This year signals UK higher education’s very own anthropocene – a sector-defining point at which universities pivoted en masse to deliver emergency online teaching and new modes of working.

It will leave a permanent trace of the seismic change in practice that has been undertaken in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. A period where academics spent several hours recording one-hour lectures via technology platforms such as Kaltura, Panopto, and the failsafe humble workhorse PowerPoint. A period where meetings were organised through corporate platforms that presented opportunities for a new type of tyranny.

The digitalised world

The technology sector refers to such types of transformation as “digitalisation” – where an overhaul of operating models, new recruitment processes, new ways of integrating information and digitally based business models are used to produce more valuable products, services and new markets. In business environments, some of the drivers for digitalisation have included: mobility, big data, artificial intelligence, social media usage and cloud-based services. Such drivers are also relevant to higher education

In an academic setting this brave new future, while beguiling in its promise, requires a more sensitive treatment. We need to be clear about what digitalisation might mean for the higher education sector – positive and negative.

While it is clear that the current situation and the move to online is an emergency response from universities, the “new normal” requires the rethinking of existing practices and a plan for change adding resilience to operating models. I propose that digitalisation may be an appropriate framing device to both understand this current emergency response and one that is sustainable into the future.

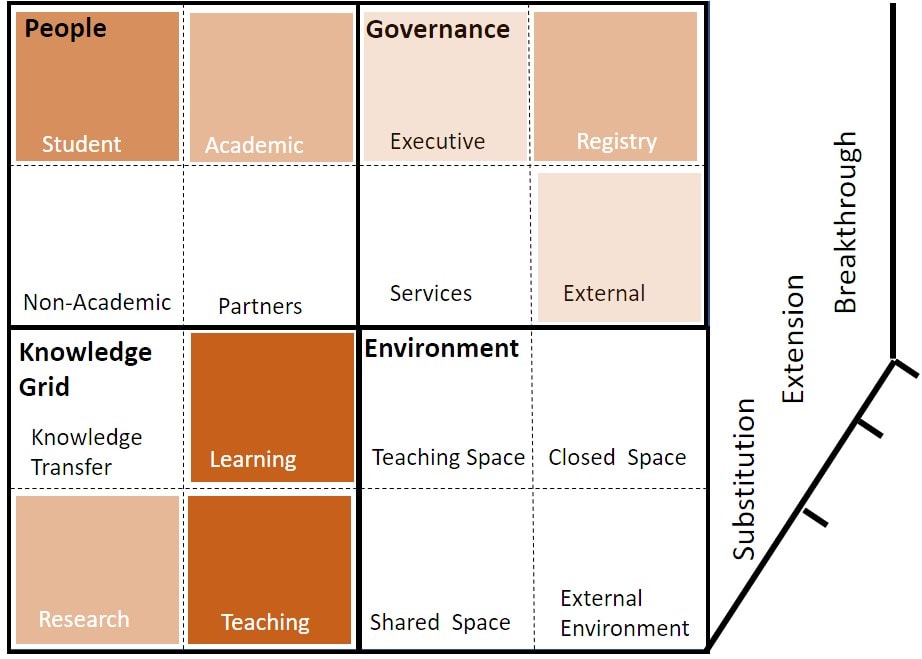

Figure 1 Digitalisation across University Quadrants

How has digitalisation been enacted in the current situation? Evidence is emerging that changes are visible in several quadrants of the university enterprise (see figure 1). Most notably, students, academics, and learning and teaching have received immediate attention through the switch to online teaching modes. Research in non-lab and non-field settings remains largely intact except where travel and spend is being impacted. Lab-based research and fieldwork is on pause, and while there are strategies to conduct field work through social networking sites and the use of proxy data, the move to digitalisation has not taken hold. Critical lab-based scientific research continues in many universities, albeit on a reduced footing. Services supporting governance have moved to online meetings conducted through video-conferencing technologies. As universities conclude the term’s teaching, assessments have also gone through a digitalisation filter and moved online or to offline time-based modes. The next challenge facing those tasked with governance structures of universities, is how to manage assessment boards so that the required quality assurance can be maintained.

Online, but not ubiquitously

Many key processes have been put on hold and present new opportunities for digitalisation. For example, new programmes and courses and their associated validation processes require a re-think. PhD examination vivas can now be held as online meetings, but there remains uncertainty as to whether right-to-work checks for external examiners will remain in place, and how such verification might be obtained digitally. The environment is now, most definitely, remote and online.

Intersecting across these quadrants are questions around how anticipation or planning for digitalisation can be executed. For the purposes of debate and critique it is proposed that a staged approach that can be used to plan change for these quadrants. Three stages are identified:

- Substitution – where one mode is replaced with another;

- Extension – where existing practice is enhanced with new modal affordances; and

- Breakthrough – where practice undergoes a radical change.

In this current pandemic situation, the universities’ digitalisation change is typically one of substitution. We are finding alternative ways of doing the same work. Thus, a lecture given with PowerPoint slides in a classroom setting is substituted with a lecture and voiceover delivered over Moodle or some other e-learning platform. A future extension might be to ensure that all courses validated in the future have a 25 per cent built-in distance learning mode to create a future resilience, be it for the next pandemic, reducing pressure on teaching spaces, or even the illness of an academic. New modalities could include technologies for replacing lab-based experiments with simulation. What would a breakthrough advance look like? That remains a futures project.

Similarly, springtime usually sees the arrival of future students attending open days. Universities are being creative and open days have now moved online with virtual tours and online drop-in sessions with academics, and perhaps offer new and more innovative modalities. The success of this substitution will become apparent later this year.

Many digitalisation opportunities reside within these quadrants. Communications beyond the usual broadcast mail can be utilised. MS Teams on the mobile device provides a ready-made academic social network for an organisation. Once the pandemic is over, the physical spaces of a university campus can be re-imagined with widespread use of embedded devices, and improved analytics which will enable universities to better utilise physical resources. Some experiments are already underway using presence sensors to record class attendance.

Digital twins

With the widespread availability of near real-time data, analytics and machine learning techniques, the notion of a digital twin can make innovative forays into the HE sector as a key decision making aid for the future. A digital twin, simply put, is a realistic digital representation of a real-world entity, asset, process or system. Planning departments could be revolutionised through improved decision-making capabilities delivered through digital twin technology.

This move en masse to online delivery has the potential to reposition the role of the university in the community. As citizens are in lock-down, here is an opportunity to deploy technology enabled learning at scale, and allow universities to play an enhanced role in the education of citizens – a truly widening participation agenda. Further, in line with the industry-academic partnership model, courses can be re-configured as new programmes for continuous professional development. Universities have always worked in the national interest, but the current pandemic has shown how universities are playing their role, for example, through the manufacture and supply of face visors for NHS workers.

Digitalisation also offers new data at a granularity and sensitivity that traditional university planning cannot easily replicate. For example, some online platforms for video-conferencing such as Zoom provide data on when the virtual meeting attendee is doing other things on their computing device. This leads to new challenges that need to be also considered when embarking on a digitalisation journey.

Opportunities for increased monitoring of work productivity arising from access to new forms of data through data synthesis and continuous measurement (e.g. the status indicator on MS Teams) may prevail. Higher education, in its response to this pandemic, could create new forms of technocratic governmentality through the availability of a technology-led instrumented rationality. What can be measured, will be. What new governance needs will arise?

As digitalisation takes hold, large technology companies on which universities increasingly rely upon, seemingly uncritically, will be in a position to colonise data generated in public environments with a view to monetisation of that data. Or, at the very least, to lock universities into platforms making future change prohibitive.

Until this year, studying the university as a digital enterprise was essentially a futures project. The current Covid-19 pandemic has created wide-ranging disruption, and the moves undertaken to combat this disruption are a testament to the adaptability and resilience of the sector. In responding to this emergency situation, modes of operation have changed. The question will be how to move from beyond substitution to the extension and breakthrough stages of digitalisation while addressing some of the concerns raised here. Is digitalisation the best framing device? The debate is open.

Balbir many thanks for your thoughtful article – liked the grid – we are a partner of MU delivering an apprenticeship BSc and an MSc programme – we have digitalised all our curriculum and in doing so created new opportunities . We have all had to get smarter fast in using digital tools such as Zoom , breakout rooms , polling and using student support time in a. different way I am interested to learn more of how MU is responding to the new normal ..

[…] “This year signals UK higher education’s very own anthropocene – a sector-defining point at which universities pivoted en masse to deliver emergency online teaching and new modes of working.” read more […]