The Office for Students (OfS) has published its “statement of expectations” outlining the practical steps that providers should be taking to tackle harassment and sexual misconduct – including harassment based on age, disability, gender reassignment, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation.

We won’t go over this again here, but it’s been a long time coming – and now emerges in the wake of weeks of press coverage surrounding Everyone’s Invited, which reached its disturbing zenith when someone from ITV created a league table of university disclosures on the site.

The outputs here are a number of sensible tweaks to the “statement of expectations” we last saw in January 2020, and a blog from OfS CEO Nicola Dandridge exhorting all providers to review their policies, systems and procedures before the next academic year.

The Sun told us that Gavin Williamson had ordered both a “crackdown” and a “clampdown” into university rape culture, but as predicted what that really means is the realisation of OfS’ promise that it would “fast track” formal publication of the the draft statement it paused consultation on last year.

As such it’s not quite the “crackdown” or indeed the “clampdown” promised – but a press release headline that says “review sexual misconduct and harassment policies by this summer, OfS urges universities” will be enough to convince the press even if there aren’t any real penalties if providers just ignore the urging.

And having spent decades trying to get universities to deal with cases rather than palm them off on the police, those that were spooked by pre-briefing in the press that the government wanted to see universities involving the police when serious crimes such as revenge porn and harassment may have been committed “rather than dealing with such cases internally” will be pleased to learn that that line is nowhere near the OfS stuff, nor DfE’s covering press note.

Stating the not so obvious

Let’s look first at what’s changed since we last saw the expectations statement just over a year ago:

- In whole provider approach, senior commitment now should be both visible and ongoing, presumably reflecting some feedback that this stuff tends to come in bursts but requires sustained effort.

- For some reason the previous version’s exhortation that standards of conduct be communicated to both prospective and current students is now just students, which feels like a bit of a missed opportunity.

- New in this version is that communications be adapted to different groups which we assume is a nod to cultural sensitivities, but feels like it needs further development.

- Making clear conduct expectations has now moved from being something that should be communicated as part of induction to something that should both happen then and on an ongoing basis, which makes sense.

- In the section on governance, providers are advised that they could, for example, look at prevalence data rather than just case data.

- Where providers are engaging with students they are now nudged to involve those who’ve previously reported as well as those who’ve been involved in investigations, and nudged to have a think about mode and students with protected characteristics when doing so.

- In the section on training a new bit suggests that it’s regularly reviewed, and for some reason should consider bystander initiatives, consent and receiving and handling disclosures is now just may include (which may well be because ministers have branded bystander initiatives on racism as a sinister assault on free speech).

- There’s a new bit on being clear with students about what happens when an anonymous report is made.

- And there’s a line in there now on using appropriate expertise when carrying out investigations, which is repeated in the context of disciplinary panels.

Taken together these are changes that make sense, and pick up a range of issues that will have come in before the consultation was pandemically paused a year ago. As noted above, we looked in detail at the proposals overall when they emerged last year. What’s interesting here is the status of the “statement” now, and where there’s still work to do.

Expectations or suggestions?

The thing about OfS’ regulatory framework is that it was never really designed to address issues like harassment and sexual misconduct, or indeed stuff like mental health. Whether that was by design, or an oversight, we may never know – but students, your Radio 4 today listener on the Clapham omnibus, the press and media and apparently ministers all assume that the universities regulator does look at the big issues surrounding universities’ duty of care to students – and so OfS has to play along.

In the past it’s done this in a couple of ways. The most obvious has been to disburse what HEFCE used to call “Catalyst” funding to universities working on these sorts of issues, and then reviewing the learning from those projects for wider implementation. It’s not a terrible approach when you’re trying to solve a wicked problem.

But in the absence of decent national prevalence data it’s hard to demonstrate that it’s an approach that has been working. And into that vacuum endless press stories covering single incidents or pieces of polling show up the fault in those kinds of “inspire and disseminate best practice” approaches – that there doesn’t appear to be a standard people can rely on, and everything feels like it’s getting worse.

There’s a lesson here about spotting the issues that are so serious that they are unsuited to that kind of regulatory intervention.

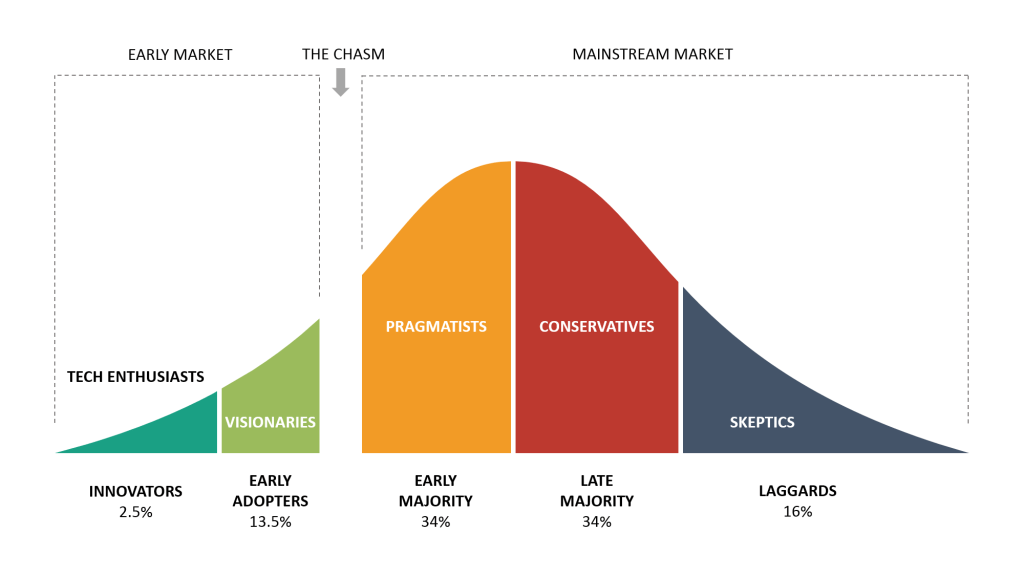

But there’s also what I might call the adoption question. Any student studying the adoption of technology will be familiar with the curve that suggests that innovators and early adopters are only followed by pragmatists and conservatives when some kind of intervention bridges the chasm. We can argue here about whether that’s funding, or national voluntary guidance, or “crackdowns” or a speech from the SU President at governors or some other things that spurs the action required – but let’s assume that in the model, the pragmatists do what they think they’ll be told to do, and the conservatives only do it when they’ve been told to. And once you’re at the laggards – you need real force or threats.

And that’s a problem if there are no threats or force. A year ago OfS’ statement of seven principles was so “square peg in round regulatory framework hole” that only three of them were grounded in actual regulatory conditions. In this version – partly because there’s not been the time to consult formally on a change to the regulatory framework – none of them are.

In other words, it’s a regulatory step backwards from that which students were promised a year ago, with some intensified rhetoric from the CEO and the minister to cover it. Whether that causes the conservatives, the skeptics, and those on the register that are just too small to take this as seriously as they should (given the risks are bigger the smaller the community) remains to be seen – and it means we’re still not at the point where students might regard what’s written as their right.

It is, in other words, at best a statement of strong suggestions, not of actual expectations.

What’s missing

The other important question to ask is what’s (still) missing. A year on from the pausing of the consultation means a year has passed without everyone being able to feed back on what they think needs to be done, explained or covered that is proving really difficult. Some that spring to mind are as follows:

- The statement (and the consultation that surrounded it) said plenty about student-student misconduct, but hardly anything about staff-student misconduct. This is complex stuff, the 1752 group has had plenty to say in this area, and in many ways it’s quite extraordinary that there’s still a debate at all about whether staff inside universities should be able to even attempt to have sexual contact with students given research like this.

- The OfS approach outlined last January deliberately avoided recommencing the collation of statistics at provider level in this area, and this version still does – which is odd for an otherwise metrics-obsessed regulator. If OfS can find ways to compare universities based on degree classifications, surely it can compare universities on their handling of issues like this.

- Related to that is the issue of prevalence. Mentioning it is one thing – but surely it’s not beyond us as a sector to be nationally surveying students on the prevalence of harassment and sexual violence, not least so we can determine whether the issues are experienced differently by different types of student or in different types of institution? OfS runs a national student survey and both could and should step in here – as the Irish Higher Education Authority is.

- The ongoing issue of jurisdiction needs a fix when it comes to partners. The OfS approach just says that even if a student is harassed or assaulted on a year abroad, in a franchise provider or on placement, it expects the university to take responsibility – but think about that for 5 seconds or more and you see a sea of deep complexity that the sector needs help with.

- There’s another jurisdiction issue too, when it comes to harassment or assault that involves two students at a university but where the actual university context is weak (they may not have known each other were at the university, or may have known each other previously – or are workmates at a separate employer). A national complex case review should pick up these issues for further investigation and resolution.

- The OfS statement and surrounding material was fairly weak on online misconduct which was an obvious oversight a year ago, let alone now that we’re moved much of the sector into the cloud. Universities UK has done great work here that should be incorporated fully into the OfS standard.

- Prospective students and their parents need to know about the policies a university has in place in this area and the plan a university has to tackle the issues. I’m convinced – as are people like Graham Towl – that this would be useful information to know. Is it really beyond OfS to include information like this on DiscoverUni?

- It remains the case that student-student misconduct where the students involved attend two different universities is not handled well – for all the “single reporting portals” it’s really hard to raise an issue about a student in another university. This is a real problem in almost every university in the country, and plenty of towns adorned by two providers. Someone surely needs to bottom out the data sharing issues and recommend a law change if they can’t be. Ditto cases that have involved students at a school that never got handed to the police.

- It’s not a stretch to imagine that the way we both prevent misconduct and process allegations of it needs to be sensitive to cultural difference, given how diverse and international the student body is. There are mild nudges toward taking this seriously in the new version, but broadly there’s a real danger that approaches centred on “traditional student“ conceptions of class, ethnicity and British norms are hiding pockets of abuse that need to be found.

- On disciplinary panels, the OfS statement says that they should be free from any reasonable perception of bias, be diverse and include student representatives where appropriate. It also says all panel members should be appropriately trained in handling complaints of this nature and be independent from the investigatory process and specific case being considered. The new version now nudges toward expertise in investigations themselves. But we should more explicitly ask ourselves the standards we might expect from investigations, whether/how small providers can do this at all, and what the circumstances are where a university should bring in an external to carry out such a process to improve quality and confidence from students.

- We need the issue of risk analysis to be taken much more seriously than it is now. Not all parts of a university are the same – and every university will have pockets of provision where abuse may be more likely to thrive and much harder to challenge. Think elite sports clubs, medical schools, research fieldwork, schools liked to a profession, PGR students in small departments and so on. An approach that requires universities to risk assess and apply extra steps to these pockets is desperately required.

- Finally, the gaps and overlaps when you remember that students’ unions usually have conduct codes and employment procedures, as well as universities having both for their students, as well as confusions over PGR students, all again suggest that a complex case review handled at national level is needed to beef up the standards and guidance to universities in this area.

What I’m really getting at is that after a complex or difficult case – and so many of these that have arisen have proved to be complex or difficult – you need real courage and actual coverage to be able to address the lessons publicly, not least to avoid the liability issues when the sunlight gets in. Only rarely does that happen – and nobody starts out wanting a review of the sort we saw at Warwick.

In other words – we need a national serious cases review now, convened by OfS, so we don’t waste another year working out if a set of standards designed in a petri dish will work out for students in the real world, and by avoiding the hardest edges of this stuff as it has played out in real cases. And ministers need to fund the same sort of “what works” approach we see in APP work, but instead in duty of care and harassment/misconduct prevention work.

So as I said a year ago when we saw the draft – this is good (if overdue) news, it probably would never have happened under HEFCE, and students will be better protected as a result.

But what the story reminds us of is that as constituted, OfS is not fit for purpose on these “duty of care issues”. Mental health is the other glaringly obvious omission. And instead of talking tough, ministers should give the regulator the powers it needs to tackle them, the funding it needs to unpick them, and the backing to understand and learn from their increasing complexity – rather than the childish superficiality of another minister riding to the rescue with a “crackdown” or a “clampdown”.