For those of us that have been around higher education for a while, the idea that campuses are hotbeds of left wing student radicalism – certainly in comparison to the 70s, 80s or even 90s – is fairly laughable.

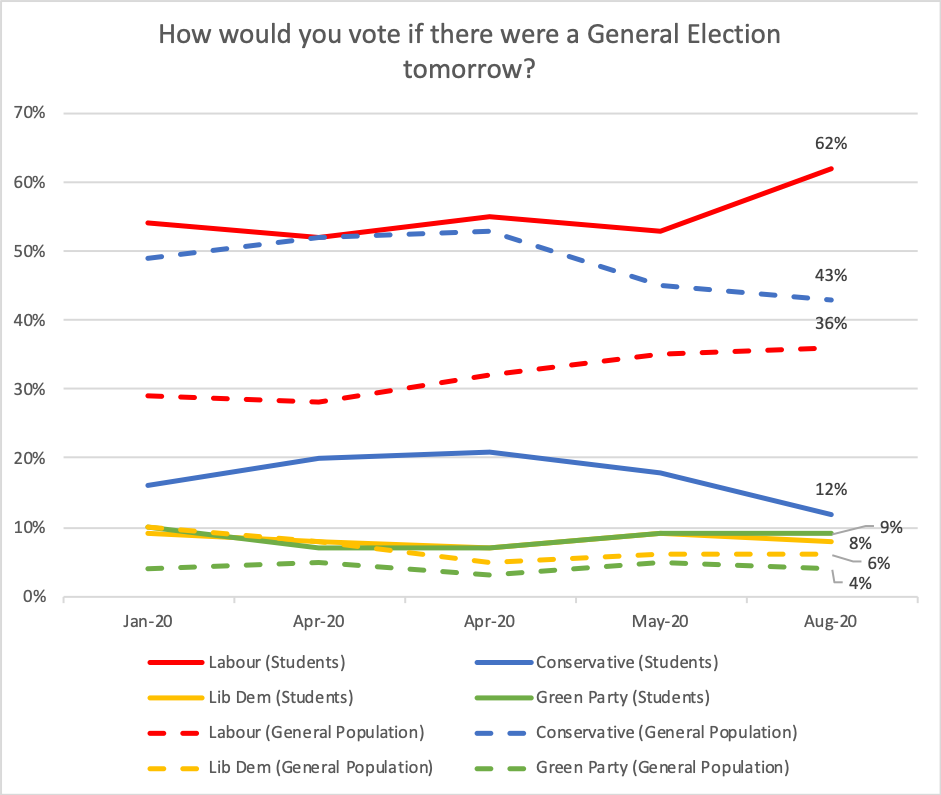

But to read some Conservative commentators you would think the reverse is true. And to be fair, new HEPI/YouthSight polling data shows more students would vote, and vote Labour today, than for a long time.

When David Willetts said in 2007 that “these days, students are more likely to have posters of Boris Johnson than Che Guevara”, he was probably right. So what has changed since? Has Boris moved away from students or has cancel culture and wokeism pushed students back to Che Guevara, or “Jeremy Corbyn” if you were watching that episode of Newsnight?

Live is life

For as long as I can remember, students generally being quite left wing was assumed to be a life cycle effect – where people’s attitudes change as they age.

Couple that with the small proportion of students that tended to vote, and the small proportion of the population that actually went to university, and students being left-wing was generally filed under “amusing dalliance” rather than “existential problem for the Conservative party”.

Lots has changed, of course. “Blair’s 50% target” has driven up participation, and HEPI/YouthSight says that a greater proportion of them would vote in an election tomorrow than ever before, at a stable 83-84 per cent up from the mid-60s per cent in the noughties.

And on the face of it, they’re more “left wing” than ever. The new HEPI/YouthSight figures put “much more moderate than Jezza” Keir Starmer’s Labour on 62 per cent among students, with the Conservatives languishing on 12 per cent.

Given there’s also wider evidence that what used to be a life cycle effect might be becoming a cohort effect (where a whole group has different views and these stay different over time), and you get two responses – some Conservatives panic about universities indoctrinating students, and others just give up on students and the young, and double down on an ageing population. Some do both.

When we all feel the power

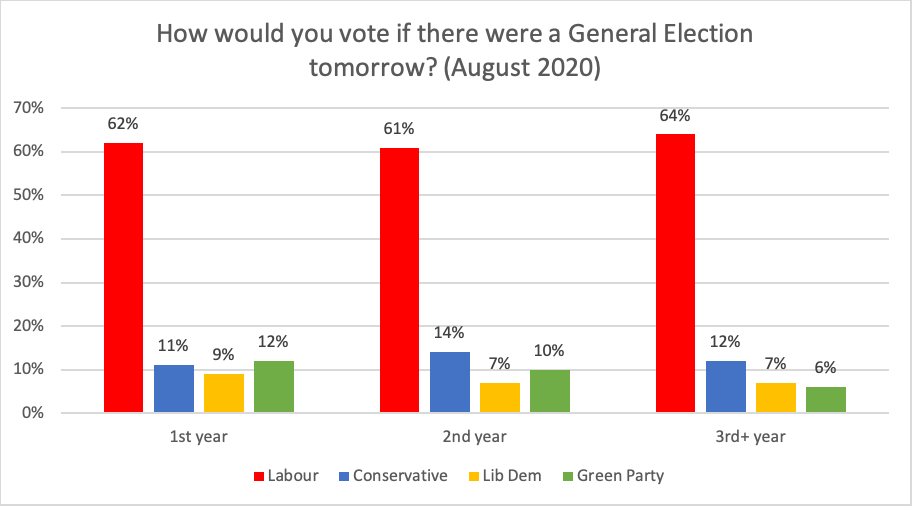

The HEPI/YouthSight figures are interesting – they don’t suggest that students’ views change much over time at university, so to justify the “left-wing madrassas” claim you’d have to believe that the entirety of the indoctrination effect happens in an undergraduate’s first year. Sadly YouthSight doesn’t collect applicant voting intentions – but comparisons with the rest of the “young” don’t suggest that Conservatives do much better with non-students.

Compared to 18-24 year olds in general (and yes I know mature students exist but this is all we have for comparison), support for Labour is twelve percentage points worse than amongst students exclusively. But it’s not Conservatives that non-students swing to – support for Conservatives is similar (14 per cent). Whatever’s going on with minor parties for non-students, the evidence isn’t exactly piling up for the indoctrination claim.

On the life cycle or cohort effect, there is a theory that people become more conservative in general when they start to own a home, get married, have kids or settle on a career. We’ve talked on the site before about long term changes to life expectancy and the economy that seem to be pushing those life events later and later, generating a new “middle stage” where it’s not a daft assumption that graduates will retain their leftish views for another decade or so.

The question for Conservative strategists is whether that “middle stage” is so long that opinions harden. If not, and we still switch once we get a mortgage, you can soak up the old and re-run the Brexit referendum at every election – remember the Conservatives’ vote share among the over-65s was more than 60 per cent last year. But if opinions do harden, the Conservatives are in long-term trouble.

This is the sort of stuff that drives debates about “too many people going to university”, or even the bizarre broadside at students’ unions that we saw at the weekend. What’s strange is the things missing from the debate.

And everyone gives everything and every song

Generation Why?, a report from the Conservative think tank Onward last year, revealed that the median age at which a voter becomes more likely to support the Conservatives than Labour had risen by four years, from 47 to 51. According to Onward, millions of these young people would consider voting Conservative if the “the policies and values were right”.

That’s an interesting proposition because evidence suggests that voting intentions of the young are often more about a party’s positions than older voters, who tend more to respond to matters of ideology and the politics of identity (!) But if issues and policy matter to the young, we should note that the Conservatives had almost no “retail offer” for students or graduates in 2017 where Labour had lots to say – something that Theresa May specifically responded to by calling the Augar review (students) and by lowering the loan repayment threshold (graduates) in that famous “croaky voice speech” at party conference.

Despite all of that, there was still no meaningful retail offer at last year’s election – in fact if anything the party appeared to double down and deliberately went for a short manifesto. Anna Firth, who lost Canterbury in 2019 for the Conservatives, figured on ConHome that the party needed “aspirational” polices focused on the environment, opportunity and home ownership. So is it really that students are “more left wing” – or is it in fact that students “tend to be attracted to policies that speak to their dire economic prospects” and “do want to see something on the climate crisis”?

We should note that when almost all Conservative HE ministers have addressed “students”, they’ve really meant “applicants”, and by proxy “their families” – just look at Michelle Donelan’s work since the pandemic struck. Isn’t it more than a little defeatist to assume that once students enrol, they’re a lost cause unless you somehow sack left wing academics and ban no platforming? Doesn’t there need to be a positive, rather than just the eradication of a vaguely mythical negative?

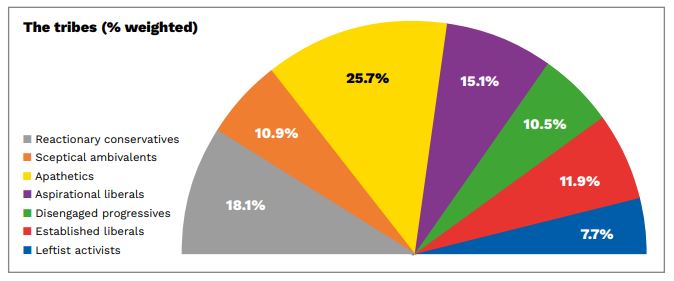

The other thing that polling tends to do is conflate “voting Labour” with “being left wing” and “voting Conservative” with “being right wing”. But political parties shift – to embrace their centrist wing (see Labour this year) or to reject it (see the Conservatives since Brexit). These fascinating figures from a Hope not Hate study on the young from earlier this year suggest that students are pretty diverse – and maybe it’s therefore how parties play their own centre that determines who will get an unusually large slice of young people at an election.

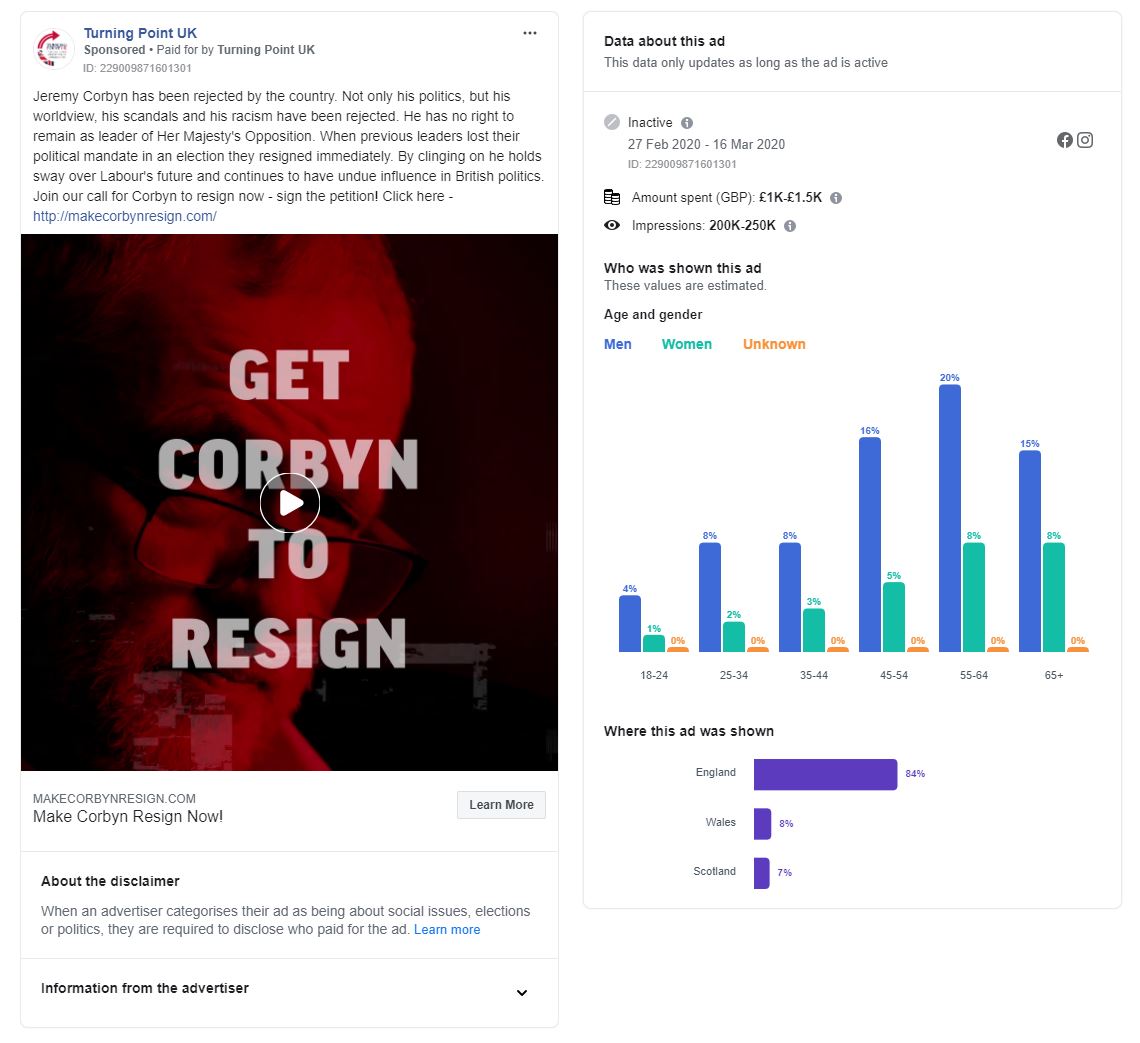

As noted above, there are Conservatives who want to court the young. But don’t confuse them with right-wing libertarian “youth” movements – many think they may really be about comforting the old instead. Turning Point UK, for example, may stand for free markets and small government, and for those who are “sick of snowflakes spouting nonsense” and “let down by the left-wing bias” of UK universities. But for some reason the people reading their Facebook ads don’t fit the usual profile of a “youth and student movement”:

The bottom line is that students and the young will probably always lean to the left to some degree – and there’s not a lot of evidence that universities cause that. The question is whether the Conservatives think that long term, they need an “economic/opportunity” offer for people in their 20s, or instead should turn on their “snowflake wokeism” to shore up their increasingly elderly base. At this stage it could go either way.

Sadly, coming up with an attractive policy offer takes time and costs money. It’s much easier to hurl abuse, at least, it is in the short term…