In Wednesday’s joint Spending Review and Autumn Statement, the government confirmed that it will be freezing the loan repayment threshold for all student borrowers who have started since 2012.

Rather than being increased in line with earnings, the threshold will remain at 2016’s level of £21,000 until April 2021, when the threshold will be reviewed again. This represents a change of terms which will see lower to middle graduate earners repaying an additional £6,000 in net present value terms over the lifetime of their loan.

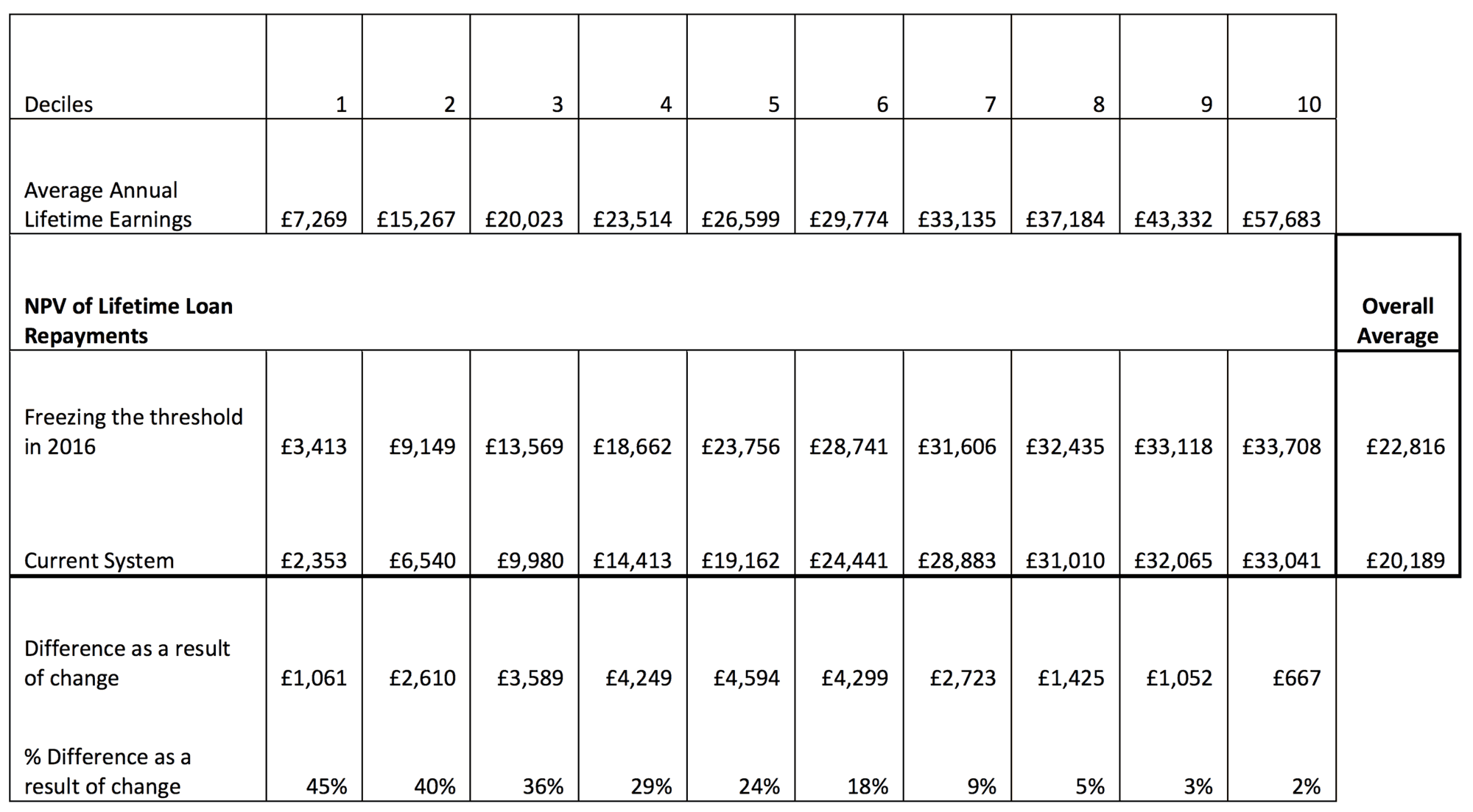

Freezing the Student Loan Repayment Threshold: Equality Analysis, p. 38

In cash terms, the government is keen to emphasise that this will be about £6 per week or an additional £300 per year from 2021 until the loan balance is cleared or the accounts are written off 30 years after repayments first fall due.

I share many of the complaints about the unfairness of what are effectively retrospective price hikes introduced after borrowers have signed up and even graduated. The sums raised have probably allowed for the age restrictions on the proposed postgraduate loans to be lifted, but that will be a quid pro quo for the sector that doesn’t benefit the individuals affected by the new loan terms.

The justification offered is that this freeze brings the threshold in line with what was envisaged in 2010:

When the £21,000 threshold was set by the previous government in 2010, graduate earnings were expected to grow more quickly than they have done. The threshold would now be set at around £19,000 if it were to reflect the same ratio of average earnings. (Consultation Response, §103)

The economy has performed much worse than expected and so the threshold is higher relative to average earnings today. The government could have corrected this perceived problem today by committing to an appropriate ratio and fixing the repayment threshold in relation to it. Indeed this would have turned the freeze into a one-off recalibration.

Instead we have something more troubling. The government largely ignored submissions to consultations and chose not to adopt various ways to mitigate the proposed options. It rejected any suggestion that it might fix terms and conditions for borrowers from now on with a one sentence dismissal:

Fixing loan terms and conditions would give more certainty to borrowers, but would reduce the Government’s flexibility to manage the loan book in the future. (§117)

In the first instance, managing the loan book will involve reviewing the threshold again in 2021. There is no commitment to restoring a link to changes in average earnings. Although the modelling of the impact on repayment has been conducted on that basis.

But more generally, a student finance system dependent on such large levels of graduating debt needs to give as much confidence as borrowers as possible. For students, income contingent repayment loans are unfamiliar and it is fundamentally difficult to assess your likely contributions over 35 years. The government is now signalling that it is rational to reduce graduates’ exposure to starting debt, and thus make it less likely that one will be caught on the wrong end of a further future review reviews that tighten repayment conditions.

Those most likely to be affected by repeated reviews are the same lower and middle earners most affected by this change.

I would be interested to see what the Competition and Markets Authority and Which? make of this development. They have so far concentrated on the advertising practices of universities, but the headline tuition fee is not a price – what price a student pays is determined by repayments they make as graduates.

Students also graduate with other debts (overdrafts, bank loans, credit cards, payday loans, etc) and these have more onerous repayment conditions early on. But the government appears to have no robust method for determining what impact its changes will have on graduate disposable incomes. This point is more critical for the proposed postgraduate loans where the government has insisted on concurrent loan repayment. Even if the postgraduate repayment rate is 6 per cent over the £21,000 repayment threshold, rather than 9, the two combined (undergraduate and postgraduate) means that the government will have a marginal take of 47% from those with both kinds of loan: 20% income tax, 12% national insurance, plus 15% student loan contribution. For those on the next tax band, that marginal take increases to 67% of someone’s income over £42,385.

What would a rational response to this change be as a potential student? By lowering graduating debt, one will lower exposure to the vagaries of policy-contingent loans. This means it becomes rational to avoid studying away from home in London or for longer full-time programmes.

Before that change was made, additional debt might have simply represented more write-off for government – now that it is not the case.

If you could avoid coming from a poorer household that would also help. Too few in the HE sector have attended to how the repayment threshold freeze combines with the abolition of maintenance grants for new starters from 2016/17. 45 per cent of students who have started since 2012 have received a full maintenance grant – roughly 425,000 individuals annually. Another 140,000 received a partial maintenance grant.

People are familiar with the conclusion that those coming from poorer backgrounds will now face higher graduating debts as a result of these changes. But the resulting costs are determined by repayment terms.

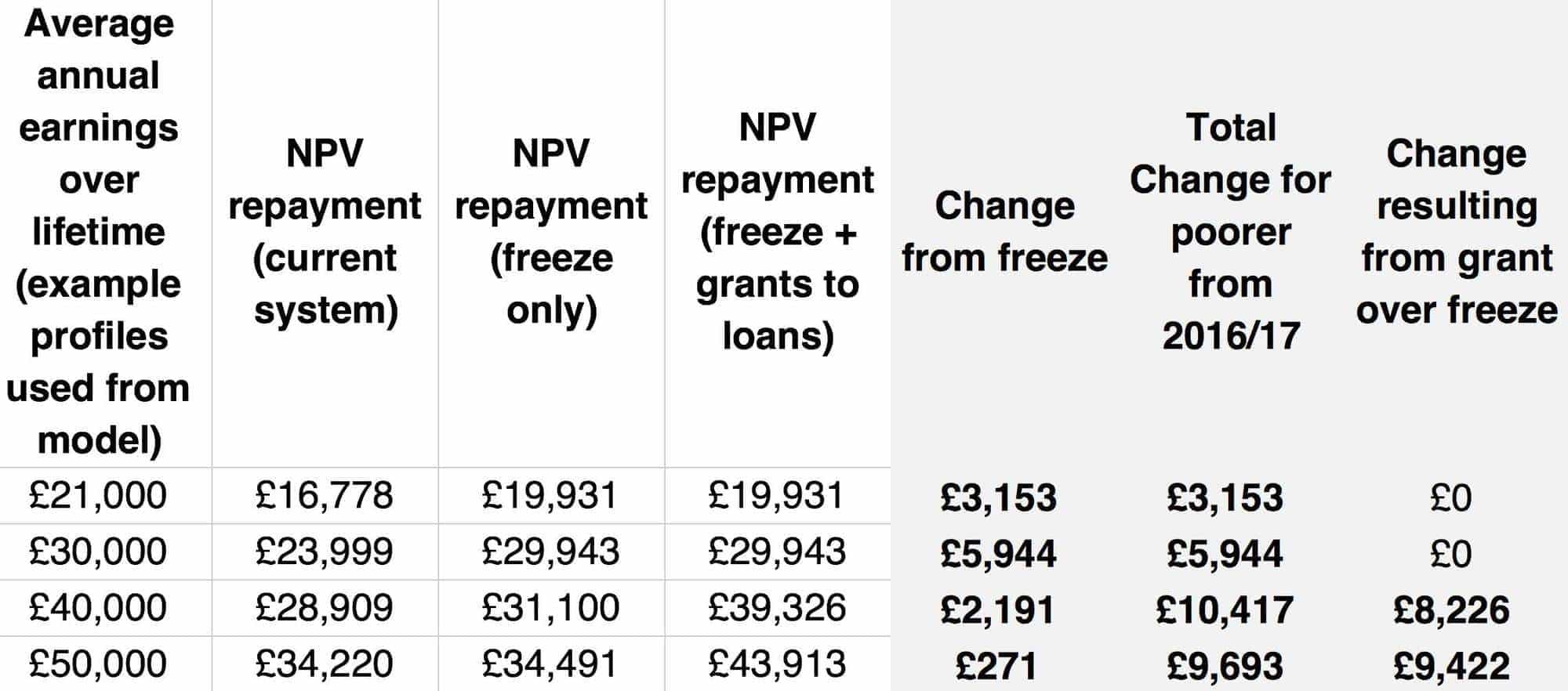

In the government’s 94-page Equality Analysis assessing the proposed freeze (published yesterday), figures show that without the freeze, lower to middle earners would see little change from higher graduating debts. But when you look at socially mobile individuals, the situation changes. Those who start from poorer backgrounds who become higher earners pay a premium compared to those who come from better off families.

The table below is adapted from figures provided by BIS’s Equality Analysis. It shows that the freeze is more significant for lower and middle earners, but that graduating debt combines with the freeze to create a tax on social mobility. The two examples of higher earner individuals repay more than £8,000 than their peers who started with lower graduating debt.

All figures above are in Net Present Value terms produced using the government discount rate of RPI plus 2.2%. The government has now announced a new much lower discount rate, but from the graduate perspective an appropriate discount rate would be RPI plus 2% (long run average earnings) so these are a good indicator for the individual. Rerunning these calculations with a lower discount rate would push all the values up.

In effect, we have produced a higher education system with a new form of inequality – the price of education for higher earners is different depending on what background you have. I do not see how anyone can endorse this. This BIS analysis tallies with that produced independently by the Institute for Fiscal Studies in July:

We estimate that 65% of students who would have been entitled to a full maintenance grant are likely to experience no change in how much they can expect to repay (as they would not have paid back their old lower loan in full, let alone their new higher loan). Of the remaining 35% of those students, the average student will be repaying their loan for an extra four years, contributing an extra £9,000 towards their degree. IFS quoted here.

But BIS’s Equality Analysis concludes that these figures will not affect participation in HE and so are unproblematic:

Under a grants to loan switch, those affected will experience an increased level of debt and this may create an additional risk to participation. However, in terms of lifetime repayments, it will only be those that go on to experience above average lifetime earnings that will be affected. Such individuals’ are those most likely to have benefited from attending Higher Education. Where individuals are able to understand this, it is likely this will offset any greater risk to participation. Overall, we believe while the risks are increased, they remain low. Equality Analysis, p. 68 (my emphasis)

I don’t believe the government has intended to create a tax on social mobility but it is now ignoring its own evidence that it has done so. Fundamentally, a student finance system must be fair and be seen to be so. It is not enough when assessing changes to finances, simply to test whether individuals will understand the consequences or be deterred from participating. We can’t have price differences in the system that are based on family background.

The English HE sector is probably sighing with relief that their incomes won’t be too badly affected by yesterday’s announcement. But it has a more fundamental issue to deal with – its sustainability depends on good will and a well-functioning student support system. That system needs to be fair, progressive, affordable for graduates and adequate to costs of student life. It is not clear now that our current system will still meet any of those requirements by 2020.

What is the value of this reassurance from BIS, “in terms of lifetime repayments, it will only be those that go on to experience above average lifetime earnings that will be affected”? (Equality Analysis, p. 68)

It is worthless. They have now established the precedent of retrospective changes, and they have a get out clause that enables them to change any of the loan terms, so who can say what those borrowers on low earnings will have to repay over the next three decades or more.

I completely agree John. Regardless of whether changes are rightfully made and proven to be the correct decision, retrospective changes are completely unjust. Who’s to say they can’t change the rules in the future and you never stop paying back your loan, even once you’re drawing your pension? If the banks changed loan conditions after taking the loan there would be all sorts of problems so why is it so easy for the government to get away with? Overall in the long term these retrospective changes will deter prospective students on the grounds that what they may think is an… Read more »