The Labour Party, the Lib Dems and the Greens have all published their manifestos for the 2019 General Election.

The politics of fees gets the headlines and the retweets, and the potential impacts of policy on university finances always gets a good going over by the sector, who will be worried that Labour’s “free fees” pledge would be accompanied by student number controls and a reduced unit of resource. But what have the supposedly progressive parties – who may yet end up forming some kind of coalition in the event of a hung parliament – got to say about the amount of money that students will have?

My grant cheque lies over the ocean

The Greens’ manifesto doesn’t even mention it, but both the Lib Dems and the Labour party have pledged to “reinstate maintenance grants for the poorest students”. What exactly does that mean? For the Lib Dems, the detail is missing from their manifesto, but their front bench team has framed this in media appearances as an intended reversal of George Osbourne’s Budget 2015 decision to remove the maintenance grant and replace it with more maintenance loan.

Interestingly, the Labour approach is basically identical. Buried in the party’s “Funding Real Change” manifesto annex, the maintenance grants proposal is revealed to be based on the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimate in their 2019 “annual report on education spending in England”. And that work also assumes that Labour will return to the pre-2016 maintenance grants and loans regime.

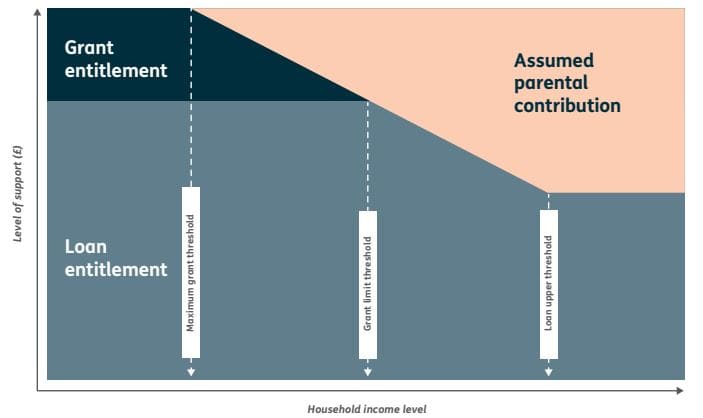

When they were abolished, 400,000 students got a full grant and just over 136,000 got a partial one via means testing. They were worth a maximum £3,387, with a maintenance loan top-up and a hidden “assumed parental contribution” for those that didn’t get a full grant. Back then, the “fiscal illusion” meant that lending money to students – even if the state wasn’t likely to get it back – flattered the budget deficit. So as well as swapping grants for loans, maximum cash support (living away from home outside London) in the form of maintenance loans actually increased to £8,200 per year from £7,400 for those outside of London.

My grant cheque lies over the sea

The problem is that it wasn’t enough then, and it’s certainly not enough now. That £8,200 is now £8,944 thanks to inflation, but DfE’s own analysis of its “Student Income and Expenditure” survey for the Augar review found that median expenditure by full-time students living away from home and studying outside London was £11,679 in 2018/19 prices. Even that was a flawed guess – to get there DfE officials just uprated (using RPI) numbers in the 2014 Student Income and Expenditure Survey, ignoring that the rent component of those calculations consistently rises faster than inflation.

So if we do switch back to that pre-2016 mix of means tested grants and loans, students (and/or their parents) will still face a significant shortfall. It’s not necessarily a shortfall that manifests in students not applying. It’s a shortfall that manifests in students scrimping on learning materials, working full time hours in bars, having no social life and dropping out. It’s a shortfall that exacerbates the mental health crisis and guarantees that those students affected will end up with much worse outcomes than their peers. It’s a shortfall that means they can’t join in.

For many, additional borrowing acts as the top up. Back in June we heard that the average graduate now leaves university with £3,561 of debt on top of their student loan – with 15 per cent leaving with over £10,000 worth of debt. None of that is going to wiped, even by a Labour government having a think about historic student debt in the next parliament.

And it gets worse. Universities UK regularly calls for the return of the grant, but when it comes to institutional support in the form of bursaries and scholarships, many of its members have taken advantage of OfS’ relaxation of Access and Participation rules and reduced or narrowed support. They’ll be even more keen to do so if the unit of resource gets squeezed. Sadly, we don’t yet know the full extent of the retrenchment – the regulator’s review of published APPs is another victim of the pre-election period publication ban – but it’s likely to be significant.

Bring back my grant cheque to me

My social feeds indicate that the grants proposal, particularly when coupled with Labour’s tuition fees proposal, is popular. There’s a perception that it will genuinely help ease costs whilst at university and reduce repayments on graduation.

But there’s a vicious irony here. You may remember that buried on P192 of the Augar Review, the panel admitted in its similar grants proposal that it expected “the additional call on public funds from this proposed change to be fairly modest”. How? Well, as career earnings tend to be lower for graduates with lower prior attainment and from disadvantaged backgrounds, “that level of foregone loan repayments from students from low-income households is likely to be low”. In other words, a poorer student that right now graduates with £55k of “debt” may well have had £40k of that written off in 30 years. If in the new system they graduate with £15k of debt, they’ll pay back exactly the same as they would now – every month – for all 30 years.

Put another way, the financial impact on current students will be nil. The financial impact on graduates could also be nil. And when you add to that the continuing problem with rent, and the unsolved issues of London, students with children, estranged students and commuter student assumptions (as well as the well documented squeezed middle issue) and the truth is that day to day and on graduation, the actual impact of not acting on maintenance maximums will be hugely negative.

All of this would be bad enough, but Labour’s calculations hilariously assume that student numbers will actually fall in the next five years. That budget annex says “projections for the number of FT undergraduates [are that they will] decline in the forecast period due to a falling number of 18 year olds”. I don’t know which set of projections party staff have been looking at, but it’s certainly not either DataHE’s or HEPI’s.

Shame on you for turning blue

The utterly shameful thing is that my feeds suggest that the majority of young people won’t realise that the maintenance loan is here to stay, and that the vast majority of students will still graduate with 30k worth of maintenance loan debt that they’ll spend most of their life paying off – having spent it all filling the coffers of baby boomer HMO landlords and greedy PBSA investors.

There are of course perception and confidence benefits. It certainly sounds different to the old system. But here’s the thing. Either you think that being a student at university day to day is affordable now, and the change will convince more that it is – or you don’t think that being a student is day to day affordable now, and the change will trick people into thinking it is when it isn’t.

The available evidence points to the latter. And if I’m right, that’s one of the nastiest confidence tricks played on poorer students with educational ambitions that it’s possible to imagine.

“that the vast majority of students will still graduate with 30k worth of maintenance loan debt that they’ll spend most of their life paying off” and, like the council housing sales of the past is the key, once you’ve got a home and mortgage the leverage employers and Government have over you means you’ll keep working to keep it, defaulting on the loan payments may well mean a bad risk flag and no mortgage, or once mortgaged if you default they’ll go after your assets i.e. your home. Thatcher well understood once former council house tenants were mortgaged up buying… Read more »

Who’d have though Maggie’s policy would suit Labour and the others, back then no one, now it’s just another ‘means of control’ to be exploited.