A plausible scenario is emerging where the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill never becomes law, and thanks to the transport chaos of Storm Eunice, I’ve been thinking a lot about where that would leave us.

In England, it would remain the case that the Office for Students (OfS) regulates compliance with its regulatory framework, which contains a set of public interest governance principles that include clauses on both academic freedom and freedom of speech.

A paragraph in a forthcoming strategic guidance letter from ministers to OfS could quite easily cause some enhanced focus in this area, even if some of the sillier stuff on a separate complaints procedure, a legal tort and directly regulating SUs was to disappear off the table.

And anyway, it’s not as if the “issues” encapsulated in the free speech debate are only present in England. There might be less of a desire to legislate and condemn universities in our devolved nations, but there are just as many tensions. After all, almost every free speech issue is also an equality and diversity issue.

When making the case for the bill, ministers have been keen to argue that one of the differences between the current Education Act 1986 duty and the proposed new duty on universities would be about “promoting the importance of” freedom of speech.

I’ve heard legal arguments that dismiss the idea that there is real or practical difference between the two duties. I can also imagine one of those online induction modules being developed, to be taken just before or just after the ones on consent and EDI, that allows a university to tick the relevant regulatory compliance box.

But let’s imagine for a minute that there is, in fact, a real problem on campus that needs solving. And let’s therefore try to work out what “promoting the importance of” might actually mean if we were taking it seriously without just ticking a box.

Let’s also imagine that this was all actually about higher… education.

Riding on any wave

Generally, it’s always been clear to me that lots of the “cancel culture”, “snowflake” and “no platforming” stuff is either made up or unhelpfully exaggerated. It’s also clear – exemplified by articles like this in the Boston Globe – that students are not obsessed with the issues at stake in the free speech debate:

What they are worried about… are their GPAs and resumes. They struggle with mental health challenges and widespread feelings that they don’t belong and of alienation from peers, the academic agenda, or the ethos of their institution.”

But what I think is interesting about that framing and the piece more generally is that at least in part, those concerns that students do have are about the relationship that students have with both other students and wider society. And that’s very much at the other end of the see-saw of the free speech debate.

Students complained that others did not truly understand them, and as a result, they separated into groups of students that are most like them. Some also believed that their peers didn’t know how to conduct productive conversations about issues of race, which often led to frustration. Some talked about blatant discrimination, intolerance, and general insensitivity, aimed especially at minority groups.

As I say, almost every free speech issue is also, from another perspective, an equality and diversity issue.

Let me give you an example. I can find little evidence that “no platforming” is on the rise, or that students are somehow “less tolerant” of diversity. But one thing that does appear to be true both in SUs and in universities is that students are increasingly reaching for “authority” and formal procedures to fix disagreements over behaviour that they regard as unacceptable. They are also increasingly participating in the rapid and decentralised online accountability of others.

To the boomers, this is all baffling. Their fights for freedom in the 1960s and 1970s were all about resisting the authoritarian tendencies of universities to apply discipline. Now today’s activists crave it to resolve rows that as far as the boomers are concerned would have been sorted out over a coffee in their day. The pile-ons make little sense either – they don’t follow hard-won rules of natural justice and don’t allow for anyone to make a minor mistake.

Yet to those in the middle of all this, it all makes lots of sense. For them, one boomer’s “freedom of speech” is really freedom to belittle, oppress or harass. They’ve had quite enough of that on social media since their tweens, thank you very much. So yes, they are demanding the environments sold to their parents as “safe” take action to make that real. And if not, they’ll take matters into their own hands. It’s hardly as if the formal accountability systems of justice and the media or parliament are holding people properly to account.

That is the luck you crave

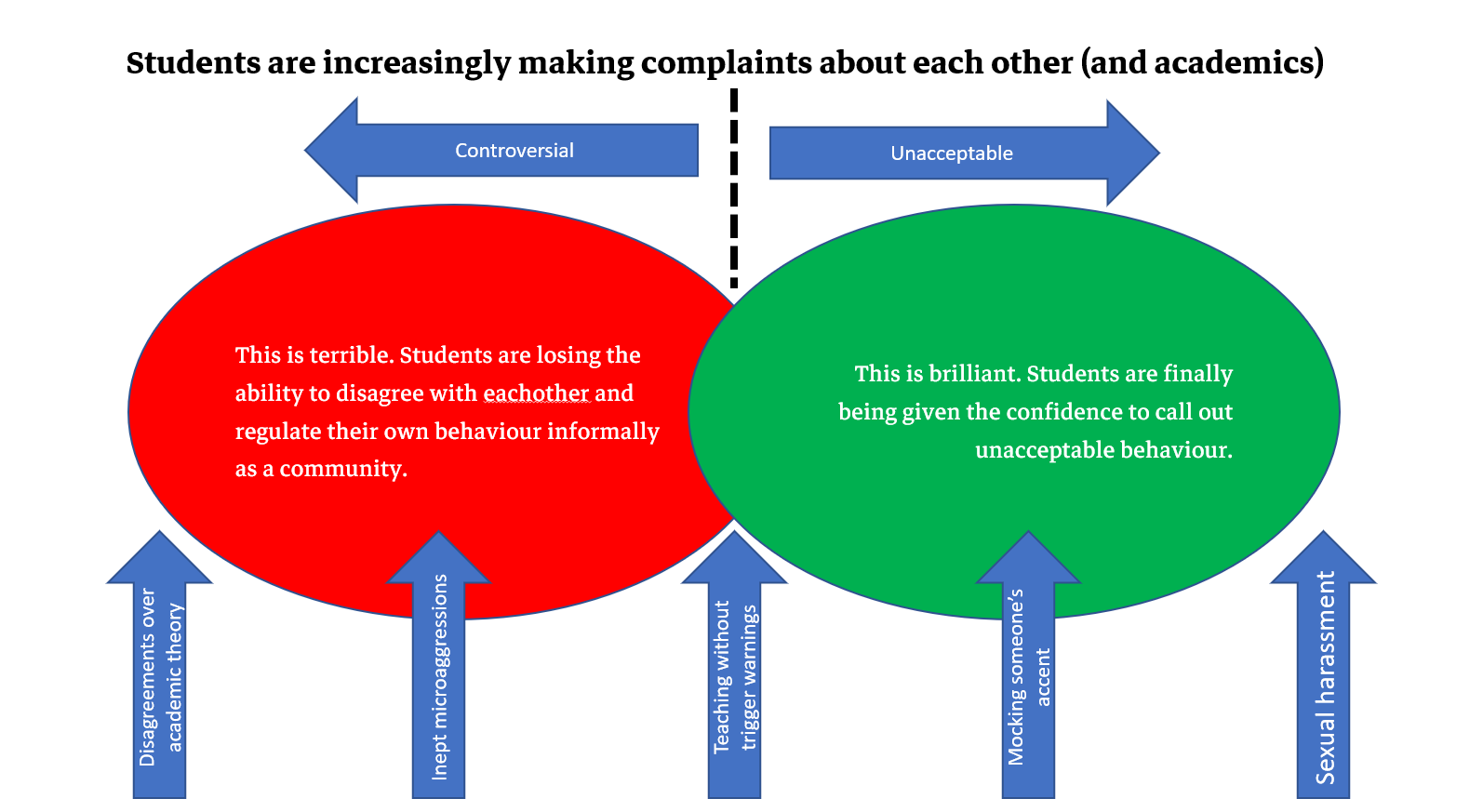

As such, for me there are two ways that we might therefore frame what is going on this rise of a particular kind of “complaints” culture on campus.

You can argue that it is all terrible. As students and young people spend less and less time with each other (especially with people “not like them”) in their online filter bubbles, it means that on the surface they appear to value diversity, but in reality they don’t develop the skill of building “bridging” social capital – or indeed any real empathy with, or capability to discuss difficult things with, others. That is especially bad as it is something that we imagine that attending a university develops and delivers.

In this frame, students are losing the ability to mediate and regulate their own community, which is a problem for the future.

On the other hand, you can argue that the rise of a complaints culture is great news. It is surely fantastic that (some, more) people now feel confident to raise incidents of abuse and harassment through formal procedures – because when we left all of that to an informal “community”, the harassment thrived and was never meaningfully tackled.

Students – especially those harassed or marginalised – gain the ability to access the community – fantastic for the future.

On the face of it, these two positions are hard to reconcile unless you attempt some kind of venn diagram, but even then there will always be a shifting debate about what is unacceptable to say and what is merely controversial – the precise position of the dotted line isn’t shared, and the positioning (and definition) of the arrows is hotly contested.

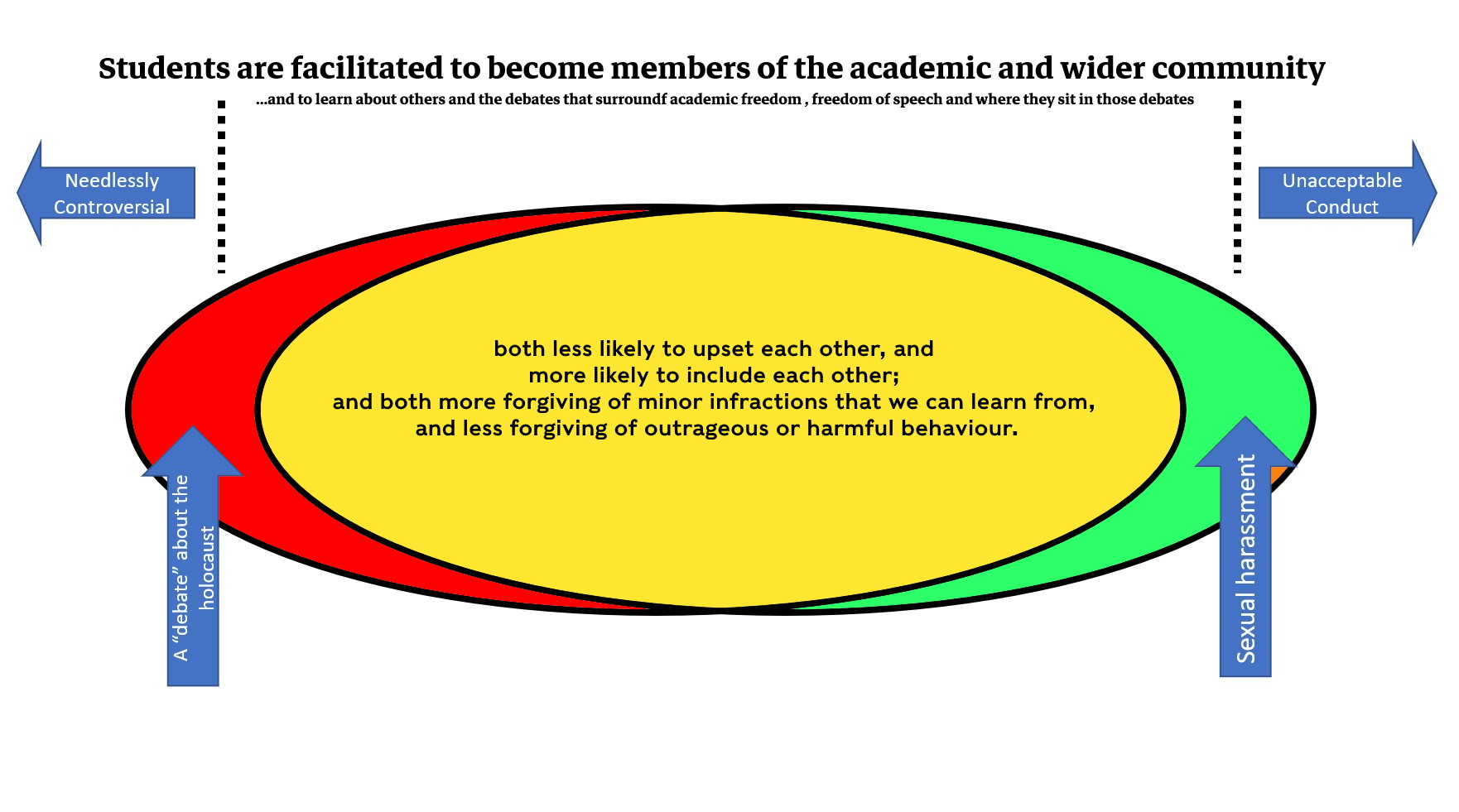

But it seems to me that both positions described above can be true outside of the extremes, that we ought to attempt an integration rather than see them on a continuum. Surely, the argument goes, we want both to develop students’ ability to exist in a community, and for everyone to thrive in it and access support and justice when they can’t.

They don’t believe it now

So what might be done? Here’s a scenario. Let’s imagine a drunk first year undergraduate student grabs the mic at a Freshers’ SU Karaoke event and describes someone else via the use of a homophobic slur.

These days, that student may well a) be “cancelled” online quickly and in very harsh ways (the “mob justice” thing) and b) may well have to face a formal complaint thanks to better publicity and awareness of those complaints.

You can argue that that is bad as the student – possibly from a background where that was just “banter” – didn’t know any better. How are they supposed to learn these days?

You can also argue that it’s good – because in the old days, the homophobia was pervasive and at least now it’s being tackled. LGBT+ students will feel safer if they see the disciplining, the student won’t do it again, and the public nature of the condemnation means it warns others off from doing it too.

A formal complaint rolls into the SU and or the university. It is true that a formal process may take time. An investigation and panel hearing would represent a kind of punishment in and of itself – when an employee is suspended at least they’re on full pay, but it’s not clear that what a student loses is replaceable.

And if the university or SU finds that the student isn’t “guilty” of a conduct code breach, the “mob rule” thing is especially hard to tackle. A university even thinking about punishing those who would condemn a student’s behaviour anyway would need to think twice.

But here’s my question. Why have we let it get this far in the first place?

They just think it’s stupid

Here’s another. An academic is due to speak on a topic that is neither obviously contested amongst students nor obviously one on which there is a universal view in wider society. Students generationally see the matter as clear cut as antisemitism or outright racism, the press thinks there ought to be a free for all “debate”.

A petition circulates calling for the event to be banned, and a complaint is submitted about the topic of the talk when compared against the university’s values. During the campaign, some students are downright rude – and the academic indulges in outbursts over the issue that are profoundly unhelpful. The academic is removed from teaching duties, the students are doorstepped by the Mail on Sunday, and everyone is right. Out comes the process book, which used to make it all better, but somehow makes it all worse.

Again, here’s my question. Why have we let it get this far in the first place?

So got anything?

Many of the competencies, skills and values that students are supposed to develop as a result of higher education participation are developed by accident, and many of the ones we really cherish are about how students treat each other.

But given they’re not part of any curriculum, and barely a deliberate part even of organised activity, there’s not historically been any particular problem if you fail to develop them. They have been a “nice to have”, don’t impact your degree classification, and have traditionally only resulted in a clip on the ear if you egregiously reject them.

The problem is that that obviously doesn’t cut it in a modern, diverse world where the stakes are higher, and where accountability is distributed via social media, and is both brutal and swift. My favourite rule on assessment is don’t test what you haven’t taught. So whether we’re talking about codes of conduct that must demonstrate “Zero Tolerance” or the public accountability that students will face if they get something wrong, why are doing just that on student behaviour, conduct and speech?

If students are joining a diverse community that is more complex to navigate than it was in the past, the question for me is how we help them do that – especially if “make mistakes along the way” is less of a viable option for sound inclusion reasons.

Anyone could have done

If you think about it, one of the remarkable things about higher education is that values which can feel like they can conflict (like equality and diversity and freedom of speech) are not properly discussed or practised early on. And causing students to interact with others that are not like them is not really done either.

An online tick box arse cover EDI module on microaggressions in August is some distance from a group of students facilitated to talk about difference and the sensible boundaries between that which is controversial and unacceptable to say and do.

Where that gets us to is that I think “being a student” is hard. Partly because we’re more diverse and partly because we often recruit on potential, there needs to be time in the early part of a student joining a university community that facilitates and enables these discussions.

Carving out time to do this properly would be hugely beneficial, as would a proper grounding in the academic discourse around both free speech and EDI, and the student’s individual relationship to those concepts in the context of their course, cohort and clubs.

For the avoidance of doubt, this doesn’t mean that I’m proposing to “both sides” trans rights, or suggest that someone facilitates a “debate” about BLM with some kind of GB News character at a campus event. But I absolutely am suggesting that students spend time listening to, engaging with and analysing the origins of others’ (different) perspectives on a whole range of things – with people both within and outside of their own generational community.

This isn’t about “learning how to debate” or “learning how to disagree”. It’s about understanding the debates, and both why and what happens when people disagree.

We should see a programme of activity of this sort as essential, and done well it would make students both less likely to upset each other, and more likely to include each other; and both more forgiving of minor infractions that we can learn from, and less forgiving of outrageous or harmful behaviour.

We should also see it, in part, as a response to the collective reality of a deeply anxious student body. We are seeing a lot of fight, and a lot of flight, over conflict on campus. Given anxiety is a fear response caused by isolation or alienation and fear about the future, taking steps within the curriculum to address both of things in the context of these debates will help students handle them when they impact on them.

All of this would help combine freedom of speech and freedom from harm, rather than forcing students to pick a side – and would cause both consensus over where the dotted line should be, and integration of rather than choosing between the two positions.

It would, in short, make students better citizens of their university community. But we have to choose to cause it to happen instead of hoping it happens by accident just because they’re all in a hall of residence or seminar group and all from the same social class.

Is it cool that these days there’s some vegans studying alongside the farmers at Harper Adams? It is. Should the integration of those communities be left to informal chance? I doubt it.

Who would’ve cared at all, not you

There are all sorts of people that could make all of this happen. Students should take a lead, and I think academics have a role to play in it. And before someone dives into the comments, I don’t think it should manifest in “make this happen” being dumped on module leaders – in fact, I think some of the academic subject-based education should be reduced to make space for it.

I do think that this is “higher” education stuff. It’s not a ticky test to be passed on definitions, or an online module with a couple of scenarios. It’s a series of interventions which are about the complexities and boundaries of academic and community conduct – about living together, and learning together.

It requires a grounding in the issues at play, an understanding of diversity and difference, at the very least a reflective essay at the end to pass, and maybe some authentic assessment along the way. And students should be able to fail it and then not continue as students.

I don’t know, for example, where I stand on the legitimacy or acceptability of “acting out” behaviours from those that are on the sharp end of marginalisation, especially in the context of a deeper understanding of the impact that higher education has on people as well as knowledge. I can see why some argue “excuse” and others ”justification”. But I do know that I want those that call themselves “higher education” students to be able to demonstrate an understanding of that debate, because it’s something that has become so central to the higher education experience. And so on.

Ever since the demos of the seventies called for students to be included on disciplinary panels, it has always mattered that students understand why there are rules, help set them, help enforce them, and know where, how and why some of them conflict in practice. My guess is that positive progress in this area depends on reminding ourselves of that – and that students crave “higher education” on these issues – rather than putting up posters to tell students what the rules are when not having those rules never did us any harm.

An important piece. I believe that some of this gets pushed from staff to their students, in terms of what is acceptable in their personal opinion but also crosses over into some professional statutory body regulations e.g. Social Work students are told by SWE that they HAVE to accept certain views, which has and continues to be an evolving picture over the years. So a Social Work lecturer will have a very specific view of what this “better citizen” should look like, and as you say, it very much is a dichotomy of freedom of speech vs EDI matters, and… Read more »

Interesting. This is something noted in the Univeristy Mental Health Charter; the need for balance between social cohesion/ belonging and difference/individualism. Many universities now have a conflict mediation service so there are possibly skills to build on there for a more upstream/ preventative approach.

“Surely, the argument goes, we want both to develop students’ ability to exist in a community, and for everyone to thrive in it and access support and justice when they can’t.”

I can recommend this report on Campus Free Speech from the Bipartisan Policy Centre in the USA https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/a-new-roadmap/. They propose practical ways to develop precisely this overlap and call it ;inclusive freedom’.

The report also contains helpful table-top exercises that staff and students could use to explore these issues, and as rehearsal for when conflicts arise.