The results of the latest student polling from Youthsight out this month showed that the Green Party’s support amongst students is holding up, perhaps increasing, as we near the election. This may well impact on Labour’s chances at the election. What is the cause of the swing to the Greens? And can Labour do anything to win students back?

The recent HEPI report Do students swing elections? hypothesised that the student vote changed according to tuition fee policies at elections. With the reactivation of the fees debate, perhaps a well-timed push from Labour on tuition fee cuts could change opinion. But do tuition fees really have such a noticeable effect on student voting behaviour?

Students do tend to give a higher priority to educational issues at general elections compared to the rest of the public. The British Election Study data shows that in 2001, ‘educational standards’ was the second most important issue at the General Election for students, the NHS being the first. In 2005, education (11%) was in the top three priority issues for students, along with Iraq (11%) and the NHS (12%).

However, it is a rather big leap of faith to suggest that one single education policy – tuition fees – could cause a huge shift in the student vote. Single issues rarely act as an electoral silver bullet, and when we get into the granularity of particular policies, the effect is even smaller.

Normally a single issue gains salience if it is used as a nodal point to help hold together a political party’s electoral discourse, as the budget deficit came to be in 2010 for the Conservatives, or as Europe/immigration could be for UKIP.

The HEPI report claimed that tuition fees policy could swing the student vote, but there was no direct empirical evidence in the report to show that the fees issue was salient enough amongst students to override other key factors in voting behaviour. It is highly unlikely that fees would be a significant predictor of the student vote in a fully specified empirical model which contained other key election issues.

Tuition fees policy also contains none of the traits of a ‘nodal point’ – it is too specific to be hollowed out as a signifier for the disaggregated demands of a larger political project.

If tuition fees were a key player in student voting behaviour in 2010, you would have expected to see two things happen:

First, there should have been a disproportionate increase in Lib Dem support during the period that Lib Dems were signing the pledge. Youthsight polling shows that there was no such increase, and that, if anything, Lib Dem support was falling slightly among students, until the TV debates and “Cleggmania” lifted Lib Dem support across the board.

Second, you would have expected to see a disproportionate fall in Lib Dem support in the student population after the vote raising the tuition fee cap to £9,000 per year. However, there was no direct correlation – students, along with many other groups, abandoned the Lib Dems when they realised they were entering a ‘pro-austerity’ government with the Conservatives. After the November 2010 student protests, Lib Dem support amongst students then fell at a similar rate to their national support.

But there is an alternative hypothesis about the difference between the student vote and the rest of the electorate.

The British Electoral Studies data shows that students tend, on average, to be more libertarian than the wider electorate and seem to take a considerably more liberal stance on a number of key social issues compared to the general public, such as equal opportunities, LGBT rights, immigration, capital punishment, and censorship.

For this reason, students may well be more likely to choose a party that they perceive to be closer to them on the libertarian-authoritarian axis.

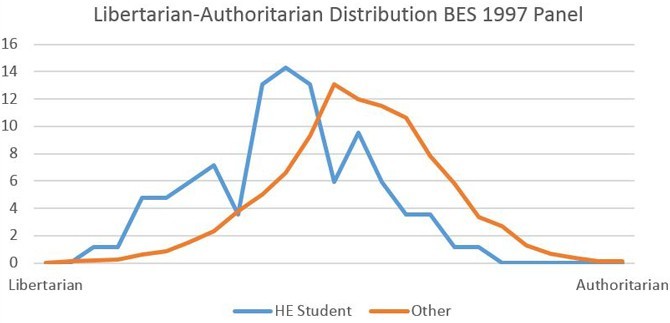

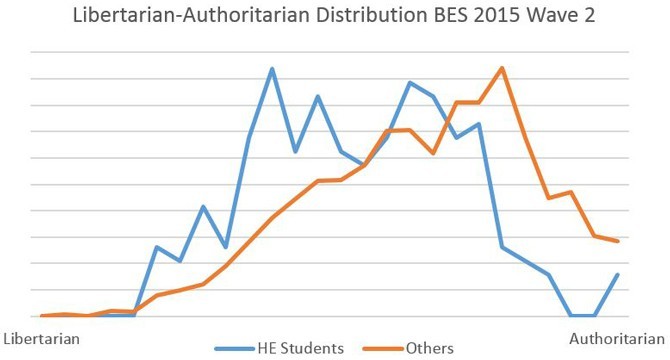

We can compare the average position of HE students to the general public on a liberal-authoritarian scale. A scale was created in the 1997 BES data, and when you separate HE students, you see a clear and significant difference between their position and that of the general public.

The latest BES survey used statements that could also be indexed into a similar scale, but as some of the statements are different, the results aren’t directly comparable. Nevertheless, we find that students are still significantly more libertarian than the rest of the public, who are, in contrast, quite (worryingly) authoritarian.

While age certainly plays a factor in these differences, being a university student seems to remain a significant predictor of liberal-authoritarian positioning even after age and other factors are controlled for.

This hypothesis does fit to a certain extent with recent student voting behaviour. Prior to 2010, the Lib Dems stood out as a socially liberal party. They opposed the Iraq War, opposed ID cards, were seen as largely pro-Europe and pro-immigration, and were outspoken on equal opportunities and minority rights.

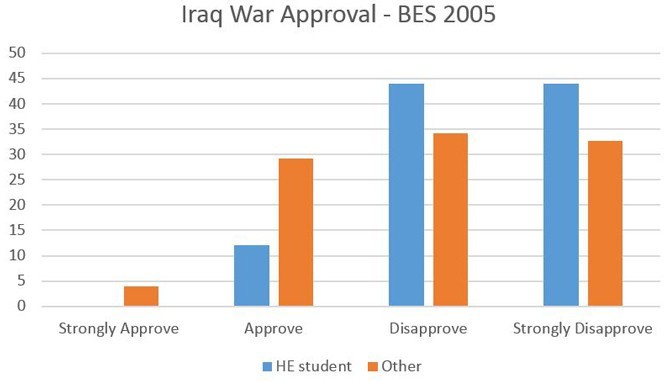

But there’s a problem with this argument. According to the HEPI report, students were “marginally more, not less, likely to approve of the [Iraq] war than the rest of the population”. I believe this finding is not only counter-intuitive, it’s also false. [See clarification below] In the BES 2005 pre-election face-to-face survey, when asked whether they approved or disapproved of the Iraq War, student voters in 2005 were statistically more likely to say they disapproved of the war than the rest of the public (by 88% to 67%). Iraq was also as frequently cited as education by students as their most important election issue.

The shift to the Greens does perhaps make sense in this wider context. It’s certainly not because the Greens have any decipherable policies on tuition fees (I doubt many students have read David Kernohan’s recent analysis of Green HE policy). With the Lib Dems tainted by their time in government with the Conservatives, liberally-minded students no longer trust them as a supporter of liberal values. Labour’s past, as well as their current approach to welfare and immigration, does not make them appear particularly liberal either.

Austerity may also be playing its part. Students will struggle to make a Syriza out of the Greens, but it may be that they are searching for an anti-austerity party. Their precarious and uncertain position in the labour market and the cost-of-living impact on housing and transport costs may be fuelling a greater desire for anti-austerity policies, but this remains to be tested.

For now, Labour’s hope for winning student voters may be to construct a more liberal party image, dropping the strong rhetoric on welfare and immigration, and place equal opportunities and minority rights higher up on the agenda. If this is articulated alongside the cost-of-living agenda, it could have a big impact. A coherent policy on tuition fees would then be the icing on the cake.

Clarification 24th February 2015:

The HEPI analysis of the Iraq issue is based on the BES 2005 internet survey with post-election responses, whereas my own figures are from the BES 2005 pre-election face-to-face survey. I did not make this clear in the article, and do not wish people to think that I am saying the HEPI figures were incorrect – the internet survey data does strangely give the result they suggest.

However, my point was to challenge, using BES 2005, the assumption that students were more approving of the Iraq War than non-students when they made their party choice at the election. I therefore used pre-election data to better capture the effect of the Iraq issue on the student vote, rather than assume that post-election opinion reflected opinion when deciding who to vote for. This methodological decision meant a smaller sample of students (N=66), and as with any small sample, some caution should be applied to the results. But I believe the clear difference in results of pre-election opinion on Iraq challenges the assumption that students were less disapproving of the Iraq War than non-students when they were deciding which way to vote in the 2005 general election.