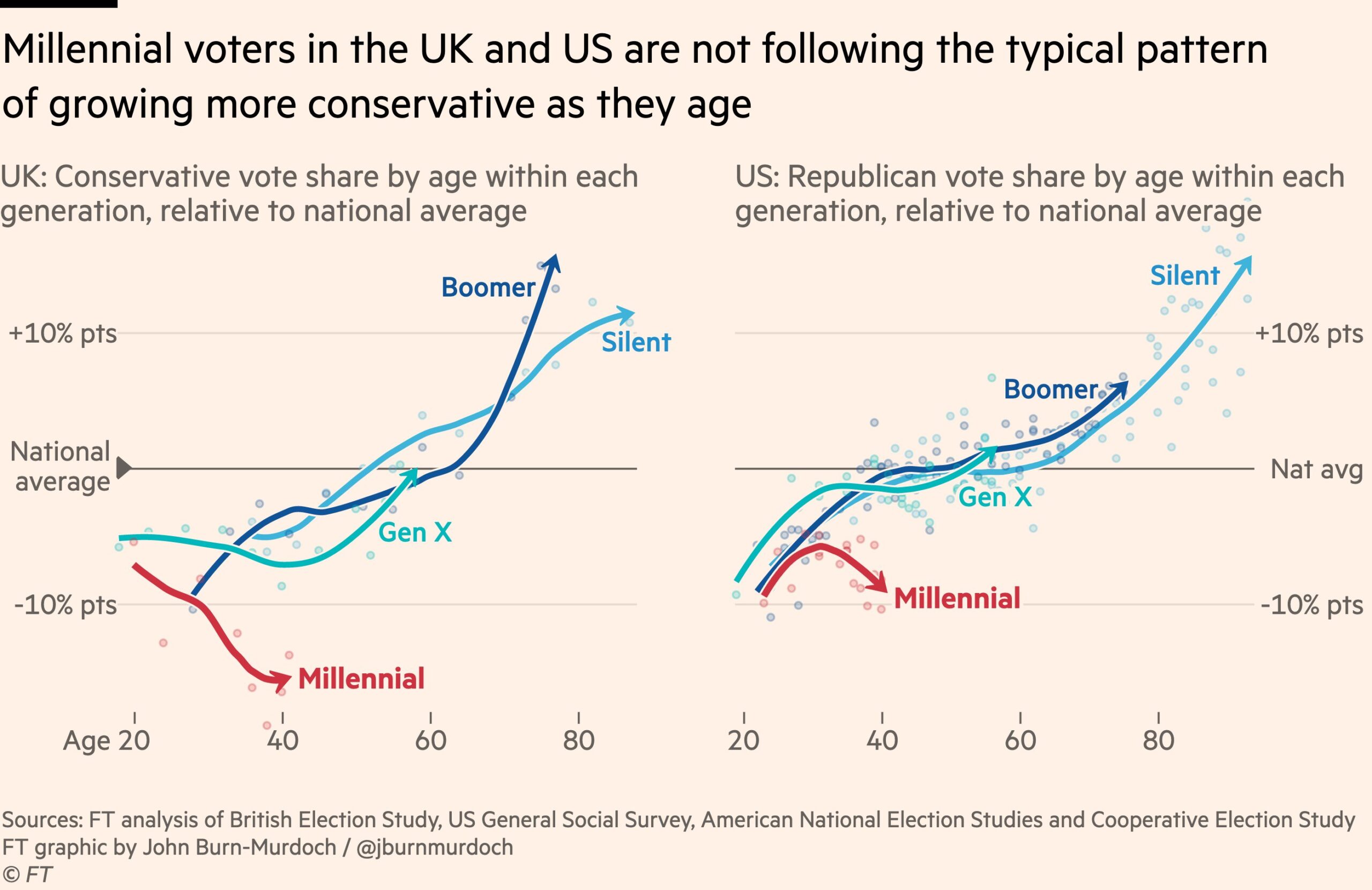

A couple of weeks ago the FT’s John Burn-Murdoch went viral with one of those Twitter threads weighing up why young people – on both sides of the Atlantic – aren’t voting Conservative.

The narrative is that conservatives have a problem because an old iron law age effect in politics – that people move to the right as they get older – doesn’t seem to be holding.

As a reminder, age effects are changes that happen over your life regardless of when you are born, period effects are based on events that affect all ages simultaneously, and cohort effects are carried by those who experience a common event at the same time.

Some think it’s down to period effects like Brexit and Covid, and will fade. Others think it’s likely still an age effect – but delayed because of the growing average at which people marry, own property and have kids.

Burn-Murdoch reckons it’s probably a cohort effect – millennials moving much further to the left on economics than previous generations did, favouring greater redistribution from rich to poor.

As ever with these sorts of analyses, in the accompanying piece, there’s a problematic mix of “left v right” and “conservative v labour” (or “republican v democrat”), as if the positions and platforms of the parties are consistent.

There’s also ongoing confusion about whether support for Labour/Democrat signals a view on attitudes to economics, social issues, or both.

But what is clear is that in the coming general election that the country will spend much of this year discussing, students are highly unlikely to vote Conservative.

And given how many students there are these days, and the potential that the “student effect” is both more significant than in the past and lasting longer (if not forever), we could really do with knowing more about what’s really going on – and whether the sector is causing it.

Because if it’s true that mass participation in largely residential higher education can wield this much political influence, there are implications – especially for countries with two-party systems that wish to grow their graduate base.

Pros and conservatives

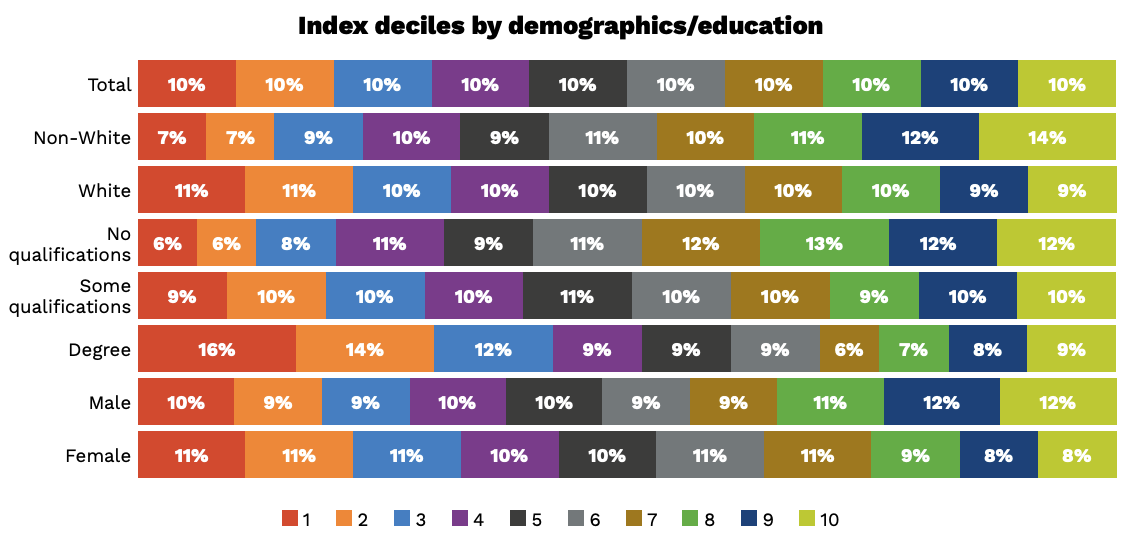

One helpful set of clues as to what’s going on can be found in a fairly overlooked piece of polling carried out for Hope not Hate late last year. On the social attitudes stuff, it polled on four issues – identity, politics, multiculturalism and conspiracy – with some of the starkest differences being about the level of qualification attained:

Your eyes – as mine did – may drift to the left of that chart, where 0 means most liberal on identity and politics, most pro-multicultural and least conspiratorial. Depending on your politics, that will either cheer you up or annoy you.

But the percentages on the right hand side, while smaller, are hard to ignore. And anyway, isn’t all of this just likely to be a reflection of youth, given the participation rate has been growing?

A closer look at age, therefore, is interesting. A previous version of the Hope not Hate work from 2020 polled 18-24s on their views – and when it came to social attitudes, younger people tended to be more socially liberal, and had a more open view on issues such as multiculturalism and immigration.

Just 17 per cent of 18-24 year olds thought that immigration had been a bad thing for the country, compared to 73 per cent of 25-34s, 37 per cent of 35-44s, 40 per cent of 45-54s, 44 per cent of 55-64s and 37 per cent of those over 65.

More than half (54 per cent) of young people from African backgrounds had experienced racism on social media, while young people from BAME groups were all more likely to have seen or witnessed violence or threats of violence.

And sexual violence was worryingly prevalent among young people. Almost a third of young women (29 per cent) said they had seen or experienced sexual harassment and 14 per cent said they had seen or experienced sexual assault.

That might all lead us to think that even if Labour says little, a Conservative Party stoking the culture wars is on a hiding to nothing when it comes to this cohort. But what about the economy, stupid?

Progressives and cons

This time a third of young people said that they were disappointed with their lives so far, with young people in low income households or unemployed young people most likely to feel that way. In addition:

- Only half of young people thought that in five years’ time, they would have a good job and a decent place to live. Those with university degrees were more confident (63 per cent) while only 40 per cent of young people in the North East thought they would, compared to 53 per cent of people in the South East.

- While there were not very large gender divides in what young people wanted from the future, young women were more likely to put pressure on themselves for the future than young men, and more likely to see all of the aspects listed above as important for their futures.

- BAME young people were more likely to place importance on a university degree. But overall, fewer young people thought that going to university was essential to get a good job (37 per cent) than thought a degree was not necessary to get a good job (63 per cent).

Governing against the economic interests of the young for the best part of a decade won’t have helped the Conservatives’ cause here. And I need not restate what’s becoming a cliche in terms of what to do about it.

It’s almost certainly unwise from a cohesion perspective for a society’s politics to be so bifurcated between young and old. But having the money to do something about it as the population ages is a different question.

We also still don’t know whether we’re witnessing cohort, period or age, and what the differences are (if any) between students and non-students.

OK, Boomer

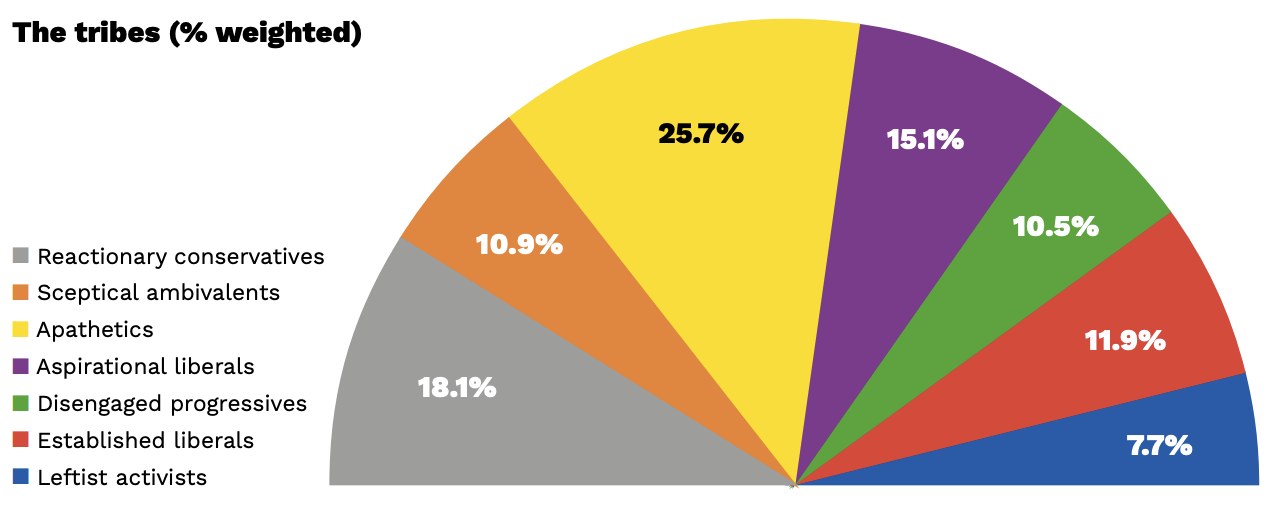

Helpfully, rather than just polling on voting intention and in addition to the work on particular issues, the work from 2020 used a segmentation model of seven groups of 18-24s – each containing people with a similar worldview, helping to explain how views on particular issues interact and overlap.

It argued that because young people are overall more socially liberal, it is unhelpful to just lump the young together into a box called “socially liberal”. Instead it identified several groups who held progressive views, although held these to different strengths and place value on different things.

And the thing about groups is that once you’re in them, unless something major in your life changes, you stay in them. Especially in an age of social media.

The groups were:

- Reactionary conservatives (18 per cent) – hold the most conservative views – more likely to feel disenfranchised and reject political correctness and there is a proportion, although small, within this group who engage with racist conspiracies and far right ideologies.

- Sceptical ambivalents (11 per cent) – have mixed views on social issues, but generally feel they are well represented by the political system.

- Apathetic (26 per cent) – a relatively large section, who are largely indifferent around political issues.

- Aspirational liberals (15 per cent) – hold socially progressive views, but their focus is away from politics and more towards their own prospects.

- Disengaged progressives (11 per cent) – share similar social views, but feel detached from the political system.

- Established liberals and leftist activists (about 12 and 8 per cent respectively) – hold very strong progressive values, although the former embrace the political system whereas the latter reject mainstream politics and don’t trust the government.

But what’s interesting is the way in which the student profile differed from that spread:

- Reactionary conservatives: 15 per cent (18 per cent of 18-24s)

- Sceptical ambivalents: 7 per cent (11 per cent of 18-24s)

- Apathetic: 24 per cent (26 per cent of 18-24s)

- Aspirational liberals: 19 per cent (15 per cent of 18 to 24s)

- Disengaged progressives: 12 per cent (11 per cent of 18 to 24s)

- Leftist activists: 8 per cent (7 per cent of 18 to 24s)

- Established liberals: 16 per cent (12 per cent of 18 to 24s)

If we assume that despite all of the Starmer triangulation that’s to come, the aspirational liberals and established liberals will all vote Labour, and a good chunk of the sceptics, progressives and leftists will be arm-twisted to do so, you’re looking at almost half of students putting a cross next to the red rose.

If that ends up being the result, depending on your perspective either “higher” education caused it, or the higher education that we have failed to correct it.

Either way – if you’re a Conservative minister or strategist, once you’ve realised that appointing a right-wing candidate as the OfS free speech champion isn’t moving the electoral dial, you will face a long term choice. You can change the nature of the education on offer, reduce the numbers going into it, or change your own party’s positions on things.

Much of the political consensus I’ve read has its head firmly in the rear view mirror – assuming that from the ashes of near-inevitable defeat, a Cameroonian figure will at some stage emerge to hug some huskies and hoodies and reclaim the “centre ground”, and some young people with it.

I neither think that to be likely nor something that will work, at least in the short term. I suspect there are few in the sector that would want to play along with reducing numbers. And all of the “change what is taught” or “regulate debating societies better” arguments seem to misunderstand how higher education teaching or social capital acquisition works.

So maybe we should also think about what a Starmer-led “no big cheque book” government might do too.

If you’re a Labour policy maker, given all of the other pressures on spending, you’re both going to want to know exactly what it is about higher education that supposedly causes this shift towards progressive, liberal positions before you accede – and you’re going to need to minimise any downsides.

And on that front, trouble is coming.

The decade ahead

It is difficult, in all honesty, to assume that it is at all possible to rob future-Peter to pay now-Paul and load even more of the current costs of higher education onto graduates. That is a trick that has been pulled multiple times over the past thirty years – and following this summer’s round of stealth changes, is one that likely can’t be substantially pulled again.

Some believe that making economic arguments will suffice – that whittling up figures showing the impact of students on local economies, or the graduate premium, or the wider impact of research, will do the trick. But when the choices are international or home domiciled away-from-home students overheating the local rental market, with proceeds off to pension funds and landlords, it’s not clear that the pie charts will work.

Almost three years ago to the day, now my colleague Debbie McVitty said on the site that it was possible to imagine a future in which higher education provision looks roughly as it does now, only on a larger scale:

Government could adjust the loan repayment system to reduce the public cost of unrepaid student loans, and if no steps were taken to restrict student numbers there’s every possibility that we’d see a repeat of the nineties in which universities took in more students at a declining unit of resource in real terms, but without significantly transforming provision to mitigate against the impact on quality and student experience.

Well, the future is here now. But it’s what she said next that was really interesting:

In that scenario, the residential model of higher education would come under pressure as never before, as university services and systems creaked under the strain of delivering anything that looked like a “student experience” at scale. Local councils and regional mayors would likely take radical steps to mitigate the impact of studentification on their local community, with issues around accommodation, nightlife, parking, and access to local services. Student financial hardship – if not addressed through a generous financial settlement – would only worsen.

Now consider the central message of Starmer’s big speech last week:

It’s not unreasonable for us to recognise the desire for communities to stand on their own feet. It’s what Take Back Control meant. The control people want is control over their lives and their community. So we will embrace the Take Back Control message. But we’ll turn it from a slogan to a solution. From a catchphrase into change. We will spread control out of Westminster. Devolve new powers over employment support, transport, energy, climate change, housing, culture, childcare provision and how councils run their finances. And we’ll give communities a new right to request powers which go beyond this.

The point is that for the Conservatives, expanding the boarding school model will remain toxic – universities under this idea are out of control, left-wing madrassas inculcating wokeism into the impressionable young. And for Labour, a quasi-tourism model designed to hothouse the young elite by skimming them out of where they live now is expensive, profoundly anti-community and ultimately unsustainable – principally because we don’t have enough housing to sustain it.

If you’re sceptical about that argument, just think about what relieving half a million people from having to rent in our biggest towns and cities would do to the economic prospects of the young, the prospects of multiple regions and the intergenerational relationships and misunderstandings that persist now. And to the cost of funding HE.

And that’s what routes us around to where I think the consensus will land. If it’s true that only residential higher education delivers the “real” benefits of higher education, the question the sector should ask itself in the next decade is not how to maintain and grow the numbers that leave home to study – with the money and halls to match – but why on earth it has ended up in a situation where the benefits disproportionately flow to those who do.

Unless you’re studying something particularly specialist, it should be possible – and is surely deeply desirable – to build community, foster understanding, gain skills, develop independence and understand other perspectives wherever you’ve arrived from. The number one goal should be for commuters to feel more “normal” than everyone else. The climate needs it to happen, communities need it to happen, and anyway – hyper competition has come to the end of whatever usefulness it had.

If there are economic benefits to HE participation, don’t we need to do as much of Europe does, and spread those benefits more equitably around the country – rather than telling ourselves that loans to pay the rent that prop up pensions and hedge funds are somehow good for the people of Chester and Chichester?

Transformation within communities, rather than by lifting people out of them, will become a consensus political goal. Political parties will argue over how to do it – but they’ll argue even more with those who reject it.

You make some really,interesting arguments. I disagree with a couple of the assumptions though. Firstly, it would be very difficult to replicate the benefits of the boarding school model of HE in the UK without the boarding. It’s not just attending your classes where you derive the benefits, it’s living and socialising with your peers 24/7. There is just no way the younger working class me would have derived all the benefits getting on a train and attending lectures, doing the odd social event and then going home to my overcrowded terraced house to hang out with my mates. Second,… Read more »

Interesting piece. Note that the quotes in the final part of your article in the final part of your article about the residential model of HE coming under pressure are misattributed – they were made by Debbie McVitty

Thanks @peter – we’ve made that correction!

The graph at the top really rings true for me, and I found the article really thought-provoking.

I’ve recently wondered about the extent to which factors such as climate change may be a contributing factor. i.e. The notion that we are collectively responsible for the planet, and that notion of collective responsibility aligning with the views of “the left” (though, for example, https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/who-cares-about-climate-change.pdf doesn’t back this up).

Thanks Jim. I found the article harder to follow than your typical ones. Your analysis about the index decile chart is a bit confusing as the scale starts at 1 (rather than ‘0’ as you say). Also, was it really 73% of 25-34 y/o in the poll who thought immigration is a bad thing or did you mean 37%?