If you asked universities leaders this question back in 2016, it’s fair to say that the answer from most of them would have been “not much” or “through our international students and Transnational Education (TNE)”.

Prior to Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s also fair to say that the UK’s general approach to international trade and investment was very much of incidental importance to both national and local government. After all, the EU dictated our trade policy and our inward investment pitch to the world’s businesses was extremely strong – combining liberal rules on foreign ownership, our reputation for rule-of-law and almost frictionless access to the European single market.

In this former world a few universities dipped a toe in the annual Cannes MIPM real estate jamboree alongside local partners, sent representatives on delegations to trade fairs around the world and maybe hosted some visiting dignitaries. A slightly larger number of universities (and entities such as Invest in Northern Ireland or the East Midlands Chamber of Commerce) set-up placement programmes that connected students and graduates with local SMEs to explicitly help them with international trade and export projects.

Everything isn’t fine

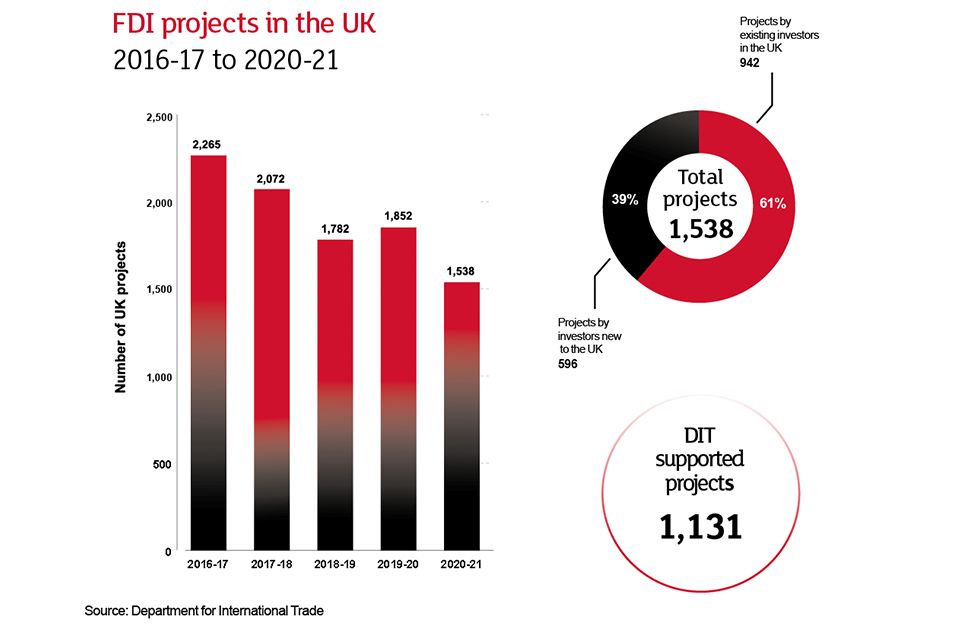

Fast-forward to today and this picture has significantly changed. The national decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) since 2016 is only just starting to creep back upwards – the latest DIT figures for 2021-22 show a slight increase (51) in FDI projects from the previous year. However, export and trade figures are nothing short of catastrophic – and outside of London and the South East, these trends and their impact on economies and businesses are more severe. Local and regional leaders have noticed this impact and are starting to ask “who is responsible for this and who can help us?”

The answer to this question (in England at least), lies in an absurdly fragmented, complicated and under-resourced melange of different organisations that sit across multiple geographies. As per the last decade of a post-regional development agency laissez faire approach to sub-national economic development, this environment is rife with the overlaps, gaps and flaps that are an inevitable consequence.

Meanwhile, ONS data shows that 2020-21 saw a 6 per cent decline in overseas investment in university R&D, the first drop since 1999 and a pretty big one at that. As a recent IPPR report demonstrates, the UK is going to struggle to unlock private sector investment into R&D without taking a more proactive approach to attracting international funding. And, following the National Security and Investment Act and the development of the Trusted Research agenda, it is clear that universities are going to have pay a lot more attention about where this international investment comes from.

What should universities be doing about it?

In this context, what – if anything- might the role of universities include and how might they approach the international trade and investment agenda? At the beginning of this year with the support from the Department for Levelling Up, Communities and Local Growth and local partners, the BEIS Tactical Fund, and a coalition of fifteen universities in the midlands, led by the Midlands Innovation and Midlands Enterprise Universities have started to explore these questions.

Very quickly it became apparent that the topic of FDI and university R&D was of significant interest to policymakers across Whitehall and universities across the UK. It was also apparent that the devolved administrations (Scotland in particular) were some way ahead of the English regions both policy and practice. To pull together some of this thinking, case-studies and evidence we started working with Universities UK International (UUKi), the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) and the National Centre for Universities and Business’ (NCUB) on a research and policy report that will published in the coming months. Following a roundtable held with UKRI this summer we have widened our scope to collaborate with colleagues in Manchester, Strathclyde and the Scottish Government who are also working on the UK’s three Innovation Accelerators.

Whose FDI is it anyway?

Unsurprisingly for a pilot involving universities, one of our first tasks has been to establish some working definitions. Universities interact with FDI both as a direct recipient, but also as a major factor in the ability of the UK and regional economies to both attract new FDI and grow it once it’s been landed.

We have come up with a fairly broad-brush taxonomy for FDI into university R&D :

- Space: companies using physical space in science, technology, innovation and enterprise parks – sometimes including access to sector-specific facilities like wet labs or demonstrators.

- Research base: direct investment into universities research. Everyone’s favourite HESA Table (DT031 – Table 5, it’s a cracker) tracks industry income into UK universities by region, cost-centre and destination of investment (UK, EU or rest of the world).

- Commercialisation: equity investment into university spin-outs (including exits, which is often ‘bad FDI’ in terms of the UK losing the longer-term economic benefit of the IP), licences and patents. Following Oxbridge’s lead, UK universities are increasingly banding together to create bigger funds to attract more ambitious investors.

In terms of the role that universities play in attracting FDI, whilst compiling the £86bn 2022 Midlands Investment Portfolio we tracked at least 20 initiatives directly involving universities, worth Over £10bn in GDV with the potential to create over 30,000 jobs in the region. These tended to have been developed through various mechanisms involving DIT and (where they exist) local growth companies. Examples of this include the High Potential Opportunity Areas, Freeports and Life Science Opportunity Zones.

What does trade and investment mean to your university?

In conversation with universities across the midlands we started with this question – and it quickly became apparent that institutions were approaching things very differently. Strategies varied depending on the type of university, their specific local context (i.e. whether they had a functioning growth company, the focus of their local enterprise partnership or combined authority) and the sectors they had research and knowledge exchange strengths in. Despite this, across all midlands universities 37 per cent of their industry income in 2020-21 was from overseas (the vast majority non-EU).

The midlands pilot is just starting to scratch the surface of this topic – and the implications for universities, local partners and government. However, as part of the national research and policy report with UUKi, HEPI and NCUB we are keen to hear from institutions across the UK, be this ideas, suggestions or examples of best-practice we can highlight and emulate. Future blogs will also focus on the role of universities in supporting trade, exports and the local visitor economy.

Please get in touch by emailing Alex.Favier@midlandsinnovation.org.uk