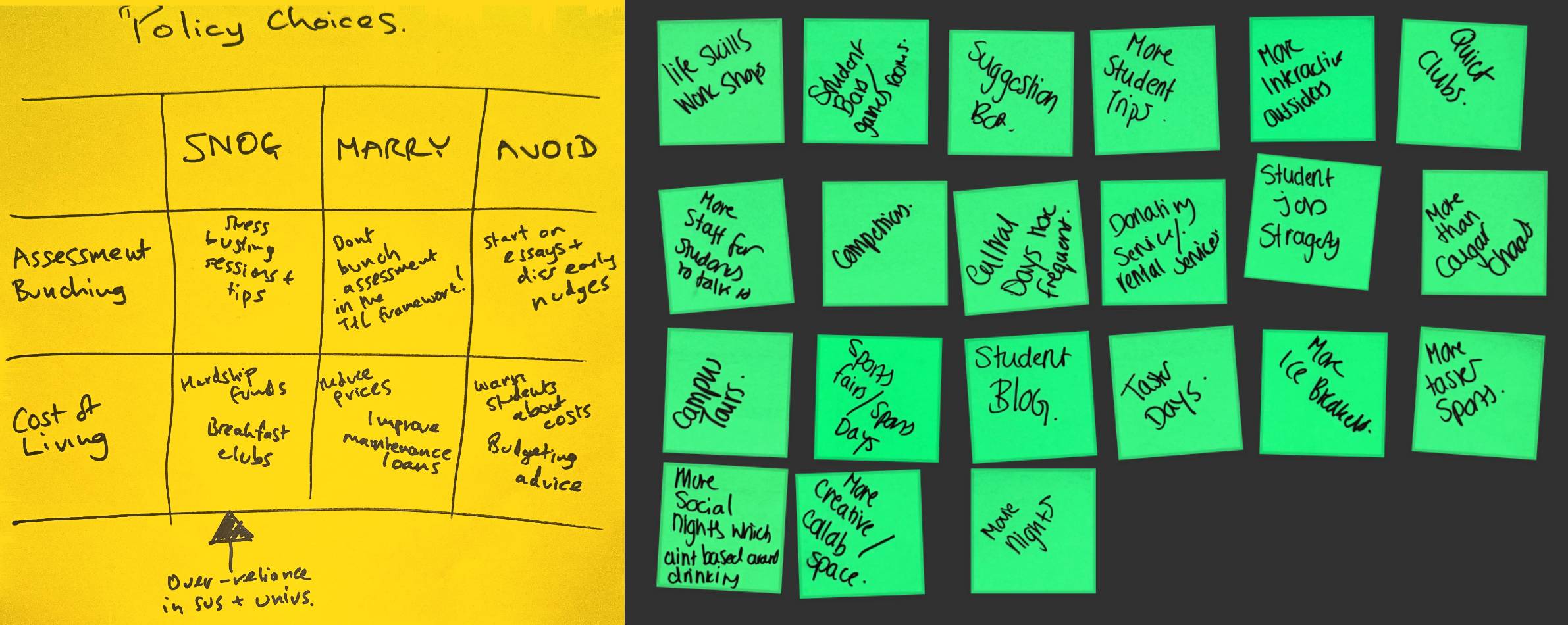

One of my go-to exercises when I’m out and about delivering training for new SU officers is called “Snog/Marry/Avoid”.

It’s a simplistic heuristic. When students face problems, you can either snog them – help students cope with some sort of intervention; marry them – remove the problem altogether; or avoid them – which is about warning students so that they don’t experience the issue in the first place.

So if students’ deadlines are all bunched up, the SU could “snog” with assessment period coping classes or chillout rooms, “marry” them by lobbying to get assessments spread out, or “avoid” by somehow causing students to not leave writing their dissertation until the last minute (or even choosing modules, universities or courses where that sort of bunching isn’t present).

The cost of living crisis has some similar options. Snogging cozzy livvs is about hardship funds and free breakfasts, marrying is about getting costs for students down (or at least loaning them enough to live on), and avoiding is about being upfront about costs in that city so that students can either choose a different one, or at least save up sufficiently.

As such, one of the problems I’m picking up is that everyone’s lips are a bit sore. Many of the initial crisis-era “snog” initiatives seem to be being cut, hardship funds and bursaries are being rationalised and spread even thinner, and temporarily frozen costs like rent, printing, gym memberships, laundrettes and lattes are all climbing back up again in price.

So on the assumption that the marriage of majorly improved maintenance support for home students and currency miracles for international students are not coming any time soon, that pretty much only leaves “avoid”.

Helping students to budget with information on likely costs that they’ll face is both an important life skill and a crucial piece of the information, advice and guidance puzzle. It allows them to fulfil their aspirations, realise their ambitions, and… eat.

Over the past two summers I’ve spent train delays looking at what universities say about costs – and both years as well as pockets of honesty and accuracy, I’ve also come across a cavalcade of misleading and out-of-date information. I also looked at London earlier in the year and found similarly poor information.

So when I started googling again this month, my hope was by now, a few years into a prolonged crisis, the sector would have its act together. And while some of the howlers I’ve highlighted in recent years have been fixed, the picture is still pretty poor.

Careful now

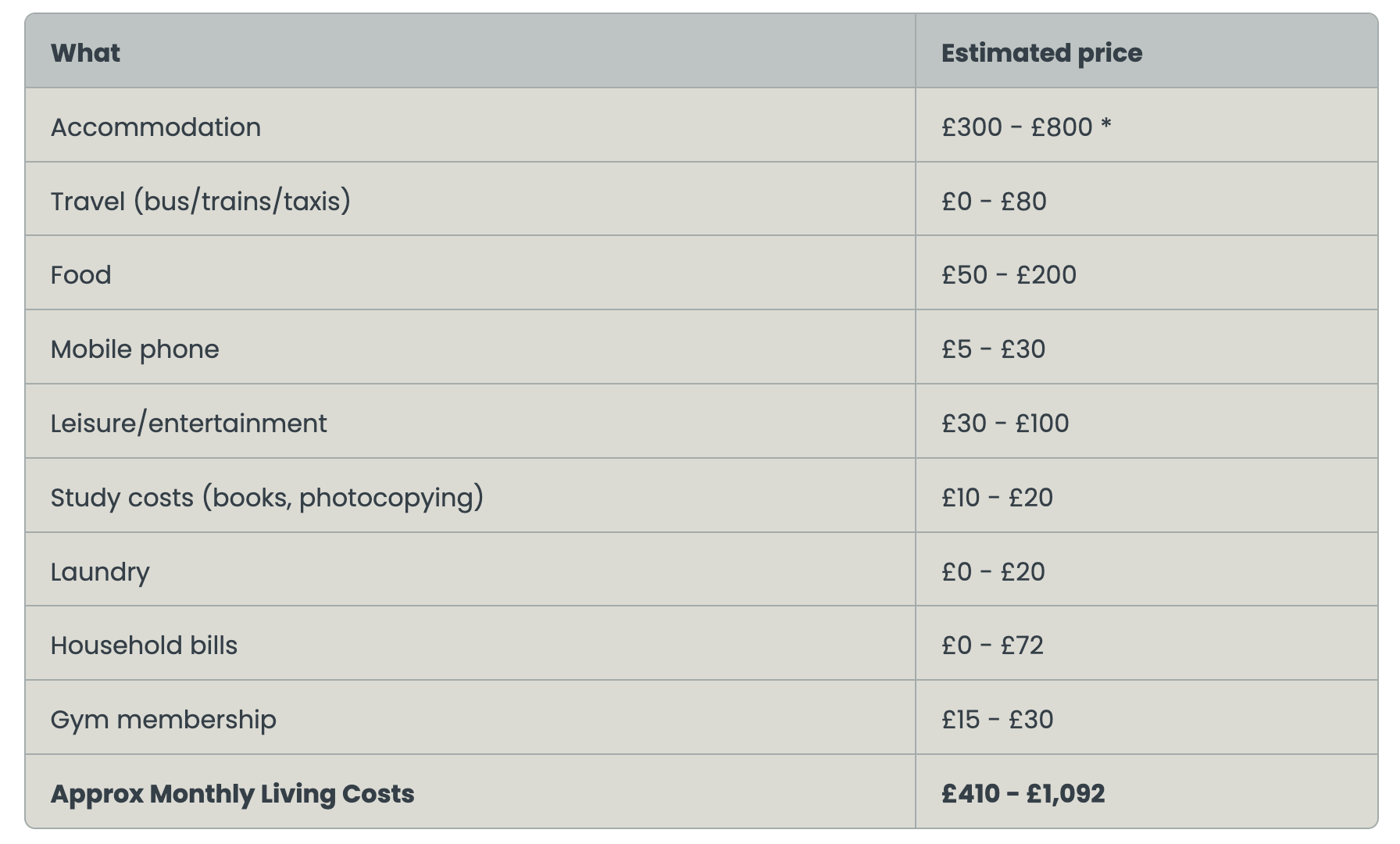

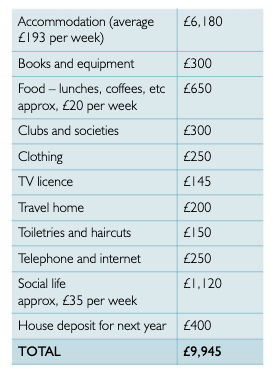

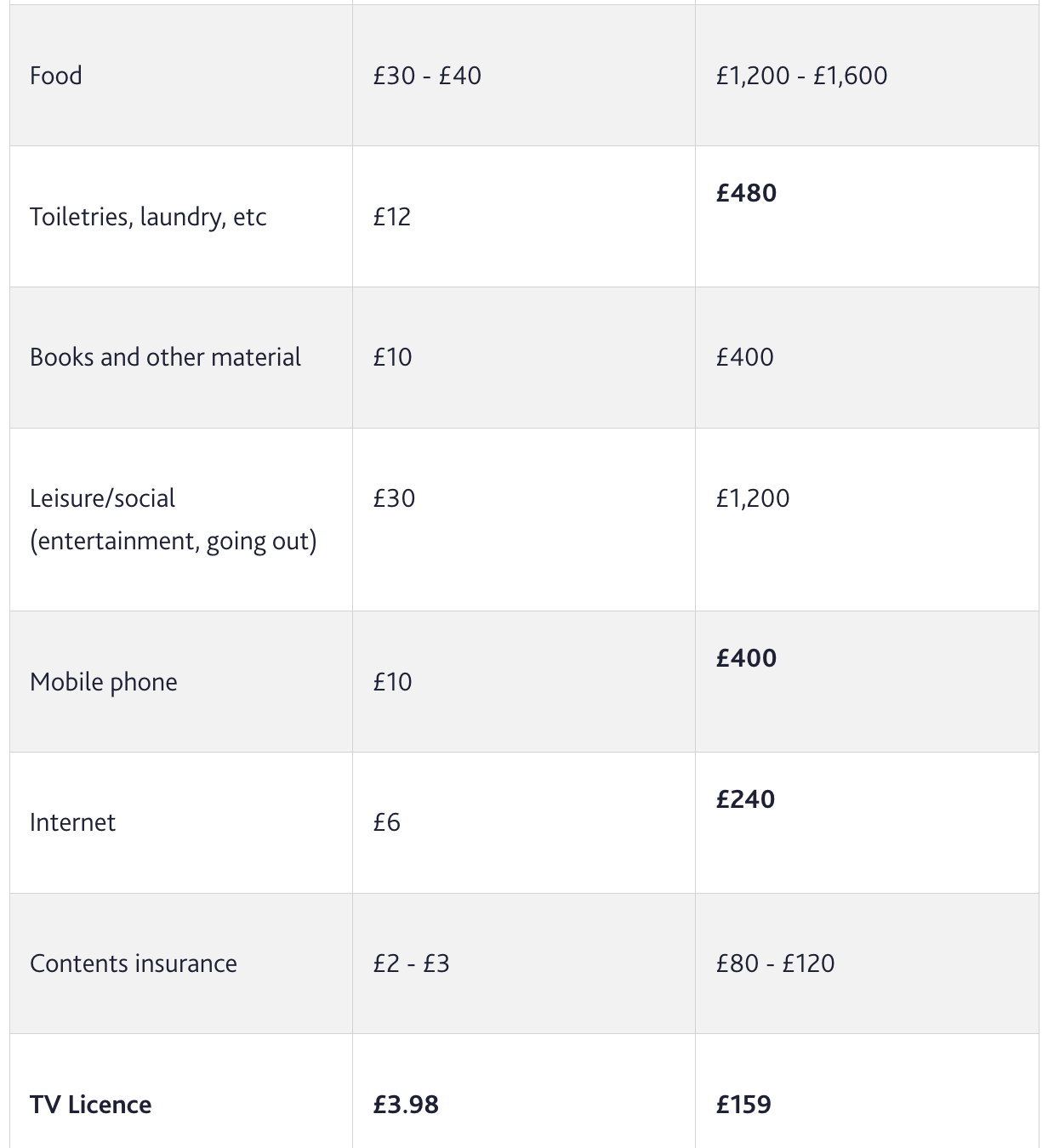

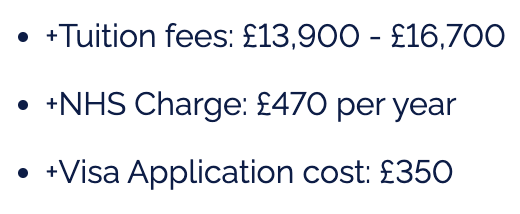

We begin at a university in the North West, where students are told that it is important to “budget their money carefully”, with this handy table of “examples that demonstrate current living costs per month”:

The problem is that the table is exactly the same as it was back in 2020, despite where inflation has been since:

Amusingly, that little asterix used to refer to some detail about university-run housing prices in 2017. That was wildly out of date in 2020 – now the asterix just hangs forlorn, because someone has remembered to delete the accompanying text but not actually update any of the figures.

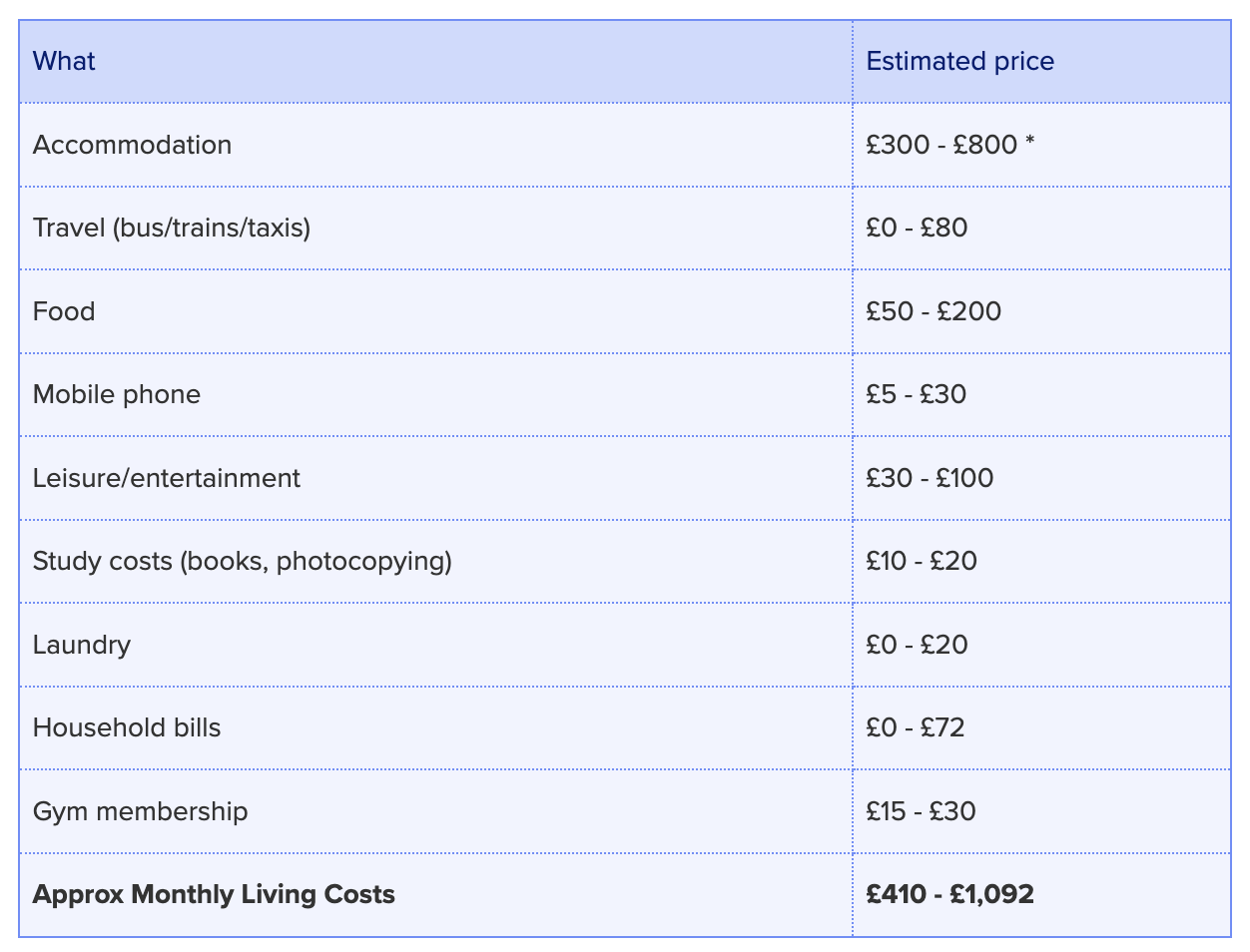

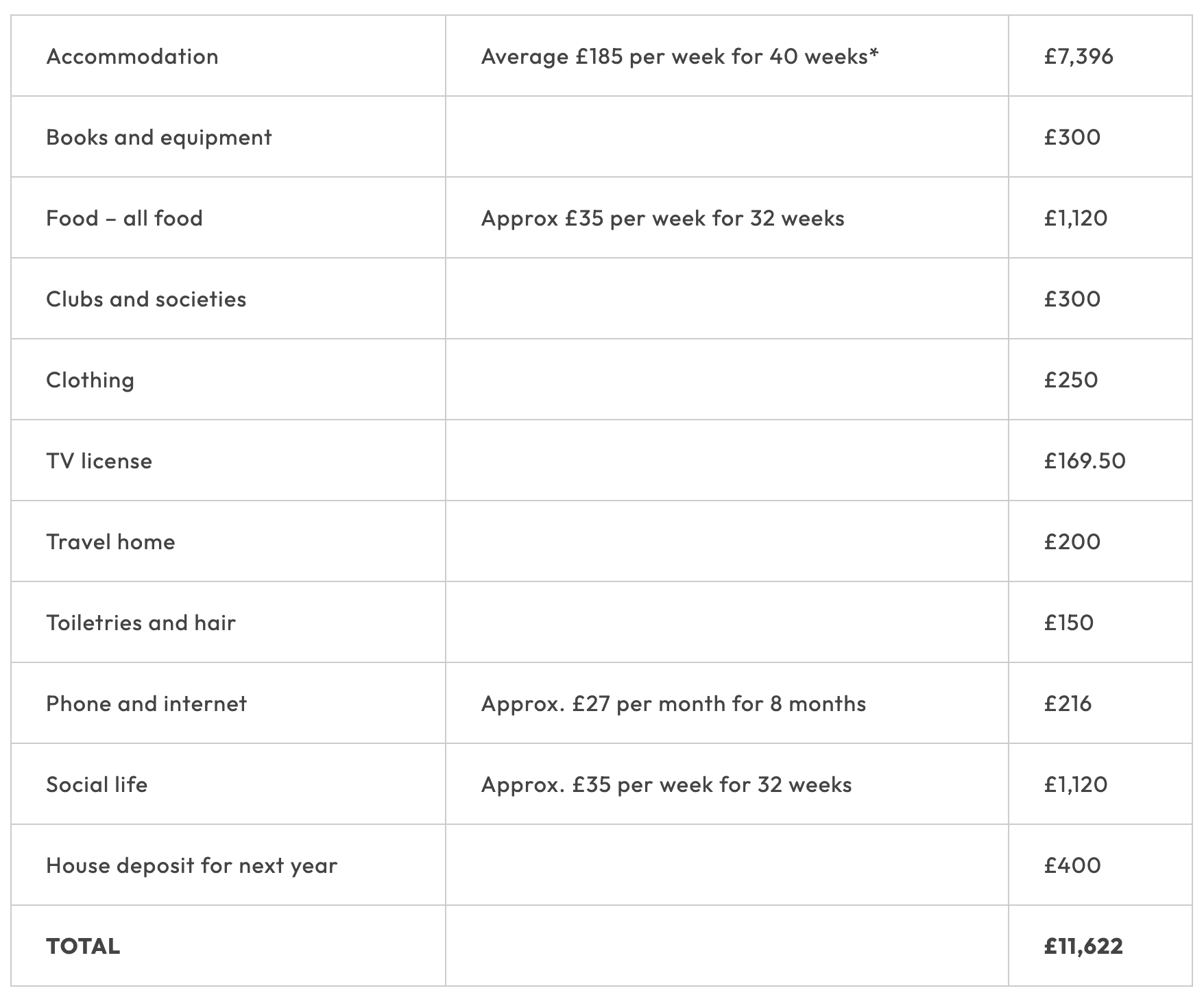

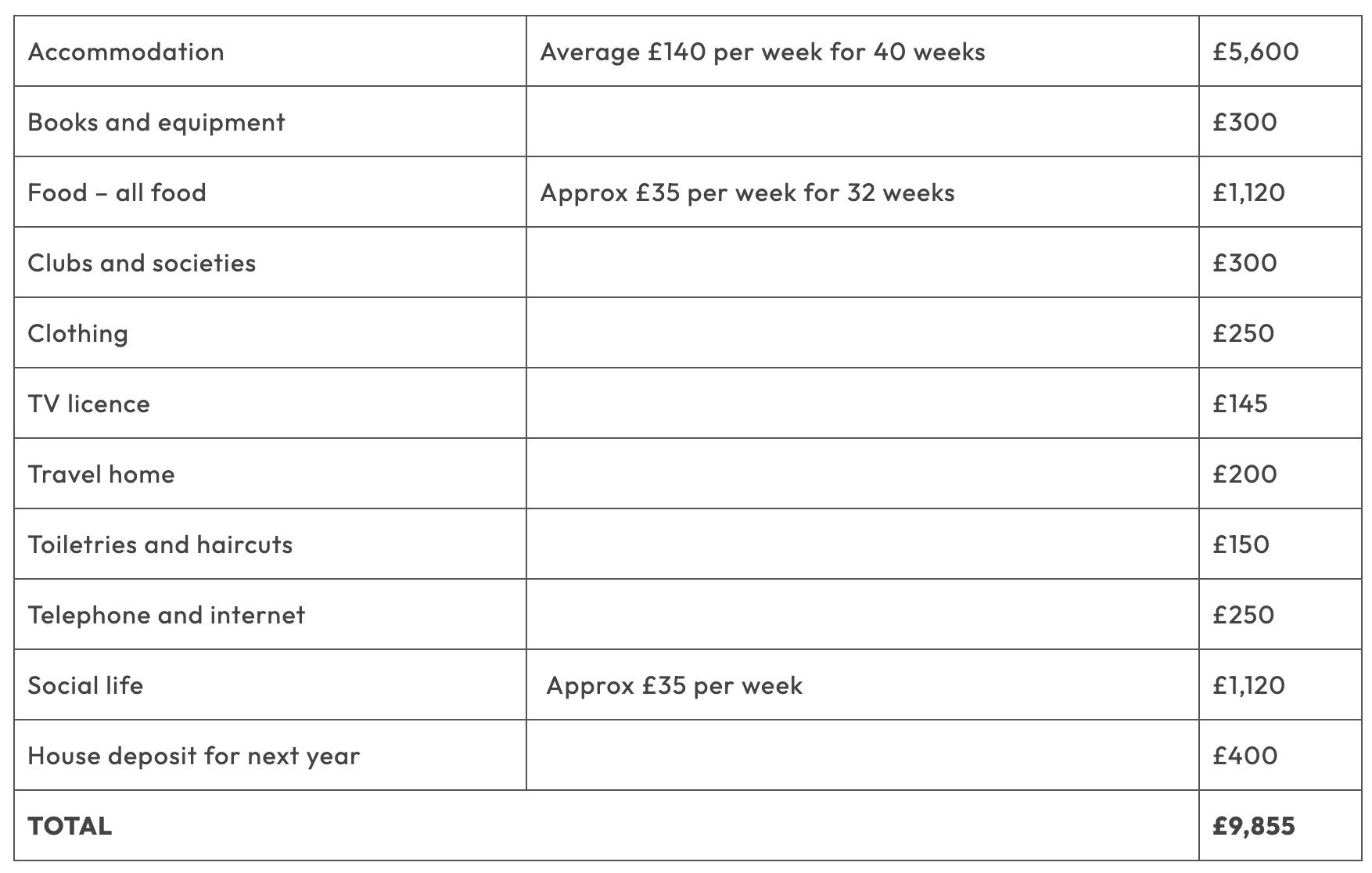

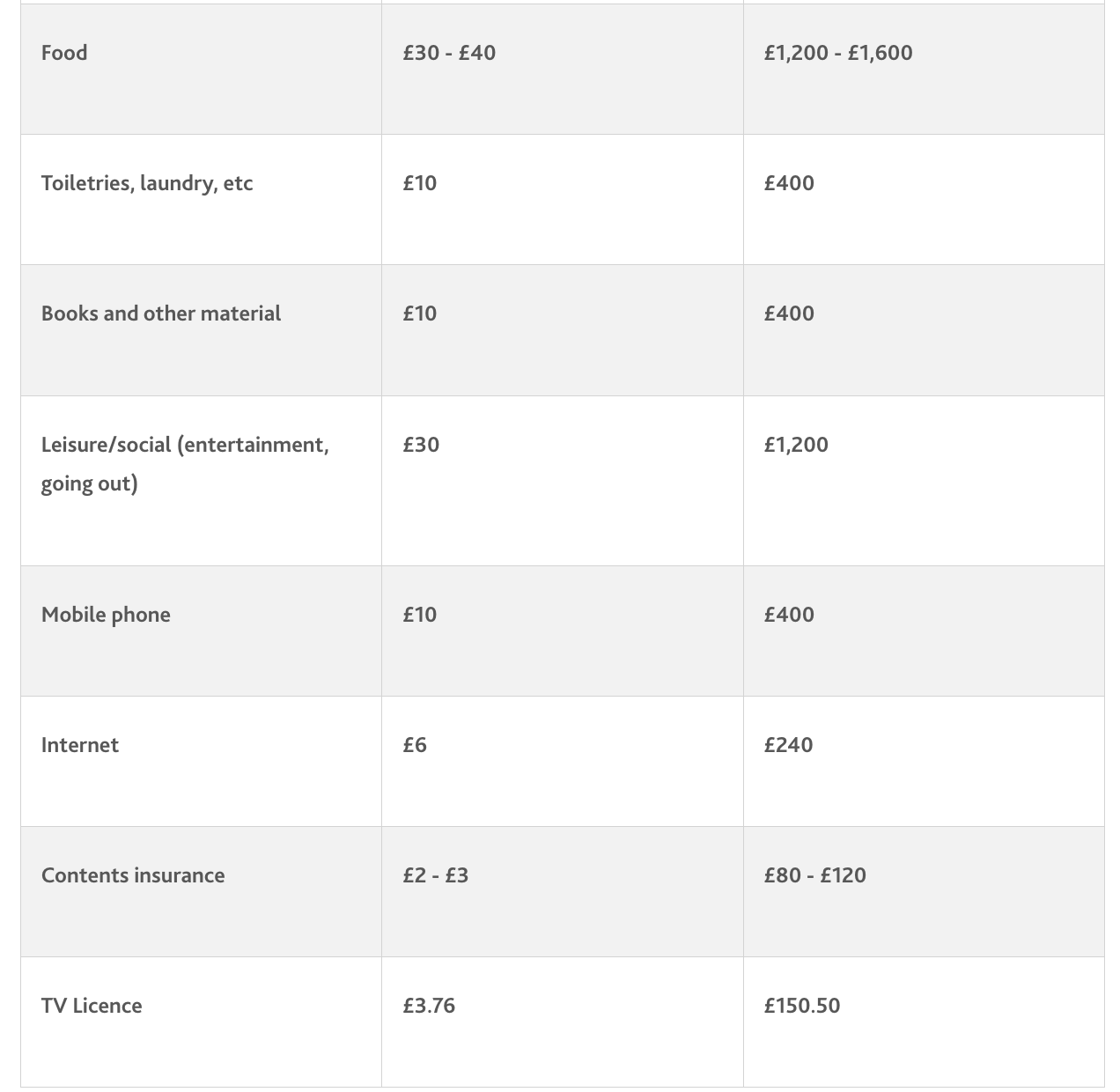

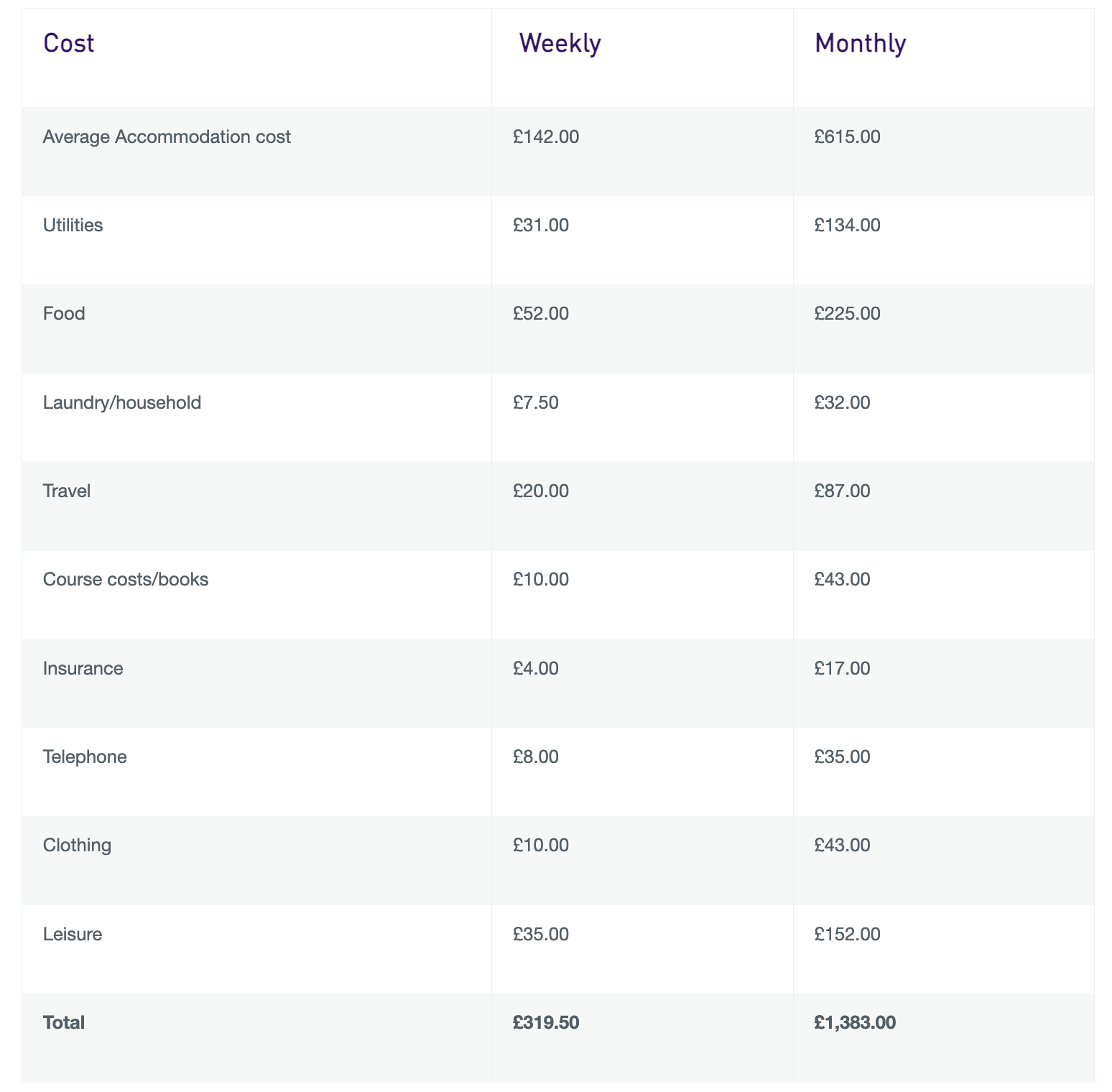

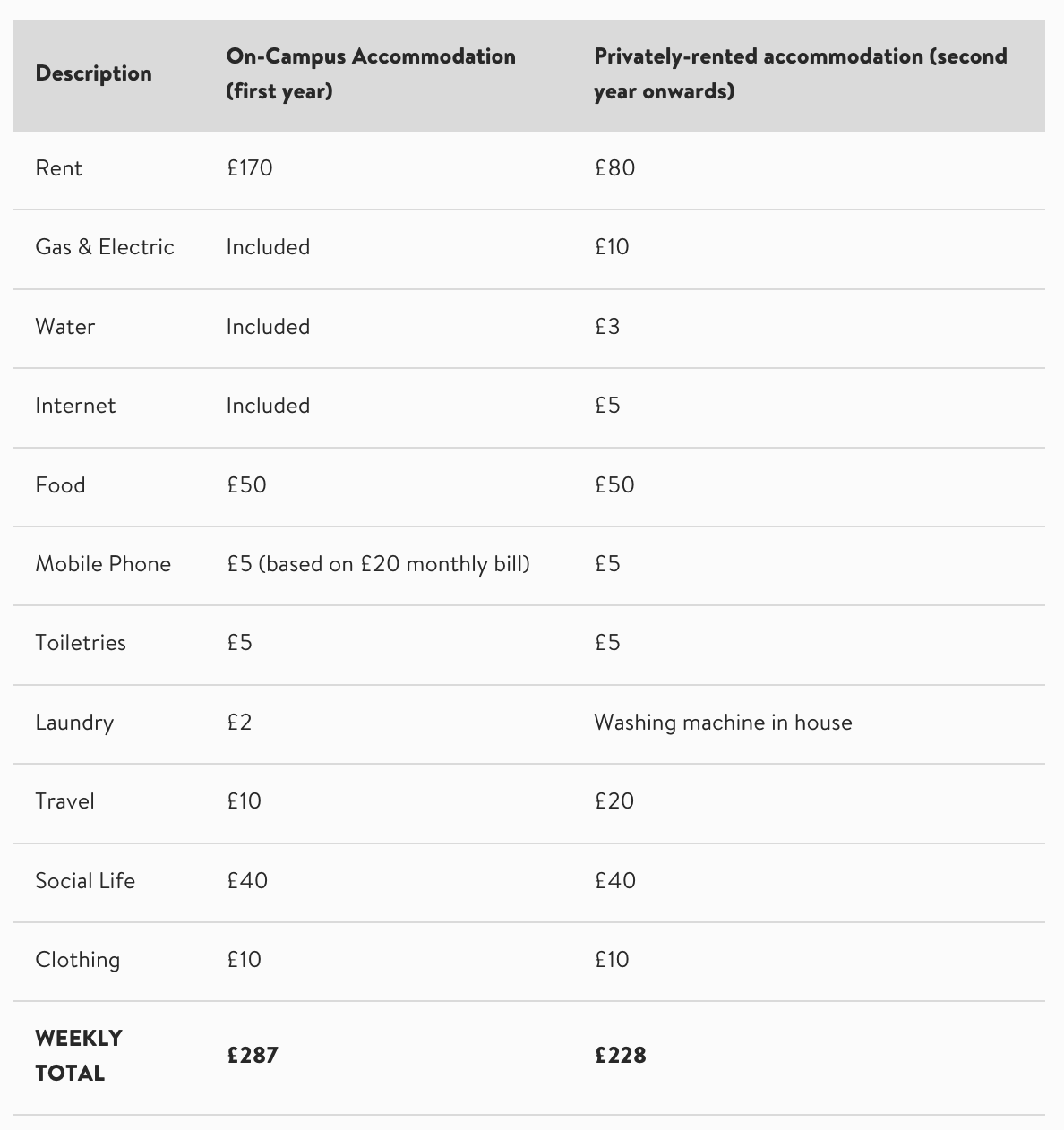

Meanwhile down in the South West, one university has tables that “give a good idea of the average term-time living costs” for a first year:

The good news is that the pricing for accommodation and food has been updated. The bad news is that the rest of the costs haven’t been touched since at least 2015, when this table appeared in the undergraduate prospectus:

And if we compare the 2021 iteration to now, the only thing that’s changed is the price of accommodation and the TV license:

That university – like many others – also refers readers to the Which? Student budget calculator, which was deleted in 2022 and even when live was last updated in 2019.

Team players

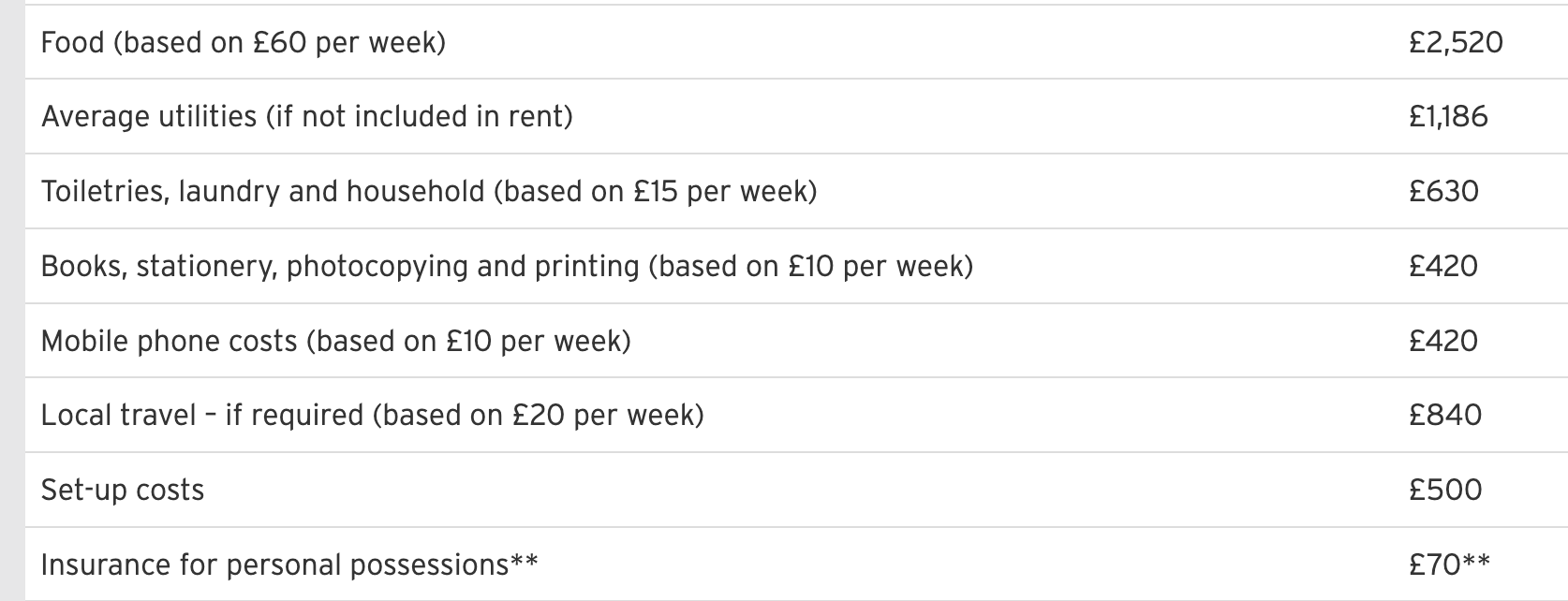

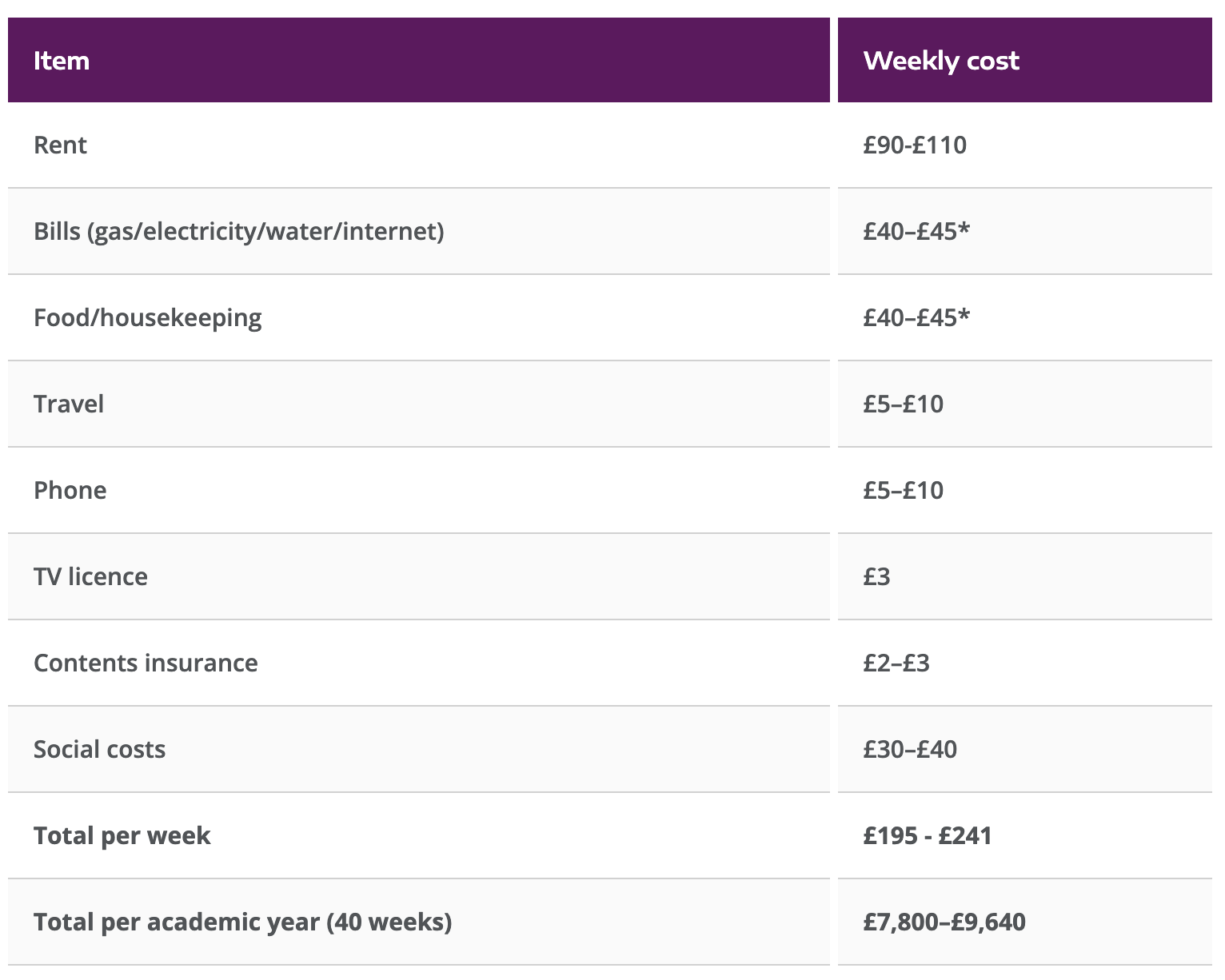

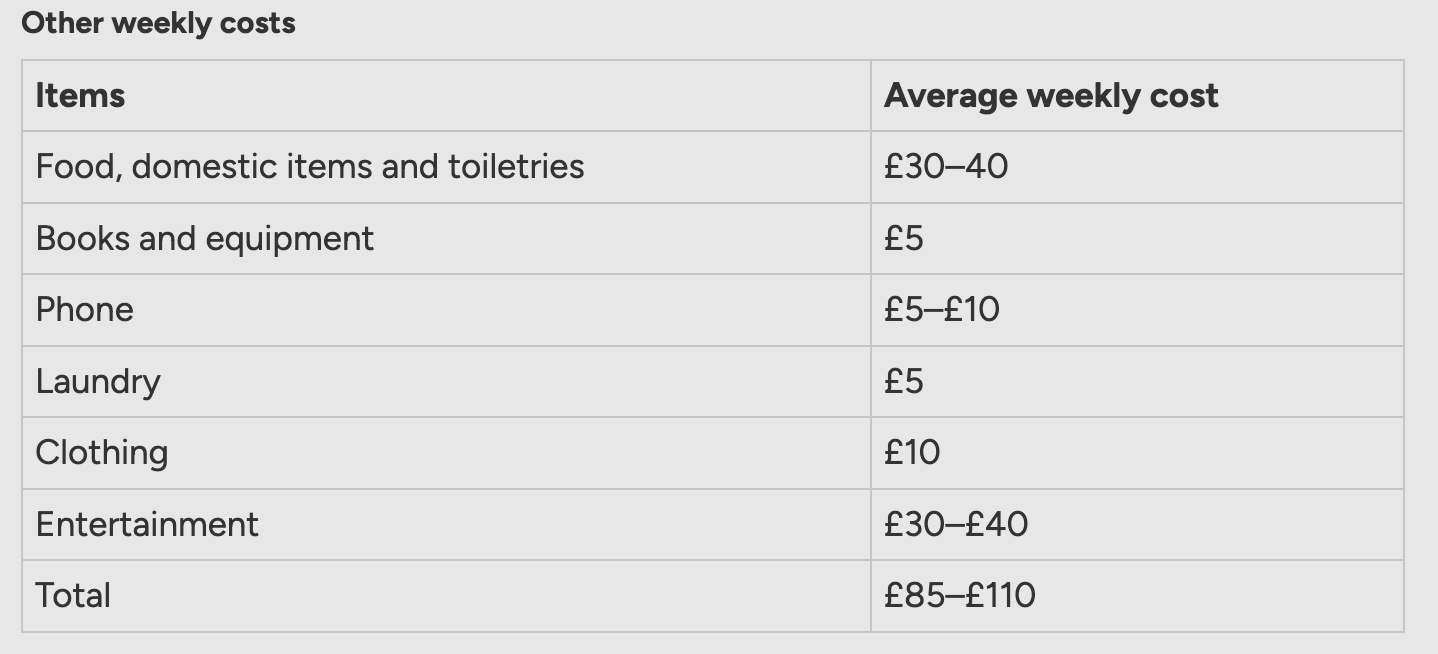

Often the numbers in the tables aren’t sourced – and read like there’s been a chat in an office. So in Yorkshire and the Humber, one university reassures readers that the “minimum costs” for 42 weeks in 2024/25 in its table “have been estimated by our support teams”:

They may well have been, but those support teams appear not to been experiencing inflation since 2021/22:

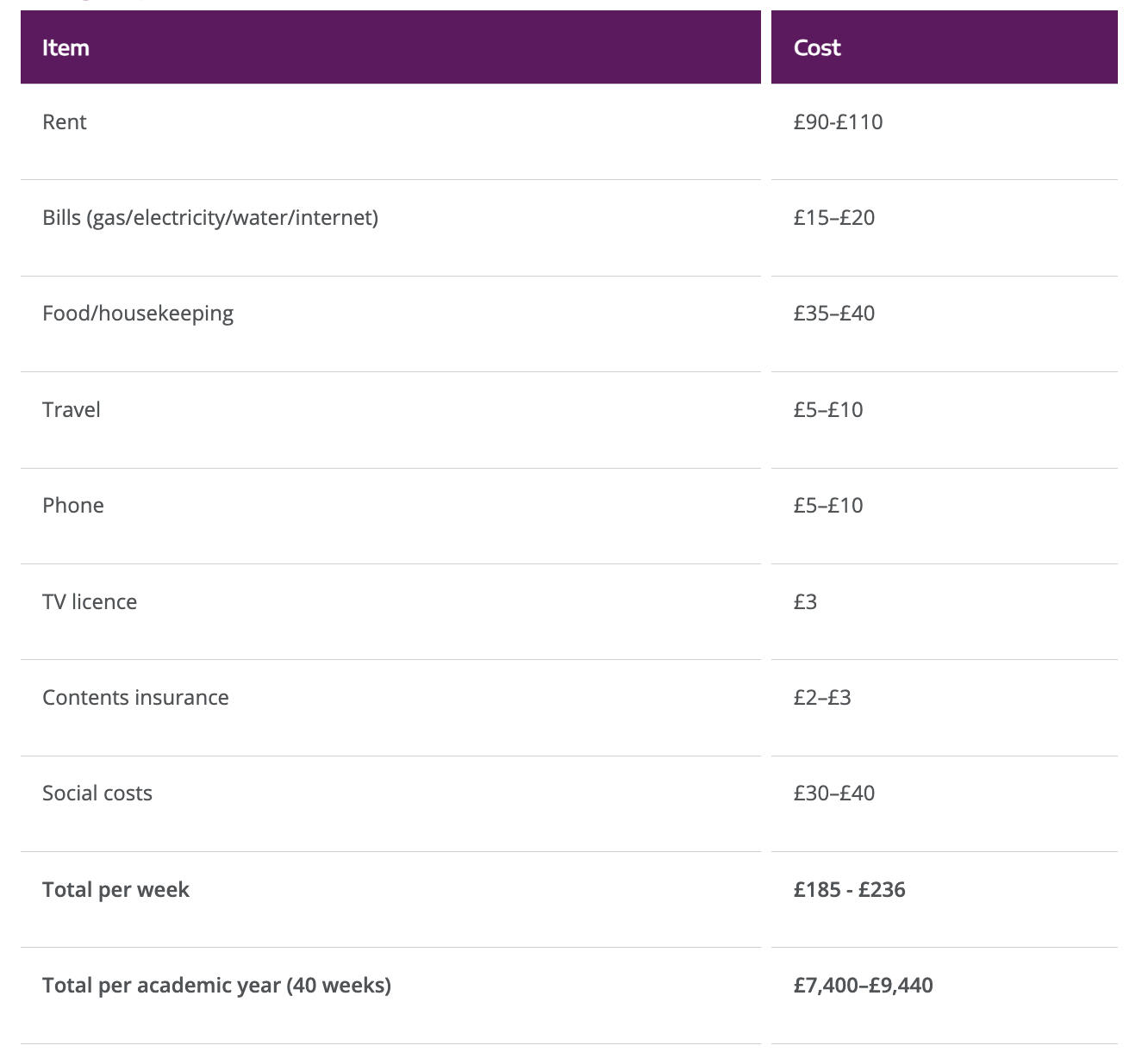

In the South East, one university advises prospective students that to be able to create an accurate budget, they need to be aware of all the costs they will incur over a year. Its table – here in 2024 – advises students of the cost of university student residences in 2021, and has other figures unchanged from when the top of the table referred to student residence costs in 2018:

Actually, to be fair, the cost of “toiletries, laundry, etc” has gone up by £2 in the estimates – most students being blissfully unaware that the cost of such services is usually set by the universities themselves on commission kickback deals.

Computer says this

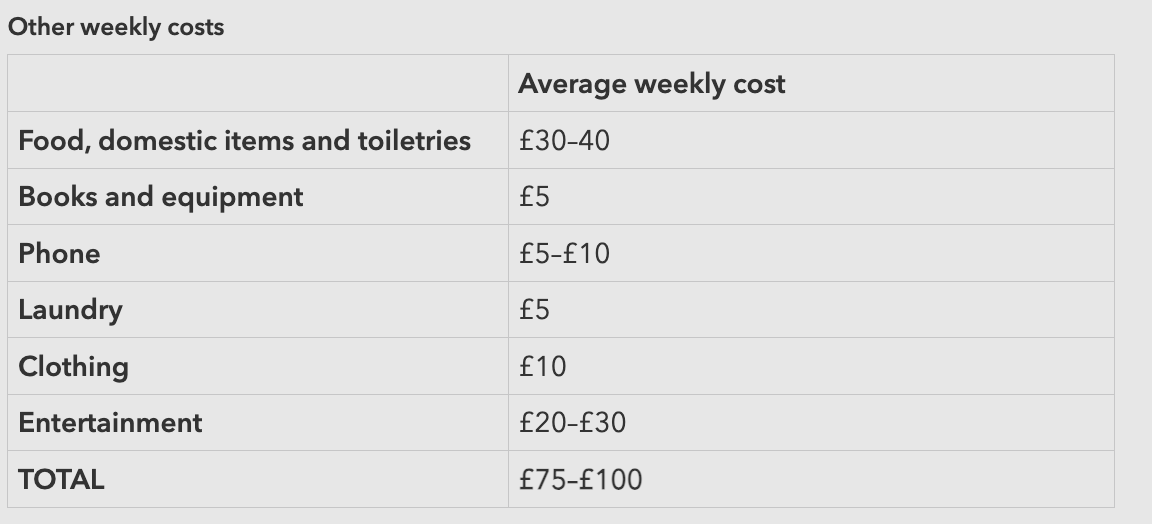

At another university in the South East, prospective students are told that supplied figures are “based on sector averages” (what are these mysterious averages), with some variations based on local costs “monitored by our Student Finance Centre to ensure the figures accurately reflect the true cost of living”:

It’s not especially clear how often that “monitoring” is happening, because most of the numbers are magically unchanged since 2020:

Sometimes there is a source – and one of the common ones that gets referred to is Save the Student’s Cost of Living Survey:

That, lest we forget, was a survey where half of respondents said financial issues were impacting their diet, 55 per cent said they were impacting their mental health and 6 in 10 said the lack of money was hitting social activity.

That’s the problem with quoting figures from surveys on what students are actually spending. Even if the sample size is robust, it’s hardly great advice to be telling students they’ll only need what people before them spent – especially when 30 per cent of the people before them said money issues were causing them to lose sleep.

Back in the North West, another university “advises” students to budget a minimum of £9,207 for each academic year of undergraduate and postgraduate study – an amount that “should cover” accommodation, food, entertainment, transport, books, insurance and other living expenses.

That’s the amount the Home Office says that international students need to be able to show as “proof of funds” to enter the country. It’s also a figure that hasn’t been updated for several years – so international students relying on it as a budget figure are likely to get into difficulty.

To be fair to this university, it also says that “the living costs mentioned above are a guide”, and that some students will require more than this, “depending on lifestyle” – with a link to a page on typical costs in the city.

Sadly that page has figures that are eerily similar to the figures the university was publishing bac in 2020:

Federal aid

If a student from the USA needs to access federal aid, the “Cost of Attendance” is the maximum amount students are able to borrow, and includes living costs based on a university’s calculations.

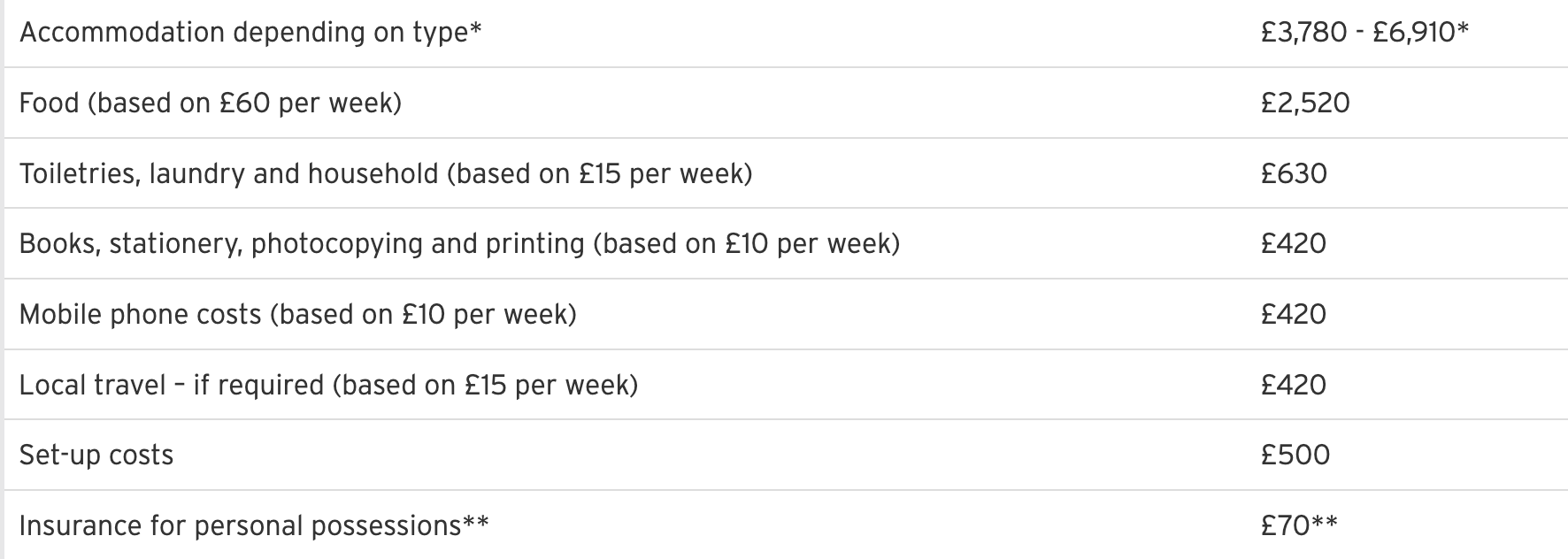

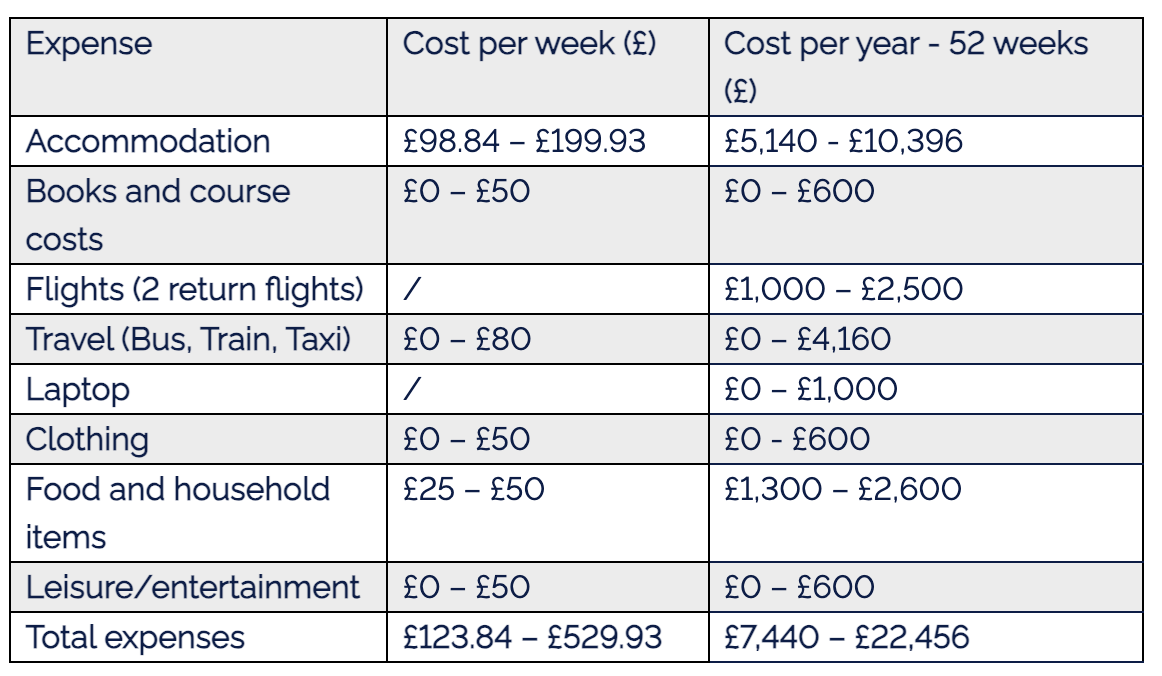

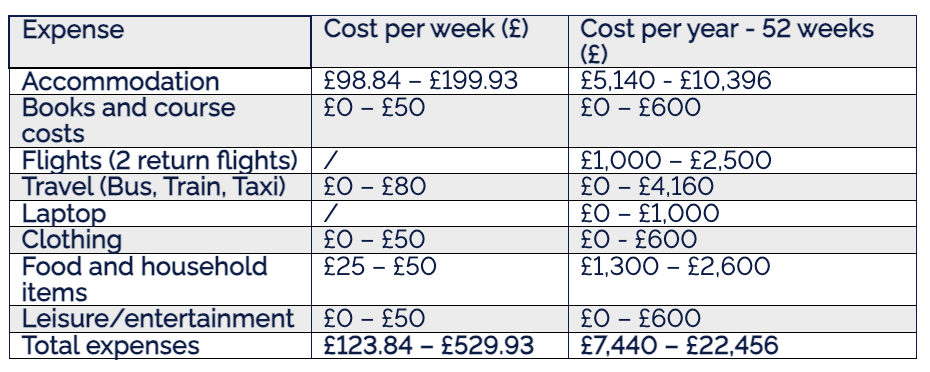

One university in the East of England calculates its CoA as follows:

Sadly it’s not a page that it’s updated since 2021:

As a result, even the information on visa fees is wrong:

You may recall that a while ago, HEPI published a paper that sought to identify a Minimum Income Standard (MIS) for students. It put figures on how much money students need not just for clothes, food and rent but for full participation in university life.

It said that students need £18,632 a year outside London and £21,774 a year in London to meet MIS. Vanishingly few universities quote anything near that – but you might have expected the university whose academics delivered the research underpinning the MIS to be closer.

It is closer – but it’s still £2k short outside of London.

Another university says that budgeting isn’t just about seeing how much money you will need to pay for your food and rent – it’s a “really good way of working out how much you can spend” on “things you enjoy”.

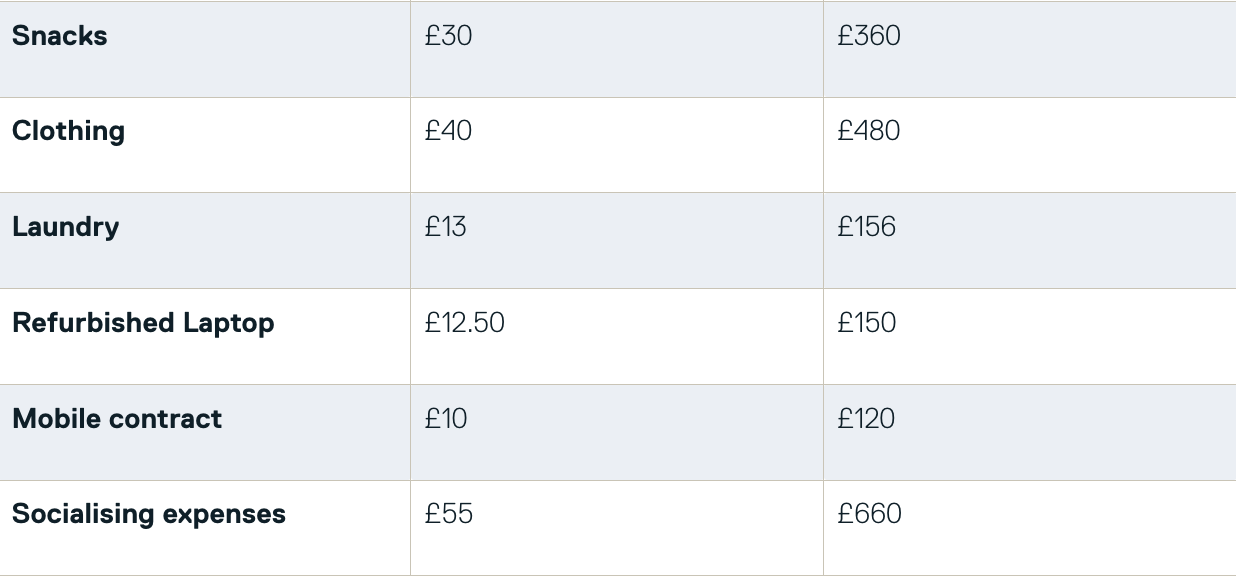

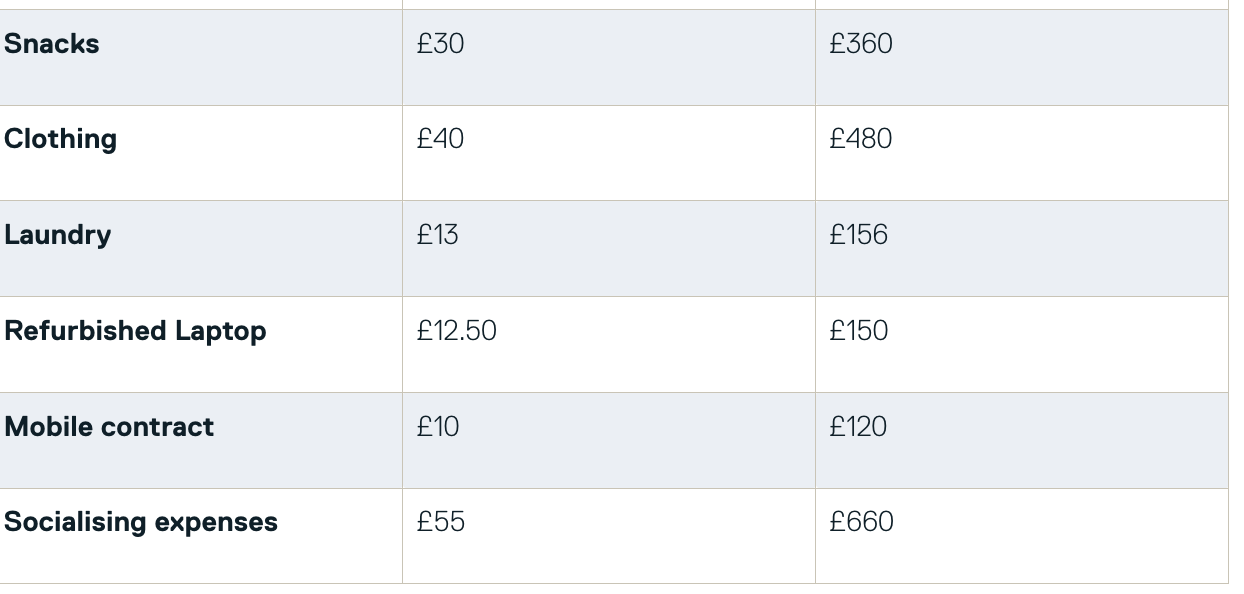

To assist, it lists a range of living costs:

…the only one of which that has been updated since 2020 is “entertainment”:

Beth knows

It’s tricky stuff this. Some universities used to mention likely costs but seem to have given up. Here’s what one university in the East of England used to say in 2022:

That’s gone now, and instead applicants can watch a video where they can “Budget with Beth” instead:

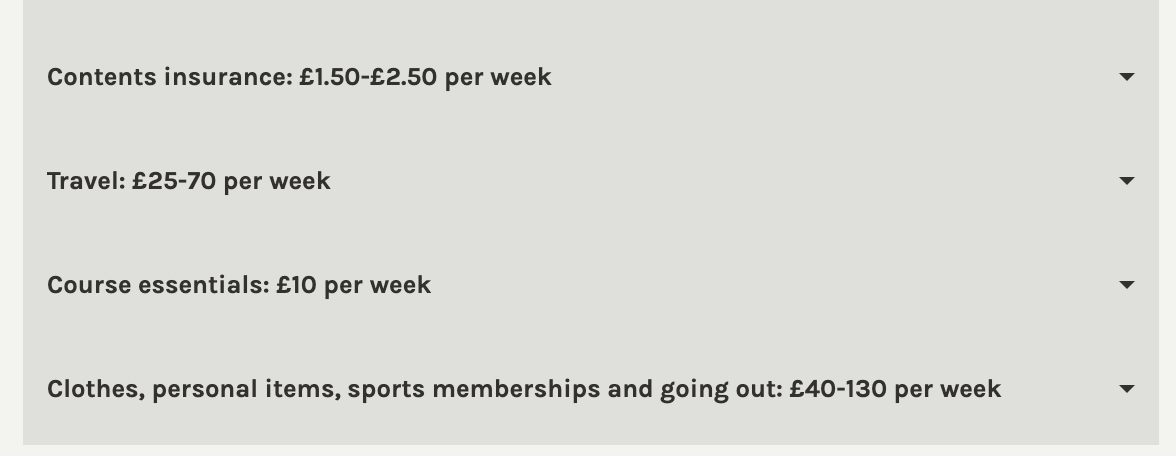

The capital can be pricey. One university says that being in a “large and potentially expensive city like London” means that on average, students “can spend around £475 per week on rent and living costs”.

That’s the same figure it was headlining with in 2022, despite some of the components going up since – although apparently, next year its students will pay the same that they did 2 years ago for contents insurance, travel, course essentials, clothes, personal items, sports memberships and going out.

And some universities brag about their position in whatever league table is around on cost of living. These both trumpet their places in the NatWest Student Living Index – the exercise that in 2021 told us that students in London were paying £9.10 a pint, in 2022 suggested student rents in Edinburgh had fallen to £200 a month, and last year claimed that the average number of hours students were spending in part time work each month had decreased from 43.16 to 18.3.

I find myself, head in hands, just begging anyone who’s got this far to do what I suggested this time last year.

Look at your university’s information. If there are figures, ask where the figures come from. Ask if they’ve checked with real students (how any university in England with an access and participation plan gets away without doing so is beyond me).

Ask those responsible to find a way to collaborate with others in your city or region to get some accurate costs information – avoiding the often wildly different estimates that sometimes apply to the same places.

Urge colleagues to be more like Swansea – which says out loud that it has “seen many students arriving who have unrealistic expectations of living costs” and goes on to offer all sorts of helpful information.

Remember that costs differ by programme or subject of study. Remember to warn students about inflation – core CPIH is still up at 4.2 per cent, for example. Treat cost of living information as a series piece of IAG, not an opportunity to sell your wares.

Real budgets, of course, would include other things. Money for being ill which is expensive. Travel money to go “home home” when support dictates. All those hidden costs buried on other webpages. Money to replace things that go missing – cutlery, coats, phones. Real life. It’s why that HEPI work on a MIS is so important. Why not just quote those figures? What are you waiting for – someone else to do it in case it makes your place look bad?

But at this point I’d just take some semblance of accuracy and coordination across cities.

Above all, ask yourself this. In a drive to get people to come, and to come to us, have we made it sound just that little bit too easy? It’ll save all of that snogging later.

Taking just one example (the East of England one above): ultimately, it is misleading, as the average housing costs where they are based will never hover near that lower limit. And prospective student marketing, including for the majority of international students, does not provide this information (aimed just at Americans making federal loan applications). For one of the campuses this university has, the *average* cost of rent in the very limited uni accommodation at that university is £190 per week – the uppermost end of their projections (a third of those options being over £200). Private accommodation is under high… Read more »

The problem with this article where the content has been tortured to fit a hook, is that the central hook gives rise to nonsensical bullshit: “The cost of living crisis has some similar options. Snogging cozzy livvs is about hardship funds and free breakfasts, marrying is about getting costs for students down (or at least loaning them enough to live on), and avoiding is about being upfront about costs in that city so that students can either choose a different one, or at least save up sufficiently.” What does this abomination of a paragraph even mean? Imagine thinking this applies… Read more »

Thanks Martin. That’s a description of the use of the categorisation that seems to have worked to set up the exercise on policy choices for hundreds of teams of sabbatical officers in SUs over the years, but it obviously hasn’t worked for you. Do you have an alternative suggestion?

Unfortunately you have de-anoned the university “down in the south west” by reproducing the 2015 table in the distinct font that institution used for its materials at the time. Or maybe other people aren’t paying attention to university typography as closely as I am.

I greatly admire your attention to detail – as someone outside of the English HE scene, my guess for use of that particular font would’ve been John Lewis! You may be the only one in the know, guard their secret 🙂

I think the OfS should force all Universities to show the Hepi compiled figures on their websites with the option of also showing an individual, local University calculated figure, if they wish, that can be easily proved to be the truth.

Perhaps Universities UK could commission Which? magazine to provide the figures instead.