One of the oft-rehearsed arguments against the pursuit of student satisfaction is the idea that it is antithetical to being stretched, challenged or even judged.

This quintessentially British idea of education as something that students have to survive rather than something they might savour runs deep – and infects everything from funding systems to assessment regs, from student housing through to “freshers week”.

It’s why arguments about improved teaching and support, or scaffolding that explains to students how they can succeed, fail to register on those concerned about grade inflation.

For them, getting their upper second from the Russell Group was both about them surviving and about them being the fittest – where all the Darwinian sorting, selection and competition serves to (re)produce and reassure the winners that come to rule over us.

Drop out in the ocean

Here’s an example. It’s never made much sense to me that while the Westminster government has seemed so keen to bear down on non-completion, it’s also been desperate to constrain grade inflation.

How on earth is being pleased with more students making it to undergraduate year two and three compatible with being upset when more students go on to get a good grade?

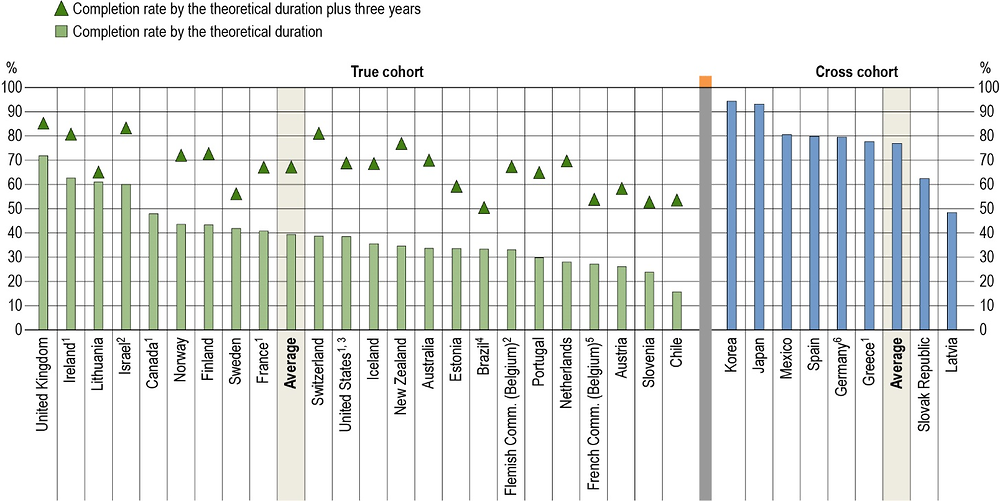

It’s also odd because, when compared to other countries, we appear to do very well on students staying the course. Over in central Europe just 30 per cent of students complete on time – while we tend to hover around three quarters of students that enter eventually booking a gown.

Over time, our completion rates are all the more remarkable for their failure to crater as the sector has expended and diversified its intake.

Almost twenty years ago the National Audit Office was asked to interrogate why “only” four out of five were graduating – with international comparisons suggesting that diversity and expansion would be the enemies of completion without careful nurturing and support.

But today, HESA tells us that 82.1 per cent of UK domiciled full-time first degree starters are projected to obtain a degree at the same provider where they started – and just 9.4 per cent were projected to leave higher education with no award – the lowest proportion since records began.

So well done everyone, and trebles all round. No complacency, and always further to go and all that – but whatever we’re doing, we’re doing it right. Or are we?

Some regrets

In 2014, the HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Survey told us that, knowing what they know now, 32 per cent of students would have not have chosen the course they were on.

By last year an equivalent figure appeared to have risen to over 40 per cent – with Black Asian and Minority Ethnic students, and those from poorer backgrounds, hovering at around half expressing regret.

Comparing all of that to a system like, say, the Netherlands is revealing. For a start, once we add three years to the theoretical duration of the programme, its 40 per cent completion rates rise to over 70. Why are we in such a rush?

It’s also the case that Dutch students who withdraw before February 1st get much of their student debt wiped, “Binding Study Advice” at the end of the first year is designed to determine if a course is really right for the student, and those who transfer to other institutions (“omzwaaiers”) aren’t generally picked up in the numbers.

And resultant “wouldn’t make the same choices again” score? Fourteen percent in last year’s Netherlands NSS.

That our system enrols and then traps students onto programmes that they are unhappy on, requiring them to complete those programmes at a pace incompatible with their diversity or adversity, is a possible explanation.

That that, when coupled with a lifetime of additional tax payments framed as debt that is almost impossible to pay off, will almost certainly have profoundly negative implications for their personal commitment to lifelong learning and their political commitment to investment in education, is a potentially pernicious long term problem.

That it all means that we ought to pay much more attention to overall levels of regret, and differential levels of that regret by student characteristic, subject and provider, hopefully goes without saying.

And redoubling our efforts to reject the “in at the deep end” framing of freshers – when those from identical social backgrounds in small residential groups were never really in at the “deep end” anyway – becomes an essential task for anyone interested in the student experience.

Belonging again

In a paper for that National Audit Office work, there’s a fascinating summary of the work of the Netherlands’ Expertise Centre for Diversity Policy – which by 2003 had already undertaken extensive quantitative and qualitative research on both the access and participation of students from Black and Minority Ethnic backgrounds.

In the findings, student associations “appeared to be the best means of bridging the gap” between isolated ethnic minority students – having a “positive impact” on student retention.

Academic integration was important – introductory programmes familiarising students with the degree course seemed effective.

Having accessible staff who created an environment in which “a student feels part of the course and is challenged”, was also seen as a major positive factor in increasing student motivation.

Bring it all together, and in later work the key to reducing differences in study success between student characteristics was summarised as “learning communities” where “small scale” was “consistently implemented”.

Small groups, short projects, associative activity, rotated student involvement with each other and staff, and opening out only when all students were ready – leading later to more independent and autonomous study.

Because guess what:

…in a learning environment where students are expected from the outset to adopt an independent attitude and find their own way, indigenous students seem to thrive better than non-Western students. Students from the first group may know better what is expected of them, they will be able to integrate more quickly into the educational regime at the degree program and, partly as a result, achieve better study results.”

In other words, it’s possible, and perhaps even tempting, to improve non-continuation or even success rates by assuming that the “shallow end” is about things being easy.

But making academic activity itself less challenging, while leaving the environment around it hard to navigate might be misreading what a necessary “shallow end” is – and it may well be that swapping around those assumptions is what leads to happier and more successful students.

And more fundamentally, it’s starting to become clear that while European HE has massified along with the UK, the idea of retaining the “small” in that massified system has come to be regarded as disproportionately important to transition, satisfaction and attainment.

Who’s on the bus?

On the study tours we’ve taken SUs on in recent years – to regions as varied as the Scandinavian countries, the Baltics and the Low Countries – one of the underpinning (and often hidden) commonalities were the way in which students were inducted and student communities were constructed.

On the surface, there were plenty of deep ends to be found – large group lectures on dos and don’ts, big parties, intimidating campuses and student bodies in multiple cities of 50, 60 even 70,000 students. But something else was going on too.

Almost everywhere we went, for example, subject and programme associations were as important as central students’ unions. Students were consistently more enthusiastic about collaboration and group work. Committees and boards trumped heads, presidents, leaders and others we can blame. Spaces were cosier.

It’s not that getting new students into “family groups” of between 5 and 15 students, to be mentored by more experienced students, is something that can’t be found from time to time in the odd medical school or international office in the UK.

It’s that the scale and ambition of those programmes right across the countries we’ve seen – almost always led by students’ associations whose concerns include both social and academic integration – puts what is done in the UK to shame.

This programme at VU Amsterdam, for example, is utterly typical. Students are divided into a group with around sixteen fellow students and two experienced mentors. They can choose between “going all in”, including an evening programme over five days or participating in a shorter programme over two days.

Mentors are trained to meet with their group and plan activity that causes students to

- Become acquainted with their degree programme and fellow students;

- Be familiar with the campus and the city;

- Participate in activities performances staged by other students;

- Participate in workshops that help students prepare for their studies;

- Understand more about the associations and activities on offer in the city.

And on that belonging thing? “You will no longer feel awkward: when you walk into the lecture hall a few weeks later, you already know everyone.” There are versions for master’s students, adaptions for international students, and even a parallel programme led by students for students who are first in the family.

At Roskilde in Denmark, each mentor looks after 3-5 new students both before and throughout the first semester. In Lithuania students were enrolling onto summer camps to take part in teambuilding in small groups. In Germany we saw subject-based students’ associations running welcome and orientation events designed to cause intercultural exchange and reflection, and in Sweden academic societies were staging folksy freshers weeks like this – without a wristband for a nightclub in sight.

At Lulea University in Sweden, one of the four purposes of the two week introduction period is to create community in the subject area. At Aarhus University in Denmark, Kulturkammerater involves students from the city (often commuter students) leading groups of new students to explore a cultural site or a leisure activity. Another project matches new international PhD students with families from a network of local businesses.

At Jonkoping University in Sweden, Food Safari is like a pub crawl without the alcohol that allows students to meet (and eat) with those from other countries, and at Aalto in Finland academic organise their own “head start” events where new students get to meet each other.

You would say that

As someone who’s spent a lifetime woking in and around students’ unions, you’d expect me to be particularly interested in the way in which we can support students to support others.

But the point isn’t that the only thing that every university should do is ensure that their SU is developing its academic societies and organising an ambitious family-based mentoring scheme – although that would help (and there’s endless academic research that bears that out).

It’s about a recognition – in an age where we know that students need to bond before they bridge – that that is easier to do in a group of six than in a lecture hall (or a Zoom call) of 500.

It’s about finding ways to make small happen – in groups, teams, encounters, projects, and orientation – rather than hoping that throwing people into the massive will result in anything other than isolation.

It’s about acknowledging that mass participation and the complexities of corporate governance cause a drift to centralisation and the professionalisation of programmes – when it’s communities, collegiality, reciprocity and informality that make us feel better.

It’s about noticing that the number one issue in the youth mental health crisis is anxiety, and recalling that “feeling part of a community of staff and students” is a demonstrably good predictor of academic confidence and high levels of wellbeing.

And for all of us that survived and thrived as students in higher education earlier in our lives, it’s about remembering that we almost certainly did so in contexts that were less intimidating, less overwhelming and well just smaller than they are today.

Contexts that, given we’re all still here, are likely to have have enabled us to be remarkably satisfied with being stretched, challenged and judged.