The awarding gap has become a significant focus in UK higher education as a quantitative measure of inequity in student outcomes.

This issue demands urgent action if we are to create socially just provision. However, current methods for measuring these gaps have critical flaws and may even undermine our efforts to achieve fairer outcomes.

The standard UK awarding gap metric compares the percentage of students from two groups who obtain a first-class or upper second-class degree (First/2:1). For example, if 80 per cent of non-disabled students achieve a First/2:1 while only 70 per cent of disabled students do so, this would reflect a 10 per cent awarding gap.

This metric has become widespread in UK HE policy, including via Office for Students key performance measures and Access and Participation Plans. The awarding gap, particularly the ethnicity gap, has been the subject of national reports, and many institutions are working toward eliminating these disparities.

However, despite this focus, the way we currently measure awarding gaps is fundamentally flawed. If we are genuinely committed to creating equitable educational outcomes, we need better metrics that more accurately reflect the experiences of students.

Issues with the current metric

Imagine two students, Theo and Ayesha, both enrolled on the same course at the same university. Theo went to a private school, and his university-educated parents pay for accommodation near campus. He is confident that he will secure a good job after graduation due to family contacts, so spends more time on sports than on studying. Ayesha is the first in her family to attend university. She lives at home with multiple younger siblings and commutes an hour each way to campus. She works a substantial number of hours each week, and she is expected to care for siblings alongside studying.

Theo and Ayesha both achieve a 2:1 degree. From the perspective of the awarding gap metric, this is an equitable outcome. But clearly, this is not the case as Ayesha had to overcome significant challenges to earn her degree. So in this case an awarding gap of zero fails to recognize the true inequity in student experience and outcomes.

Arbitrary thresholds

The awarding gap metric relies on an arbitrary threshold for defining success. The metric only compares the proportion of students receiving a First/2:1, ignoring all other levels of achievement. If every Theo achieves a First while every Ayesha earns a 2:1, there would be no measurable awarding gap. Yet students like Ayesha are consistently disadvantaged. The current metric also does not account for students who do not complete their degrees. By focusing only on those who graduate, we risk overlooking inequitable degree completion rates.

The use of a 2:1 as the awarding gap threshold is an arbitrary choice. This is typically justified on the basis of a 2:1 being a requirement for postgraduate study or entry to graduate careers. However, the majority of graduate employers no longer require a 2:1, and many masters programs now accept students with a 2:2. The OfS has recently updated its key performance measure for Black students, focusing specifically on the gap in first-class degrees. However, most institutions and the Access and Participation dashboard continue to use the First/2:1 gap. Some institutions have started to look at both metrics, but shifting the focus to first-class degrees may have unforeseen consequences.

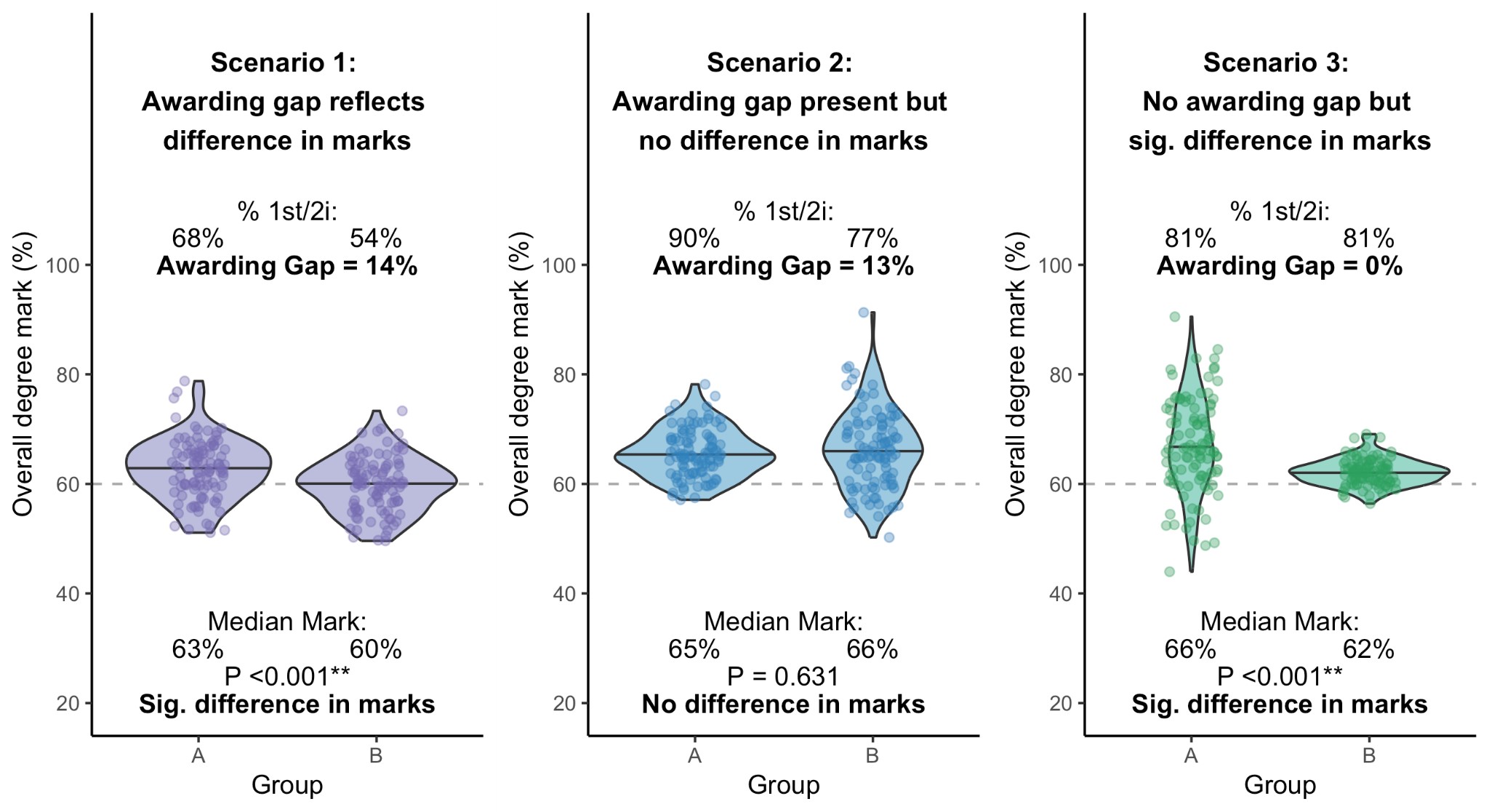

The threshold based construction of the metric also gives a non-obvious relationship between the marks students receive and the subsequent awarding gap. As mark data is not publicly available, I have simulated student outcomes for a fictional university to highlight some of the issues (Figure 1). Most in the sector are operating on the assumption of Scenario 1, whereby the awarding gap reflects a significant difference in student marks. However, my simulated Scenario 2 illustrates it is possible to have a large awarding gap with no difference in underlying marks. Conversely, in Scenario 3 there is no awarding gap but a significant difference in marks (Figure 1).

Three hypothetical scenarios to demonstrate the limitations of the awarding gap. Each datapoint represents one student, filled shapes the underlying data distribution. P values give results of Mann-Whitney test for differences between group A and B.

For institutions or departments with data resembling Scenario 3, the metric fails to identify substantial inequity, so no interventions would be made. If the metric isn’t technically able to robustly identify inequity, should it guide institutional and sector policy?

Institutional and departmental gaps

When an institution reports an awarding gap (for example, a 15 per cent gap) it doesn’t necessarily mean that this gap exists equally across all disciplines. In the “within-area” gap model, each department experiences a similar gap, although the exact percentage may vary. In contrast, the “between-area” gap model suggests that one department may have significantly lower outcomes for all students and disproportionately high enrolment of students from disadvantaged demographics. This could create an institution-wide awarding gap even if students from the demographic focus group outperform peers in most other areas.

If the gap is driven by one or two departments, the focus should be on improving outcomes in those departments rather than addressing an institution-wide issue that may not exist. The current awarding gap metric, however, does not distinguish between these scenarios, which can lead to inappropriate interventions.

A way forward

So, what should we do? Metrics are only useful if they help identify appropriate interventions—and they can be harmful if they obscure the real causes of inequity. More statistically robust metrics are needed, e.g. those that reflect unequal mark distributions through z-scores. A composite measure that captures a range of student outcomes would offer a more comprehensive view of equity and inequity.

We need to move beyond the crude, institution-level metrics that are currently in use. Given variation in outcomes between subject areas, a discipline-level metric that allows for appropriate benchmarking would be far more useful.

The inequity represented by the awarding gap is real and must be addressed urgently. However, we have an ethical responsibility as a sector to ensure that the metrics we use are technically valid and theoretically sound. Right now, the UK awarding gap metric fails on both fronts. We need to come together as a sector to develop better measures—ones that can genuinely inform policy and practice and help us eliminate educational inequities for all students.

Further reading: Hubbard, Katharine. 2024. “Institution Level Awarding Gap Metrics for Identifying Educational Inequity: Useful Tools or Reductive Distractions?” Higher Education.

Awarding gaps should not be separated from Admission gaps.

Precious is an average performing black female. She goes to university and achieves a 2:2. Connor is an average performing white male. He does not go to university. If the Admission gap is not taken into account, then Precious counts towards the Awarding gap whereas Connor does not. Is this equitable?

Let me elaborate. Suppose there are ten black and ten white people who pairwise have identical capacities. Six black people go to university and 4 white people go to university. Two of the black people and two of the white people achieve at least a 2:1 (consistent with them having pairwise identical capacities). Considering only the Awarding gap, this seems inequitable: 33% of black students (2 out of 6) achieve at least a 2:1 whereas 50% of white students (2 out of 4) achieve at least a 2:1. However, when the Admission gap is taken into account, it is the… Read more »

Its a percentage point gap. A 10% and 10ppt gap is very different. Its important we consider the implications of the gaps, but also that we report the gaps consistently.

I think there’s some very dodgy thinking in this article! If in the example we accept that if her circumstances had been different Ayesha had the potential to do even better and get a first I accept that you can argue she has been disadvantaged by context and circumstance. However, if the assessment processes on the course in question have been valid and rigorous (I concede that this is a big if!), and therefore fair, then the fact that the two students get the same grade is right and fair as that is the standard they both reached.