It’s been a funny old year, hasn’t it?

Back in the summer we were concerned about the fragile state of sector finances. Depending on your favourite forecaster “a handful”, “eight”, or “twelve” English providers were at serious risk from a downturn in income and an upswing in costs due to the pandemic.

And yet, here we are in the summer of 2021 and everyone seems to still be standing. And, even better, OfS says:

Judgement remains that the likelihood of multiple providers exiting the sector in a disorderly way because of financial failure is low at this time

But at the same time, net operating cashflow halved between 2019-20 and 2021-22 – from 8.4 per cent to 4.2 per cent.

What happened?

Clap for bankers

A decline in income and a rise in costs leads to problems with liquidity. Though there’s nothing wrong with the fundamentals, an external pressure like Covid-19 puts a great deal of stress on a provider.

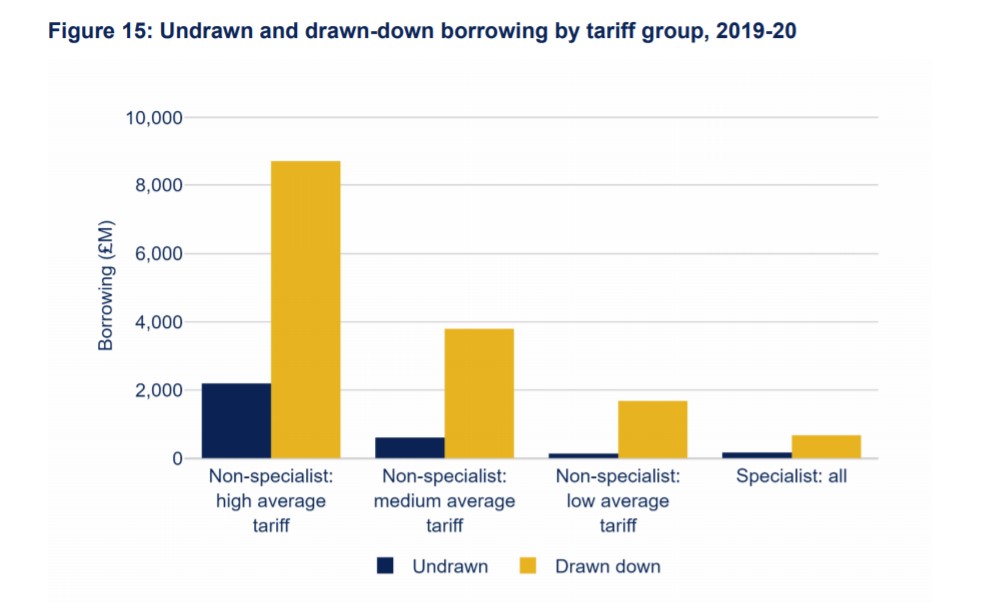

So we’ve seen a sharp rise in borrowing – including from government backed loan schemes, and emergency short-term finance facilities from banks. Not all of this has been used – and better than expected recruitment, among other things, means it is not expected that they will be used.

The expectation is that the amount of borrowing as a percentage of provider income – currently at a historically high level – will decline from 2022-23 onwards. But clearly different providers have different levels of exposure – we don’t get full details at this point but we do get a plot by tariff group. This tells us, for instance, that 25 per cent of high tariff providers are borrowing more than 35.3 per cent of their income. And 25 per cent of medium tariff providers are borrowing more than 47.8 per cent of their income. Which is quite a lot.

This might seem counterintuitive if you are sitting in a provider being told there is no money left – why wouldn’t providers take up borrowing they already have permission to use? Short-term finance (like the government “support” loans) is good in an emergency, but it is very expensive to repay. The balance between pain now and more pain later is just one of the unenviable decisions your finance team has had to advise senior leaders on this year.

Here’s the actual and projected expenditure for the sector – note in this context the expenditure on interest and other costs of finance.

It shoots up between 2018-19 and 2019-20 – the latter year being where most of the pandemic related borrowing happened, with revolving credit facilities being accessed. You’ll note the projections are that payments on interest are expected to drop in the years to come – no university wants to spend money on interest payments that it could spend on staff salaries in the years of expansion to come so the priority will be to get these new short-term loans paid back quickly.

Income from investments and donations are expected to fall and stay low, and we can expect continued reduced student movement, the possibility of more students dropping out, and reduced income from commercial activities like accommodation and catering.

For these reasons, many providers have deferred capital expenditure in anticipation of continued financial risk – capital spending will increase from 2020-21, but it will remain below pre-pandemic levels. Many providers will be rethinking capital and estates strategies to keep the overall cost of borrowing down.

Forecasts and students

Those years of expansion to come. Yes, that’s more students, and thus more fee income. It’s traditional for financial forecasts submitted to OfS, and HEFCE before it, to be wildly over-optimistic in recruitment projections and this year does not disappoint.

So we are looking at a projected 12.3 per cent rise in home students, and a 29.5 per cent rise in international students between 2020-21 and 2024-25 – in financial terms that’s 14.4 per cent and 46.6 per cent rises in fee income respectively. EU recruitment is projected to decline by 34.8 per cent over this time, with parts of this feeding into the rise in international fees following the removal of student finance eligibility post Brexit.

All of this follows a projected reduction in overseas fee income forecast for 2020-21 – as the students in question are already here we can take this as fairly likely. Looking to next year UCAS indicates a cheering overall increase in student demand. OfS notes, prudently, that fee income forecasts are based on the assumption of no material changes in the English student funding regime. DfE and the Treasury may have other ideas.

Note here that course fees represent between 55 and 57 per cent of overall sector income. Again, this is variable by provider, but the impact of a cut would be felt everywhere.

Risk register

Fee cuts are not even the only risk on the horizon – OfS notes the difficulties that would be caused by new Covid-19 variants and more restrictions, a slower than expected global economic recovery, and continued pensions sustainability concerns.

Indeed, the sustainability of pension schemes is a “significant concern”. This goes beyond the sector, we’ve seen contributions from employers and employees grow for both defined benefit and defined contribution schemes all over the economy. The USS valuation process is a particular problem for some HE providers – recent events have – in the understated words of the report – “reopened the difficult debate”(!) which means that there are longer term sustainability risks and shorter term risks from industrial action.

We get the traditional warning that growth forecasts “may appear ambitious”, though this is tempered by the prospect of an expansion in online delivery meaning that recruitment capacity is no longer tied to estates. The thinking is that the emergency online provision of the last year and a bit have grown capacity – my fear is that emergency contingencies are being confused with a pivot towards a very different marketplace without any evidence of widespread student demand.

Data notes

Data comes from 226 providers (153 based on the traditional 1 August – 31 July financial year). The pool includes providers that don’t receive OfS funding, that were registered with the regulator at 24 May 2021. Nothing on FE colleges (this analysis is done by the ESFA). Data includes two years (2018-19 and 2019-20) of audited financial accounts for most providers, and forecasts through to 2024-25. Not every provider submitted the full forecast.

As usual with these things we don’t get very much data (even on an aggregated level) to conduct our own analysis. Even the sparse graphs in annex A don’t merit actual data tables – much less tables in a reusable format in compliance with the Code of Practice for Statistics – so we do have to take OfS’ word for a lot of it.

Most of the analysis splits the data by tariff group – there are three major groups: high, medium, and low tariff – plus a separate group of specialist providers. A further group of 21 “unclassified” providers is excluded from peer group analysis but is used in the wider sector analysis.