In a week focused on multiple facets of the work to enhance access and participation one of the major talking points has been how accurately to take account of an individual’s circumstances in order to contextualise their attainment and make an assessment of their merit and potential.

We believe UCAS’s multiple equality measure (MEM) could be the answer to a lot of the challenges to the area-based measure POLAR that have been raised recently, for example in this article for Wonkhe by Stephen Gorard, Vikki Boliver and Nadia Siddiqui.

We are all individuals

To go back to first principles, everyone, no matter where they’ve grown up, what school they’ve been to or what their parents have achieved, should have a fair chance of getting into their chosen course at university or college. Everyone is an individual and a single statistic can’t define an individual student. And yet, when measuring fairness in access to higher education, one piece of data is frequently used above all others. A student’s home postcode.

While the POLAR measure has been regularly developed to keep it as up to date as possible, it is still based on how many people from surrounding homes have gone onto higher education. A multidimensional assessment of equality in admissions, the MEM takes account of many intersecting aspects of inequality and reduces the risk of disadvantaged applicants not being identified.

There is a risk that decisions based solely on POLAR may lead lead to an incomplete judgement being made about people. Take the third quintile, for example. It’s in the middle of participation rate data and can be awkward to use in assessing the probability of members from this group accessing higher education, as students from quintile three are often deemed neither advantaged nor disadvantaged. In fact, almost 10 per cent of these students are white males who receive free school meals – characteristics which are typical amongst groups showing the lowest progression rates to university.

Introducing the MEM

MEM is based on sophisticated statistical modelling techniques, using UCAS’ data on progression to higher education, linked with National Pupil Database data on English school student characteristics (POLAR quintile, ethnic group, gender, free school meals status, Index of Multiple Deprivation and school type) to produce an evidence-based measure of equality at both an individual and aggregate-level. While MEM is currently England-specific, we’re working with devolved governments to expand the MEM across the UK. Additionally, as we develop MEM we will look at the feasibility and value of adding in further individual level variables, of which care leaver may be one.

The MEM is now UCAS’ principal measure of equality and is used for reporting progress on entry rates to higher education. Similarly to POLAR, the MEM aggregates a student into one of five groups, with group one containing those least likely to enter higher education, and group five those most likely.

POLAR paints too rosy a picture

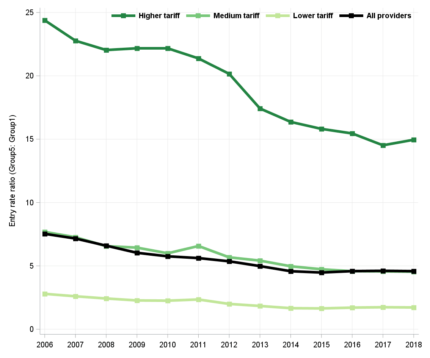

Our analysis shows that while the POLAR gap in entry rates has continued to narrow slightly in recent years, it has remained almost static in MEM over the same period.

Our end of cycle report for 2018 shows that the entry rate of students in MEM group one (the most disadvantaged group) increased by 0.9 per cent proportionally, to 12.3 per cent in 2018. This was three times the increase seen in the entry rate of students from MEM group five, which rose by 0.3 per cent proportionally to 56.3 per cent. The large difference between entry rate in these two groups, the most and least disadvantaged in our society has thus changed very little. For 2018 the ratio of entry rates between groups one (most disadvantaged) and five (least disadvantaged) and has only shifted from 4.61 to 4.58.

The MEM equality gap is most pronounced at higher-tariff providers, where in 2018 the most advantaged students were 15 times more likely to enter than the most disadvantaged, and 2018 was the first year the gap has widened.

It’s also important not to ignore the individual factors which can’t be picked up by any statistics and are often self-declared information in a UCAS application, for example, as part of a student’s personal statement, or in their supporting reference. Information found here needs to be used to recognise the potential of students whose personal circumstances may have restricted past achievement.

UCAS support for contextual admissions

UCAS is already supporting universities and colleges in their efforts to widen their applicant and acceptance pools. During the 2018 admissions cycle, we worked with thirteen universities to test the feasibility of using a new way of contextualising admissions. Our modernised contextual data service (MCDS) provides individual-level MEM data as well as a context-adjusted grade profile for each applicant. Following its success last year, twenty five universities are using MCDS.

This is in addition to our existing and widely used contextual data service which includes historic data, going back to 2008, about an applicant’s school or college supplied by education departments across the UK. It also provides local area data in the form of POLAR and the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

It is positive that the Office for Students Insight briefing on use of contextual in admissions uses the MEM as a key measurement. I hope that colleagues across the sector see its potential to be used as the definitive measure to drive forward progress in closing the gap in access to higher education.

The problem with focusing on a single measure of disadvantage – whether it is POLAR, the UCAS MEM or something else – is that inevitably the focus of funding and accountability measures shifts to that measure alone. Two examples. One issue with POLAR is that those from ethnic minorities are only half as likely to live in POLAR Q1 than others and so an unintended consequences of focusing resources and university accountability on POLAR Q1 is a lack of support for ethnic minorities and an inability to tackle the massive “fair access” gaps by ethnicity in access to the most… Read more »

Hi Pete, thanks for your interest in the MEM. The MEM is itself is a combination of several measures, which come together to create a value between 1 and 5, taking the various characteristics into account.

You might find the visual interactive tool on this page of our site useful – https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/ucas-undergraduate-releases/ucas-undergraduate-analysis-reports/equality-and-entry-rates-data-explorers

There are also summary (https://www.ucas.com/file/190246/download?token=7drEUmCm ) and technical reports (https://www.ucas.com/file/190241/download?token=TrHwfBmw ) published in October.