Unless students and their reps are doing it, I generally despair at the habit of framing higher education policy deliberation through the optic of “when I was a student”.

But sometimes it’s personal.

I was a first in family and all that. We’d read up on the costs of university from a booklet from the library, and I saved up in my year out.

Inevitably, it wasn’t really enough. My parents helped and I got maintenance, but it wasn’t enough.

It’s hard to communicate clearly what that feels like. It’s not “silly Jim overspent when his grant came in,” it was “Oh God. Maybe I can’t actually do this.”

You basically panic. You can’t go for a coffee with everyone else. You can’t go out on Friday with your tentative new friends. You are going to have to try and scrounge to afford anything on the field trip. And so on.

But you know you can’t leave. You’d be letting everyone down.

At first I had a job in a shoe shop in Bath (I was at UWE) but that effectively isolated me while I wasn’t studying.

I was enormously, incredibly lucky – by chance I blagged a job in the SU bar on campus that enabled me to build a social community while I was at work. Not everyone gets those chances.

Help me out of the life I lead

Does this problem on estimating costs persist today? In 2011, Public First polling for the All-Party Parliamentary University Group asked prospective students about day-to-day living costs at university.

One in five that were to be be “first in the family” figured they would end up spending less than £100 a week – a figure that halved for those whose parents had been to university.

Research has repeatedly told us that not only do students and their families underestimate the costs of higher education, the less experience friends and family have of it, the bigger that underestimation.

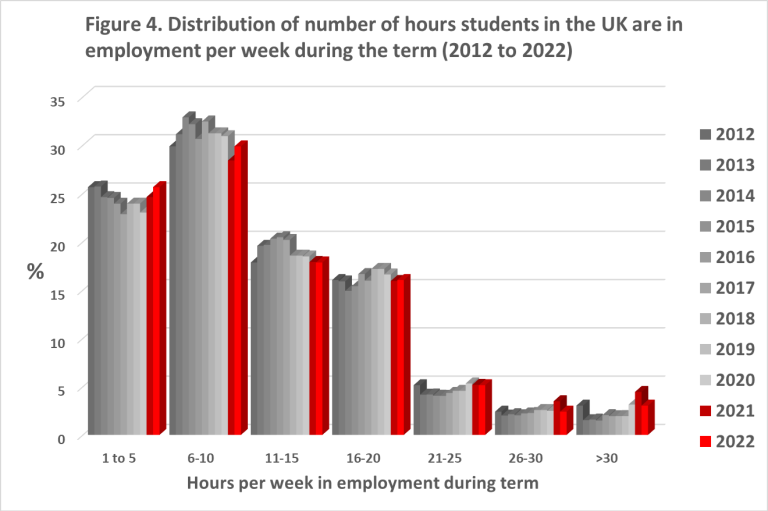

That was less of a problem in an era where a bit of part-time work could be found to make up the difference. But when getting on for a quarter of students who work are now working over 15 hours a week in term time, their inability to close that gap is growing:

(Source: HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey, on Total Equality for Students)

So this time last year I thought I’d have a look at what universities were saying about the costs of participation in higher education.

I thought the information on offer, generally, to be breathtakingly inadequate – poorly sourced, rarely updated and almost universally “fingers in years” about the rocketing rate of inflation we’d already seen that calendar year.

At the time, I urged every university in the UK to review the information they were putting out to address the dangers of convincing students that they can afford higher education when they can’t.

A year on, I’ve taken a fresh look. The good news is that in some cases, the information has dramatically improved. But in some many other cases, the information has either not improved, or has gotten significantly worse.

As ever, full disclosure on method – I searched for the terms “cost of living” or “living costs” with the filter site:ac.uk between 26th June and 30th June 2023. Where I found some cost of living of advice, I looked for any source for the figures, and used archive.org to see if the advice has changed any time recently.

I’ve also resolved not to name and shame this year – lest it lulls everyone else into a false sense of information security.

£200 rents in Scotland’s capital

My search didn’t start well. This time last year, the first page that I chanced upon on was a university webpage telling students about the cost of individual aspects like rent, food and laundry using figures from the Nat West Student Living Index – a “source” that last year laughably suggested that Edinburgh rents had halved to £200 and the year before told students that a pint cost £9.10 in London:

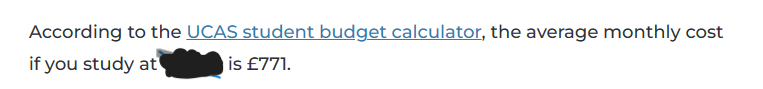

This year that university has gone one better – removing detail on costs altogether and replacing it with an “average monthly cost” for students living in the city that just so happens to be lower than the eleven other universities listed underneath it. Its “£755 a month” figure sounds official – but the reference given is the UCAS/Which Student Budget Calculator, now withdrawn, and whose figures were last updated in…2019.

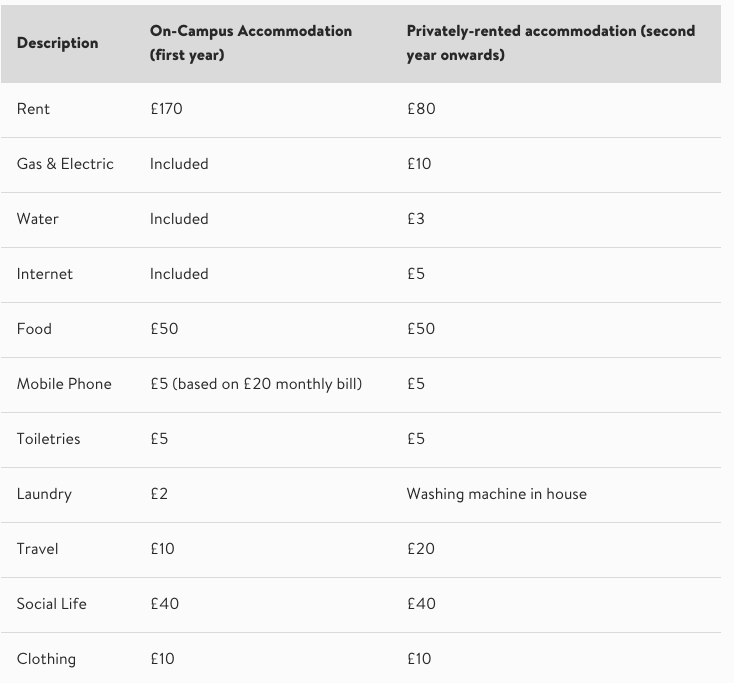

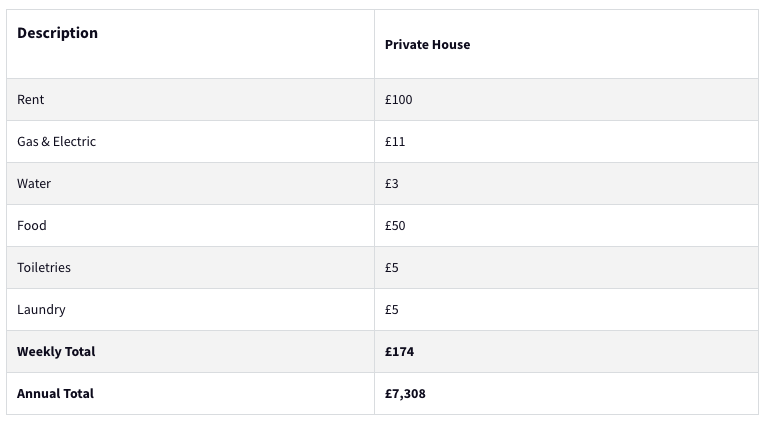

Here’s another typical example:

For some, it’s the calculator that isn’t there. For others, it’s the reliance on the NatWest Student Living Index that is pretty terrifying. One university uses it to boast that its city has “one of the lowest rents in England”. Another takes its national averages when its own city’s figures are significantly higher.

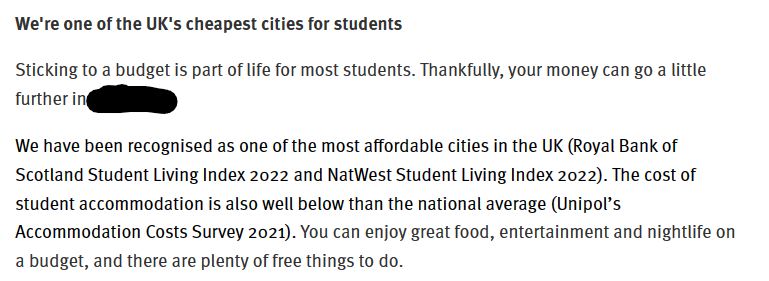

Another says that it is “one of the most affordable cities in the UK, quoting the “Royal Bank of Scotland Student Living Index 2022 and NatWest Student Living Index 2022”. That’s two different logos on the same problematic bit of polling, folks.

Around one in five universities I looked at sensibly attempt to dodge the problem of trying to estimate student costs altogether, and instead just link directly to the Which? Student Budget Calculator, or link to that via the UCAS Budget Calculator (which was in itself a wrapper page for the former).

As I say, the problem is that neither of the links now work – the figures in the Which? source were last updated in 2019, although the javascript driving it is unhelpfully still available on Which? servers, misleading students whose chosen universities embed it in the process.

Inflation? What inflation?

To read many university webpages, you’d think the city they are in has somehow been exempt from the record levels of inflation that the UK has been experiencing. This one is unchanged from a year ago:

Here’s another where the figures haven’t changed since summer 2020:

And here’s one where the numbers haven’t changed on the university site since January 2020:

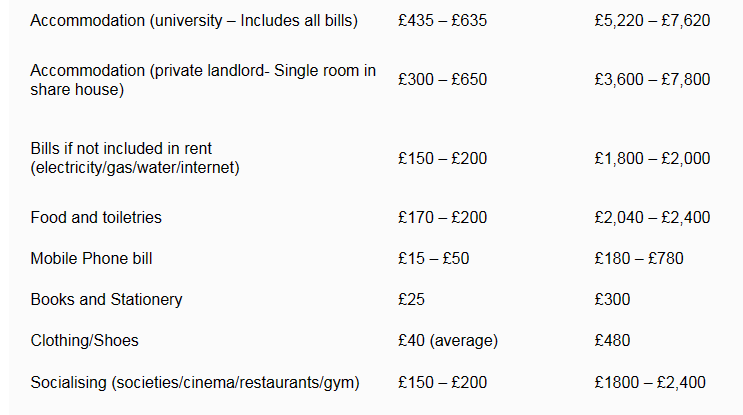

Sometimes figures are updated – but only to reflect the way in which the price of halls have gone up, with everything else remaining oddly static:

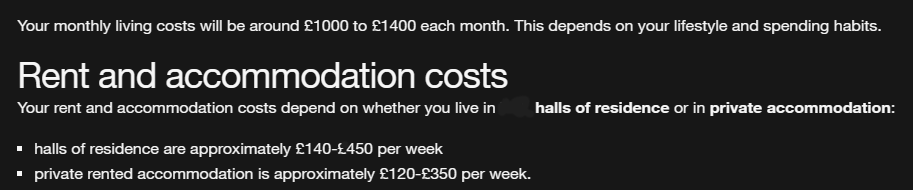

This London university has been telling applicants that their monthly living costs will be around £1000 to £1400 each month since at least March 2021, and while it adds that “this depends on your lifestyle and spending habits”, it doesn’t add “and also depends on if you’re Marty McFly”:

This one hasn’t changed its estimates on living costs since 2018:

Sometimes a single university can’t get its story straight. Here’s an example of one where the university has at least two different (live, current) examples of monthly student costs on different departmental webpages:

Back to the future

Even where universities quote actual sourced figures, there are real dangers in the way they are presented.

One common practice is to quote the year ahead’s university halls rent prices, but for everything else using sources like Save the Student’s national student money survey – which show the year before’s costs.

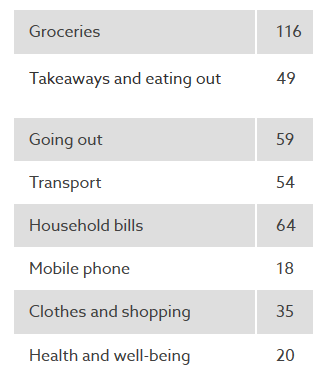

Telling students that they might expect to spend £116 a month on groceries (fieldwork January 2022) without telling them that food inflation has been running at about 20 per cent means that the guesstimate could easily be £1,500 a year short by this September – let alone how wide that gap will grow over the duration of the programme.

And those universities in London using Save the Student figures for expenditure types, while keeping schtum about Save the Student figures on how much more expensive the capital is on average, really are obscuring important realities.

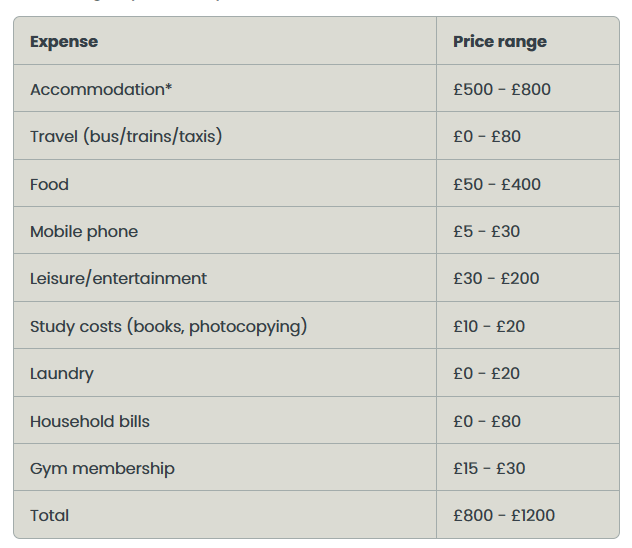

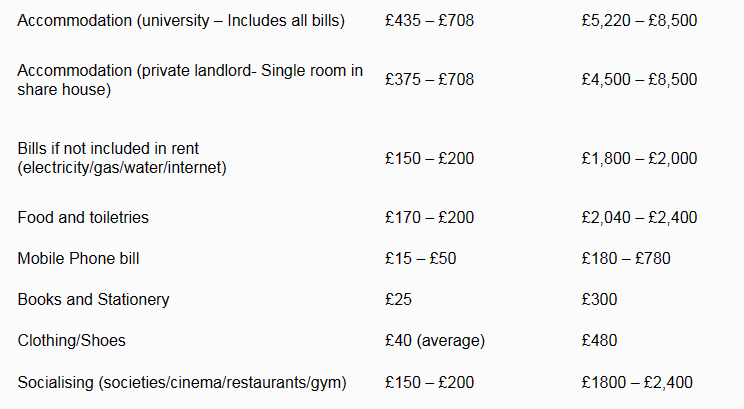

In some cases, as well as not updating the numbers over the past twelve months, at least ranges of costs are offered – but some have a range so large on each cost as to be almost meaningless. Here’s one that hasn’t been updated since 2021:

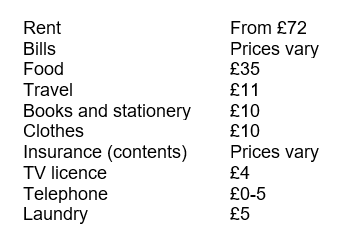

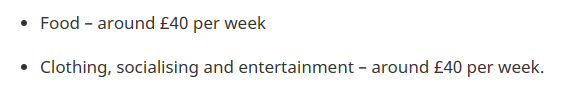

Often the pages will link to a source or at least quote a source – but in a number of cases do neither. Here’s one such university, which has also switched from quoting weekly costs to monthly costs without inflation really kicking in:

Many of them just seem to pluck “average” figures from the air. Here’s an example of an unreferenced set of costs in a video:

And a significant number of international-oriented webpages lazily quote the Home Office’s basic financial requirement as if it’s actually rooted in reality:

Some even just use those figures as if they’ve been researched, rather than just reflecting a limit that the HO hasn’t been bothered to change since at least 2020.

“We estimate” indeed.

Dim chwyddiant yma

For reasons that are not immediately clear, Wales seems to have a particular issue with keeping costs estimates up to date and giving students decent information.

One university boasts that it came first in the 2022 NatWest Student Living Index, which it says “accounts for factors such as how much students spend on going out to income through part-time work”. Sadly it doesn’t account for woefully low sample sizes and frequently preposterous results.

Another university is also keen to tell prospective international students that it is ranked “first in the UK for lowest cost of living for students”. The source for that claim is a TotallyMoney league table from 2019, whose laughable methodology I’ll leave you to critique in your own time. Another quotes an ABC Finance Survey from 2021 (with a similarly laughable methodology) to claim that it’s the third cheapest student town in the UK.

One says its figures for 2023 come from the Save the Student student living costs survey (published September 2022) and quotes UK averages – ignoring the trouble that StS went to to calculate costs for that university’s city. Another quotes mysteriously round and unsourced figures for average UK costs of things (“Takeaway coffee – £2.50”).

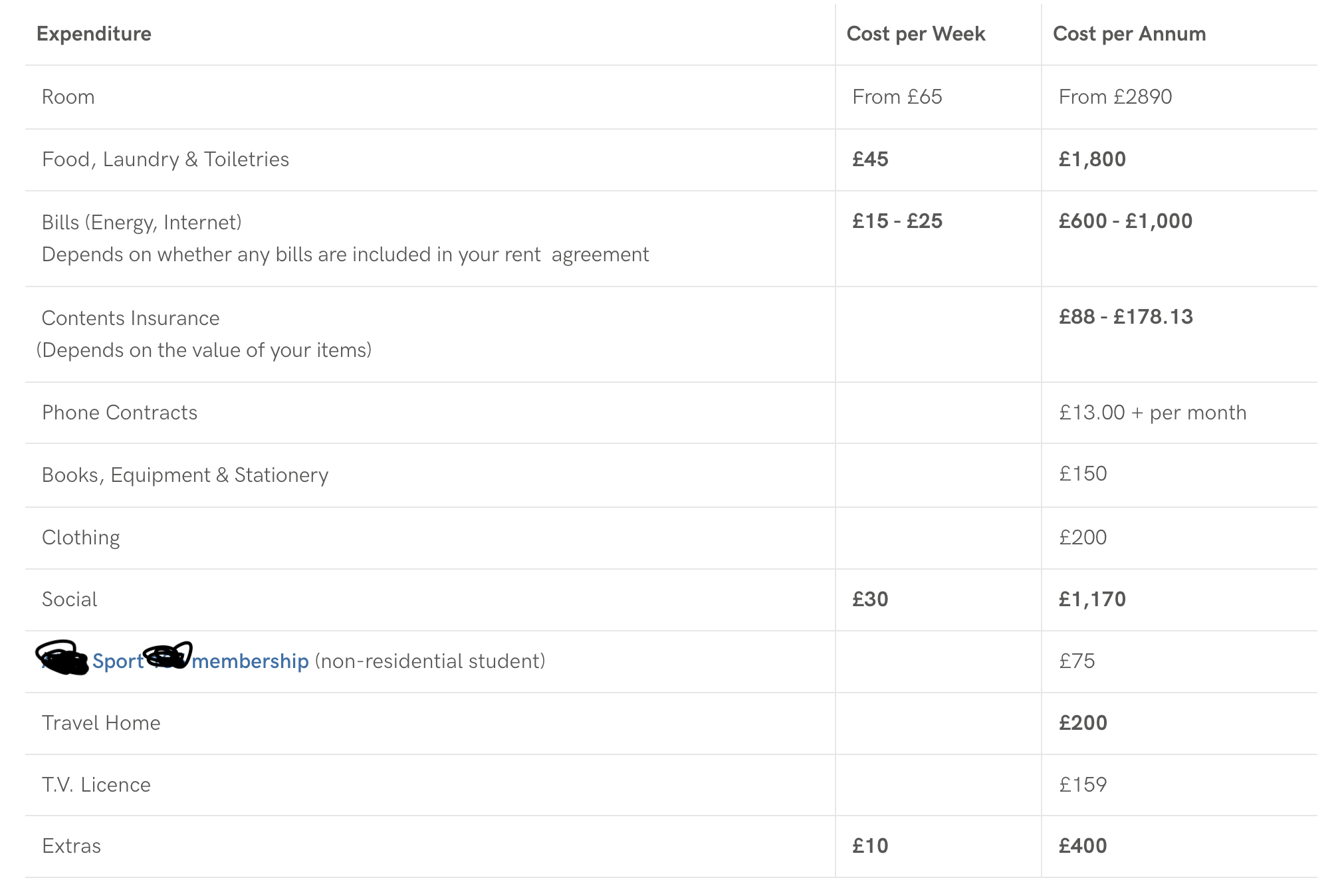

My award for the worst example I’ve seen this year goes to another university in Wales that has found the time to update prospective students on the cost of its own halls and sports facilities and the TV license, but hasn’t updated anything else since 2015! The covering text tells readers that “these are average costs” and that “general living costs are much cheaper”.

Students there have apparently been spending £45 a week on food, laundry and toiletries for eight years, “social” costs are still £30 a week, “travel home” costs are stuck at £200 a year, “bills” have been £15 – £25 for eight years and “extras” have been £10 a week for all that time.

I’d move house if it wasn’t for the fact that that’s absolute twaddle.

Maybe the assumption is that having the UK’s most generous undergraduate maintenance system somehow makes the issues less important – but not all students are home domiciled, not all are undergraduate and not students in Wales are from Wales. Back in 2015 the Diamond Review drew specific attention to student costs – it may well be time to revisit some of the principles.

Travelled to Wolverhampton, worked in a shoe shop

Back in 1995, I was very angry with myself for not working out how much it would really cost to have anything other than a solitary existence.

That’s why I think information on costs that gives real and accurate information rather than information that supports recruitment to a particular university on a false premise is so, so important.

It’s why finding some of the laughably poor cost of living pages on university websites, 18 months into a cost of living crisis, so maddening.

I don’t really care if it’s accidental or deliberately misleading. But using figures from 2019 or telling students university will cost x when it really costs y I just think is appalling.

Whoever you are – if you have any level of involvement or adjacency to cost of living information going out from universities, get involved.

Ask where the figures come from. Ask if they’ve checked with real students (how any university in England with an access and participation plan gets away without doing so is beyond me).

Find a way to collaborate with others in your city or region to get some accurate costs information – avoiding the often wildly different estimates that sometimes apply to the same places.

Remember that costs differ by programme or subject of study. Remember to warn students that inflation – especially food inflation – is still very high indeed, and will continue to be for the foreseeable future.

Put some pressure on the DfE (and Welsh Government) to publish the figures it’s presumably sat on from the extensive Student Income and Expenditure Survey it commissioned in 2021.

Above all, ask yourself this. In a drive to get people to come, and to come to us, have we made it sound just that little bit too easy? You’ll sleep easier at night.

As ever, some really good food for thought in here. I’d add one more to the list: in a world where financial hardship is a major impediment to student achievement (either via completion or attainment), being honest about costs of study might in fact improve B3 and APP outcomes and that’s aside from the moral and C1 / CMA obligations on providers. That said maybe further work could usefully done to support providers to access high quality information on living costs and, in a manner to financial SORPs, to develop guidance and expectations on how to present forward cost expectations… Read more »

Really good article. Thank you. Where would you recommend going for good information on student costs? As I work as a Widening Access Officer (rather than in marketing) I’ve taken to using average costs from the Student Money Survey, but would be interested to see if you have any other trusted sources.