There’s been an inevitable focus recently on the earnings threshold over which a graduate from England might have to start paying back their student loans.

There’s been less focus on how much the student might be entitled to in maintenance support in the first place.

We’ve looked before on the site at the way in which the government thinks about households on low incomes (it spectacularly and presumably deliberately avoids even thinking about students), the squeeze that is coming this year for those on low incomes (predictions are now worse than when that piece was published) and the maximum amount that students are entitled to (the way in which it tracks inflation may not actually track students’ real growth in costs).

But there’s another important factor in all that – what student finance professionals know as the “taper”. Because depending on how much income your family earns, you get less than the notional maximum to fund your costs as a student.

And still there never seems to be a single penny left for me

One of the big bugbears of Martin “Money Saving Expert” Lewis when it comes to England’s student finance system is what we used to call the “parental contribution” – the difference between that notional maximum and what a student is actually entitled to.

His basic beef is that where the Department for Education (DfE) and Student Finance England/Student Loans Company used to make explicit the amount that families were expected to pitch in, we now tend to obscure the numbers.

For me that’s always missed the point a bit – mainly because these days even if parents contribute that full amount, it still isn’t enough to cover most students’ costs. That’s a problem we have little proper intel on given DfE hasn’t recommissioned its Student Income and Expenditure survey since it last did so eight years ago. It also makes Lewis’ theoretical victory before Christmas – where he appeared to get a commitment out of Michelle Donelan that the number would be clear in the future – somewhat pyrrhic.

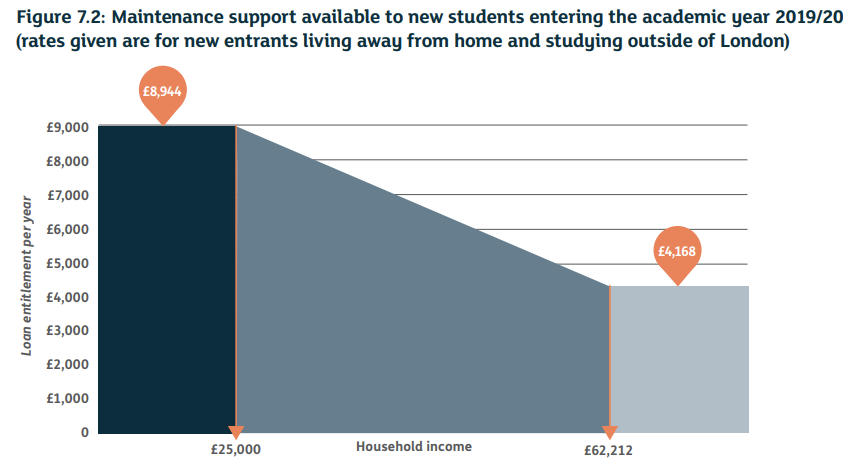

But let’s focus back on that taper. To help get your head around it, here’s the illustration of how it works that was in the Augar review back in May 2019:

Augar didn’t say much about the taper – most of his panel’s material was instead focussed on the max and sensible ways to peg that max, which we’ve discussed on the site before.

I wouldn’t have to work at all, I’d fool around and have a ball

But the taper matters. In principle, that graph above is defining a low income family as one on £25,000 or less. And in practice the threshold over which parents are expected to chip in some cash – and therefore the maximum loan starts to be reduced – hits some of our poorer students in the pocket hard.

We could go back a long way on the means testing thing (and what has counted as household/parental income), but for now let’s just look at the system and thresholds introduced when £9k fees appeared.

The mixed system of grant and loan that applied in the first half of the past decade was actually preposterously complicated (see section 4.3 here), but the TL;DR is that in September 2012, you started to get less than the max – with parents having to start to chip in – at £25,000.

The problem is that 2012 was now, literally, almost a decade ago.

There’s lots of different ways to look at what has happened to that 25k figure over the decade – we could look at changes in growth in wages, inflation (both CPI and RPI), changes in average household incomes, the volume of families now caught by the taper or the Department for Work and Pensions’ “Households below average income” dataset.

But for absolute simplicity, let’s just use inflation.

For the 2012/13 academic year, the household income used to determine the rate was based on the 2010/11 tax year, and for the 2022/23 academic year, the household income that will be used to determine the rate will be based on the 2020/21 tax year.

Back in 2012 the government decided that students whose families earned under £25,000 in 2010 needed the full help. In 2020 money (using CPI inflation) that figure would be almost £8k more – £32,653.

But Donelan has already announced that it will still be pegged at £25,000, a full decade on.

That means that the £25k family income we decided needed full help in 2012 would now, in equivalent terms, be subject to a taper that deducts the following amounts from students’ entitlements:

- Away from home, outside London: -£1,039 (11% of £9,706)

- Away from home, in London: -£1,057 (8% of £12,667)

- At home with parents: -£1,030 (13% of £8,171)

This is, put simply, a scandal – especially when it looks like costs (esp housing) have risen faster than both inflation, and the maximum entitlements over the decade.

It’s not a scandal that’s confined to the government either. I’ve been looking at various universities’ access agreements/access and participation plans and I see the same problem popping up locally too. Maybe it was forgivable for a large part of the last decade when inflation was so low. Those days are gone now.

In my dreams I have a plan

Now of course it is the case that the very poorest still get full support. But by lazily letting the definitions slip, both the government and universities do that thing that people keep claiming the student finance system prevents – they price talented students out of the system, while telling the world that poor families still get full help.

That Augar and his panel were commissioned to address disadvantaged students’ maintenance support yet completely failed to address the family income taper was bad enough. That it could be about to be unresolved in the formal response to Augar – and not really noticed by the press or politicians – would be obscene.

Again for those at the back. Converting some of the loan into grant (as Augar proposed) without changing the cash in hand entitlements – insofar as it would give confidence to some that they can afford something that in reality they can’t – would be a nasty scam.

Remember that it’s the government that constantly allocates responsibility for non-continuation to universities, we don’t actually ever systematically collect the reason(s) for dropping out when we could and should, and OfS doesn’t even tell us the value of additional financial support going in from universities per “£25k and under family income” student any more (what we used to call “OFFA countables”).

And before anyone starts to argue to me that if this was a real issue we’d have seen huge numbers of low income students dropping out. There’s a dangerous strain of political thinking that pegs acceptable minimum incomes to live on with higher education participation rates and drop out figures.

Hear this. Contrary to the “low aspiration” trope, students on low incomes will attempt to live on gravel to do the right thing and pursue their ambitions, dreams or careers of service.

That doesn’t mean that it’s right – and the resultant better performance of their better-off peers both in attainment and in the labour market almost certainly has a lot to do with the extra-curricular opportunities they can take advantage of, while their low income counterparts work full time to (sometimes fail to) make ends meet.

Some time since I delved into Wonkhe articles. But this blunt and accurate assessment reminds me how disingenuous Govts are and how these built-in structural disadvantages hit the lower paid again and again. And in the comfortable HE sector, a bastion of middle class patronage and representation.

Not sure I wanted the reminder – but many thanks all the same!