“Universities here might not think that they’re selling economic migration – but that is what we think we are buying.”

That was one of the more arresting quotes from a students’ union officer that we’ve been spending some time talking to over the past few weeks, as we’ve tried to get our heads around the remarkable increase in Nigerians and their dependents coming to the UK on the student immigration route.

The concerns that abound from SUs have mainly focused on meeting the immediate needs of the students that the sector has been recruiting – family accommodation, childcare and pregnancy is one thing; timetabling that facilitates participation when living and working near to campus is impossible is another; problems with finance and banks are common; and student hardship policies that recognise that the UK is spectacularly more expensive than we warned students about matter too.

But one thing we keep coming across is a deep desire to avoid even talking about these things on campus. We’ve now heard of too many SU officers in too many meetings who raise the issues facing Nigerian students who get met with uncomfortable silences to dismiss those stories as isolated anecdotes.

“Let’s take that offline” responses, and head-in-the-sand style “well we’ll just tell them not to bring their children” strategies combine a liberal squeamishness over discussing immigration in general, with a fear that saying anything out loud might trigger a hostile immigration intervention both locally and nationally.

The assumption seems to be that identifying and discussing the problems that a group of students are facing will lead to a crackdown on those students rather than action on the problem and help for those students.

But whether you depend on the money that international students bring in, or are keen to understand how to support people regardless of their economic contribution, the sector can’t just assume that the things it did to support the participation of students from China will work for everywhere and everyone else.

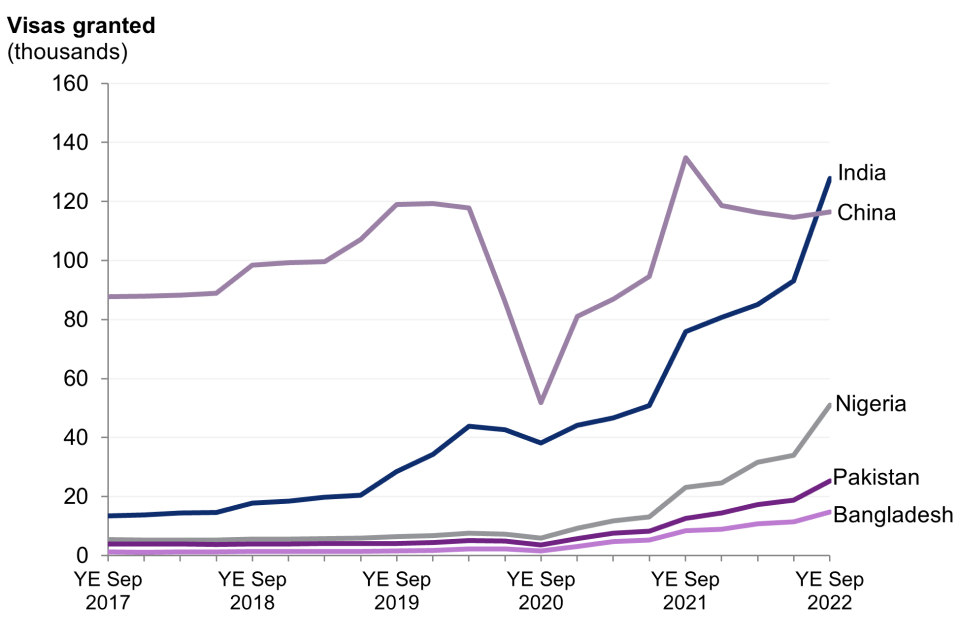

Earlier on Wonk Corner, Jim dug into the figures to identify issues with expansion pace and dependants from different countries. Here we try to explain what’s been driving a tenfold increase since Q3 2020 in visas issued to Nigerian students specifically.

Pray for better days

In the latest figures from the Home Office, it is India that has now overtaken China as the top country for sponsored study visas – but graphs like this smooth the figures and to some extent hide the extraordinary increase that we’ve seen from Nigeria:

In the third quarter of 2020, the Home Office issued just 5,914 student visas to people from Nigeria. A year later that figure rose to 22,288 – and this summer the quarter preceding the start of the academic year hit 56,661.

This year, 65,929 Nigerians were granted sponsored student visas in the first six months alone! This is the highest ever recorded in 4 years.👀

Read the full story here: https://t.co/CH97IKLLwo#Dataphyte #DataforDevelopment pic.twitter.com/ZAgXTtmFUI

— Dataphyte (@Dataphyte) September 14, 2022

On the face of it this is great news. If you’re confident that a particular department, university or the sector in general can cope with rapid expansion, or you are content that the right regulatory tools in both the Home Office CAS issuance system – and the particular UK nation education regulatory system is assessing what is principally PGT expansion effectively for quality – then brilliant. This can definitely be viewed as representing something that the International Education Strategy and its recent update was aiming at achieving.

It also helps plug the funding gaps that a freeze on home domiciled fees and an energy and inflation crisis are generating. Yet there seems to be more to the picture.

Specifically, the offer of the “graduate route” visa offering two years (or three years for PGRs) work as one of the “points-based system” reforms is assumed to be the driver of the expansion – and there’s little doubt that that is acting as a major pull.

But is there a pent-up push we’re not seeing?

Japa japa, japa lo London

Yoruba is one of the three largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, concentrated in the southwestern part of that country – and “Japa” combines two Yoruban words – “Ja” which means “to run”, and “Pa” which tends to be used to exaggerate verbs. Thought to have its origins in a 2018 Naira Marley song of the same name, in colloquial use, it’s best understood both as a push and a pull – fleeing, running away or escaping from somewhere, and making a better life and future for yourself and your family elsewhere.

It’s pretty much a cultural phenomenon. Articles on its origins and impacts are everywhere if you Google search them. You can find entire TikTok subcommunities devoted to it, there are documentary series like this on its impacts, and endless sources of top tips and cautionary tales for those thinking of taking the plunge.

That push factor makes some sense. Nigeria is facing its own cost of living crisis – recent figures had inflation up at 20.7 per cent with a huge 42 per cent youth unemployment rate. Even where young people are employed, companies across the country have been reporting high resignation rates – and scores of businesses have appeared to support those looking to emigrate with both intel, visa and university application advice, and short-term loan financing.

“When people are trapped in a system that offers no hope for the future, life loses its meaning so they migrate to favourable climes,” says Enang Ebingha, a specialist in population studies and professor at the University of Calabar in this piece on African Arguments. He’s worried about the workforce in Nigeria depleting as key industries in the country experience a brain drain – but there’s little sign that the government can or will do much to arrest what’s being called the “Japa wave.”

And in this piece, Ayodamola Oluwatoyin, the Programme Director of Reform Education Nigeria, tells University World News that most people see fleeing the country as a way of surviving:

Most of the policies of the government itself are anti-youth; the government has made the economy difficult for youths to thrive. Most people are still going to leave, and to be honest, it is very sad.”

That sounds familiar.

Owo tollgate yen

Francisca Chiedu, a Nigerian master’s student at Robert Gordon University who became President of the SU back in 2012, notes here that in August organisations in Nigeria witnessed “mass resignations” because of employees relocating to the UK for postgraduate study:

Immigration has become a product for Universities, the Home Office, School Agents, Banks, and all other parts of the student visa value chain. International Students are cash cows, the product is designed such that you can meet the initial requirement, come in, and pay small-small. So for most people coming here, you are simply coming to work and pay school fees with the hope that you will secure a permanent job that will give you a Tier 2 sponsorship visa. After five years of working on a Tier 2 visa, you are eligible for Indefinite Leave to Remain in the UK, popularly called ILR. So, in short, for most “Japarians”, the goal is ILR. The ILR is permanent residence status.”

That is an assumption about the purpose of coming to study in the UK that upsets the idealised applecart of what we think an international student “is” – which in aggregate tends to be someone who will prop up our higher education economy, maybe stay for some work experience on the graduate route and then leave – importing back our “values” in the process.

But that may not be what is happening here.

As well as the tales of makeshift creches on campus and families trapped in Airbnbs several weeks into the academic year, many are muttering quietly about students dropping out – as evidence emerges that students are applying for and getting employment offers in our beleaguered care sector.

Still hope and pray for better days

Changes to the skilled worker visa system mean that applicants are no longer required to hold a degree level qualification to apply – and if a student secures a job offer from an employer approved by the Home Office, they can switch from the student route visa to the skilled worker visa immediately, without having to complete their degree.

As PIE News notes in its piece here, there seems to be a “growing trend” of immigration consultants and agents using universities as a “stepping stone” to help clients enter the UK and switch to care jobs before they pay fees in full:

This route offers a cheaper and faster pathway to full-time employment in the UK compared to the graduate route – which requires students to pay expensive course fees and maintenance for the duration of their course, before entering the jobs market. While this is a completely legitimate immigration pathway, it will play havoc with university finances as it cannabalises the international student population before they graduate.

And the piece argues that the sector’s tendency to look internally for answers over increasing drop-out rates may have missed the most obvious factor:

Very few will have identified the ease that students can move to full-time employment so soon into their university life.”

As well as endless Japa-to-the-UK YouTube videos on applying to university, finding family accommodation and getting part-time work, there are plenty of guides to getting jobs in the healthcare sector – which in other contexts we seem to be desperate for people to do given the backlogs now being reported on daily in the NHS.

But even for those not intending to enact this kind of switch who are intending to specifically learn and study, Chiedu has a warning for those “planning to Japa”:

I think many people are misguided about the courses on offer. When I have some time, I will share my thoughts on misinformation about some courses and unfulfilled promises made by some Universities just to attract students. It is insane! I am sorry, but many of you will be disappointed, especially those doing Business courses. Some schools charge over £20K for internships and end up not offering them. This is misleading. You see all those courses they call “international this and that, and those with long bogus titles? Most marketing departments of Universities just coin fancy course titles just to attract students, but today is not the day to “break that table”.

I ain’t going to that station

Chiedu’s warning is perhaps the most interesting thing about the situation. For all the sound and fury over the ONS net migration stats release and the balloon floats from Number 10, the UK would be unlikely to actually act in the way that Suella Braverman has been suggesting – party because it would crash several universities and the opportunities they offer, and partly because doing so would cut off what amounts to an essential way of masking required economic migration to the UK in a context of a million vacancies in the economy.

If the country wasn’t so hopelessly divided into knee-jerking camps over immigration, we could start to have a sensible conversation about what’s really going on, whether that’s in the interests of the UK and the countries it recruits from, and what the real needs of students and their families are that we ought to invest in. Even better, we could design a sensible bespoke immigration route that combines higher level skills and study with entry into the kinds of professions where we’re short of people.

As it stands it feels like the sector is running the risk of taking the money while ignoring the needs, and convincing itself that it is selling education tourism when students think they are buying economic migration. If students are right and huge numbers stay, the press will vilify them and the sector. If the sector is right and a crackdown is coming that might remove the graduate route (at least for dependants), they’re being mis-sold having borrowed the money to buy. We need a way out of that paradox, sharpish.

“But one thing we keep coming across is a deep desire to avoid even talking about these things on campus.” Unsurprising, especially if comments such as: “Universities here might not think that they’re selling economic migration – but that is what we think we are buying.” are to be kept from the general public’s awareness so they don’t try and derail the universities gravy-train.