I’m in two minds over whether it was a curse or a blessing – and I may be retrospectively overstating its impact.

But when I sat down to watch a bit of telly back on Tuesday 13th May 2003, I had no real sense of the extent to which it would end up causing me lost sleep over silos.

The Day Britain Stopped was a BBC1 docudrama, set in the near future, that explored how a devastating chain of events could leave the country completely paralysed.

First, a national rail strike pushes huge volumes of passengers and freight onto the roads, overwhelming the motorway network.

Then the M25 becomes jammed after multiple accidents, including one on the Dartford Crossing. Poor coordination between highways management, police, and emergency services slows response times, and conflicting rerouting decisions worsen the congestion, leaving rescue crews unable to reach incidents.

Then severe delays ripple through the air transport system, compounded by diverted flights and congested airports. And these all lead to a mid-air collision between two aircraft near Heathrow – killing hundreds – as communication and coordination systems fail under strain.

Gridlock

I was thinking about The Day Britain Stopped on a campus a few weeks ago. Student leaders were explaining a proposal from their university to take 30 ECTS credits or so of most degrees (ie a semester) and turn them into a compulsory placement.

A “mini sandwich” is not, all things considered, a terrible idea. Students would gain valuable work experience – which we know helps with graduate outcomes – and in aggregate there would end up being a moderate reduction in teaching and assessment costs.

But on the assumption that it would often be unpaid, given the maximum maintenance loan is now significantly below the National Minimum Wage (when chunked out at 30 weeks for 35 hours a week), working full-time for a semester would pretty much prohibit students from earning the extra that many need to now.

Just like the two teams each re-routing traffic down the same country lanes around the M25, it’s a classic case of not seeing the full picture – and when combined with the HE sector’s preference for policy over scenario planning, potentially disastrous. But nothing like that could be coming in the year ahead, surely?

Britain’s best days are ahead

This does nothing for my doom-mongering street cred, but back in May 2024 – when HEPI and TechnologyOne published work from Loughborough University on a Minimum Income for Students (MIS) – I allowed myself a little optimism.

In a sea of information that seemed to be designed to entice participation rather than be realistic about the costs of it, I imagined that the headline figure – that students need £18,632 per year outside of London to achieve a baseline student experience – would start to adorn .ac.uk cost of living webpages offering budgeting advice to students.

Given the methodology for calculating the MIS was close to that used by the Living Wage Foundation, and given the Westminster government’s intent to ask the Low Pay Commission to (to all intents and purposes) replicate that methodology for the National Living Wage, I even allowed myself to imagine for a few moments that government might commit to closing the gap between available support and liveable income. It surely wouldn’t be committed to a liveable income for work but not one for study?

Alas, it wasn’t to be. Vanishingly few of the universities that offer “typical” or “sample” student budgets quote anything like that figure – and that’s if they offer one at all. International students are still misled into thinking that the maximum maintenance loan will cover their costs, parents are still completely in the dark about what they’ll really need to contribute, and many of the survival stories that I’m told by new student leaders every summer have gone from amusing to heartbreaking.

The MIS report even recommended that when students apply to higher education, UCAS could compare the support available from the student’s home UK nation with their expected living costs. But at the time of writing, the admissions service’s webpage on budgeting instead offers “average” spend figures from 2020, and somehow omits the £2,110 that the source study found students spending when preparing for higher education.

Governments, meanwhile, did little. This coming September, Scotland is offering up a freeze (real terms cut) on maintenance support, Northern Ireland has an increase that still falls significantly short, and both Wales and England are increasing the maximum by 3.1 per cent. A frozen means test threshold means even fewer will get that max in England – and right now both RPI inflation and CPI inflation are in fact running at 4.1 per cent.

Update: It’s all worse

As such, if last year’s report was like a warming sign, the 2025 update to the MIS report ought to be like a fire alarm. The update expands on the 2024 research by examining first-year students and those living in halls for the first time – and through focus groups across five UK cities, researchers found that first-year students face the highest costs of any student group – £418 per week including rent to reach a minimum acceptable standard of living.

This represents a “first-year premium” of around £14-20 more per week than continuing students, driven by both “setting-up” costs (laptops, kitchen equipment, bedding) and “settling-in” costs (freshers week activities, food wastage while learning to budget, and higher social spending to establish friendships).

The financial pressure on students has intensified dramatically across all UK nations. In England, even students receiving maximum maintenance support can only cover half (50 per cent) of their actual living costs, forcing them to work over 20 hours per week at minimum wage to make ends meet.

That, I add in passing, is 20 hours more a week than most politicians’ alma mater allows students to work to have a fulfilling student experience:

Studying at Oxford is an exciting experience with plenty of opportunities and a high number of contact hours. For this reason, paid term-time employment is not permitted except under exceptional circumstances and in consultation with your Tutor and the Senior Tutor.

Students from different UK nations face different circumstances – Welsh students have 63 per cent of their costs covered by maintenance support, while those from Northern Ireland receive support covering just 42 per cent of their needs. The gap between what students need and what they receive has created what the researchers term a “hidden parental contribution” – one that now exceeds £10,000 annually for English families.

I still regularly encounter those who expect to see mass dropouts as a result of the growing gap – but anyone that works closely with students will tell you that it’s a slow participation implosion that we’re seeing rather than a non-continuation explosion.

Two-thirds of students now work during term time, the highest on record – pressure that is squeezing out various aspects of university life, as students report less time for independent study, fewer opportunities to join activities, and increased commuting distances. Many are experiencing a fundamentally different university experience than they expected, with a third having less disposable income than planned, and 1 in 5 buying fewer books or course materials.

Over a three-year degree, the total cost of reaching minimum living standards ranges from approximately £59,000 in Wales to £77,000 in London, excluding tuition fees. And these figures are what students need not for luxury, but simply to participate fully in university life with dignity. Even living in accommodation that is “purpose built” for students, while providing important social opportunities, is typically more expensive than shared private housing – with rent making up to 47 per cent of total living costs in London.

Thanks to Terry Nutkins, Gordon Banks and Let Loose

One particularly pleasing aspect of the report is the “surprising” costs that so many miss when casting round the marcomms office for a couple of student ambassadors to cobble up a budget.

Practical necessities include storage costs between academic years when halls contracts end, insurance for phones and laptops used outside accommodation, and mattress protectors for the “really cheap and uncomfortable” beds typically provided.

First-year students face particular financial pressures during their settling-in period, wasting money on food while learning to shop and cook independently, plus ongoing laundry costs in halls that can reach £5 weekly for basic washing needs.

Academic periods bring additional expenses, from extra food costs during exam sessions when students spend long hours in libraries, to transport costs for third-year students attending job interviews and graduate recruitment events.

Basic costs related to social participation and mental health are also included. They include individual crockery and cutlery in halls to avoid hygiene issues when sharing with strangers, a £20 (!) annual personalisation budget for room decoration that prevents students feeling like they’re “in prison,” and £50 annually for clothing required for university social events and society activities.

They are seemingly minor expenses – but they all add up, and they highlight how the “minimum” standard isn’t about luxury, but about enabling students to participate fully in university life, maintain their mental health, and avoid social exclusion.

There’s also dehumidifier packs to combat poor ventilation and condensation from drying clothes, tabletop ironing boards to fit cramped spaces, and overdoor hooks because standard furniture is insufficient for storing belongings across shared living arrangements.

Technical necessities include extension leads for inadequate electrical outlets and Wi-Fi boosters for poor connectivity, while protective measures like upholstery and carpet cleaners become crucial for avoiding deposit losses. Even basic items like door mats for communal cleanliness and shower caddies for bathroom storage represent additional shared costs when five people live together.

Beyond accommodation, students face numerous individual costs related to campus life and practical necessities that all accumulate quickly. They include water bottles and Tupperware containers for daily campus use and food storage, delivery and returns costs reflecting modern shopping patterns, and small airers for bedroom clothes drying when shared facilities are limited.

Admin costs like provisional driving licences at £34 become the most practical form of student ID, cheaper and more portable than passports. And there’s eye tests every two years with potential glasses purchases, and a small budget for everyday medicines and a couple of prescriptions annually – along with significant variations in personal care costs, the report particularly noting “the higher cost of hairdressing for afro hair in particular,” while emphasising that regular haircuts are deemed essential for being “presentable” and maintaining “self-respect”. Luxuries these are not.

Parental contribution

The report repeats last year’s calls for urgent, system-wide reform based on five principles: simplicity, transparency, independence, sufficiency, and fiscal neutrality. Key recommendations include increasing maintenance support so students can reach minimum living standards through a combination of government support and reasonable part-time work, providing a “first-year boost” to help new students establish themselves, and raising parental contribution thresholds so families only contribute when they themselves have achieved minimum living standards.

The researchers argue reforms could be implemented without additional government spending – although the proposal is to reintroduce much-maligned but fairly progressive real interest rates on student loans, ensuring those who benefit most from higher education contribute accordingly. Sadly, they’re usually the loudest too.

Without reforms, they warn of three critical risks – increasingly unequal access to higher education, declining quality of student experience, and threats to sector sustainability as students struggle to afford university attendance.

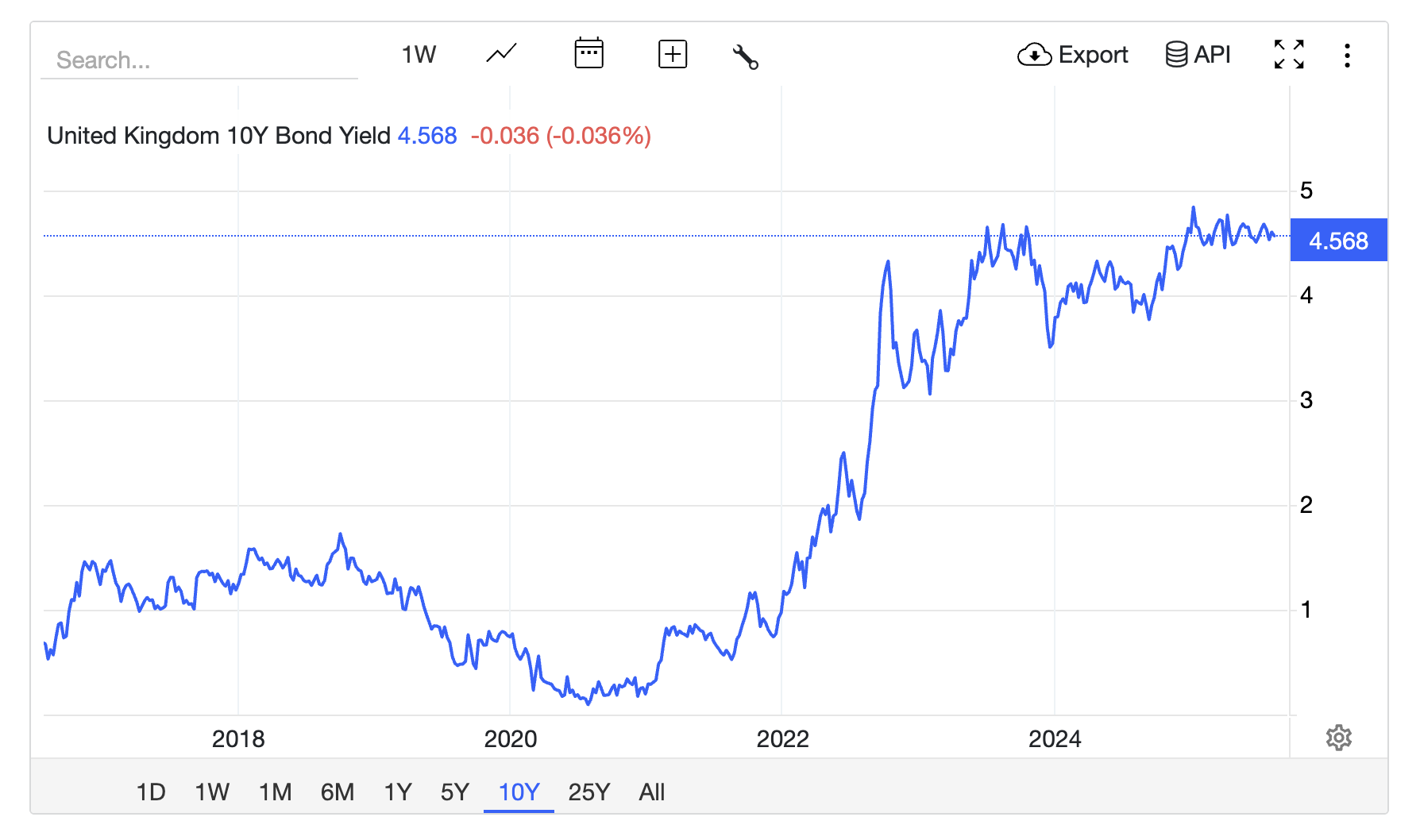

But forgive me for the doom. Any or all of that will have to wait until at least September 2026, and even then is looking increasingly unlikely, given that the Treasury is said to be staring at a £41bn hole in its budget, and is currently borrowing the money on the bond markets to lend to students at an interest rate of 4.5 per cent – a far cry from 0.5 per cent nine years ago.

And it could all be about to get much much worse.

Basket cases

Whether you use RPI or CPI is almost immaterial – it’s the basket of goods that matters, and neither basket captures the basket of a student typified in the MIS. Students spend more on food than the average consumer, and in that basket they’re less able to “trade down” through the brands.

The Bank of England expects food inflation to be around 5 per cent Q3, rising to 5.5 per cent by the end of the year – higher global commodity prices, higher labour costs and Extended Producer Responsibility regulations that come into effect from October of this year all driving the change.

In June, Beef and Butter were up at 20 per cent, Coffee was at 12.5 per cent and Chocolate was running at 16 per cent. Decent rent data is hard to come by – but it always seems to increase by more than inflation. If not included in their rent, energy prices have shifted from being a drag on inflation to providing a boost – Ofgem’s price cap for households is £1,720 for July-September 2025, almost 10 per cent higher than the same period last year.

And the BoE’s key mitigation measure – to cut the Bank Rate by 0.25 percentage points to 4 per cent at its August meeting – might be helping students’ landlords, but it won’t be impacting student budgets.

Meanwhile, if students have been steadily increasing their term-time work (both in numbers of students and hours worked), that could be a coming problem too. Employment growth has stagnated, and job vacancies have fallen significantly. And while two-thirds of students say they’ve been in work during term time, 89 per cent of applicants are now expecting to find work – rising to 93 per cent of care leavers, 94 per cent of international students and 96 per cent of estranged students.

Either there’s lots of spare jobs going, or the UK may be about to run out of part-time work for students. Almost 100,000 jobs in the hospitality sector have disappeared since the government hiked to employers’ National Insurance Contributions, and the monthly KPMG and REC report on jobs notes a steady and sustained decline in retail jobs too. The biggest sectors for student employment? Hospitality and retail.

A lack of work is a problem few will see coming, will be almost certainly be worse in some cities than in others, and would be exacerbated if the usual ratio of students spending in businesses v those working in those businesses shifts significantly – both having grown gently in tandem as student numbers have grown. The need to convert more jobs on campus to those that students can do has never been greater – even if they sound like the first to have gone as teams have contracted in recent years.

Some will find work that’s further and further away from campus, some will find work that’s more and more punishing on them both mentally and physically, and some simply won’t find it at all. Many – like the international student leader I met last week – will find themselves working for less than minimum wage just to pay their fees, in a country that couldn’t seem less interested in those sorts of labour market abuses if it tried.

God forbid a student has a setback, an accident or a costly health problem. Or happens to be a student in a year when if nothing else, there will be major and un-modelled impacts on student housing supply as a result of dramatic reforms to the way that an already scandalously poor rental market is regulated.

Implosions v explosions

Maybe a crisis is coming – the classic unplanned-for crisis of the sort in The Day Britain Stopped, when various factors conspire in a single period to multiply each other into something that few saw coming. But even if it isn’t an explosion and we see non-continuation rates fall off a cliff, we can see what’s coming – students choosing to stay at home just as their local university closes courses, students choosing against the extracurriculars that would make up for the skills their course supplies but are no longer needed.

Students breathing in the spores of black mould as they literally choose between heating, and eating.

In the 2024 MIS report, the authors warned against any increases to maintenance support that would come at the cost of lower participation in higher education, “for example if an increase could only be paid for by capping the number of students who can study in higher education”. The kneejerk makes sense – neither governments, universities nor students are ever keen on measures that might limit opportunity.

But offering students a loan that only covers half of their basic living costs, and then asking them to work a minimum 20 hours a week during term-time isn’t “opportunity”, it’s a scam – one that sells “student life” but for those on low incomes offers the kind of experience associated with labour market outcomes they’re less likely to achieve anyway, and one that allows lots of people to pat themselves on the participation back while plunging unsuspecting students into poverty.

If the country really can’t afford mass participation in higher education, and students can’t afford to be students, the only morally right thing to do is admit it. And if telling students they need £21,126 per year to live on might put some of them off, then maybe it should.

Thanx for this.

I understand it is not the main point, but I was intrigued that a university believed that there would be enough places for work experience to make it compulsory for all (undergraduate) students.

Indeed, especially if they expected that work experience to meaningfully represent 30 ECTS credits worth of higher education level learning.

The solution is incredibly simple. Cut the number of students in half to around 25% of the population or less. The current system is producing around 200k students a year who are not benefiting at all in career pay terms, and are just left with the life long debt. And even the ones that do have increased pay, there is no actual proof that it is the actual 3 extra years of study that is the causation factor -rather the degree is used as a ‘ticket of entry’ to a higher paid career and can have little intrinsic value. Make… Read more »

There’s no advanced economy that is cutting HE. The enrollment rate in China is 60%. In the UK it is 36%. The debt imposed on students is a political choice. It is not a law of nature.

The government is not a household. It doesn’t need to borrow money in order to spend and it cannot have a black hole in its accounts since it can never run out of money

Worth noting that the amount of debt incurred by graduates in 2025 is close to the level of those coming out 10 years ago in 2015 under the new £9K fees- around £50k and closer to £60k if you qualify for the full maintenance loan over 3 years. This brings home how the household income thresholds and maintenance loan levels have not really changed in 13 years since the fees went up in 2012 – but rents, living costs and wages have increased far more. No wonder more students are living locally and commuting – it’s just cheaper – and… Read more »