When describing the strengths of UK higher education, international collaboration usually features highly.

One area that merits further development, though, is where widening access is concerned. The challenges here are seen as intensely local, and the pressures exerted by successions of policymakers on making outreach “more effective” has left little room for the kind of cross-border linkages that characterise much of the rest of the sector. However, if indeed widening access work is going to be more effective, then this needs to change.

Mobilising access efforts

Today is the first World Access to Higher Education Day. The aim of WAHED is to mobilise national and international efforts and act as a catalyst to address inequalities in access and success in HE across the world. Inequality in access to HE is a global constant. In every country where there is evidence (over 90%), access to HE is unequal by social background.

These inequalities are being addressed in innovative ways across the world. The Education Development Unit in the Faculty of Commerce at the University of Cape Town in South Africa has reduced drop-out rates among black students by over 50%. The Education Opportunity Programme (EOP) at the University of Berkeley has reduced student drop out rates to less than 3% in a country where it runs at 30%.

The common bond that links these two programmes is that they work with specific groups of students through their HE career rather than relying on delivering an inclusive curriculum for all students. Innovative approaches from other countries show that it is possible to target students from low-income backgrounds in HE without as is feared often in this country stigmatising these students, but using their identity as a strength.

Over 100 organisations across the world are involved in WAHED and there will be activities in over 30 countries. Many of these activities though will be focused on raising awareness regarding inequalities in access and success.

New research launched for WAHED shows that the policy commitments to addressing these inequalities across the world are weak in the majority of countries.

“All around the world – Higher education equity policies across the globe” is the largest global survey to date on looking at policy commitments to equitable access to HE covering over 70 countries. It finds that, while achieving equity is a headline priority for governments on the whole, policy commitments vary considerably from country to country. This suggests that several are only paying lip service to the equity agenda.

Policy commitments vary

The report shows that only 11% of countries have a comprehensive national equity strategy which covers a range of under-represented groups. Less than a third have defined specific participation targets for any under-represented group of students. UK nations fare well with all considered to be in the top tier where policy commitment is concerned, although England does not have a widening access strategy. The report classifies countries in four different categories in terms of policy commitment. England and Scotland are two of only five countries in the advanced category alongside Australia, Cuba and New Zealand.

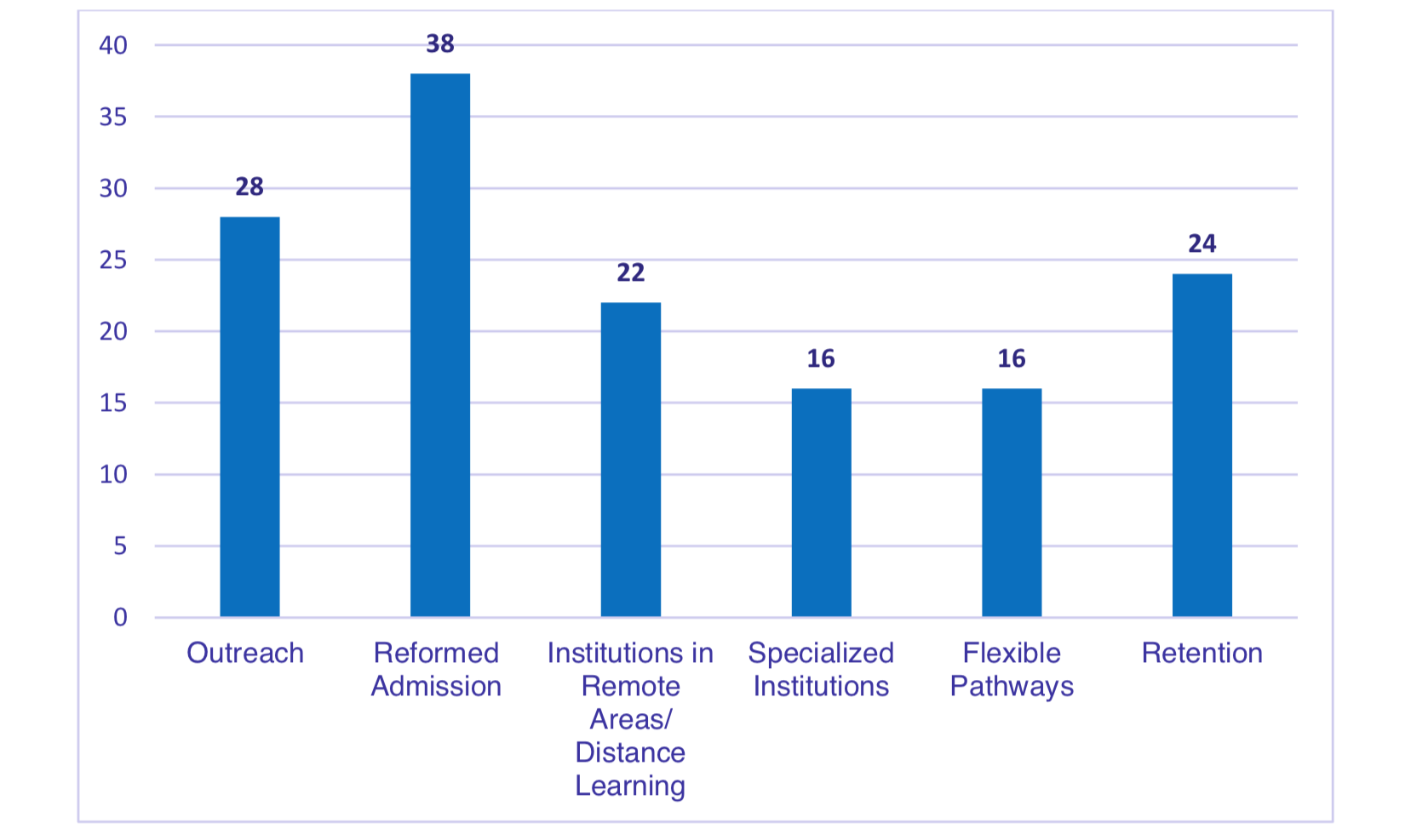

Another interesting finding is that many countries’ definition of equity revolves heavily around financial instruments to aid access, rather than non-monetary measures, with a widespread tendency to look at barriers to entry rather than to promote interventions to boost the chances of success. Among non-monetary programmes, however, the most commonly used are: affirmative action, reformed admissions criteria, and outreach programmes.

Figure 1: Frequency of non-monetary measures

Source: All around the world – Higher education equity policies across the globe – Jamil Salmi, Lumina Foundation, World Access to Higher Education Day

The case for greater, systematic collaboration in this area rests not just on what we can learn from others then but what we can offer. In the post Brexit world, internationalisation for UK HE may require us to look for different areas of global leadership, steeped perhaps in a greater degree of humility. Widening access would be a good place to start.