“Last year, I sort of like fell through the net, just because I had circumstances that they didn’t really notice. Like, I stopped showing up. Nobody noticed. My friend as well: similar circumstances, she stopped showing up, she stopped submitting assignments, nobody noticed.

There’s a lot to unpack in that focus group quote from the UPP Foundation’s terrific and yet disturbing Student Futures 2 report. When the (21 year old, female, psychology, research intensive university, home) student says that “nobody” noticed, does she mean nobody employed by the university, or nobody at all?

Given she mentions her “friend”, the natural thing to do is to assume the former – and to assume that either smaller class sizes or learner analytics might solve the problem. But is it even a problem? Isn’t the “growing up” bit of university all about it not being like school where someone would check up on you? When I was a student…

We can go round in circles forever on questions like that – I certainly have done ever since I started tracking (and sometimes commissioning) research on community and loneliness back in 2019 – but what’s clear is how important feeling part of things is to students across the board.

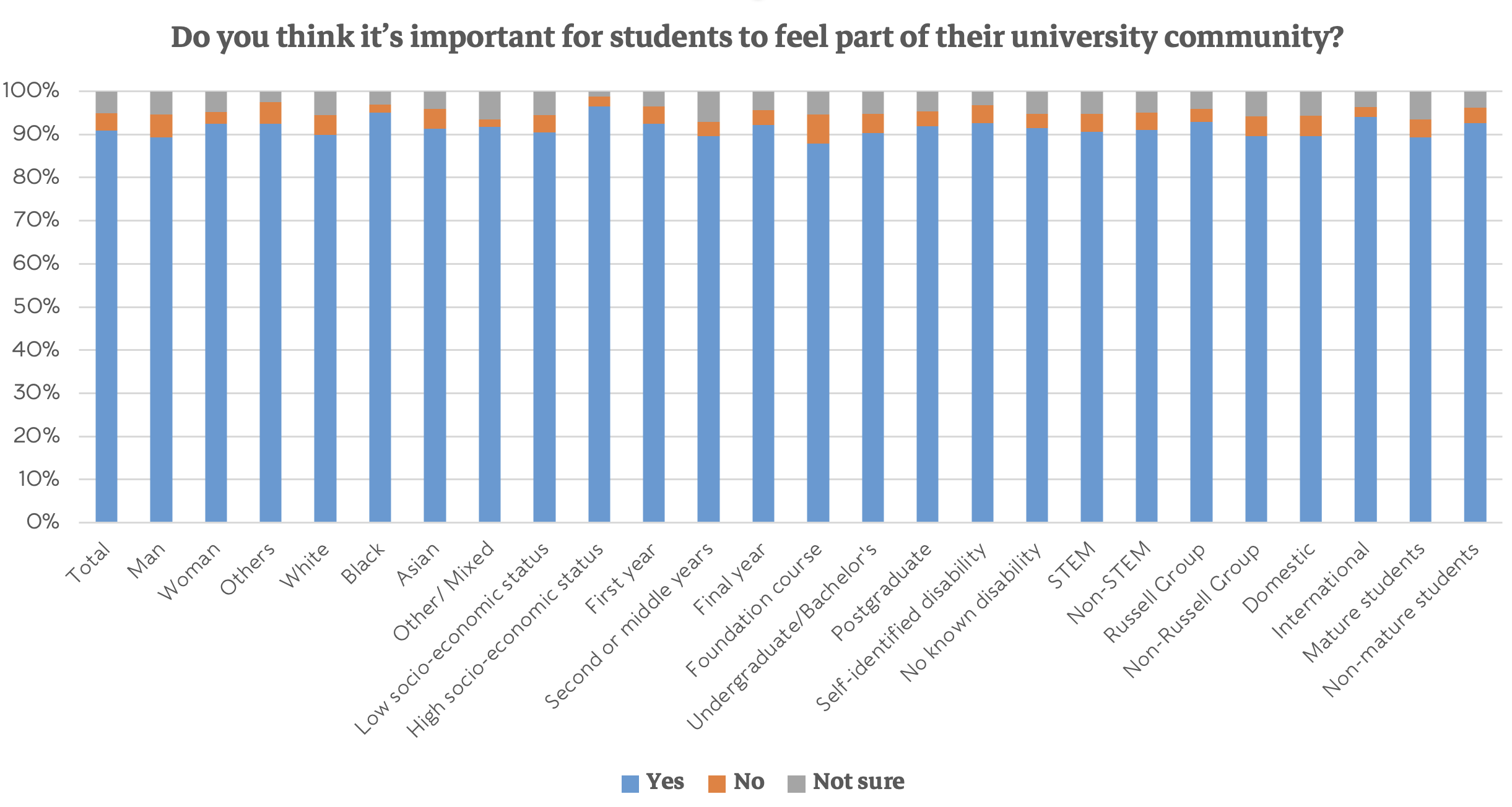

In the polling accompanying the report (carried out by our friends at Group GTI/Cibyl), there’s a remarkable consistency in the extent to which students think it’s important for students to feel part of their university community:

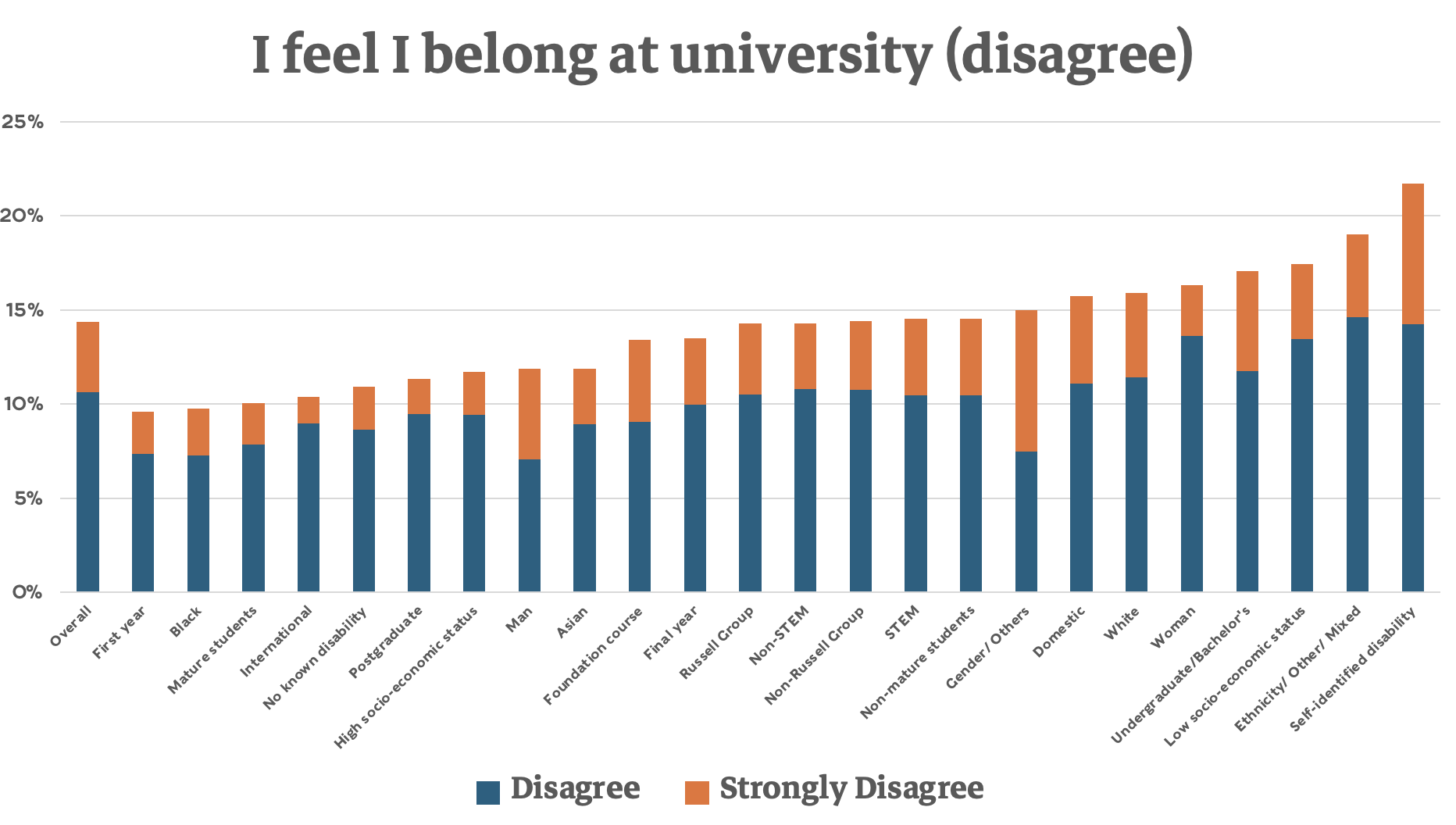

…and a remarkable inconsistency in the extent to which they actually feel they belong. Here’s who disagrees that they do on a five point Likert scale:

One of the things that I find fascinating about that chart – versions of which pop up in other research on belonging – is the way that upends lots of assumptions among those I talk to about the issue.

There are all sorts of people that work at universities where eggs are placed in belonging baskets to focus on first years, Black students, mature students and international students – and maybe charts like the above show off the fruits of that labour.

But one characteristic where both the proportion sharing it is growing – and the proportion of them appear to be lonelier than ever – is on the right hand side.

Disabled students

If we dig into the data and compare scores for Disabled and non-Disabled, a grim yet now increasingly familiar picture emerges.

Disabled students are just as likely to agree that feeling part of the community is important – but much less likely to feel they belong, more likely to be lonely, less likely to be happy in higher education and and more likely to say that going to university has made their mental health worse.

Similarly, while comfort in accessing university support services is broadly comparable between the two, confidence that those services would help is much worse amongst Disabled students. They are also less likely to agree that their university has given them the support they need to prepare for the start of term, more likely to call for induction to last longer than freshers week, and more likely to want transition support between academic years.

There are important differences in the activities that make students feel more part of the university community too. Disabled students are much more likely to identify both pastoral support and mental health support as things that would help – but they are also more likely to say that social/informal activities with other students, SU activities and mentoring and/or support from other students would help too.

Yet they’re less likely to have engaged in extra curricular activities, and while having the time to do so is just as big a factor as it is for their non-Disabled peers, and while their interest levels are identical, the stand-out difference is anxiety – with 35 per cent identifying it as a reason for non-participation, as opposed to a quarter of their non-Disabled peers.

Anxiety rules

The rise both in the volumes and proportion of students enrolling into higher education with specific learning difficulties, social/communication impairments and mental health conditions is well understood – as is the link between those factors and anxiety.

We also know that anxiety is on the rise – and having seen a dramatic uptick during the pandemic, is the one mental health factor of the four classic questions amongst students that seemingly persistently refuses to come back down.

We perhaps know less about the volumes and proportion of students who become, or at least realise that they have, these conditions while at university – although we do know that the difficulties in “proving” that those conditions have a substantial and long-term adverse effect underpin many of the debates surrounding “duty of care” and high-profile student suicide cases.

What’s interesting to me is the extent to which support for Disabled students remains something that is so focussed on individual diagnosis and support.

We know the drill. If the student has the label, they get a support plan that students struggle to have followed. Because getting that label is both onerous and othering, many don’t try – and where they succeed, they face a barrage of barriers that raises eyebrows at the adjustments agreed on the basis of academic excellence, fairness, and anyway – you won’t get treatment like this in the “real world”. And we certainly rarely place expectations on or offer support to students that aren’t Disabled to support those that are – despite many feeling keen and desperate to do so.

Underpinning all of that is an ongoing assumption in some quarters – that at least some of those with specific learning difficulties, social/communication impairments and mental health conditions represents some sort of over-diagnosis, a social phenomenon which has converted acceptance and understanding into medicalising a self-pitying self of entitlement at best, and outright cheating at worst.

When it comes to teaching and learning, we might hope that the high-profile cases trigger a fresh look at the difference between competence standards and assessment methods – albeit that at the edge of those discussions there remains a lingering concern that even if “presenting to a room full of people” isn’t a necessary competence for a physicist, those presentation skills probably remain in the graduate attribute frameworks that float around what the sector says it inculcates in its outputs. We might also hope for a renewed focus on mental health in the competence standards of teachers, too.

But on all of this, what I’m most struck by is the comments that stuck out for me in the qualitative feedback I was buried in back in some of the early polling we did on loneliness in 2019. Asked why students hadn’t got involved in what we might variously call “university life”, cost, time, and information were all in there – but the thing that came up again and again in the answers, especially amongst those with high anxiety, was dead simple – “I didn’t have anyone to go with”.

The immersion puzzle

The combination of a more diverse student body on campus, and less time (and academic need) to immerse in that campus “experience”, is in many ways emerging as the ultimate puzzle for policy-makers when it comes to the higher education student experience.

Demand, expect and normalise the immersion of the past, and you shut out tens of thousands of talented students who can’t get there. Adjust, shift and bridge, and you make it possible to pass – just less possible to do so with the social capital dividend that higher education is supposed to offer.

Much of that then falls into the usual “but is it our fault” debates that forever plague access and participation – and it’s true that there’s only so much that universities can do about maintenance loans, rising rents and public transport problems, just as there are limits to what can be expected of universities when Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services are in a spiralling, never-ending, freefalling crisis that’s now bringing down local authorities too.

But universities do have duties over Disability – and as well as the requirement to make adjustments for individual students that are reasonable, the duty to do so in an anticipatory way is also front and centre in the Equality Act 2010. And yet I doubt that when it comes to the social aspect of university – which we increasingly know is central to the success aspects both while there and on exit – that there’s many universities that could, hand on heart, say that they have a strategy for belonging that is truly Disabled-friendly.

Universal design

I’m not the first to have argued that the way in which the rise in diagnosis of specific learning difficulties, social/communication impairments and mental health conditions ought to be causing much more a shift in general teaching, learning and assessment practice – universal design for learning concepts still feel like an enthusiasts’ hobby in many universities, where enrolment data by subject and the commonality of adjustment design in support plans should mean much more of a focus.

But in truth, while the boundaries between the two are pretty porous (hence the hair-pulling conversations between Disability departments and academic departments setting group work), the wider student life and social aspects of those disabilities get much less focus.

Some of that is about the EHRC’s insistence that anything organised under the auspices of a students’ union isn’t covered under the educational duties that either the state or the university has – with the resultant gap in support between the film screening organised by the module leader and the film screening organised by the academic society getting wider and wider.

Some of it is about all of those attitudes about normality, demand, possibility and responsibility that give us comfort when the stats show up as they do here. Some of it really is about capacity and funding – and the sheer lack of it that’s around these days to even attempt to make headway on something that feels so hard to grip.

But as ever in HE, I suspect that at least some of it is about both the role of Disabled students collectively, and the role of non-Disabled students too in making whatever higher education is like these days a more equal sort of environment to access.

On our study tours, over in Finland – with its consistently higher staff-student ratio than on offer in the UK – the national student tutoring materials suggest that each and every new student that enrols is introduced to navigating other students’ diversity carefully upon enrolment. In Ireland (where the SSR is approx 30:1) in late February too, listening to those organising similar schemes, it’s hard to avoid the sense that students who are supported to understand and look out for other students feel less lonely and have more agency over their and their fellow students’ experience too.

These sorts of approaches – social/group based in nature, student-led (usually via the SU) and capable of covering all sorts of aspects of student life complexity, are neither especially expensive nor notably hard to recruit to, even as the challenges of time, cost and opportunity mount up. But they do help students overcome anxiety, they do help students understand each other, and they do mean that students have “someone to go with”.

Yes, they mean being more deliberate about students’ social lives than we had to be in the past. But what they also represent is a pressing need and golden opportunity – for universities and their SUs to build the capacity of and meet the desire of their student community to help each other to both survive and thrive through higher education. They just need to know how.

We’ll be discussing many of these issues at the Secret Life of Students in London on March 12th – tickets and information can be found elsewhere on the site.

My son is neurodiverse and has just pulled out of uni after 2 and half years. Completely isolated due to anxiety. He has had lots of support from a mentor but still havin no one to go with ìs the reason he has not integrated into student life.

Very interesting data! “Yet they’re less likely to have engaged in extra curricular activities, and while having the time to do so is just as big a factor as it is for their non-Disabled peers, and while their interest levels are identical, the stand-out difference is anxiety” Was the accessibility of extracurricular activities measured as a factor behind not engaging? Many disabled students are unable to participate because of socials, sports etc. not being set up in accessible ways.