Of course it is true that income from international students enables more home students to study at university rather than “crowds them out”.

Yes it is true that undergraduate courses with foundation years enable students with lower grades than those entering directly to get onto them – regardless of whether those students are home or international.

And of course it is true that schemes that enable home students from disadvantaged backgrounds to enter HE through foundation years are even harder to run these days now that the government has resolved to slash funding/fees for such schemes.

The original version of the Sunday Times’ splash on international students was even framed around the idea that “Cash for Courses” is bad – enragingly ironic when the whole system is set up around fees:

That Sunday Times piece? It’s just not fair.

By the afternoon, the Telegraph was reporting that ministers have waded in:

NEW: The Department for Education says it is “urgently investigating” reports that UK students are being asked to meet higher entry standards than international students

Ministers have held discussions with the university sector this afternoon

— Louisa Clarence-Smith (@LouisaClarence) January 28, 2024

And yes, that’s almost certainly performative. But at the end of a fortnight in which the National Audit Office uncovered evidence of organised crime and fraud in university admissions, and the universities’ regulator found a cohort of international students recruited by a third party without meeting the standard English language requirements, the sector should probably breathe a sigh of relief that the ST’s iteration was so easy to debunk.

It is now surely now long past time that proper regulation should be imposed and enforced on how higher education is sold – and while the antics of agents (both international and domestic) are in focus for now, the sector’s “consumer when we’re selling to you, partner and learner when we’re (not) delivering what we promised” positioning is still on pretty shaky ground.

Outside of the agent thing, there really isn’t much to see here. But while it cheers us all up, the detail in and the debunking of the Sunday Times piece is not really the point. It’s the mood music of unfairness that matters the most – and feels to me like the most undercooked aspect of the sector’s response to the general feeling of negativity around higher education in the commentary to date.

Uneven playing fields

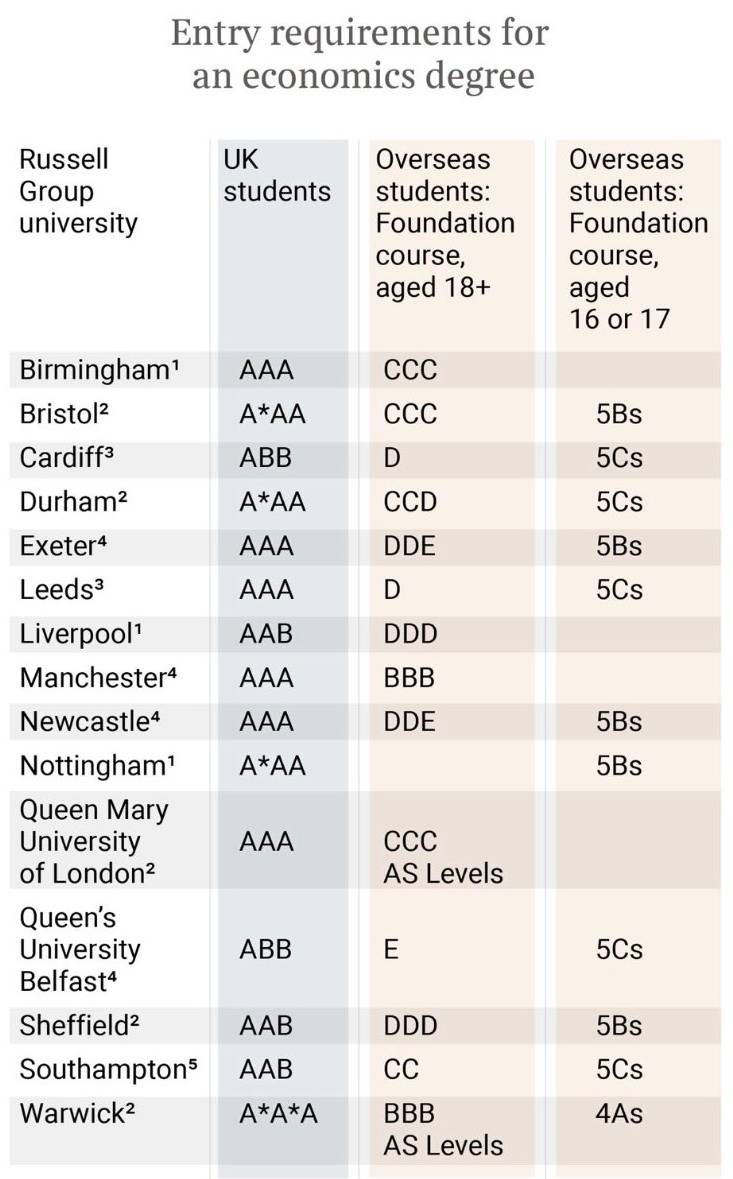

In the most selective part of the sector, it’s charts like this that get the pundits red with rage.

There might well be a column missing – the one that shows the grades that home students from disadvantaged backgrounds have or might need to get onto domestic versions of foundation year access schemes – but even then, if you’re not in one of those postcodes or in one of those categories, your kid won’t be getting in.

It’s why responses to stories in Scotland pointing out that without international students paying for their place in the ancients, it would be even harder to get in, haven’t worked – and it’s why the sector seems to have been consistently caught out by “scandals” surrounding unconditional offers and complaints over Covid, and the government caught out over anger over Covid A Levels.

Outside Scotland, despite having moved to a system which pretty much enables anyone who wants to study to be able to do so, it still suits the sector to maintain a scarcity illusion over who gets “in” and “wins” a place. So when that’s coupled with league tables and mission groups designed to signal which of those places is “better” than others, the sector will always face questions over whose raffle ticket seems to have a better chance of being drawn the further up the tables you go.

And in Scotland the problem is worse – because there really is a fixed number of home students that can get in. And so regardless of the way in which international students support things at a system level, or of the way in which prior schooling or background can improve or deflate your odds, when the stated standard for “winning” a place is X, and yet there is evidence that internationals can buy or domestics can plead poverty to instead enter with Y, there will be claims of unfairness.

Tentatively, the commentary that surrounds these stories at the edges will proclaim that the incentives, the system design and the realities of underfunding mean that these things are inevitable.

Yet in a political context that demands that students or graduates make the lion’s share of contributions to funding higher education, few argue that the easiest way to have more students study the more “elite” courses is to have more middle class families and graduates pay more. And there’s no point universities saying that the system is unfair when said unfairness seems to be being gleefully passed on to the punters.

Even in Scotland where commentary outside of the SNP tends to be opportunistically pro-fees, few would be willing to face the fact that even with fees, richer students on the most selective courses would graduate with less debt – and their returns in the labour market, coupled with a system designed around “fees and debt” rather than tax, would see them contribute least as a proportion of income anyway.

Money talks

Neither access to higher education, nor the returns from it, can reasonably have been said, historically, to be “fair”. Money – in private schooling, admissions help or now via international fees and agent incentives – has always talked.

And the sector’s egalitarian, pro-equality instincts will always be able to find ways to reason that whatever unfairness lingers in the system, it would be worse without the schemes that are thrown at it as evidence of growing unfairness.

But while a level of unfairness over entry has always been present, at least universities were historically able to argue that in getting in and getting on had rules designed to be “fair”.

If you got the grades, you got in. Home students pretty much all paid the same amount in fees. International students paid only a bit extra to cover the costs that government wouldn’t.

Cross subsidies by subject or need for support were at a level most accepted. Everyone had access to pretty much the same sorts of attention and facilities regardless of the course or campus they picked.

Housing was relatively easy for all students to access, and while there have always been students who worked, it wasn’t impossible for most to achieve a decent and rounded student experience.

If that sounds like rose-tinted twaddle, then you’d be right – there were always plenty of inequalities in the experience once students were getting on to help compound those that presented while trying to get in.

But as the central funding gets tighter per student – driven by governments worldwide trying to kid themselves that the experience of and benefits of elite HE can be delivered on the cheap to the mass – those inequalities and thus the perceptions of unfairness are getting, and will get, worse.

Charging all home students regardless of support needs £9k for a UG degree is “fair” if the government tops up the students who need more help with premium funding. But as that funding falls, the more a university has to spend student X’s money on student Y’s support, the more it feels “unfair” to both student X and Y.

Charging all home students regardless of subject £9k for a UG degree is “fair” if the government tops up the expensive to teach subjects with extra funding. But as that funding falls, the more a university has to spend student X’s money on student Y’s subject, the more it feels “unfair”.

Regulating the cost (in Scotland for Scottish students down to £0) of entering HE is “fair” if everyone who hits a certain ability level is given a place. But the more that the subsidy involved in a universal “price” is undermined by its cost, the more that the vast differentials in experience feel “unfair” too – because the selective parts of the sector have to pack them in, and the less selective parts have to abandon subject choice and experience immersion.

Then as graduate “debt” levels pile up in annual statements, the unfairness of having implied that it’s a debt you’ll ever pay off gets worse – and while reducing interest rates while extending the loan term in England will help the headline figure look lower, you just wait until they’re all still paying off into their sixties.

And for international students, being told it’s amazing and affordable only to find you’re paying double in fees and yet can’t afford to do anything other other than double up in a room – and then being blamed for it all – is going to feel especially unfair.

If the sector’s general position is that the entry requirements are equivalent for international students, it then might want to explain they seem to do achieve at consistently worse rates than their UK counterparts.

Maybe it is all unfair

When anyone says that HE is unfair, the easiest things in the world to do are to blame politicians, point at how hard someone else is having it, or ask those making those claims to have a thought for how unfair it is on universities to be blamed for the problem. But they all, ultimately, sound tin-eared – and suggest a profound lack of empathy.

The point is that higher education is slipping into a cauldron of unending and intensifying unfairnesses – between those from different nations, between those of different backgrounds and nationalities, between those with and without health or support needs, between those with passions for different subjects, and between those with different access to cultural and financial capital.

And it’s a reasonable bet that they’re spending less time with each other too – as the bifurcations between student characteristics manifest more clearly inside subjects, housing, facilities, social activity, mode and provider type intensify, so the solidarity between and shared understanding between students whose experiences and backgrounds differ diminishes into respective and bitter claims of unfairness.

Some of those claims will be debunkable, and some will be breathtaking in their hypocrisy. But the sooner that the sector realises how unfair it has allowed itself to seem, and the sooner it collectively starts to discuss ways to address it, the sooner it can start having a proper conversation with the public about what to do about it – and how much fixing it might cost.

“If the sector’s general position is that the entry requirements are equivalent for international students, it then might want to explain they seem to do achieve at consistently worse rates than their UK counterparts.”

Well that is obvious isn’t it: it is those vile racist academics who give lower marks to international students. Senior managers should take over the awarding of marks to students, academics can simply not be trusted to do this.

Fairness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. We could argue forever and never reach a consensus. I am pleased the debate has got down to the level of individual courses for specific subjects at individual Universities to help more people better understand what is going on. This is really important, particularly for high cost to deliver courses, when we look at the benefits of having Universities and degrees from the viewpoint of “society” at large and individual students. Let us look at Medicine. The loan is £9,250 per year per student, around £37,000 for the 4 years… Read more »

Fitting that an economics degree was used to demonstrate what is going on here! My crystal ball is telling me that in future we’ll see different fees for different subjects 😉

I think that the Times splash’s normie analysis is basically fine. They are looking at it from the perspective of a mid-to-upper class rank indie school student who is worried about the chance of getting onto their preferred program. And, indeed, it is much easier to do this if you’re not a home student, because there are relatively (and sometimes even absolutely) more places available at full price. Insiders to the sector make a number of correct points: – UCAS asking rates are the wrong units to measure selectivity, since the rationing mechanism is the price cap, not the asking… Read more »