Scraptoft Hall was built in 1713 – it is in the village of Scraptoft, which is just outside Leicester.

It has a Grade II listed boundary wall and iron gates. But before you start thinking you’ve accidentally clicked through to the National Trust website, let us remind ourselves that in 1954 the Leicester Corporation bought the hall and it became a site, for just over four decades, for higher education.

Some history will give context. The 1944 Education Act committed to all children having an education; an obvious question was who would teach the expanded school rolls. In response, emergency teacher training colleges were established, some of which went on to become universities in their own right – others of which were eventually merged with other institutions, often the local polytechnic.

Leicester City Council, being ambitious, planned a two-year training college, and in 1945 the first students were admitted to the City of Leicester Training College for Teachers. The College had no buildings – the first cohort observed classes in schools, and then studied at home. That all puts today’s Covid-caused-study-from-home into perspective.

The college found temporary accommodation, but in 1954 the council bought Scraptoft Hall as a location for the college, and in1960 it moved in. The hall contained the offices for the college – new buildings were constructed including an assembly hall, a dining hall, a library, a kitchen, teaching rooms, an arts and crafts block, a music pavilion, a gymnasium, and halls of residence.

In the 1960s the college became the City of Leicester College of Education, awarding degrees through its partnership with the University of Leicester. And in the 1970’s, prompted by a circular from the Department for Education and Sciences, the local authority’s education committee resolved that the college should merge with the then Leicester Polytechnic, as its School of Education.

Leicester Polytechnic became De Montfort University in 1992. Initially it pursued a policy of expansion, and opened additional campuses across the East Midlands. This policy was reversed in the new millennium, and the university closed its Scraptoft Campus. The house is now luxury flats, and the other campus buildings have been demolished.

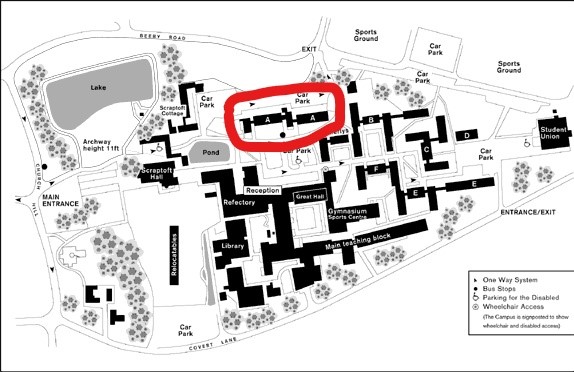

In the 1980s and 1990s the campus was home to halls of residences, and it is there that we find our special connection, in the person of David Kernohan, resident of Room 8, Thurnby Hall, which is block A, circled, on the map. Clearly this was the best block – near the lake and, very importantly, located 15 seconds from the bus stop into town. The campus also provided opportunities to learn many musical instruments, principally those left in the various practice rooms on campus.

So, if ever you have enjoyed David’s data analysis, insight and commentary on Wonkhe, join me in raising a glass to Scraptoft Hall.

Very nerdy comment here, but as a resident of Thurnby Hall in 1983/84, (possibly room 9 though I can’t recall), I feel compelled to clarify that the annotation on the map actually covers Thurnby Hall (on the left), and then, on the other side of the shared common room (in the middle), was the far inferior Bushby Hall (on the right).

Thanks, Martin – very important to get the correct understanding of Halls of Residence hierarchy!

(LSE Rosebery Hall much better than Passfield and Carr Saunders, by the way)

I was also a resident of Thurnby Hall – room 15 on the first floor for four years (1970-1974). The common room at that time was known as the TV lounge and below this on the ground floor was the college bar. The Thurnby and Bushby Hall telephones (one each) were both on the staircase in Thurnby. Phone numbers were, respectively, Thurnby 2357 and Thurnby 2364.

I was a resident of Netherleys Hall 81/82

Being an all girls hall we were often to be found in Thurnby and Bushby halls! I was at the campus till 1984. It was such a great place!

I was a staff member in the Library from 1986-1989 when I decided to enter HE as a student. I worked and was a student at the Univ of Bolton, Lancaster, Loughborough, Nottingham and Nottingham Trent. However, Scraptoft was by far the best campus. My experience was reinforced by family connection to the grounds. My grandfather and grandmother (1950s) worked in the old hall providing accommodation support and caretaking. I was christened in the church, and my mother and aunt lived onsite in a cottage by the pool bordering what must have once been the walled garden. Stories abounded of… Read more »

I lived in room 5 Thurnby, right on the corner nearest the entrance and the bus stop, during Sept 1997-July 1998. It was special being in a rural student village away from the city in that first year, and as I studied Contemporary Dance, the dance studio was but a few steps across the street from my room, I literally fell out of bed stoned from the night before and tumbled into class each morning. Better still the accommodation was catered breakfast and dinner – from the food hall opposite. I certainly miss the chocolate rice krispie cakes, they were… Read more »

I was in halls at Scraptoft for two of the three years I was at Leicester poly. Definitely the best, though id have to dispute the claims made here about which was the best hall 😉

Attended 1969- 72 Thurnby 36. PE student. Enjoyable time. Did a Post graduate course at Loughborough 1987 – 90.