Each quarter when the Home Office’s immigration stats appear, I’m often implored to not assume that any extrapolated trend will play out.

That has been especially true when Q1 and Q2 figures appear – on the basis that it’s somehow dangerous or scaremongering to assume that YOY increases in these quarters will somehow signal huge increases in the Q3 and Q4 bulges that drive September and January intakes.

In some cases, plenty of folk just think that there surely has to be a limit – that at some point demand will level off from the new markets that UK is ploughing, or that the lack of campus or community infrastructure will just cause the sector to become “full”.

Those warnings may well be true for this latest round of stats from the Home Office, which tell us about study visa issuance for April, May and June 2023. Then again, they may not.

We’re going up, up, up, up, uuuuup

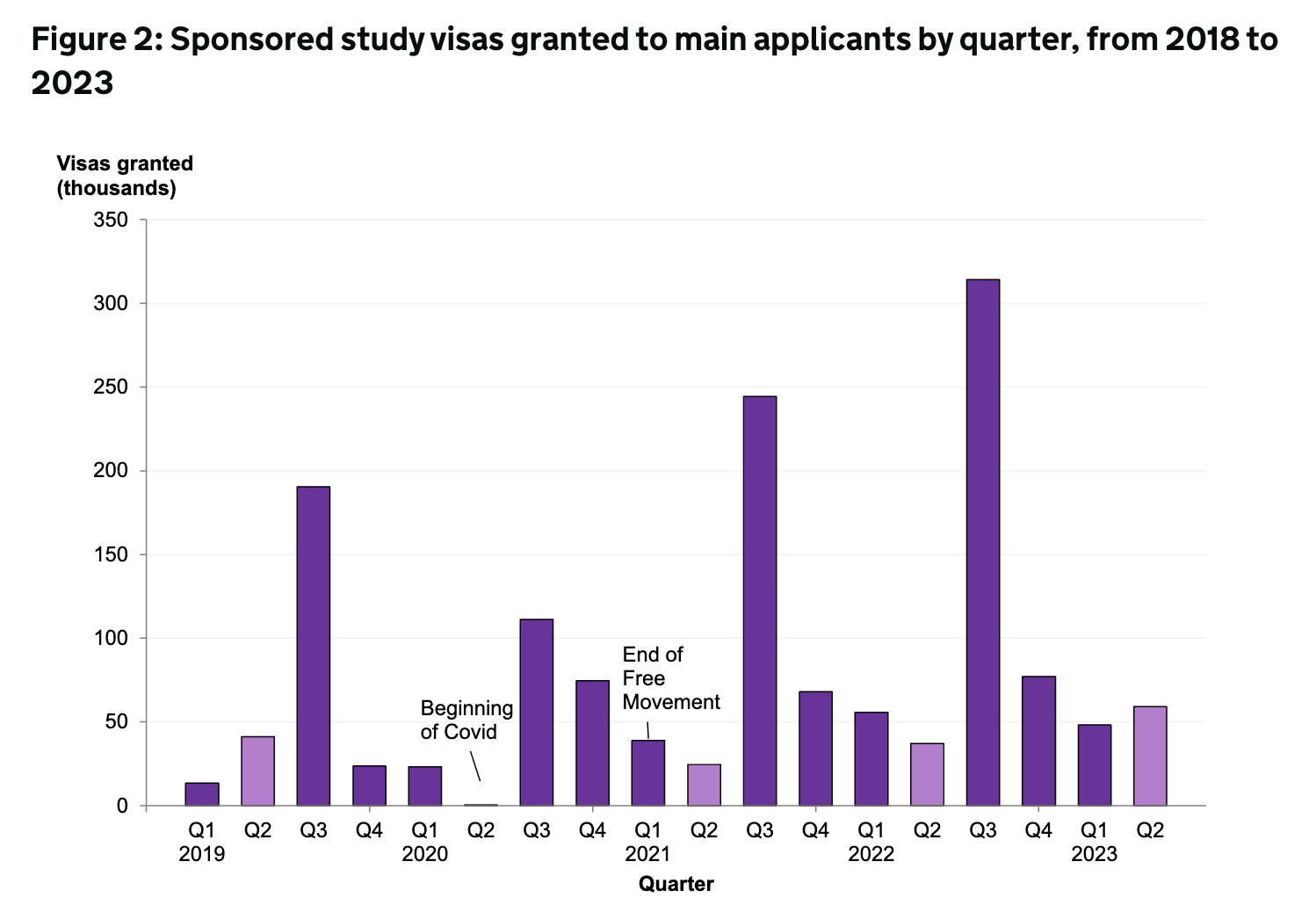

On the face of it, it’s another startling increase. Study visas issued in the quarter rose from 31,674 in Q2 2022 to 46,355 this year – a whopping 46 per cent increase YOY.

The hopium and copium for those worried about how that will look this time around tends to focus on the idea of students applying earlier, or getting in ahead of further restrictions. But experience over the past few years tells us that might just be another extrapolation of the trend.

The simplest thing to do is just look at the angle of the increases each quarter, and then have a guess at what the pre-September Q3 figures will be. That would put the quarter we’re in now on about 400k – another record – and a huge contributor to what will then become the net migration story when those figures are next done.

Because as I often say – when you’re on the ramp up before you level off, arguments emphasising that students eventually leave are irrelevant.

Even if you view international students as a kind of educational tourism, and even if your increases since 2018 are all in one year PGTs with no graduate route take up, if your sector goes from steady state circa 200k visas issued in 2018 Q2,3 & 4 + 2019 Q1 to over 450k four years later, that’s still 250k’s worth of bedspaces, study spaces, personal tutors, local buses, core texts and so on.

And unless you can prove you’ve now stopped growing, politicians will justifiability end up alarmed if aspects of all of that are starting to feel stretched.

Country by country

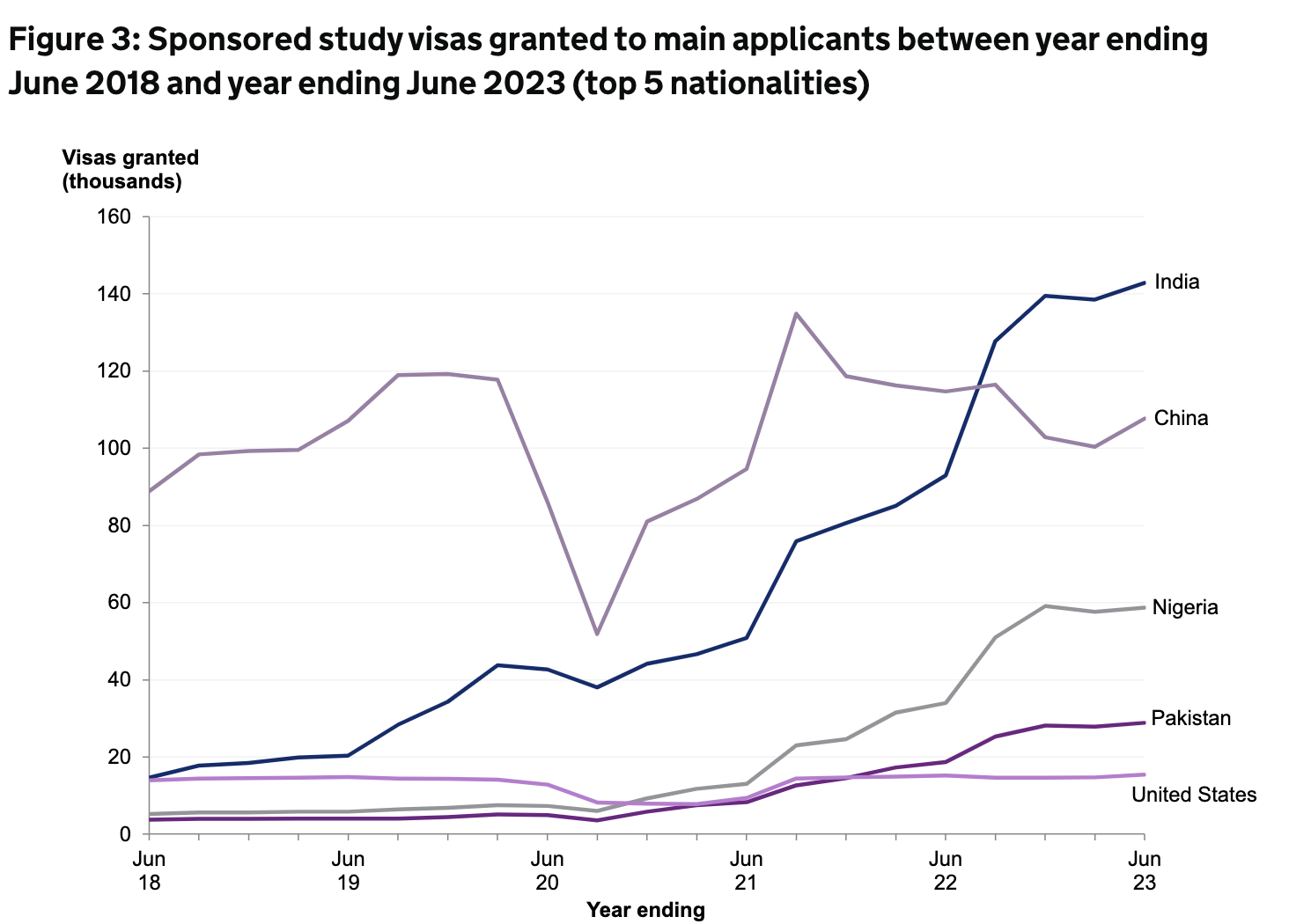

In country terms, the stats do raise some trend questions. Do the year on year stuff and we see 142,848 sponsored study visa grants to Indian nationals in year ending June 2023, an increase of 49,883 (+54 per cent) compared to the year ending June 2022, and the largest number of study visas granted to any nationality. Grants to study for Indian nationals have risen markedly since year ending June 2019 and are now around 7 times higher.

Chinese nationals were the second most common nationality granted sponsored study visas in year ending June 2023, with 107,670 visas grants, 6 per cent fewer than the 114,680 in year ending June 2022. Chinese and Indian nationals together comprised half (50 per cent) of all sponsored study grants.

Of the top 5 nationalities granted sponsored study visas, Nigerian nationals saw the largest percentage increase, up 73 per cent from 33,958 in year ending June 2022 to 58,680 in year ending June 2023.

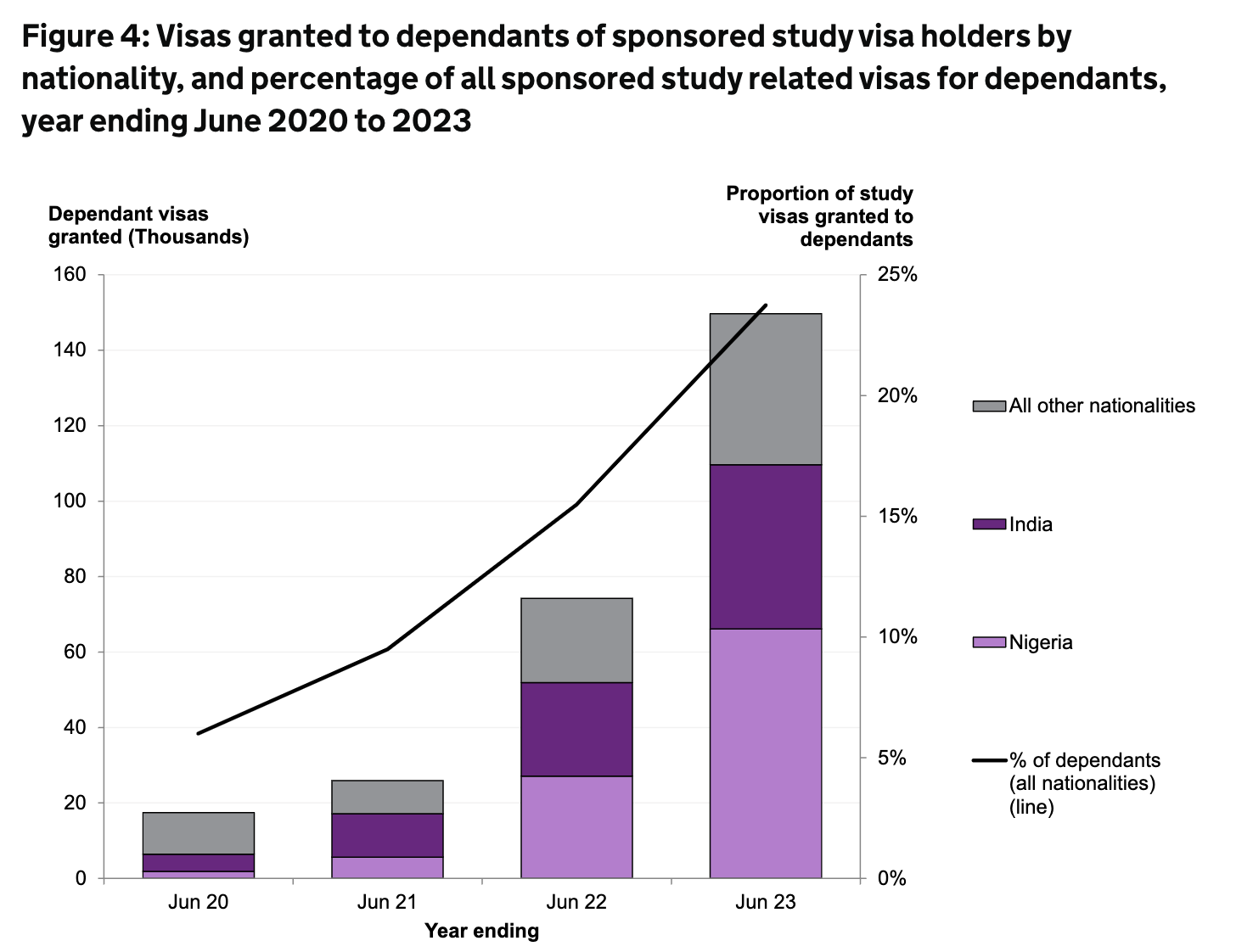

The government will be hoping that the January 2024 dependant ban tempers that figure – here we see a continued trend in dependant rises both in volume terms and proportion terms – a story we’ve noted on the site before.

We never get told the level of the course applied to in these numbers, but for some reason we are given a Russell Group / Non RG split – that shows that RG visas issued has gone up by about 50 per cent in four years, whereas in the rest of the sector, it’s tripled. That will play into the usual prejudices and narratives that we see in the media and politicians’ utterances.

Helping to drive the demand – or depending on your POV, adding to pressures on wider community infrastructure – is the graduate route. 119,816 extensions were granted in the in the year ending June 2023 in the Graduate category, an increase of 80 per cent on the previous year.

Indian nationals accounted for over two-fifths (42 per cent) of grants in the Graduate route in the year ending June 2023, and additional analysis Migrant Journey data shows that 20 per cent of students whose leave expired in 2022 switched to the Graduate route following their studies.

We do what we want and we do it with pride

All of which brings us back to limits. It is simply impossible to believe that the higher education “system” (and I’m counting all the grown ups here) put in place the educational, support and physical infrastructure to properly support these volumes of increases back in 2019, let alone ensured that wider community infrastructure was able to support it.

That will, if the sector carries on the way it is, lead to nasty, kneejerk responses of the ilk we’ve seen in previous months – and so the strategic question is who should impose (further) limits – the Home Office, or the education regulators, or universities themselves.

In England the Office for Students (OfS) has thus far proved itself to be completely incapable of testing the extent to which numbers growth exceeds meaningful capacity, universities seem to continue to (need to) grow seemingly without reference to capacity, and the Home Office’s solutions are too simplistic. Hard number controls wouldn’t help either, especially with the distribution issue.

But without limits, we repeatedly shift from what ought to be basic minimum rights (the number of desks on a campus to study at, the number of bed spaces at a reasonable price within easy reach of campus) to aspirations – and that simply isn’t acceptable to any student, home or international.

Techno techno techno techno

So here’s what I would do if I was an incoming Labour minister. Universities always assert they plan these things – so I’d call universities on it. I would ask the regulator to cause each university to set itself a “meaningful capacity limit”, campus by campus, subject area by subject area, for students in full-time attendance (breaking out UG and PGT) at that university.

It would have to reference subject area diversity, an analysis of likely mix of “away from home” and commuter students, analyse community infrastructure (ie types of bed spaces at different price points) as well as campus infrastructure (including SSRs for PGTs at subject level) – and do so in collaboration with other universities in a given area.

Universities would publish it so stakeholders could test the assumptions, get it approved by the regulator, and if it therefore meant that (for example) over a certain number of students would mean going below an SSR of X for Business Studies in PGT they would stop recruiting as per their plan.

This would, of course, require the regulator to stop pretending that a focus on outcomes and satisfaction with outputs can replace an actual look at hard inputs and outputs altogether. It will have to, eventually.

This meaningful capacity analysis regime would protect autonomy, force consistent and transparent thinking in capacity planning, and surface important information that would help students choose. And it would mean that instead of feeling forced to recruit ever more international students to balance the books, universities would be saying to government – we’re now full. Now you need to fund us.

The alternative is situations like this, as usually-unfailingly friendly Canada considers a hard and blunt cap. Amid widespread reports of acute shortages and rent rises, its new housing minister Sean Fraser told reporters this week:

We’ve got temporary immigration programs that were never designed to see such explosive growth in such a short period of time.

Ditto.

It’s interesting to note from the Migrant Journey data that the majority of Indian and Nigerian students stay after their studies, most commonly on either graduate visa or skilled worker/skilled worker (health and care) visas. It’s too early to tell how many people on graduate visas will end up staying in the country long term though.

Perhaps a good thing, given we need immigration anyway and this means recruiting young, English speaking graduates. But it is clearly going to make a huge contribution to the housing requirements, particularly in areas surrounding universities.