In any sensible world two new reports out on the state of the UK’s student accommodation market would trigger an emergency response.

Ministers would be dragged back from holiday; emergency task and finish groups would be formed; Universities UK would be telling students not to attempt to enrol without a bed.

But this is no sensible world – and it certainly feels like we’re hurtling towards a full-blown student housing crisis without anything resembling a plan.

Especially when the big headline is that the UK’s university towns face a shortage of 350,000 beds this coming academic year.

Crowdsourcing

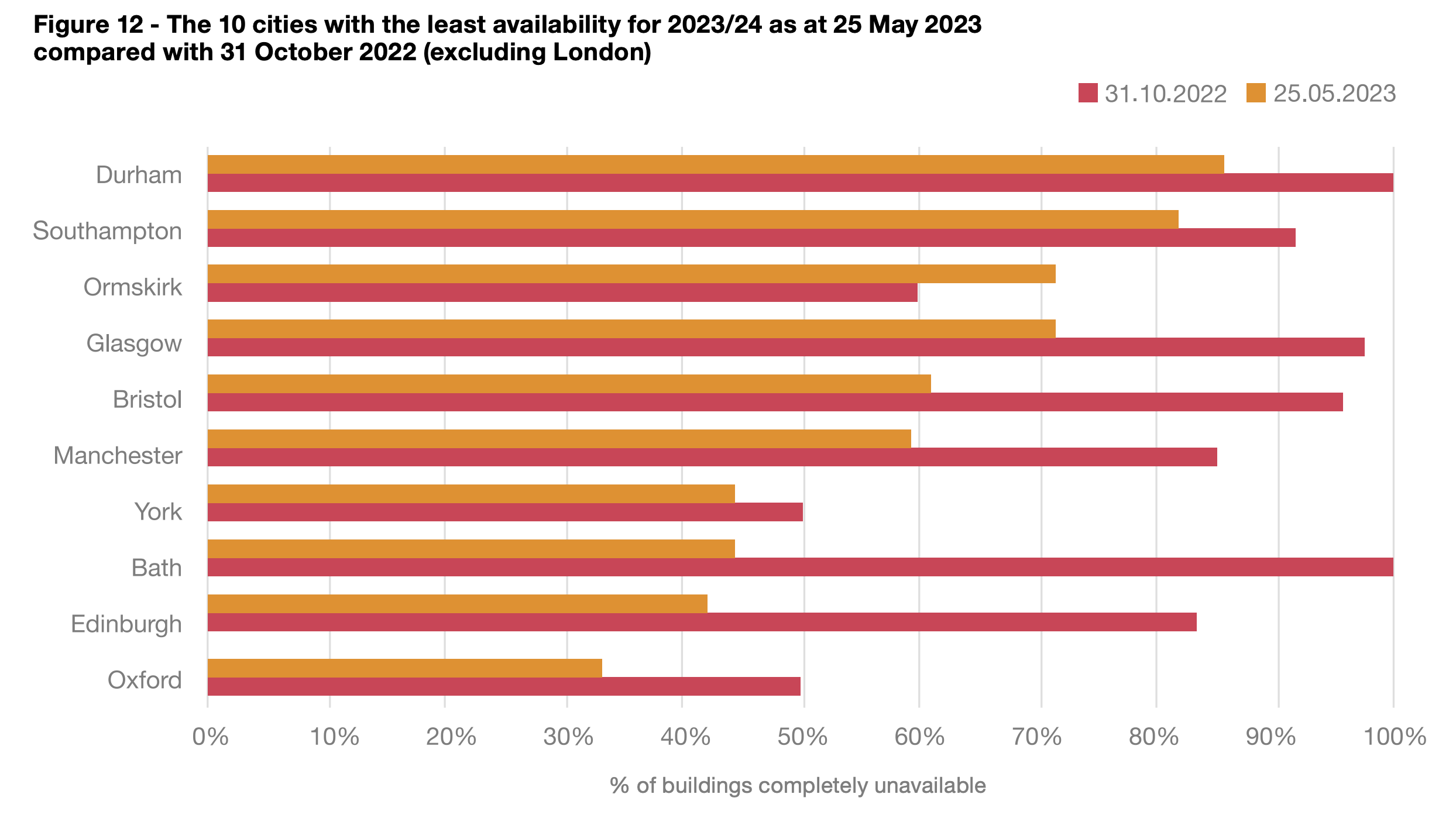

PWC’s Student accommodation: Availability and rental growth trends report takes data from StudentCrowd and extrapolates trends in the accommodation booking cycle and rent increases for privately-owned Purpose Built Student Accommodation (PBSA) to generate a list of the ten cities with the least availability for 2023/24:

Demand driver #1 is international students – where the UK saw an increase of c.77 per cent in FT students in the four years to 2021/22, with both OfS HESES figures and Home Office visa figures suggesting that growth has continued this year.

PWC puts it like this:

We can expect to see continued growth in the numbers of international students given the strength of these [India, Nigeria] markets. Many institutions will also see this growth as an important mitigation to the financial pressures caused by the freeze on the domestic fee cap at a time of significant inflationary pressure on cost base. The recruitment of international students will therefore offer the opportunity to deliver improved margins needed to subsidise domestic teaching and research activity.

It reckons that the ban on dependents from January 2024 may dampen some of the demand – but that still means that this September if anything we’ll see a surge in demand both for traditional single occupancy bedspaces and family accommodation as students try to get in before the ban.

Then there’s domestic demographics. Home domiciled applications might be slowing somewhat, but the number of 18 year olds will continue to rise until 2030 (in England and Wales) and until 2026 (Scotland and Northern Ireland).

That growth, of course, isn’t even – with what PWC calls a “swell” of student numbers in certain cities. Student enrolments in Glasgow (across all its universities) increased by 18,500 students since 2019/20 AY, with increases of 10,500 and 10,000 students in Bristol and Manchester respectively.

Over time, PWC reckons we’ll see a redistribution of students across a wider set of locations and providers, increasing pressure on other locations that are not yet quite at crisis point. In other words, the crisis will spread.

My mortgage has gone up

On the supply side, estimates vary on the contraction in the Houses in Multiple Occupancy (HMOs) market – here PWC quotes a DLUHC report claiming that the number of HMOs in England decreased by 4 percent between 2019/20 and 2021/22, which could result in a loss of HMOs beds ranging from 57,000 to 95,000.

It puts that down to increased regulation (such as additional licensing and more stringent building regulations) and an increased tax burden on landlords – but most other reports identify soaring interest rates as the key culprit causing buy-to-let landlords with a portfolio of properties to find themselves in sudden “sell up” trouble.

Plenty of local authorities expect PBSA to pick up the slack – but there’s a problem there too. A mix of more stringent planning requirements, soaring costs of construction, a higher bar for safety and sustainability and rising debt service costs means that the pipeline of new builds has slowed considerably – at just the point that the new mix of recruits are more price sensitive than in the past over the current crop of stock.

If all of that was just making it harder to find a bedspace it would be a significant problem – but that mismatch between supply and demand is also inevitably driving up rents.

In PBSA – the bedspaces that local authorities imagine will pick up the slack – Manchester’s rent increases are running at about 21 per cent year on year, Glasgow’s at 19 per cent, and Oxford is up 8 per cent.

Given all of the other cost pressures facing students, and the miserly 2.8 per cent increase to maintenance loans coming for England-domiciled students this September, we can see that the crisis is one of both supply and affordability.

Even where there’s oversupply, there’s evidence of a costs crunch. There are a number of university towns and cities who have places in halls (both university and private PBSA) lying empty – because the mix of students now being recruited to those properties is significantly more price sensitive than assumed by developers when modelling schemes in the past.

Rents up

CBRE’s Mid Year Market Outlook (Intelligent Investment) 2023 has some similarly stark messages. It quotes rent increases at Empiric (one of the big PBSA providers) and Unite at 6 percent and up, and notes that investment activity in 2023 has so far been “subdued” (£544m transacted between January and May 2023, compared to £2.6bn within the same period in 2022) due to a “mismatch between investor and vendor aspirations”.

According to its figures seen by the FT, some 350,000 purpose-built student beds across the UK’s 30 largest university towns and cities are needed to meet the expected demand for accommodation. Tim Pankhurst, executive director at CBRE says:

If you’re in a town or city, rents are going up. There is [private sector] accommodation available but it’s becoming more and more expensive, the private rental sector has seen a big decline in the number of rooms available.

It says that in London alone the shortfall in beds has surpassed 100,000, or half of the expected demand – a 45 per cent increase on 2017-2018.

What is to be done?

Given the scale and urgency of the crisis coming, we might have expected something a little more dramatic than the quote given by Universities UK to the PWC report:

This data, from PwC and StudentCrowd, will provide helpful tools and evidence for the sector to work together to address problem areas in accommodation, and will further provide focus and clarity on this issue for universities, local governments, and anyone else involved in the housing of student populations.

Generally, when universities expand, folk often forget the compound impacts of UG expansion – 1,000 more entrants one September, if held there, becomes 2,000 more students by the following and 3,000 the year after that. As such, given the current rapid growth is in PGT, you’d have thought that the problem is eminently containable, albeit that all the reports tend to ignore the housing demands arising from graduate route takeup. As NUS VP Chloe Field puts it:

The shortage of affordable student housing in towns and cities across the UK will only get worse without universities prioritising a strategic approach. This should be based on supply and demand, rather than prioritising student numbers without considering capacity.

The biggest problem appears to be the continued learned helplessness of the sector over the problem. It’s shocking enough that UUK had to issue guidance a couple of months ago advising universities that:

… it will be important for universities to continue to make regular, realistic assessments of likely future demand for accommodation from their students, and the corresponding housing supply – considering not just university- and privately managed purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA), but also other available accommodation within the local area, the bulk of which will be houses in multiple occupation (HMOs).

If there is a proper shortage in several cities this September, that either means that universities are deliberately recruiting students to places where there’s nowhere to live, or that “continued” qualifier in the first sentence above is a stretch.

It all creates moral duties – to either recruit fewer students, or at least warn students properly (including through careful regulation and monitoring of agents) about availability and price (especially during clearing), both of which end up being traded off against the need to keep sector finances afloat.

Brace brace

The saddest bit of all is the grim inevitability of what’s to come. The bigger university cities will consist of international students and richer home students on the course and university they want, and poorer home students compromising on local because they have to:

[Is it possible to commute from London five days a week?] It *is* possible, but I *really* wouldn’t recommend it. Although it’s only around an hour on the train, door to door it’s more like 2-3 hours each way (depending on where in London you live). This becomes sooo exhausting and will affect your attendance in not only lectures etc., but social activities too which are so important to uni life.

On the way to the big adjustment underway, misled students of all stripe will be the victims – thinking they could afford to live somewhere, but either switching to painful commutes, switching to a university more local to them, scraping together the rent on dangerous part-time working hours to hang on in there, or dropping out altogether.

And when the Renter’s Reform Bill comes back to Parliament, the prospect of proper rights for renters will be easy to trade away on the basis of the landlord lobby pointing out that fixing some of their sharp practices will cause that HMO supply problem to worsen.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again – you can’t have an international education strategy without considering housing, and it ought to be every university’s duty to attempt to ensure that every student it recruits that’s living away from home has a reasonable chance to rent somewhere that’s affordable, safe and of a reasonable distance from campus.

That neither universities nor ministers appear to believe that this is their problem to own, let alone fix, is yet another example of the “system” failing both the students it seeks to educate and the increasingly precarious staff it expects to educate them.

Worth mentioning that Durham’s presence at the top of that PwC graph is misleading, as PBSA buildings account for only around 10% of student accommodation in Durham.