When you’re first in your family to go to university, you tend to get your information on being a student from popular culture – and the 80s movie that got me interested in university was the 1985 Val Kilmer campus cult classic Real Genius.

Early on in the film there’s a montage in which “genius” high school student Mitch Taylor is shown getting to grips with becoming a student – carrying piles of books, trying to find a room on campus, spending time in the lab, that sort of thing – and there’s three little shots of him attending lectures.

In the first during welcome week, the room is packed out with students taking handwritten notes. In the second, a number of chairs have ghettoblasters on them rather than students, recording the lecture. Next we see a little device that the student who becomes his love interest has invented to automate turning the pages of a book so they can cram while tired.

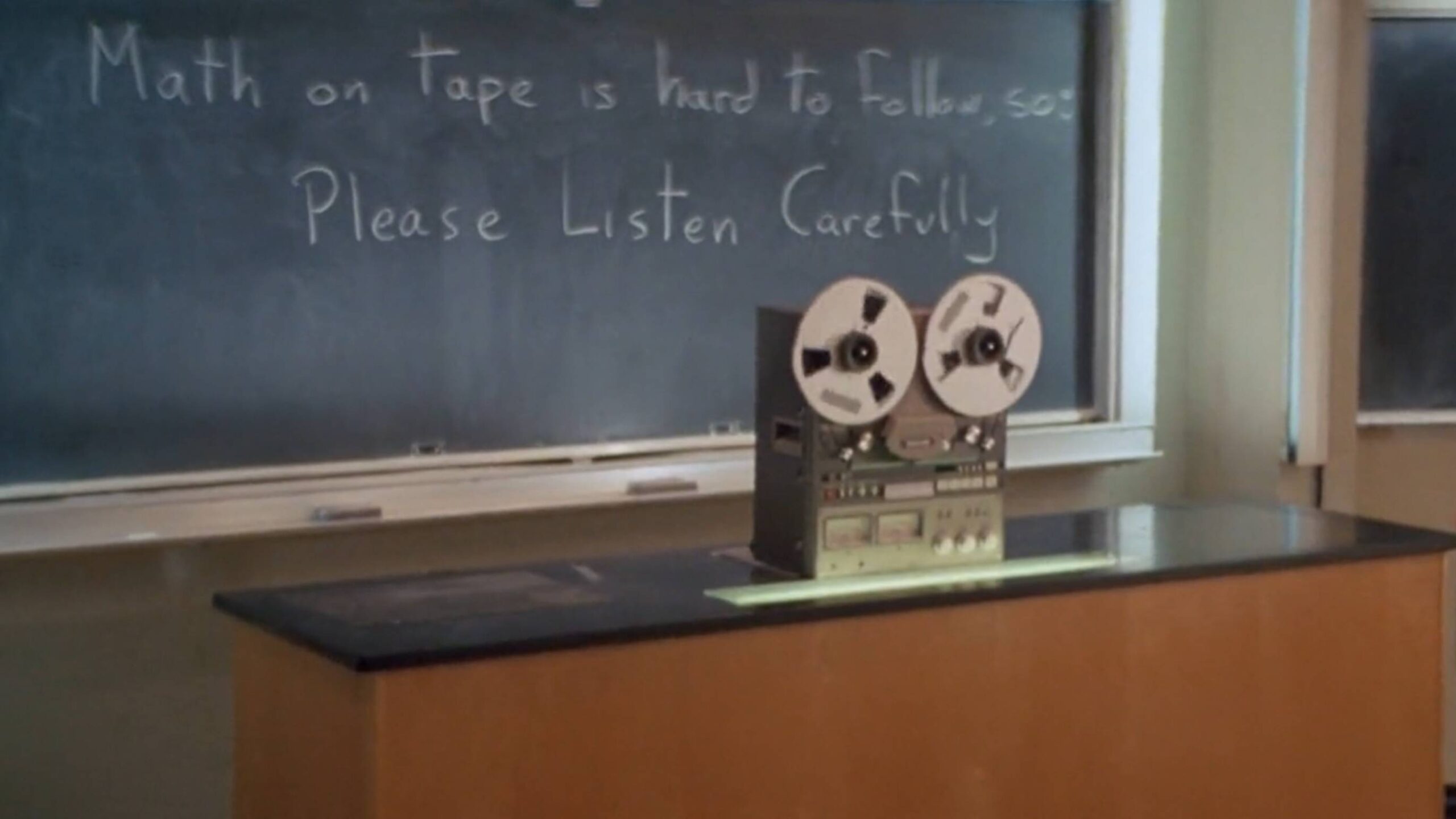

By the third and final lecture shot at the end of the semester, young Mitch walks in to find no students present at the lecture at all – and no lecturer either. “Math on tape is hard to follow – so please listen carefully”, says the legend on the blackboard.

Welcome to your life

I don’t know if that ever actually happened in an actual university – but I was reminded of it when I saw Sheffield Hallam psychology lecturer Peter Olusoga’s viral thread on empty teaching rooms:

Dearest Students,

I don’t want to hear a single word of complaint from you EVER, about ANYTHING. #AcademicTwitter#AcademicChatter pic.twitter.com/Gjnt7nO45F

— Dr Peter Olusoga (@PeteOlusoga) November 29, 2022

Given that using technology to enable students to ditch in-person attendance towards the end of the semester is hardly a new thing, the question is whether the problem has gotten worse – and what it tells us about how higher education might be delivered in the future.

Action research from a 2022 Solutionpath project found that early intervention improves engagement. Teesside University found that the earlier the initial intervention is made with a low engaged or unengaged student, the less likely the student is to withdraw at any point in their course. University College Birmingham found that early engagement and attendance were significant predictors of later retention, attainment, and engagement. The University of West England suggests that an earlier period of engagement is even more sensitive and disengagement students were then more likely to continue to be non-engaged in semester two.

So given many of our current third year undergraduates students will have spent the early years of their university career with little to no face to face engagement, is it any wonder that engagement remains low?

And then there’s mental health. The scarring impacts on the young of Covid haven’t really reduced – half report high anxiety, one in five are lonely often or always, 22.2 per cent have a “probable mental disorder” and there are clear links between mental health and finance. That doesn’t feel like a recipe for high non-compulsory attendance.

There’s no turning back

In the thread, there are lots of other theories both from Olusoga and those contributing and commenting. Some put it down to fees and students seeing themselves as “customers” – although it’s not at all clear to me that people are more likely to use things just because they get them for free.

Some blame marketisation and the framing of universities as job factories – although both Mitch Taylor and Kilmer’s character Chris Knight seem perfectly capable of being passionate about their subject and desperate for a job afterwards all at the same time.

Olusuga himself wonders whether motivations for undertaking a degree have drifted away from a “genuine desire” to study a subject, and more towards “just the thing that you do after school”. But was there ever a time when the majority of those who went to university hadn’t had it framed as an extension of the educational conveyor belt?

Thinking about the investment students are making, Olusoga also said that not turning up to a lecture is like “setting fire to a £20 note”. But the cost of getting to campus, childcare, or turning down paid work is often much more than £20 – especially if you can do the work, look after the children, avoid the bus fare and then access the lecture online afterwards.

Some argued that in the “neoliberal” university, students are bound only to engage in activities that appear to relate directly to getting grades or those leading to employment, rather than passion for the subject. So many of those takes sound like they’re railing against the right, but eventually end up sounding sniffy about massification and its tendency to take in those who worry more about their economic future than the average entrant did in 1985.

I don’t want to sound excessively dismissive of any of those arguments – and for what it’s worth, I don’t see any real evidence that it’s about teachers or the teaching per se. But I do think the answer is right under our nose – and I think it relates to the contemporary reality of students’ mode.

Even while we sleep

The common and accepted understanding in the sector is that over the past decade, there has been a collapse in part-time study. In addition elsewhere on the site our own David Kernohan notes the gap in our understanding of why people choose to study part-time, of applicant and student views, or of how the government could help make it easier for them.

But a closer look at the actual numbers suggests that the story may not be that simple. It is true that part time undergraduates have pretty much halved from circa 150k in 2010. But “full-time” mature undergrads are up 40 per cent over the period – and that’s without taking into account the impacts of “depletion” of mature demand because of increasing entry at age 18. Perhaps a huge chunk of those lost part-time students switched to full-time.

Or maybe, more likely, students are all part-time students these days.

In this year’s HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey, 77 per cent of students worked during term-time to supplement their living costs, and 1 in 5 said they were working to provide financial support to friends or family. No wonder in late October 3 in 10 were skipping non-mandatory lectures or tutorials to save on costs. That won’t have got better as the term progressed.

Just a week or so ago IFS told us that a failure to uprate student financial support for inflation means that the lowest-income students are £1,500 worse off in real terms – that’s over 5 hours a week extra work required on the minimum wage. And there’s strong demand for that labour. It can’t be a coincidence that a large group of international student sabbatical officers is preparing to launch a campaign to increase the numbers of hours that international students can work up from 20 hours.

The other day, ONS told us that 63 per cent of financially comfortable students are satisfied with the academic experience when compared with 21 per cent of those facing major financial difficulties – with a less pronounced but significant difference on social experience too. We don’t have qual for those findings, but poorer students don’t rate teaching differently – they’re just more likely to miss out on it.

Rent hikes and housing shortages (especially for those with dependants) mean that students are living further away from campus than ever – and getting to campus is getting more and more difficult too. Britain’s rail network is broken, there’s a huge and largely unreported vacancy rate amongst bus drivers causing constant cancellations and intolerable delays across multiple cities, and we definitely don’t want them bringing cars.

So maybe the tech has made it possible to not come to campus, and the context means that most students haven’t got the time for anything the compulsory or essential – all interacting with campuses, timetables and support services that are almost all designed for full-time immersion.

Acting on your best behaviour

In multiple university towns and cities right now, the sector is cruising towards a housing crunch that now can’t be solved. The supply of rooms that are of an appropriate standard, distance from campus and price just won’t be there – and there are almost no incentives to working that out and warning students in time.

Once we accept that, we end up with unpalatable choices. One option is to create the kind of dorms that students share in Real Genius – but we really aren’t used to having two students bunk up in the UK, and much of the contemporary stock wouldn’t suit that anyway.

Another might be to find ways for one of the three undergraduate years to be away from the city – which appears to be happening anyway for lots of final year UGs, who deserve their experience to be supported and normalised rather than lamented as a marker of poverty.

We could seek to hurl money at students to bridge the widening gap between statutory support and the costs of hanging around on campus all day. But with the unit of resource dwindling, that will get harder and harder to do – especially when the political pressure will be to maintain the illusion of opportunity while blaming universities when the poorest inevitably drop out or disengage.

But those options, and others like them, are all about reaching for ever more fanciful ways of attaining the full-time student dream – that many of us had in our youth – that may now simply be unattainable for large numbers of students.

This is difficult to talk about – the student finance rules for home domiciled students claiming maintenance loans force us into pretending the problem isn’t there, and the immigration rules have a similar chilling effect on addressing the issue head-on. But we may have to accept, assume and plan for them all being part-time now.

This isn’t some long-term project – in fact thinking the unthinkable, saying those things out loud and acting is where we might have to go very soon. And so here’s a few suggestions for making what we might call the new “part time full time” mode work.

Turn your back on Mother Nature

First – online isn’t *the* answer. Of course making some things available online helps. But taking a part-time student experience that is spread over a full-time week and making it available via a phone doesn’t really improve that experience. It’s crucial to stop thinking about the hours of teaching that are delivered in isolation to the rest of the experience.

We should try to ensure that we know more about the lives of our students both on entry and during the academic year. Nowhere near enough of the contributions to Olusoga’s thread suggest that students have been asked. Pre-arrival research for the former and reimagined rep roles for the latter will all help – as will shifting from asking students about teaching or the university to asking them about their learning. Considering carefully, explicitly (and collaboratively with students) the appropriate line between attendance expectations and flexibility in this stretched age will also help.

As a thought experiment, entire schools and departments should get heads together with students and professional services colleagues to imagine how the course and the campus could work if it was only allowed to be open for two days. Timetabling intensity, with support and extracurriculars that fit around it, is almost certainly going to be a better bet in coming years than 15 hours of increasingly optional encounters spread thinly over five days.

Next we should work especially hard on reasons to come to campus that address the problems. I hardly ever see anywhere to take a proper nap on campus, social learning spaces resemble airports you want to leave rather than cosy common rooms you want to stay in, and few universities have really put their back into increasing employment opportunities on campus. Yes – in some cases doing so will reduce the consistency and quality of some professional services. It’s worth it.

In the classroom, it appears from the block teaching experiments that are on around the UK that they allow quite rich, “school uniform” style all-on-the-same level immersion for short bursts of time while the diversity of the study body then does its different thing in between- as well as dealing properly with that deadline bunching thing. That’s surely more desirable than the “4 modules at once” default that generates the kind of deadline bunching that will all but destroy in-person engagement at this time of year.

When Essex Art History lecturer Matt Lodder asked the other day how cults got their students to become so engaged in the course material, I instantly thought “block residential teaching”. Many of us have had intense and rewarding experiences on residential training events – and settling for that intensity of the “part time” full-time experience may be better than spreading it as thinly as we do now. Accommodation arrangements to support it would be great too.

Everybody wants to rule the world

In Real Genius, when Mitch and Chris aren’t in the lecture theatre, they’re engaging in high jinks, foam parties and edgy pranks that paint a picture of deep immersion in the student experience that generates the kind of engagement, creativity and passion in students that many are worried is now missing.

They make scientific discoveries. They get one over on their corrupt tutor. They invent gadgets. They drink. They fall in love. They learn.

For me, those that bemoan the students of today for not engaging in that way or for “only doing the minimum” miss the point. It’s not that students don’t want that stuff – it’s that the kind of immersion on offer in the movies and in our memories may now be utterly unattainable for them. It’s an especially pernicious kind of mis-selling.

But we are where we are. If I’m right – and almost all students are part-time these days – the least we can do is structure those bursts of engagement in ways that are purposefully designed to be social, transformational, intense, and as magical as the first time I saw the laserbeam explode the popcorn in Jerry Hathaway’s house.

This goes hand-in-hand with the part-time degree commentary from a few days ago. If we expanded the provision of part-time study we would widen access but also potentially change the deepening attendance issues. I actually elected to study my final year part-time over 3 years which allowed me to work around my degree.

We could have some sort of employer charter in a similar manner to how employers sign up to allow staff time off around training and serving in the reserves.

I’ve been seeing some commentary on (anti) social media about this, some are claiming its because students need to work to earn enough to live, some possibly, but all? Of course the cold weather means the attraction of staying in a warm bed rather than facing the day and cold wins out for many, as well as the convenience of recorded lectures that can be viewed anytime, one of the legacies of covid remote learning. Some lecturers however are rightly questioning the record for later delivery move in many universities, suspecting their lectures will be reused many times over into… Read more »

I find the fact there has been so much discussion and hand-wringing about this baffling. It was a 9am lecture near the end of term, they’ve always been poorly attended. I would bet my house that the assessment for that module lets you choose topics in a way that you can realise when you’ve either covered what you’re going to do in your coursework or got enough topics for the exam, and that that point comes before the end of term. Twelve years ago I took over a module that was designed so you could write all the coursework on… Read more »

Jim I love the article, but I’m not sure that your claim that your claim about the number of students in paid employment is correct “In this year’s HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey, 77 per cent of students worked during term-time to supplement their living costs…” I think that the SAES states that, of the students working, 77% are doing so to support their living costs (page 55) I don’t think that there’s an actual number for the students working, but it appears that around 9% of all students’ income is derived from paid employment (probably a significant proportion… Read more »

A lot of this is golden-ageism, and studies have been going back to the 1980s (see Galichon and Friedman, 1985). I myself did a piece of qualitative work into it, back in 2015 exploring qualitative reasons for non-attendance. Within that work, which reflected upon what was then perceived to be a ‘crisis point’ in attendance (largely built around early lecture recording fears). A core finding was that students weren’t there because they just didn’t feel that they needed to be there. Most knew that it would be better for them academically if they did attend all classes but knew that… Read more »

One way to cut the pressures on students’ costs and on their accommodation is for students to commute to university from their parents’ home, as 84% do in Australia and around half do in Canada and the USA. This would change students’ higher education experiences and the higher education market (Norton, 2020). It may also risk UK universities’ enviably high graduation rate.

Norton, Andrew (2020, November 30) Key differences between Australian and British higher education: regional versus national markets and institutions

https://andrewnorton.net.au/2020/11/30/key-differences-between-australian-and-british-higher-education-regional-versus-national-markets-and-institutions/