I generally tend to view myself as someone with opinions, and I expect that I am regarded as someone who is confident in those opinions.

It’s partly a show of course. I learned early on that the pretence of confidence – albeit latterly tempered with the capacity to see others’ views and change one’s mind – was key to getting respect and having confidence reflected back in the middle class world I was starting to inhabit.

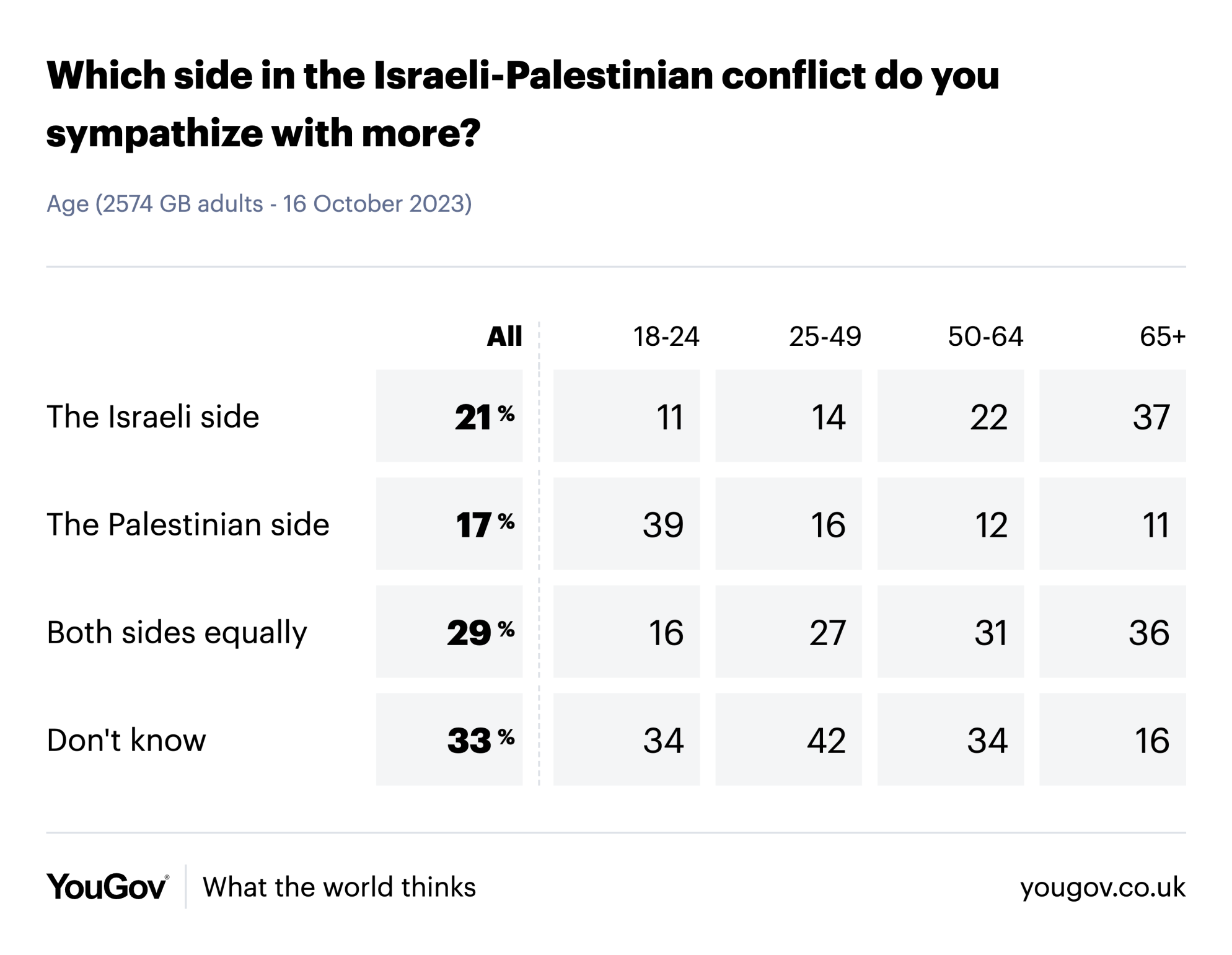

So when, last week, YouGov published its polling on where the public was on the Israel/Gaza conflict, I was briefly caused to reflect on how I would have answered the question on where my “sympathies” lay between Israel and Palestine.

And I feel some shame in admitting that I was, and still am, in the “both sides” camp.

That the stats indicate that the younger you are, the more likely it is that you’ll have taken a side should not surprise us.

Nor should the relative size of the pro-Palestine group. Being suspicious of the state may, in this context, represent a kind of conspiracy theorism bordering on antisemitism that we should take seriously. But it’s also a characteristic that is related to both being young, and the diversity of young people.

Both sides?

This isn’t, though, about me slowly morphing into a centrist dad. I’ve been in that “both sides” group for as long as I can remember.

I’ve told myself all sorts of stories and developed all sorts of excuses for that over the years.

It’s complicated. I don’t understand it. I haven’t the time to get into it. And so on.

But when you’ve spent a career working with some of the most politically engaged young people in the country, you also know the sense of disgust that is communicated back when you’ve not picked a side.

And when you’ve been to as many talks, and read as many leaflets, and prepped for as many meetings as I have, you also know you’re telling yourself a lie.

Whatever the episode, or particular manifestation of conflict in the middle east, there’s always a big bit of me that thinks they’re probably right – that I haven’t considered X or Y, or that once you take no side, you by default take the other side.

It’s also pretty hard to set aside the increasingly visceral evidence of the impact on humans that we have now have (social) media access to on both sides of the conflict.

I’ve had other excuses. I work in education, where it’s crucial to think about and empathise with others’ views, opinions and plights.

And my other excuse is that pre-Wonkhe, and for half the week now, I’ve pretty much always worked in the administration of, management of or support for student organisations.

It’s not appropriate, or wise, I’ll have told myself – and them – for me to have a view, or engage in activism on one side of that view.

Not least when, for as long as I can remember, the student movement has never been more than six weeks away from another episode of the conflict manifesting in the democratic politics of the organisations I’ve been around.

Who has power?

But there’s always been a truth about that studied neutrality. Not only has it always been treated with disappointment, it’s always been treated with suspicion. Because from time to time, either through influence or ownership of some process or other, it’s involved the exercise of a kind of power, that I learned many years ago to try to exercise with extreme care.

And the reality is that power is neither equally distributed nor equally exercised across our society.

The middle east conflict may not be unique, but I think one of its defining characteristics is the way in which it causes supporters on each “side” to claim – with real evidence – oppression and discrimination.

That matters, I think, because the debate over free speech in recent years has so obviously been about a particular kind of free speech.

Regardless of the legal technicalities, for half a decade, a maximalist framing of freedom of speech, and a minimalist framing of oppression has dominated the discourse.

And for many students, their university or their SU has not represented some bulwark against simplistic state control. It has looked like it’s playing along.

But while it was obvious then that an apparently neutral and apolitical free speech law was being passed to partisan ends, it’s just as obvious now that apparently neutral laws and apparatus aimed at protecting people from discrimination and harm is being used to partisan ends.

As such, pointing out the “sandbags on the see saw” is one thing to do – and I’ve done it many times here. Following the sort of sensible steps outlined in Advance HE’s interim update to its Promoting good relations in higher education guidance will also help – although like many documents of its ilk, while it’s helpful on process and vivid on striking balances and describing what can feel like competing demands, it perhaps inevitably is less helpful on the making the actual calls themselves.

Exercising extreme care

But I think something else is important too. Higher education is at a real danger point that its leaders should consider carefully.

Nobody believes that universities are truly autonomous of the state, or that they are immune from political or economic pressures.

But students also expect a degree of resistance, reflection, critique and push back on any expectation loaded onto it.

When I think of my job, I am enormously lucky to be able to have opinions that, apparently, run counter to many of those that might lead or manage or even work in universities.

Students and staff should regard that “academic” freedom as important too. But everyone knows that the freedom is not unfettered.

The bills have to be paid. The outcomes have to be secured. The confidence has to be won. The reputation has to be managed.

And so when I think about how the state behaves in a conflict like this, I am caused to reflect on earlier parts of my career.

I know how this works. The local paper expresses outrage. The DfE Prevent coordinator has a quiet word. The local police drop an email in about a poster or facebook post they’ve seen. A lay governor books half an hour into the diary. A minister asks to be put through to the VC.

There is, and always has been, a political economy to the way the rules are used, funded, deployed and enforced.

I should be clear – not everyone that ticked Israel in the YouGov poll support the government of or actions of the Israeli government, and neither do all Muslim, Palestinian or even pro-Palestinian people support Hamas.

But I can understand why Jewish students or those with sympathies to Israel’s cause would feel a deep and instinctive pain of not experiencing the automatic outpouring of support that Ukraine felt when Russia invaded – especially when activities or slogans tip into antisemitism.

And for some of those that ticked “Palestine”, I can understand the injustice at having had “but it’s free speech” played back every time racism or oppression has been experienced in recent years – only to have talks or protests questioned or shut down by those concerned to avoid discrimination or extremism now.

As such as well as decisions, these sorts of evaluations need discussion, and at least an attempt at perspective-taking – however difficult.

Whose job?

I listened carefully to immigration minister Robert Jenrick the other day on Radio 4, doing what ministers have done in this space for decades – incoherently boasting that he would deport international students despite not breaking the law, when his government has been demanding that universities champion free speech within the law for half a decade.

And as he refused to discuss whether the government would proscribe Hizb ut-Tahir, I am reminded of “common sense” MP John Hayes, telling me when I worked at NUS that he was thrilled we were no-platforming them – because the government wouldn’t.

The point isn’t that higher education should always, or never, do the state’s dirty work. Autonomy does bring responsibilities in the balance – to champion free speech, cherish critique, prevent harm and work to combat discrimination and prejudice all at once.

But too often this week I’ve watched as some – not all, but some – universities have hid behind their students’ union, or in some cases offered no support at all to their students’ union, in making astonishingly complex decisions about whether to allow or ban something their students want to do.

In the grand scheme of war this compliment is meaningless – but I do think it takes real courage for both student leaders and SU staff to front out those evaluations, decisions and judgements.

To explain why, to be open to challenge, to explore the complexity, to be demonstrably honest about the weigh up and to – especially when not instinctively in the “both sides side” camp – to cause groups of students to understand why a decision is being made is not easy.

This work, this hard work, might feel like it’s “better coming from the SU”. But maybe that’s hopium and copium. And in any event, they need back up.

Having their back

First, university media teams need to be directed to end that practice of saying “we’re not responsible for the SU, it’s autonomous” – as if anyone in the media or the public understands or accepts that.

Next, the legal firepower that the university has should be deployed to help those making judgements do so. That need not be as it often is now – a direction or off-the-record command. It should be a collaboration, where those making the calls have access to the advice that universities have.

Universities, as Royal Holloway’s Andrew Boggs does on this week’s Wonkhe Show, should find ways to celebrate some of the events, talks and discussions that are happening on campus as examples of responsible free speech and students engaging with the world around them.

On free speech regulation, the entire sector in England should consider adopting a joint free speech code with their SU. If these things are rules-based, there’s not a cigarette paper between the judgements that should be being made to allow, promote, discourage or ban.

And to those leading universities – this kind of thing is why you’re paid the big bucks. Outside of the “one community” emails, the students tangled up closely in this conflict – those that have “taken a side” – are not hearing enough from you, directly.

In a context where both the young and the public trust institutions even less than they ever used to, it’s never been more important to roll the sleeves up, engage on the complexity and get involved. It won’t win friends – but it may well secure respect.

This represents very well my views and experience as well. My natural sympathies are with the oppressed and the dispossessed (I couldn’t do otherwise: part of my family was cleared off their land in the Highlands in the late nineteenth century; others lived at the whim of the mine owners), but I also am nauseated by random extreme violence against civilians. I also dislike radical, often very macho, posturing, which is often what we see in these contexts in universities. I often ask myself what I would do if I, as a Scottish democrat with great sympathy for the Irish… Read more »

This is the 5th article/blog written about this on here and it’s starting to become a bit uncomfortable. Most of us saw the absolutely awful deleted post in response to this. Whilst the freedom of speech bill is an abomination, academia has some real real issues around the current world events (including at the organisation the writer has repeatedly defended over this on here). I think wonkhe has made its point on this and should stop stirring the pot…