It’s a commonplace that the University of Cambridge was founded by scholars fleeing Oxford. Today’s postcard comes from a university with a similar origin myth, albeit quite a lot less medieval.

And a lot newer too. We need to start in 1967, in May to be precise, when Dr John Paulley, an inveterate writer of letters to the times, had one published on the subject of university education. This included a call to action:

Is it not time to examine the possibility of creating at least one new university in this country on the pattern of those great private foundations in the USA, without whose stimulus and freedom of action the many excellent state universities in that country would be so much poorer?

And the call got a response. Three private conferences were held, two in 1968 and the third in early 1969, with plenty of disaffected Oxford academics attending. Preceding this latter conference was a declaration signed by 46 academics across the UK and Ireland, raising concerns about the influence of the state on university education. To quote from the Belfast Telegraph of Friday 3 January 1969:

Professor Gibson said today: ‘increasingly the universities are being told, usually very politely and often indirectly, at what rate they shall expand and in what directions, and most recently the relative emphasis that should be placed on teaching and research.’

He believed that this influence would increase and the power to exercise it, ‘because of the almost total financial dependence of the universities on the state.’

‘Furthermore I am convinced that centralised control of university education will in time weaken and perhaps destroy the international reputation of British universities,’ he added.

(Professor Gibson, by the way, was Norman J Gibson, financial economist and professor at the New University of Ulster – the local angle clearly caught the eye of the Belfast Telegraph.)

The argument was basically this: if the state pays for higher education, they will call the tune. And this is a bad thing, with deleterious effects for academic autonomy, for research and for quality and standards.

Now, to my mind this argument omits the social justice and economic benefits of expanding access to university education, but it is hard to deny the proposition that the current financially-dependent HE sector in the UK is not exactly brim-full with stable and autonomous universities.

So what happened as a result of the conferences? University College Buckingham, that’s what. It gained corporate form (as a non-profit charity) in 1973, started building works in 1974, and admitted its first students in 1976. Its first vice chancellor was Max Beloff, an Oxford professor.

Buckingham was different – its undergraduate degrees were offered over two years, not three, students started in January not September, and it sat outside the state’s funding apparatus, and outside the UCCA (the Universities’ Central Council on Admissions – along with its polytechnic counterpart, one of the precursors to UCAS). If my memory is correct, there was an external academic advisory committee, which mentored the new university college through its initial years. It gained university status in 1983, under Margaret Thatcher’s premiership. (Mrs Thatcher, as former education secretary in the 1970–74 government, and then leader of the Conservative Party, had also opened the university in 1976. It is safe to say that she was in favour of the project.)

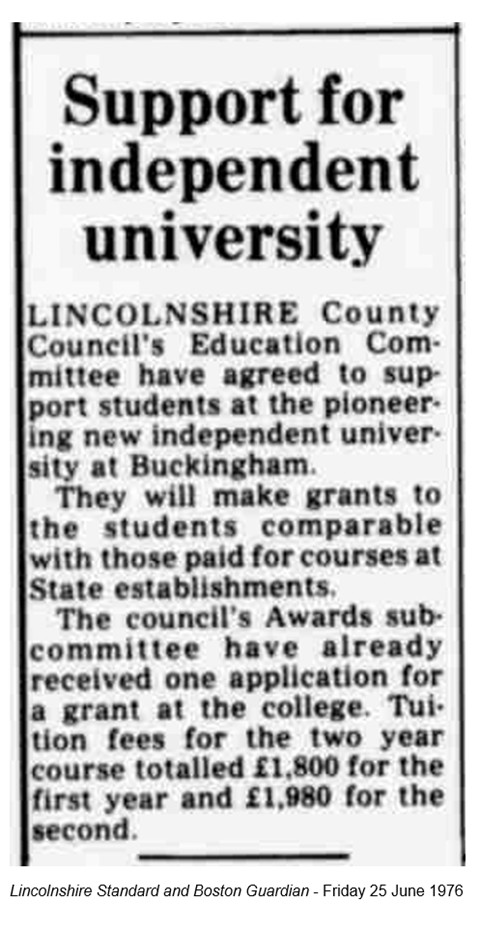

Buckingham continued its journey parallel to the mainstream university sector (albeit still with an element of state support – see the below snippet from the Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian in 1976) until 2001, when it subscribed to the QAA and joined in with the sector’s quality assurance system. From 2004 its students were able to access loan funding via the Student Loans Company, which enabled more students to attend: between 2007 and 2012 the university roughly doubled in size, although it was (and is) still relatively small.

With the coming of the Higher Education and Research Act and the establishment of the OfS in 2018, Buckingham opted to maintain a certain arm’s-length-ness from the state: it is an Approved provider, meaning that it does not get the full £9,250 fee, nor any form of grant support from the OfS; but nor are its fees capped at £9,250. Students can access fee support loans up to £6,000 (or thereabouts) but Buckingham can charge more. And it does, although total fees are comparable with a full-time fee at another English university. Overseas students pay more, but the premium looks to be less, to my eyes, than at other UK universities. So, the principal of autonomy from the state is protected, to some extent.

But only to some extent: the university still has to comply with the OfS conditions, and it became one of the first cases of a fine being issued for non-compliance: in this case, over late publication of accounts. This caused a certain amount of interest at Wonkhe towers: here in relation to the accounts when published; it’s also worth reading the OfS note on why the fine was as it was.

In 2015 the university opened the first private medical school in modern UK history, working with the Milton Keynes NHS Foundation Trust to provide clinical placements.

Buckingham’s alumni include Brandon Lewis, former Secretary of State for Northern Ireland; Pravind Jugnauth, former Mauritian Prime Minister and leader of that country’s Militant Socialist Movement; and Marc Gené, racing driver and winner of the Le Mans 24 hour race.

Before we finish, it is worth a pause for reflection on the Buckingham story. As an experiment in trying to create a university outside of the normal state apparatus it is, I would argue, an unequivocal success. It is coming up to 50 years since the first students were admitted; there must be at least 50,000 Buckingham graduates; the university has expanded into different subject areas. None of this will have been easy to achieve.

But perhaps the wider quest – to help create a private university, whose freedom of action would stimulate the other universities to innovate and improve – is at the very best a work in progress. One could point to the two-year degrees now available at some universities, as being a consequence of Buckingham. And this probably has some merit. Equally, the experiment shows that the degrees work for some specific student groups – for example, some mature students on courses with a specific professional orientation – but they’re not a panacea to all cost evils.

And maybe the quest is a chimera. The recent rows in the US about Harvard, the private university par excellence, show just how much state funding it receives. (The amount under threat is about $2 billion, which is about five per cent of the total turnover of all universities in the UK.) What I think, for what it is worth, is that the UK sector with a Buckingham is better that it would be without.

The postcard itself is not only of the university, although one of its building is shown top left, by the Great Ouse. The others are Buckingham scenes: the old gaol, the High Street, and the golden swan atop the old Town Hall.

Here’s a jigsaw of today’s card. Thanks to Harriet Dunbar-Morris, Pro Vice-Chancellor Academic and Provost of the university, and an old pal from 1994 Group days – for suggesting Buckingham. As always, if you have a request, please let me know. If I don’t have a postcard, I might enjoy tracking one down!

Appropriate choice of alumni, as it’s Le Mans this weekend.