Some seem to think that management numbers are growing too fast

HESA, the Higher Education Statistics Agency has recently published its annual summary of staff numbers in higher education. The headline data follows:

Academic staff

Of the 181,185 academic staff employed at UK HEIs, 44.2% were female, 12.4% were from an ethnic minority and nearly a quarter (24.8%) were of non-UK nationality.

17,465 academic staff had contracts conferring the title of ‘Professor’. Of these 19.8% were female, 7.3% were from an ethnic minority and 16.7% were of non-UK nationality.

Non-academic staff

As well as academic staff, there were a further 200,605 non-academic staff employed at HEIs in 2010/11. The majority (62.4%) of these staff were female. 10.0% of non-academic staff were from an ethnic minority and 9.3% were of non-UK nationality.

16,395 non-academic staff were coded as ‘Managers’. Of these 52.4% were female, 6.0% were from an ethnic minority and 5.9% were of non-UK nationality.

This is the definition of ‘Managers’ used by HESA:

Non-academic Managers are defined as those individuals who are responsible for the planning, direction and co-ordination of the policies and activities of enterprises or organisations, or their internal departments or sections. Senior academics who act as vice chancellors or directors/heads of schools, colleges, academic departments or research centres are coded as academic staff.

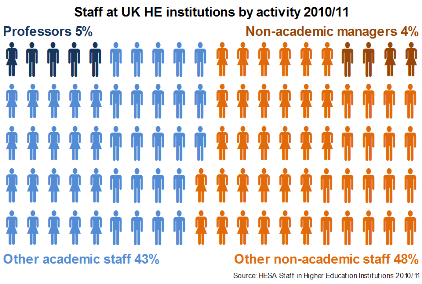

To summarise this HESA offers a handy infographic:

On the face of it this all looks pretty innocuous but it seems that, despite the relatively small number of managers in the sector, around 4% of the staff total and smaller than the professoriate, the rate of growth of managers has been faster than academics. For some, according to the Times Higher Education, (which seems to use different data in places) this is a bit of a problem:

The percentage increase in the number of managers in higher education in recent years is more than twice that for academics, an analysis of new figures has suggested.

Data released by the Higher Education Statistics Agency reveal there were 15,795 managers in higher education in December 2010 – up by almost 40 per cent on the 11,305 employed in the 2003-04 academic year.

That was compared to the 19.2 per cent increase in academics since 2003-04. It means there is now a manager for every 9.2 academics compared with a ratio of one to 10.8 seven years earlier.

Sally Hunt, University and College Union general secretary, said: “Despite the fact that there has been a large increase in the number of students in recent years, there has been a larger increase in the number of managers than academics.

“We have raised fears about the changing nature of universities as the market in higher education continues to grow. However, institutions and government must never lose sight of universities’ key roles in teaching and challenging students.”

Meanwhile, statistics released by Hesa on 1 March showed staffing levels at universities fell by 1.5 per cent last year.

The figures showed there were 381,790 people working at UK higher education institutions in 2010-11, down by 5,640 from 2009-10.

These numbers though really are not large and manager numbers have grown by just under 4,500 at a time when academic numbers have grown by over 16,000 (which makes the point from Sally Hunt factually incorrect).

The UCU comment suggests it is taking its lead from David Willetts. He made a similar point in a speech made to a UUK conference back on 9 September 2010:

There are other ways of cutting overhead costs. In 2009 the number of senior university managers rose by 6% to 14,250, while the number of university professors fell by 4% to 15,530. On that trend the number of senior managers could have overtaken the number of professors this year. I recognise that universities now are big, complex institutions with revenues from many sources which need to be professionally managed. But we owe it to the taxpayer and the student to hold down these costs – we are now in a different and much more austere world. Again, we are not going to shirk our share of responsibility for tackling this. We will to do away with unnecessary burdens upon you that require the recruitment of more administrators. Do tell me – and HEFCE, of course – of any information requirement or regulation which you believe comes at a disproportionate cost. They have to go: we cannot afford them.

So this is the moment to be thinking even more creatively about cost cutting. I congratulate you on your initiative in inviting Ian Diamond to chair a UUK group on efficiency savings. You are right to get to grips with this. We can work with you on this agenda without getting sucked in to micromanaging our universities. No returning to a time – a century ago, actually – when one vice chancellor reacted to a Board of Education demand for figures on staff teaching hours by complaining that “Nothing so ungentlemanly has been done by the Government since they actually insisted on knowing what time Foreign Office clerks arrive at Whitehall.”

As noted in a recent post, these claims about reducing regulation ring rather hollow and, given that government demands on universities have increased rather than declined, this does perhaps provide one explanation for the growth.

How signifiicant is all this though? While the staff group ‘managers’ has grown faster than academic professionals at all universities and at Russell Group universities (but not at Nottingham as it happens), this is a small category of staff representing only 7-8% of all non-academic staff. The definitions of the various staff groups provided by HESA do allow some judgement in the allocation of staff to the various groups and there is some evidence of differing practice at different institutions. However, the definition of academic professional is straightforward and unambiguous and it is clear that at Nottingham such staff have grown considerably more than non-academic staff since 2003-04.

Universities need managers to function effectively. They are key to enabling academic staff focus on delivering excellent research and first class teaching and for protecting academics from the worst regulatory excesses of government. So this modest growth is really nothing to get excited about.