Panic! Panic! New students are “unprepared for university”, is the BBC headline from a new report from HEPI and Unite Students, tellingly titled ‘Reality Check’. It’s up to the reader to decide whether this reality check is for students, or really for universities and schools.

This is the first major survey of applicants’ expectations of higher education prior to applying. Unite has followed up the applicants surveyed with questions about their actual student experience, the full results of which are due to be released in October. Quite why the sector’s collective wonk-research complex has taken so long to get around to this perhaps begs some questions.

In a market system, built around the pillars of tuition fees and student feedback, expectations of universities matter more than ever. That expectations, on the whole, far exceed experience, is surely not a surprise to anyone. The real point of interest is when the posthoc explanations (or blaming) start kicking in: from universities, schools, and commentators.

The results

HEPI and Unite surveyed over 2,000 young people in April 2017 applying for higher education and intending to take up a place in the next two years.

When it comes to teaching and learning, the general expectation of applicants appears to be ‘more (than school), of everything’. Nearly all applicants (95%) assume that they will do more independent work at university than at school. 66% expect more group work, and 60% expect to spend more time in lectures than in their school classroom. Such expectations are clearly not met: only 19% say they get more time in lectures than they did in classrooms once they actually get to university.

Applicants’ confidence about finding a job also appears to take a dent once they arrive at university. 66% of applicants are confident of doing so, compared to only 54% of students.

As Nick Hillman pointed out in his remarks at yesterday’s launch event, this survey is set against the UK’s atypical ‘boarding schools model’ of higher education. Only 15% of applicants expect to continue to live with their parents or guardian while at university. British students are completely uprooted from their academic, financial, residential and social habits when they go to university. They are starting a completely new life.

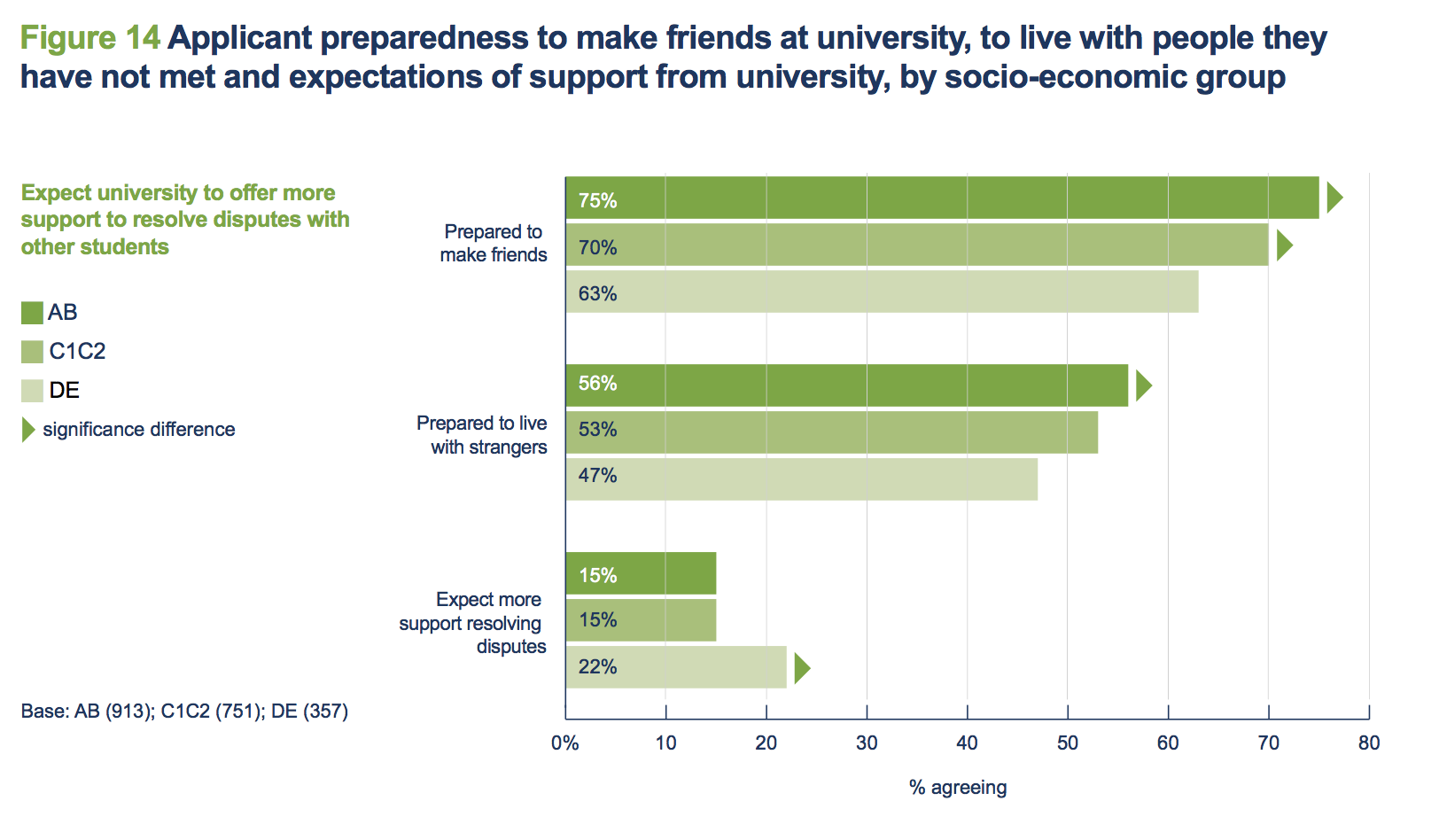

That such a system might confer some unfair advantages to the more socially confident and advantaged is underlined by the survey results. Applicants’ preparedness (read, confidence) about social success varies significantly by social class.

Source: HEPI/Unite

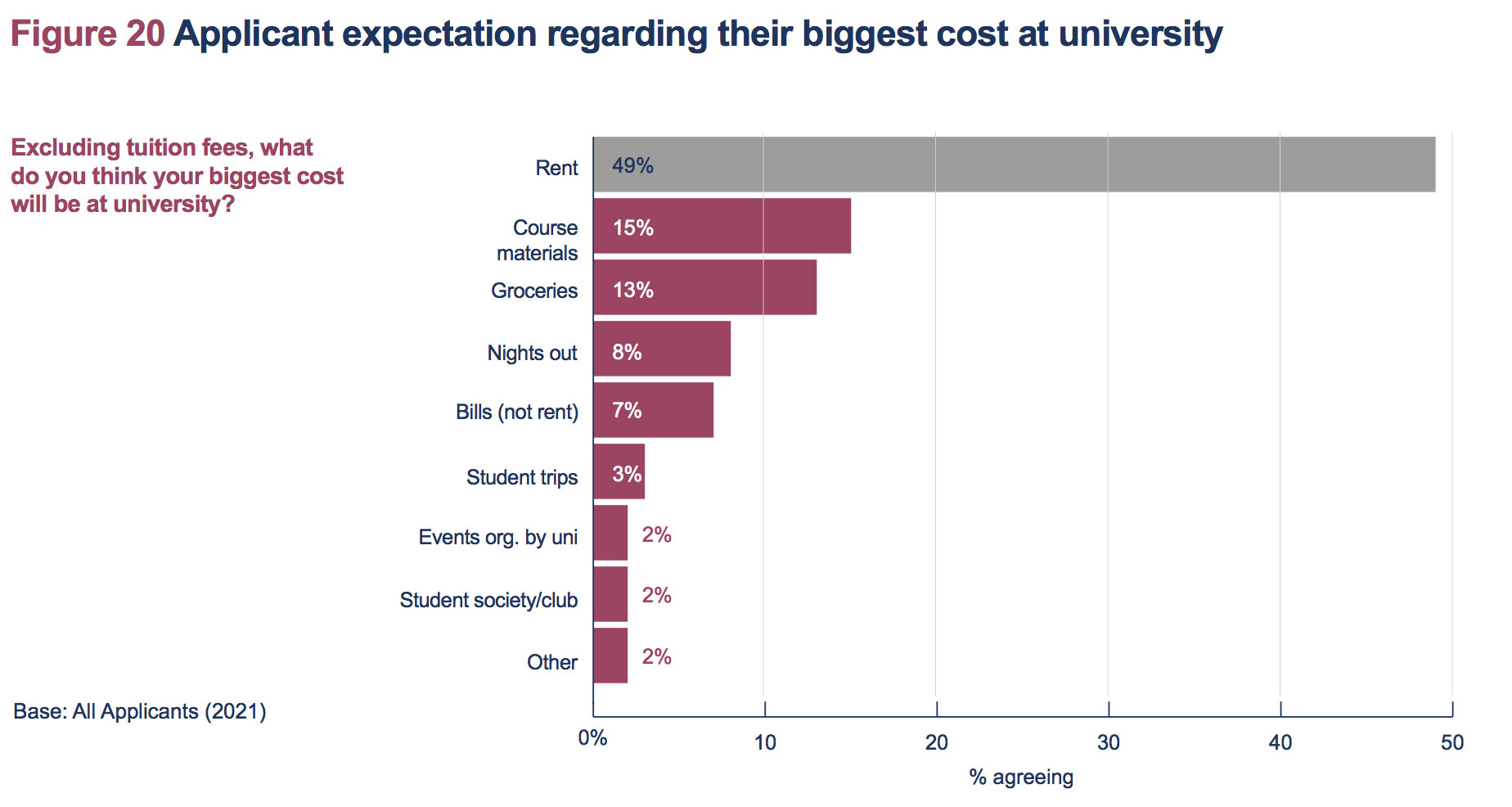

With the debate about higher education funding reignited by Labour in the General Election campaign and now by nervous Conservative cabinet ministers in its aftermath, new insight about applicants’ expectations of costs and maintenance support are timely. Rent is by far the biggest expected cost, but it’s more concerning that over 50% of applicants don’t believe rent will be their biggest cost.

Source: HEPI/Unite

It’s a shame that the survey question excluded tuition fees, as its inclusion might give us an insight into applicants’ level of understanding of the loans system – that while studying they will not pay a penny towards their tuition. Indeed, given the public debates over the last week, my main recommendation for future iterations of this survey would be to gauge the extent to which applicants actually understand how student loans work, and how this might affect their decision making, hopes, and anxieties.

Across a range of topics picked out by the survey, there is an interesting alignment of expectations for pastoral support. The most frequently expected sources of support are (unsurprisingly) family and friends, but 39% of applicants expect support from their university on finances. 50% feel likely to seek support from lecturers and tutors if they ran into difficulties, and 47% from a university counselling service. And 78% expect more career-planning support at university than at school.

The blame game

The challenge for universities is that market pressures are incentivising them to both inflate and also manage expectations. Responsibility for both usually lies in separate departments: the marketing team, and the teaching and support staff respectively. As Anne-Marie Canning, Director of Widening Participation at King’s College, London, stated at the launch event, universities are too often selling applicants a “best case scenario”. If experiences fall foul of these high expectations, universities can find themselves in trouble.

Naturally, one response to be heard from the sector is to complain that schools are doing an insufficient job in preparing for university. Given that we still have (at least nominally) a selective entry system to higher education, with proudly autonomous institutions able to set their own terms of entry, this feels a little churlish. Chris Ramsey, Headmaster of The King’s School, Chester, pointed out that what were once ‘School Liaison Officers’ at universities have now become marketers. This has implicitly undermined the reliability and information that applicants are receiving about higher education in-the-round, as opposed to merits of any one particular institution. “It’d be wonderful if universities were more confident to talk about what they don’t do”.

Complaints about lack of ‘preparedness’ also smack of social class elitism. Sonette Schwartz, Principal of Brockhill Park Performing Arts College, a secondary school just outside Folkestone, noted that in her experience students with the highest expectations are typically those from the least advantaged backgrounds. Schools, for their part, are wising to the growing mental health challenges of young people, and beginning to teach resilience to their pupils. “It’s very easy to blame the predecessor institutions”, says Schwartz, “but we all have work to do here”.

This seems particularly appropriate when it comes to changing approaches to teaching and learning. I’ve written before about how the sector continues to misunderstand student complaints and expectations about contact hours, and how the sector’s defensiveness on this topic will do it few favours. The HEPI-Unite survey focuses very much on applicants’ expectations of different teaching ‘outputs’, such as lectures, tutorials, and group work, but perhaps what we really need to understand applicants’ hopes for their learning and development. Perhaps that might be too difficult to articulate. But finding an alignment between students’ hopes for themselves and their educators’ expectations of them is at the heart of learning. The new market system has created huge challenges in this space, as the survey results show.

As one attendee put it at yesterday’s event: “Universities are selling a dream to applicants, and then have to bring this dream back to reality for students”.

I have been undertaking entry to study surveys at UG and PG level looking at prior learning experiences and expectations on up-coming university study for over 15 years across a number of universities. The last project I created and led where this was undertaken was the Postgraduate Experience Project (PEP) undertaken across 11 UK universities. http://www.postgradexperience.org/ The findings in the HEPI/Unite study aren’t a surprise and it is a welcome report bringing debate on this area finally to the fore. The undergraduate student body has changed in terms of expectations and engagement across all levels of study so applying our… Read more »

tag:twitter.com,2013:885864050109841408_favorited_by_183595137

Drea Teran

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885864050109841408#favorited-by-183595137

tag:twitter.com,2013:885864050109841408_favorited_by_18585906

Idlan Zakaria

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885864050109841408#favorited-by-18585906

tag:twitter.com,2013:885864050109841408_favorited_by_297670835

Ruth Arnold

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885864050109841408#favorited-by-297670835

tag:twitter.com,2013:885864050109841408_favorited_by_472342745

Ursula Kelly

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885864050109841408#favorited-by-472342745

tag:twitter.com,2013:885864050109841408_favorited_by_14585019

Robyn Bateman

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885864050109841408#favorited-by-14585019

tag:twitter.com,2013:885068826228006912_favorited_by_297670835

Ruth Arnold

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885068826228006912#favorited-by-297670835

tag:twitter.com,2013:885864050109841408_favorited_by_18772681

luweasel

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885864050109841408#favorited-by-18772681

Applicants’ expectations of universities are very different to their experience, but whose fault is it, if any? ow.ly/Icys30dCGfy http

tag:twitter.com,2013:885864050109841408_favorited_by_3091115111

James D. E. Cross

https://twitter.com/Wonkhe/status/885864050109841408#favorited-by-3091115111

Applicants’ expectations of universities are very different to their experience, but whose fault is it, if any? ow.ly/Icys30dCGfy http

Expectation mis-management – what do applicants think about going to university? ow.ly/ZYgD30dosRx

Expectation mis-management – what do applicants think about going to university? ow.ly/ZYgD30dosRx

Expectation mis-management – what do applicants think about going to university? ow.ly/ZYgD30dosRx