There is an ongoing tension across tertiary education – seen particularly in merged or federated further education college groups over the past couple of decades – between a desire for geographical coverage (good for local economies and good for local access), and the economies of scale you get from operating big, multidisciplinary city campuses.

So when its partnership with a large healthcare provider in India took over the campus and the 800-bed hall of residence at the former Crewe campus of Manchester Metropolitan University, one of the questions surrounding the University of Buckingham’s plans for a new medical school 120 miles from home was whether (and when) it would hit ambitious student numbers goals to fund any financial commitments entered into as part of the deal.

After all, when Manchester Met announced its closure in 2019, vice chancellor Malcolm Press said that it had been evident for some time that the Cheshire campus was no longer academically or financially sustainable for the university. How was a partnership between Buckingham, Apollo Hospitals and a community interest company run by a former city headhunter and Conservative councillor going to make specialist higher education in Crewe work, where Manchester Met had deemed generalist HE unviable?

By the looks of Buckingham’s latest (and late) just-published accounts from year end December 2019 (with no sign yet of 2020 or 2021’s accounts), plenty of questions remain, many of which surround risk – and whose shoulders it rests on.

Withdraw to sustain

Those tertiary tensions are all there in the year-end 2017 accounts for Manchester Metropolitan. It is noted that the long-term sustainability of the campus in Cheshire had been an issue – with the board resolving to withdraw at the end of 2018/19 academic year to better protect the future sustainability of the university as a whole.

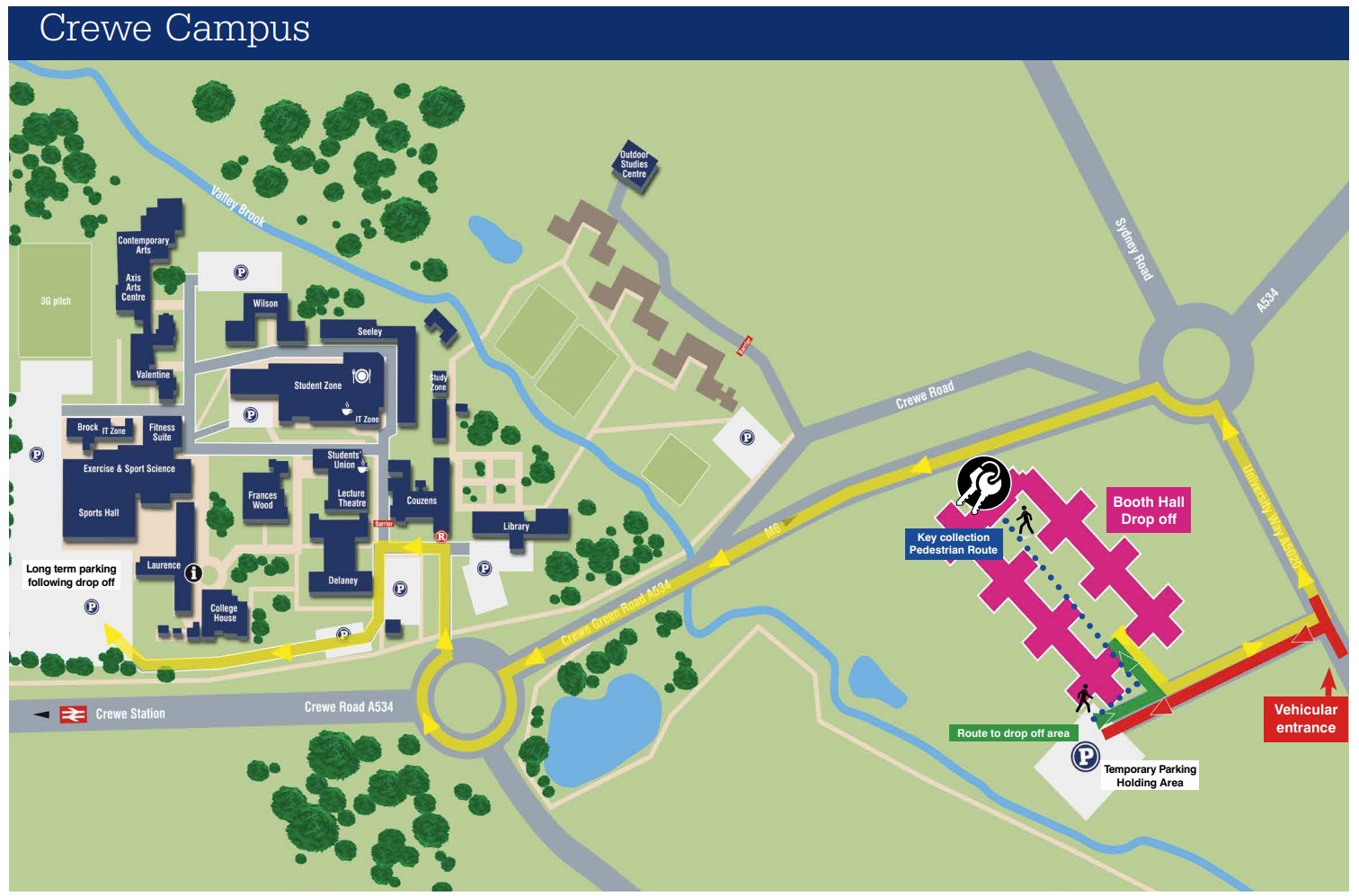

Plenty of restructuring costs and accelerated write downs of campus capital investment were anticipated in those accounts – but not every cost could just be sunk. A thorny issue was Booth Hall, an 800 bedspace student village opened to great fanfare by Bobby Charlton back in 2006. In a special contingent liability note in those accounts, Manchester Metropolitan discloses that the lease on that facility had an unexpired term of 17 years – causing the university to assess “a wide range of options” to work out “the basis of assignment or other exit options from the lease.”

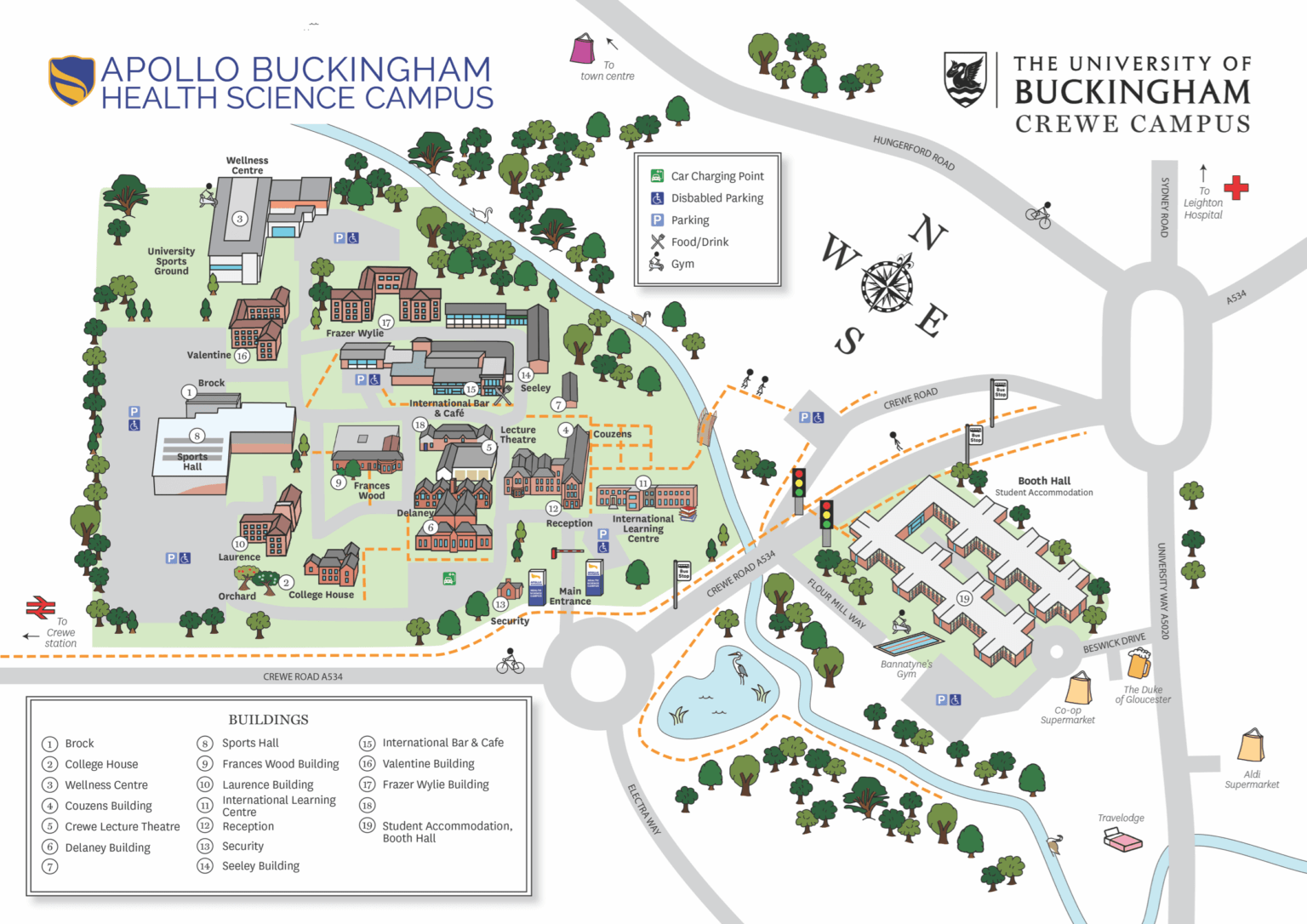

Scroll forward to December 2018, and the University of Buckingham surprised the sector by announcing that it had struck up a partnership with an Indian healthcare provider to take over the 40-acre site, which from September 2019 was to open as a health science campus offering biomedical and podiatry degrees. A Community Interest Company was the unlikely third wheel in the deal, lined up to operate a “wellness centre” for both students and staff – mental health being a key concern in public pronouncements from vice chancellor Anthony Seldon.

“What is my experience of running universities? Absolutely nothing” he’d said back in 2015, arguing that “lazy universities” needed to “raise their game” and learn from private schools. Britain’s first private (albeit non profit) university, Buckingham had been formed by his father, Arthur Seldon, Margaret Thatcher, who was then leader of the Conservative Party, and Max Beloff, its first vice chancellor – and had been talked up as a model in right-wing circles ever since.

Now “education expert, biographer of four prime ministers and honorary historical adviser to No 10” Seldon was forming another partnership – which was to fuse medical education with urban regeneration. “Crewe is an incredibly promising town with huge potential”, he said at the time, with the press release suggesting the scheme would create 500 new jobs via a goal of 5,000 students by 2024 – a big project for a university with around 3,000 students and 400 staff:

If we are able to play a part in the rejuvenation of the town and its surrounding areas, as we plan to do, we’d be delighted.”

That same month, the outspoken Seldon took to the Times to compare the old days – when financially failing universities were bailed out – with the new regime, when providers like his might have to ride to the rescue to protect provision for the poor:

A harbinger could be my own university taking over Manchester Metropolitan’s campus in Crewe, which will allow higher education provision to continue in a disadvantaged area.

And in the same Times piece, Seldon argued that the governance of universities needed to improve dramatically, arguing that:

At least one university leader has been lost when it should have been the chairman of governors who threw in the towel. University councils should have more figures of the highest quality.

Yet by May 2020, it was Seldon that was off. Covering his resignation, The Times reported that he regarded the climate under which universities were having to operate as hostile – controversially adding Conservative generated factors like competition for student numbers and Brexit to Covid as the key contributors.

But surely every university was facing these issues? Intriguingly, the article also noted that the Charity Commission had launched an investigation into “governance and financial issues” – and one matter being looked into related to “a deal involving a campus in Crewe for the use of the university’s medical school.”

Things have gone pretty quiet since – with deadlines to file and publish accounts repeatedly missed – but now the Dec 2019 accounts reveal a little more about the Commission investigation and the Office for Students’ interventions.

Blowing the whistle

The trustees’ report says that in January 2020, the Commission wrote to the university to relay concerns that had been raised with them anonymously that related “mostly” to the joint venture around the Crewe campus, as well as a small number of other governance and management issues.

It says that the university took the concerns very seriously, and provided detailed responses based on a substantial investigation conducted by the then Chair of the Risk, Audit and Compliance Committee. It subsequently undertook a full revision of the Charter, Statutes, scheme of delegation and ordinances of the university, as well as commissioning external firms to deliver three phases of investigative work – focusing on the business conduct of several past and current senior staff officers of the university.

During the investigative work, items noted included:

- A former senior staff officer having placed themselves in a position of conflict of interest with that of the university;

- Significant and previously unidentified VAT liabilities dating back to late 2017 and early 2018 within a wholly owned subsidiary of the university;

- Insufficient engagement by the governing body as a whole in decision-making on strategic level issues.

In response to significant financial challenges, even without the impact of Covid, the report says that the university set in place a financial recovery plan in mid-2020 – major components of which were the implementation of a restructuring programme with associated redundancies; the sale of some local residential properties that were not core to the university’s activities; some renegotiated bank financing arrangements, actively seeking significant unrestricted donations (!) and, crucially, starting the process to renegotiate the agreement with the joint venture partners for the provision in Crewe:

This includes seeking a significantly lower cost for our arrangement to occupy certain buildings on the Crewe campus plus changes to the university’s share of surplus from the joint venture. Negotiations are complex but proceeding satisfactorily.

This is where things get interesting. The university has a 40% stake in the joint venture – Apollo Buckingham Health Sciences Campus Ltd (ABHSC) – which started to trade on 1 April 2019. But despite having a hefty share, it says it doesn’t have full access to the financial records of ABHSC – and while it has no reason to think otherwise, it is unable currently to confirm whether a set of unaudited financial statements filed at Companies House for the year ended 31 March 2020 are even accurate.

On the hook

Crucially, while the university has no contractual commitment to cover any losses of ABHSC, it is committed to any contractual lease payments under the joint venture agreement. It turns out that in 2018 the JV purchased the campus in Crewe, and then the university took out a ten year lease for it, under which the university is committed to payments estimated at £40.1 million in total over ten years, after the benefit of an initial £4.0 million rent-free amount.

On top of that, the university made a commitment to underwrite the rental of rooms in the Booth Hall student residences, a sublet from Manchester Met, which Buckingham is so unsure about that the accounts suggest the full amount of the financial guarantee may need to be invoked. Note 24 to the accounts tell us that a provision of over £6m has been made to reflect the discounted net present value of the potential exposure.

In a post-balance sheet event note, we are also told that a letter of claim has been received from a third party relating to the university’s financial obligations regarding the Crewe joint venture. Whilst this is a “significant financial claim of £6m”, the university has not made a provision for it as it “has sought legal advice and concludes the claim is without substance”. Let’s hope so.

To fix all of this, we are told that the university has now entered into negotiations with ABHSC, the joint venture company for the Crewe campus. The provision of allied health teaching on this campus “is growing well” but the university wishes to “review and revise” the commercial and financial arrangements as set out in the joint venture agreement, plus the university’s arrangements to occupy certain buildings on campus.

In December 2021, the university and Apollo Education UK Ltd (one of the two other joint venture partners) signed an agreement covering the intended rescission of the joint venture agreement, the intended rescission of the arrangement to occupy certain buildings, and the creation of a new memorandum of understanding as a precursor to a new joint venture agreement regarding operations at the Crewe campus. But that agreement potentially requires the university to pay sums to ABHSC and/or Apollo Education UK Ltd if the university and Apollo Education UK Ltd can’t reach agreement on a new deal.

It all, therefore, looks like quite a problem. Just as Manchester Met concluded in 2018, there’s a campus and a hall of residence in Crewe that appear to be too big (or at least too expensive) for the student numbers they’re currently generating. The problem is that Buckingham has commitments to the joint vehicle, it can’t confirm how much the JV is losing, and there are both lease payments and sub-let accommodation payments to be made or renegotiated involving Manchester Met – some of which Buckingham is on the hook for.

Add it all up, and it may cause a student thinking of enrolling on a programme in Crewe specifically or at Buckingham in general to ask some searching questions about what might happen to the university and its provision in coming years.

Going concern?

What do the auditors think? It’s taken them a while and a lot of work – total auditors’ remuneration in respect of audit services for the year ended 31 December 2019 is circa £1.5m – but a report signed in May 2022 is now there from PricewaterhouseCoopers. It says that partly as a result of the internal investigations, the university hasn’t met its obligations to file its accounts on time and is and is subject to potential regulatory action – which may include sanctions and fines.

On top of that, it notes that on its current forecasts, the university will breach its debt service covenants in the next twelve months. While it has the ability to repay its borrowings to “cure any breach” if it were to arise, it says the university has been exposed to a “number of unexpected significant one off cash outflows” in recent periods, and is currently “negotiating to lower the contracted cost of a significant lease” – factors which it says increase the level of uncertainty in the completeness of the cash outflows that are included in the forecasts:

Furthermore, in the case of the severe but plausible downside forecast, the university would not have sufficient liquidity to repay the related debt and cure a covenant breach.

So is Buckingham still a “going concern”? Under that concept it is assumed that a company will continue in operation and that there is neither the intention nor the need either to liquidate it or to cease trading. The Financial Reporting Council says that the combination of the facts and circumstances at the date of approval of the financial statements (in this case May 26, 2022) generally result in one of the three conclusions that lead to specific disclosures.

One option is to sign off on a set of accounts by agreeing that there are “no material uncertainties” related to events or conditions that may cast “significant doubt” about the ability of the company to continue as a going concern have been identified by the directors.

At the other end of seriousness, they can declare that the “going concern” basis is not appropriate as the company has “no realistic alternative but to cease trading or go into liquidation”, or the directors “intend to cease trading or place the company into liquidation”.

To be clear, neither of these extremes apply here. The middle option is that there are “material uncertainties” related to events or conditions that may cast “significant doubt” about the ability of the company to continue as a going concern have been identified by the directors, but that fundamentally the “going concern” basis remains appropriate – and that’s basically what PWC are saying here, pending resolution of the renegotiation of the ABHSC/Apollo deal, clarity on ABHSC’s finances and the disclosed legal challenge:

These conditions… indicate the existence of a material uncertainty which may cast significant doubt about the group’s and the university’s ability to continue as a going concern.

Protecting students

Given all of this, you might ask where the Office for Students has been – not least because the filing of audited accounts is one of the ways in which it keeps an eye on the finances of providers registered with it. All we know from the accounts is that in March 2022, OfS wrote to give a provisional decision that they would impose a regulatory penalty of £119,000 for the period up to September 2021 due to the late submission of financial statements:

The university was invited to make representations on this issue, giving the reasons for the delay and explaining the highly detailed investigatory work that had to be performed before the preparation and audit of the financial statements could be concluded. OfS will take our representations into account before making a final decision. Additional penalties for periods beyond September 2021 are possible.

Meanwhile, the “current” Student Protection Plan on Buckingham’s website reassures students and their families by noting that the “last” audited accounts posted with the Charity Commission (September 12, 2017 for the year ending December 31, 2016) recorded total assets of £46.18M against total liabilities of £20.87M – and so naturally,

With these figures in mind, the university believes that the risk of institutional financial failure is very low.

As per its regulatory framework, providers are theoretically required by OfS to ensure that Student Protection Plans are revised regularly to ensure that the risk assessment remains “current”. There was a time when I was worried that OfS was signing off Student Protection Plans that, in its own words, were “significantly” below the standard it would expect on the promise that providers were told to resubmit improved plans following the publication of revised guidance by OfS that never came. Then there was a period when I was worried that OfS was signing off plans that allowed a provider to “teach out” a radically stripped back version of its originally promised course by defining anything “optional” on a programme as not a “material component” to be protected. It’s an open question as to whether Buckingham would still regard its April 2018 risk assessment as “current”, and whether OfS would agree that it’s up to date and accurate.

There will be, I suspect, some that might argue that revelations of this sort or signals to prospective students that there could be problems at Buckingham are the sort of thing that might harm recruitment, make it harder for it to solve the problems that its Crewe campus is in and would therefore ultimately harm the student interest. I have some sympathy with that position.

To be fair, Buckingham thinks the risks to students are low. In a statement, it said:

The University of Buckingham is a going concern. The University of Buckingham is in a sound financial position. The financial statements just published are historical, dating back to 2019 and earlier. They reflect substantial investment in the new campus in Crewe. Financial returns after 2019 show a healthy financial position. In fact, student numbers were up 8% in September 2021 compared with the previous year which was especially pleasing given the sector was still being impacted by lockdown.

Part of the reason for the delay in submitting the return has been due to Covid and lockdowns. Also, a very thorough investigation of our financial and governance processes uncovered that there were some issues prior to the new administration taking over three years ago. These have now been fully dealt with. The University’s future continues to be secure, and it is going from strength to strength.”

Let’s hope the risks for students at Buckingham don’t crystallise, and things turn out OK in this case. But no higher education experience is risk-free. Providers can and do get into financial difficulty. The question is whether we put students and their families in a position to choose providers on the basis of the seriousness of the risk, and whether the regulator’s powers and actions protect students from those risks.

Seldon might argue that to do what Buckingham intended to do with Crewe, risk is inherent – and the state ought to provide backup in these sorts of scenarios, especially if it’s keen on “levelling up”. I have sympathy with that view – but that kind of backup isn’t being provided, and without it risks remain, as Buckingham illustrates.

Given government policy on “outcomes” is supposed to be about reducing the risk of students not getting the outcomes, where ventures like this don’t go to plan, questions will be asked about a regulatory environment that enables them to get off the ground in the first place – and why so much of the risk, in the end, seems to be on the shoulders of students, particularly from disadvantaged backgrounds or areas. As Seldon said in June 2020 when he stepped down:

Those voices who say that “lesser“ universities don’t deserve to survive Covid are ignorant of the existential importance of these very universities to the often disadvantaged communities in which they are rooted. It would be like saying we should close down schools in the bottom third of the league tables. Yet it is those schools, again disproportionately in the most deprived areas, that are often adding the most value to their students, even if their terminal results are not stellar.

In the same piece, Seldon said that while his tenure as vice chancellor had been a time of great stimulation, it had also been the biggest failure that he’d known in his career – but he “didn’t regret any of it.” Let’s hope Buckingham doesn’t.

Part of the problem is the sheer scale of the Crewe Campus: Forty acres, and it seems with an originally planned ( by MMU) enrolment target of 4,500 students. Difficult to see how a private medical school could possibly occupy such a space in a cost effective manner. Even the 800 place student village would, I would have thought, be difficult to fill, although if the accommodation charges low enough, it could have been an important resource for a medical college many of whose students, no doubt, would have been overseas. But only if the charges low enough.

Buckingham university will fail soon than later. Just a matter of time.

The university of Buckingham will fail due to their unfairness and prejudice against certain individuals. The university allowing cheating of students who they think are failing to boost their grades and performance for the university. Fake university with unethical conducts and fraudulent activities. No evidence of where the money is coming from certain individuals from Pakistan and Albania and many others which are not disclosed it is a matter of time they will be prosecuted and exposed of their crimes

Mmu struggled to keep the student accommodation at a level that ensured it wasn’t a loss 90% occupancy of the rooms. The buildings on the main campus are in need of repair and renovation after years of neglect. MMU only patched and made do on a lot of rooms and buildings. The Alsager site was a better site but its location wasn’t right for MMU so it closed then the Crewe site was closed as was several sites in Manchester.