Open Data, data that’s available to everyone to access, use and share, has risen to prominence in the UK government agenda and across the globe in recent years.

In 2012, the inventor of the web Tim Berners-Lee co-founded the Open Data Institute to advocate for the worldwide adoption of open data, and in 2013 the UK government followed suit, placing open data at the centre of its strategic thinking set out in the digital strategy.

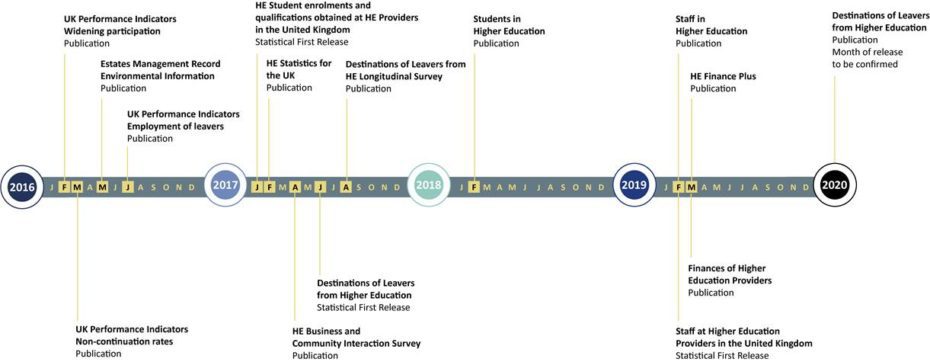

The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) has committed to publishing all possible data as open data by 2021, and they’ve already made a start. Wonkhe spoke to Jonathan Waller, HESA’s director of information and analysis who is heading up the agency’s open data strategy, to find out how it’s all going and how they’ve found the process so far.

Opening up your data has made it easier for us to analyse what’s going on in HE for our readers. Why now?

Our exploration of open data has been going on for a little while now. We became increasingly aware of the open data agenda and the direction of travel within the UK, particularly driven from central government in 2015. We were also involved with a project led by Universities UK, called “Creating value from open data” and through this gained an understanding of the different aspirations and support for open data. The same year, Paul Clark, then-UUK director of policy and a senior lead on their open data project, joined HESA as chief executive. He was a strong advocate for open data – that was the catalyst for us to commit to change. Early in 2016, we started to frame our open data journey.

What are some of the difficulties associated with making the transition to open data?

One of the initial challenges for us was about building our knowledge and understanding of the practical requirements of open data. Support from The Open Data Institute has helped us to achieve that.

The most recent aspect we have been looking at is the issue of machine readability – what it means and how we can optimise it to best facilitate reusability of our information. A real challenge we’re facing is how we deal with the fact that much of the most used data is data on staff and students which is sourced from personal data. There is a tension between our desire to widely publish our data as open data and the need to maintain the confidentiality of the individual data subjects. We already use disclosure control techniques – like rounding counts of students and staff to the nearest five. But when we are looking at publishing quite extensive sets of detailed data as open data, the application of that kind of disclosure control approach can work against utility and reusability of that information. Clearly, with a large and detailed dataset, you’re dealing with many rows of data that might relate to just one individual. Rounding each row count to the nearest five would mean that these would round to zero. Data users then analysing and aggregating the data would end up with some very inaccurate counts of students or staff numbers – hence the use of this disclosure control would have a destructive effect on the utility of the data set.

What steps are you taking to make sure people can understand your data and use it responsibly?

One of our aims with open data is to appeal to a much wider range of users. Many of our existing users are quite expert in HE and in using HE data, and as we want to open up that appeal, we need to look at ways of ensuring that new users can understand the information and are able to apply that information effectively and responsibly.

Recently we have adopted some quite different approaches to how users navigate through the range of information that we publish. The information we’re publishing now is far more interactive, and it’s framed in terms of the kinds of questions users may want to ask about higher education, such as – where do students come from? And where do they study? We then frame sets of data, visualisations and charts around those themes. That, we hope, makes the information more accessible to non-expert users.

We’re also trying to rethink the way we explain the information in documented format on the website. Whereas previously we would tend to have quite large, weighty documents which list all of the different data definitions and all of the different quality issues that users need to be aware of when using the data, we’re now trying to redesign that approach so that we have bite-sized chunks of key explanations embedded in the material we publish, written in quite an accessible way. We have more in-depth definitions for the more technically capable, who need the full detail on particular types of data. It’s about different approaches to explain the data for different types of user. This is an area where further work is needed, and we’re looking for user feedback on the different approaches.

What – if any – measures do you take to ensure that your data can easily be reused alongside other common sector datasets (eg HEFCE, UCAS, SFC)?

The key issue is around data standards. If we can ensure that users who are exploring and utilising different sets of data have confidence that similar data concepts within those are described in consistent and comparable ways, using coding frames and definitions – that goes a long way to enabling the combined use of those datasets and the linking of those datasets together.

We’re a strong advocate of data standards, and we work closely with a number of other sector organisations on those data standards. I think that’s one of the key elements that will ensure that a number of datasets are reusable together.

Have you noticed a difference in impact?

Yes – with the most recent student data, within 24 hours of releasing it we saw a number of users reusing and re-presenting the information in interesting and novel ways. The most gratifying thing for us was to see the data being actively used. This year we saw the level of page hits almost double from last year’s edition of the equivalent statistics. We’re seeing significantly greater levels of usage of the more interactive data formats we are now using.

Will you be committing to using and fully documenting open standards for sector data, including identifiers?

One element of this is about our use of existing data standards. We have long been advocates of utilising existing data standards where those are suitable for our uses, and that’s part of our approach to data collection. Examples of this include national and international standards around country codes, UK provider reference numbers and census classifications for ethnicity. All of those are incorporated into our data collections. However, there are also areas where there may not be existing data standards which we can utilise, so we’ve long had to create our own coding frames and definitions for certain types of data. Where we can, we’ve done that working in partnership with key sector bodies. An example of that would be subject classification.

Do you think we are moving towards a future of open data across higher education and other sectors? Why?

Yes I do. There’s clearly a strong direction from central government to move towards open data. The idea of moving to open data by default is an increasingly strong theme within the context of different government departments and related bodies, in particular. It also aligns with what we’re seeing in many other countries as well. The move to greater transparency is very much an international one.

There are questions as to where and how the increasing marketisation of higher education might interact with the drive for more open data. If we look at highly competitive sectors elsewhere, there is often less willingness to expose and share operational data between organisations. In particular, there’s the issue of perceived commercial sensitivity of information. It would be a huge shame if the level of transparency and willingness to share information for the common good that we’ve seen for decades within the UK HE sector were compromised by that. I’m hopeful that this won’t be the outcome, but it has to be seen as a risk.

You can read more about HESA’s open data strategy here.