Michael Barber’s influence on the Higher Education and Research Bill, and universities more generally, already extends far beyond his new role as Chair of the Office for Students.

Targets, metrics, reform, choice, competition, transparency, managerialism. All are contested concepts in higher education, and are frequently the topic of debate.

Yet the man perhaps most responsible for the infiltration of these ideas into the running of universities and the education sector as a whole only began a formal regulatory role in higher education this past weekend. Sir Michael Barber may have only just started his new part-time job as Chair of the Office for Students, the new all-powerful higher education regulator in England due to replace HEFCE next year. But his influence over British education policy, and indeed the entirety of Whitehall, has loomed large for nearly two decades, particularly since he founded the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit under Tony Blair in 2001.

Barber’s appointment as OfS chair was a good reason to finally open up his 2015 book, long on my reading list, entitled How to Run a Government. With all the authority that a Penguin orange spine confers, Barber has clearly thought long and hard about many of the common problems that anyone working in public policy must face up to. How can governments convince sceptical taxpayers that their money is being well spent? How can the public sector, without a natural market incentive, improve its efficiency and efficacy? How is one supposed to deliver the often wildly optimistic promises made by politicians?

Fundamentally, how can still-monolithic-yet-modern states maintain the trust of their citizens and service users?

Part guidebook, part academic criticism, and part anecdotes about his varied career from Hackney schools to Downing Street to the Punjab, Barber’s worldview is at once very generation specific, and yet surprisingly timeless. He is thought of as a classic ‘Blairite’, and the majority of Barber’s insights sometimes have the whiff of overzealous ideology-masking-as-not-ideology that characterised ‘Third Way’ thinking, of the sort espoused by many other New Labour alumni including Philip Gould, Geoff Mulgan, Alan Milburn, and Peter Mandelson. This includes over-excitement about ‘disruption’, ‘innovative delivery’, and a certain mistrust and cynicism about political opposition to reform, particularly if it comes from public sector staff and officials.

And then there’s the matter of targets (we’ll get to that…).

Barber and his ‘deliverology’ were frequently mocked by the New Labour Brownites, and later by David Cameron while in opposition, and many others in the world of public policy. Liam Fox wrote in 2008 that “a future Conservative Government must see the target culture as one of the main state bureaucratic institutions to be removed”. Yet the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit, abolished by the Coalition in 2010, was revived in 2011 as the Policy and Implementation Unit after Cameron found his own need for a ‘scientific’ approach to governing from the centre. Significantly for universities, Jo Johnson served as head of the Policy Unit from 2013 to 2015.

Not even the accession of Theresa May, herself seemingly less interested in the ins and outs of public service delivery than her predecessor, has prevented Barber’s continued looming presence over Whitehall. Only a month ago, Barber was also appointed to a new Treasury role “to advise government on how to make efficiency central to its culture and practices”.

Once one reads How to Run a Government, Barber’s legacy across Whitehall becomes clear, and there are some very clear ways in which the Higher Education and Research Bill, and particularly the TEF, indirectly bear his influence. I would not be surprised if a well worn copy sits on Jo Johnson’s bookshelf.

Trust and altruism

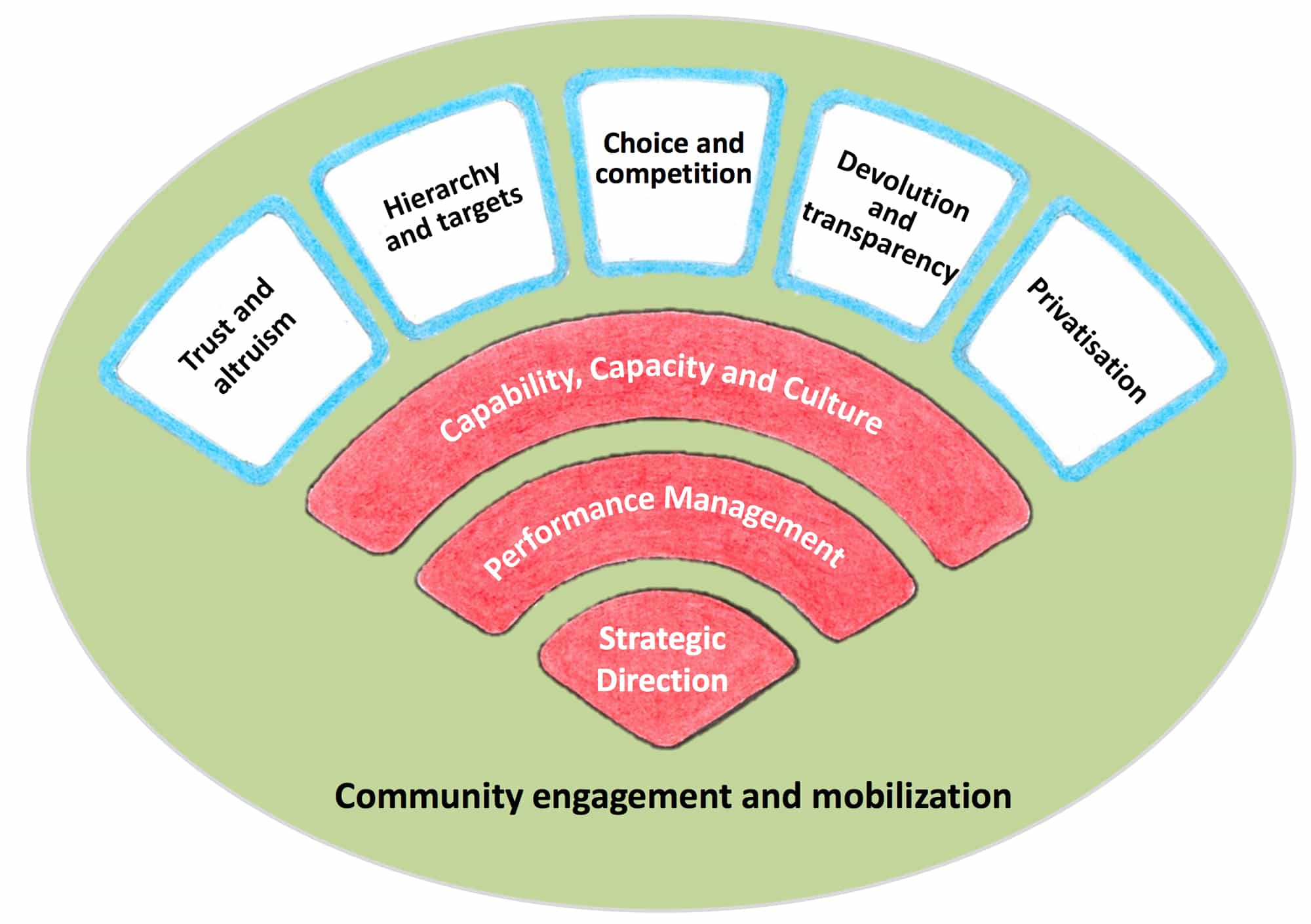

One of the most interesting parts of How to Run a Government examines the different ways that governments can run and reform public services.

Michael Barber’s ‘five paradigms of system reform’

On the far left (both literally and figuratively, in Barber’s eyes), the method of ‘trust and altruism’ is still highly cherished in higher education. The sector as a whole has invested extensive political capital in ensuring its ‘autonomy’ is protected in the Higher Education and Research Bill. Yet Barber’s approach to policy thinking revolves around near outright rejection of trust and altruism, which he says “assumes that all public sector professionals are knights, not knaves”. The implicit flipside of trust and altruism, for Barber, is ‘provider capture’.

How to Run a Government is curiously shallow in picking this apart. Barber cites research by Gwyn Bevan (LSE) and Deborah Wilson (Bristol) comparing school and hospital outcomes in England and Wales which concluded that the trust and altruism model “has been found wanting” in comparison to systems that introduce targets, objectives and incentives for good performance. Yet he also briefly nods to examples where the approach appears to work in other countries, such as in Finland’s much-admired schools system, without considering how some of the conditions of that success might be imported into any public policy initiative in the UK. Trust and altruism are batted away swiftly, as Barber moves onto other considerations.

The debate over the merits of trust and altruism strikes at the heart of some of the opposition to the present round of higher education reforms. ‘Autonomy’ and ‘co-regulation’ are effectively means of professional trust and altruism. If the past few years of government activity have told us anything, from the Browne review, to the 2011 White Paper, to the drama over the future of QAA, and now TEF and the new Bill, it’s that trust and altruism simply won’t cut it with Whitehall officials and politicians across political parties.

The incoming regulatory framework for higher education will thus largely be a hybrid of three of the other four ‘paradigms of system reform’ that Barber highlights: choice and competition, devolution and transparency, and privatisation. This largely explains why the new ‘higher education market’ will also be quite heavily regulated through a complex bureaucratic process like TEF, to the bemusement of many in the sector. To a certain extent, Whitehall is still going through a process of trial and error, mixing and matching choice and competition, transparency and league tables, and outright encouragement of new private provision.

Metrics and transparency

Barber and his generation of New Labour advisors became synonymous with ‘target culture’ and metrics: for police, schools, hospitals, immigration, and more. In How to Run a Government Barber shows himself surprisingly willing to engage with critics of this approach, despite a certain degree of fatalism and defensiveness: “Since governments, whether they like them or not, are going to set targets, we might as well have the real debate about them”.

Opponents of TEF frequently cite Goodhart’s Law: “that any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes”. Barber’s explanation for some of the perverse incentives that can be created by relentless target setting is surprisingly open-ended. He argues that “there is a moral purpose behind every target” that should never be forgotten. That said, Barber believes that opposition to any type of target or use of metrics on the grounds of perverse incentives can be a smokescreen rather than an honest critique; an attempt perhaps to revert to trust and altruism?

We saw this in the debate over the TEF in the House of Lords. Baroness Wolf, in particular, cited Goodhart’s Law and the danger of the exercise creating perverse incentives. Some of these were feasible, and others less so, such as the suggestion that the exercise would kerb freedom of speech as universities “cater to the demands of a generation of sensitive ‘snowflake’ students”.

The debate about perverse incentives also crops up in criticism of REF and other research evaluation exercises, so much so that there is an emerging body of evidence that ‘publish or perish’ is undermining the integrity and ‘reproducibility’ of scientific research. And then there is the tragic suicide of Stefan Grimm at Imperial College London, ostensibly as a result of pressure to meet performance targets.

Finding the middle way (dare I say it, Third Way?) between unaccountable trust and altruism and overbearing and perverse target metrics is one of the biggest challenges facing universities and policymakers in the sector today. Some of the most useful interventions in this area include the review of ‘responsible metrics’ in research assessment led by James Wilsdon and the intelligent guidance on using NSS results in enhancement from Alex Buckley.

Even Barber himself is alive to the challenges in this space, and How to Run a Government has some useful lessons for anyone responsible for improving policy, delivery or performance in either universities or public services more generally. Barber emphasises the importance of learning from experience and refining policy where necessary; of the importance of recognising and balancing the competing interests of government, users and the professions; of triangulating performance measures with alternative datasets. This is all easier said than done perhaps.

TEF, reforms to REF and the creation of a new regulator will only intensify questions about the relative merits of the approaches both promoted and rejected by Barber, and the man himself will now be at the heart of resolving these complex problems. One of the reassuring things from reading How to Run a Government is that, agree or disagree with him, there are probably few people who have thought about these problems more extensively.