The Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA) is still at the heart of disability support for students in HE. Recent reforms to the DSA have monopolised professional thinking on disabled students in universities. But precisely because the DSA is receding, the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) will have a major impact on how disabled students are supported at university.

The DSA funds individual students’ support at university, directly from the government. Cuts mean universities must do more. Universities aren’t obligated to replicate the exact support that the DSA used to fund, so future support for disabled students will be non-standardised and difficult to predict. Instead, the government has merely reminded universities of their general obligations under the Equality Act. This puts disability departments in a tough spot, arguing for more money simply to maintain the same level of service. Disabled students are bound to worry that some universities won’t do enough to prevent things getting worse overall.

To be clear, the DSA still matters and it may be with us for years to come. But its future is uncertain and it has already been cut substantially. Disability access depends increasingly on universities’ willingness to invest in their support services. To ensure that cuts to the DSA don’t make higher education less accessible, we need to look at the wider policy context in which universities’ set their priorities, and this of course includes the TEF.

Access to excellence

The TEF sets out three defining aspects of quality – learning environment, student outcomes, and teaching quality – and under these headings it lists important contributors such as contact time, extra-curricular activities, and links to the professional world. It does not mention the need for teaching to be accessible to disabled students.

Of course, general principles can’t be too detailed. But an appropriate analogy might be software design, where engineers have found that if accessibility isn’t included among the goals, it is hard to retrofit. If access for disabled students were part of how the framework defines quality, it would encourage universities to think about access from the very beginning of their strategic planning.

However, the TEF does incorporate disabled access when it comes to measure excellence. If a university scores particularly poorly with regard to disabled students then, even if it does well overall, the result is ‘flagged’ for further scrutiny. Failing to maintain services for disabled students could undo a university’s general efforts to place well. This gives universities a powerful incentive to try to plug the gaps left by DSA cuts.

Specialising in the splits

The TEF doesn’t just give universities a reason to fear underperforming in regard to disabled students, it also creates an incentive to try to exceed the norm. The TEF includes metrics on student satisfaction, retainment and post-degree employment. Because each university has a different mix of students, the metrics are split by types of course and student characteristics. Disabled students are one of these ‘splits’. The satisfaction feedback they give and their (highly skilled) employment rate will be compared separately.

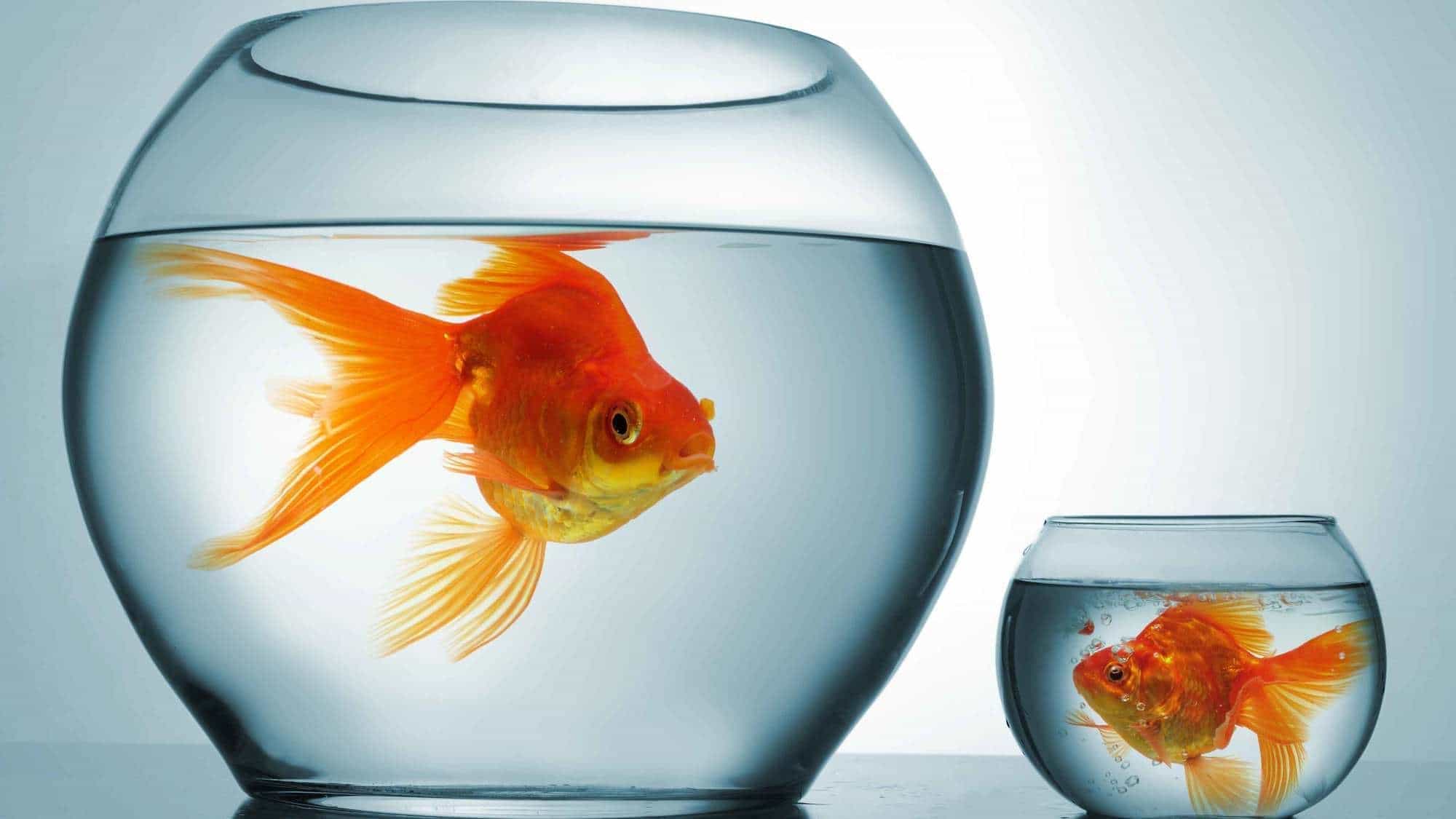

On average disabled students give less positive feedback in the National Student Survey and are less likely to get highly skilled jobs. The purpose of this metric splitting is to avoid penalising universities that have lots of disabled students. But the weighting system could also give universities an incentive to target disabled students as a central part of their TEF strategy.

Where disabled students give positive feedback and get highly skilled jobs, this counts for more than the same for non-disabled students. A university could invest heavily in support for disabled students in order to outperform the sector average. The positive outcomes and experiences of disabled students could make a major contribution to an institution’s overall score.

This strategy might make particular sense for an institution with a large disabled population, if it can take advantage of economies of scale. Some universities might even specialists in disability access, by funding individual support over DSA levels, redesigning courses and learning materials with access in mind, and building links with employers that have good records on disabled hiring.

Rights and specialisation

The prospect of some universities excelling in their teaching of disabled students must be welcomed. But variation in quality challenges the rights-based rationale of disability support. If a student wants a university with good sporting opportunities she must prioritise this over other features, but many will not be comfortable with disabled students having to trade-off accessible teaching and, for example, their favoured degree subject or university location.

A rights-based approach to access must also reject the idea that more accessible institutions should be able to charge higher fees as a consequence. After all, such an institution will have only succeeded in providing equal access for disabled and non-disabled students. The Disabled Students’ Allowance avoids this problem because it is granted to the student wherever they study. Yet as the DSA plays a smaller role, the disparity in support between institutions will inevitably increase with or without the TEF. TEF offers a rationale for universities to make accessible teaching a central part of their work.

The way disability is defined in the statistics doesn’t help though – it’s basically ‘disabled entrants’. If my understanding is correct – if the disability doesn’t persist, you’re still counted as ‘disabled’ for your full time at University; and if your disability is not declared in your first year you simply aren’t counted as disabled. Both real counter-pressures to effective support for students wit disabilities now.

If the government insists on having it this way then they should take on the responsibility of routinely assessing all pupils for dyslexia and any other SpLd while they are still at school. This is clearly not happening at the moment and the result is that students do not begin to suspect they have dyslexia until perhaps their second or third year at university. I have always felt particularly sorry for the very brightest of our dyslexics – the ones who scrape by with no help until the third year and then can go no further. The way they are… Read more »

I completely agree! My disability was never detected through school or college even though my reading was slow and my writing was terrible – and it was only because I requested a test to determine any difficulties that even found out I was struggling with dyslexia among other things. I didn’t start this process until my third year, by which point it already felt too late. It took months to get any kind of support, and with deadlines looming it was far easier to just try and cope than it was to attend study support sessions as they just added… Read more »

Some great points made, thanks. The decline of DSA funding can prove challenging but the biggest challenge is a positive one: creating accessible teaching and learning experiences improves quality for everyone. It also encourages effective use of technology which helps narrow the gap between 21st century learners and 19th century teaching methods. There’s a Jisc blog on this topic also with loads of useful links (apologies for long url!)

https://www.jisc.ac.uk/blog/minimising-pain-maximising-gain-top-tips-for-supporting-learners-affected-by-dsa-changes-19-feb

Great content,thanks for sharing. Picked up some good and valuable insight.

Disability Kingston