Targets for widening access are becoming of feature of government across the UK. The achievability of the target set for England has already come under scrutiny. In Scotland, by contrast, there has been very little questioning of the ambitions set for the system.

Yet an examination of data recently released by the Scottish Funding Council shows that what is being asked of institutions is at least as demanding as the English targets, if not even more so.

What are the targets?

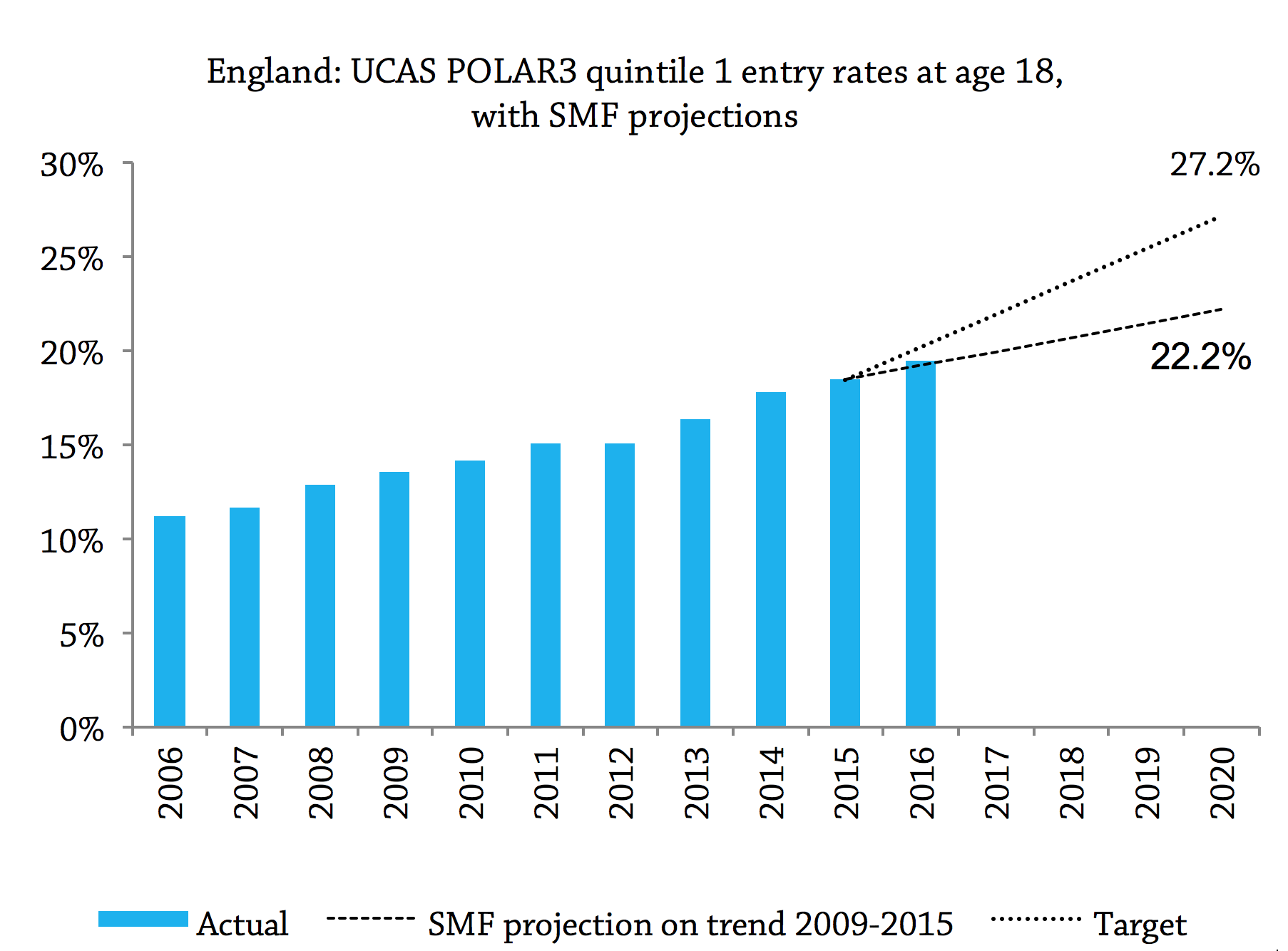

In England, the government has announced that by 2020, it wants to double the proportion of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds entering higher education, compared to 2009. Using the entry rate through UCAS for 18 year olds as a proxy for this, the Social Market Foundation last year calculated that this would require an increase in the entry rate from 18.5% in 2015 to 27.2% in 2020. It argued that the system’s steady but slow rise was heading instead towards a position 5 percentage points below that by 2020.

The graph below reproduces the SMF’s figures, with the actual 2016 entry rate added. The 2016 figure was slightly above the SMF projection, but still well below what it estimated would be needed to meet the target. The SMF also highlighted the large variation between institutions, in absolute levels and trends over time.

Sources: UCAS, SMF

In Scotland, the government’s targets come from last year’s report by the Commission on Widening Access, which recommended that (emphasis added):

By 2030, students from the 20% most deprived backgrounds should represent 20% of entrants to higher education.

Equality of access should be seen in both the college sector and the university sector. To drive progress toward this goal:

- By 2021, students from the 20% most deprived backgrounds should represent at least 16% of full-time first degree entrants to Scottish HEIs as a whole.

- By 2021, students from the 20% most deprived backgrounds should represent at least 10% of full-time first degree entrants to every individual Scottish university.

- By 2026, students from the 20% most deprived backgrounds should represent at least 18% of full-time first degree entrants to Scottish universities as a whole.

- In 2022, the target of 10% for individual Scottish universities should be reviewed and a higher level target should be considered for the subsequent years.

The Scottish Funding Council has added a further target for the final year of the period covered by its current round of access agreements. It expects 15.5% of entrants to higher education to be from the most disadvantaged 20% of areas by 2019-20.

The distinction between higher education and universities (or HEIs, a category comprising universities plus three other specialist higher education providers) is important, because ‘higher education’ includes the substantial amount of HN-level higher education provided in colleges in Scotland, which already have intakes that are relatively well-balanced by social background. It is in the universities where unequal access persists.

The remit of the Commission was to think about access to universities specifically. However, the Commission’s report looked more widely, and the newly-appointed Commissioner for Fair Access, Sir Peter Scott, was keen to stress last month, in his initial hearing with the Scottish Parliament’s Education and Skills Committee, that he saw his brief as extending across all higher education:

The major thing that I can do is not to focus too strongly on just the universities’ contribution and to give greater recognition to what colleges can and do deliver.

As worded, the 2030 target (and the SFC’s interim target for 2019-20) could technically be met by including colleges as well as universities, and also including full-time as well as part-time students. To do so would make the task much easier. However, the 2021 targets quoted above are clearly about full-time entrants to universities.

Here the numbers released last week by the Scottish Funding Council are particularly useful. They provide the nearest thing we have to a statistic measuring its focus: the percentage of all undergraduate entrants to universities/HEIs from the most disadvantaged areas.

The SFC statistics are not a perfect reflection of that target. They are only for full-time entrants under 21. Adding older entrants would almost certainly boost the share of students from disadvantaged areas, but the overall effect across the system as a whole might be expected to be modest. The Cabinet Secretary, John Swinney, last week suggested that including older entrants had a substantial effect (more below), but it is not clear at what point statistics which include older entrants will be published.

On the other side, the SFC figures exclude entrants from outside Scotland, who tend to be more advantaged than the Scottish student body as a whole. Although it is not explicitly limited in this way, I assume here that the target is concerned with the percentage of disadvantaged Scots as a proportion of all Scottish students. If not, then the challenge is much greater, and the gap much wider, than shown below. I am encouraged in focussing on Scots by the Access Commissioner’s interpretation of his remit:

I see the primary responsibility of my role—and I think that this was the prime focus of the commission—as being to focus on fair access for Scotland-domiciled students. I do not think that I have any remit to make access fairer for students who come from England or Wales to attend Scottish institutions, although I accept that the social composition of those students changes the flavour and affects the culture of at least some Scottish universities.

The SFC data

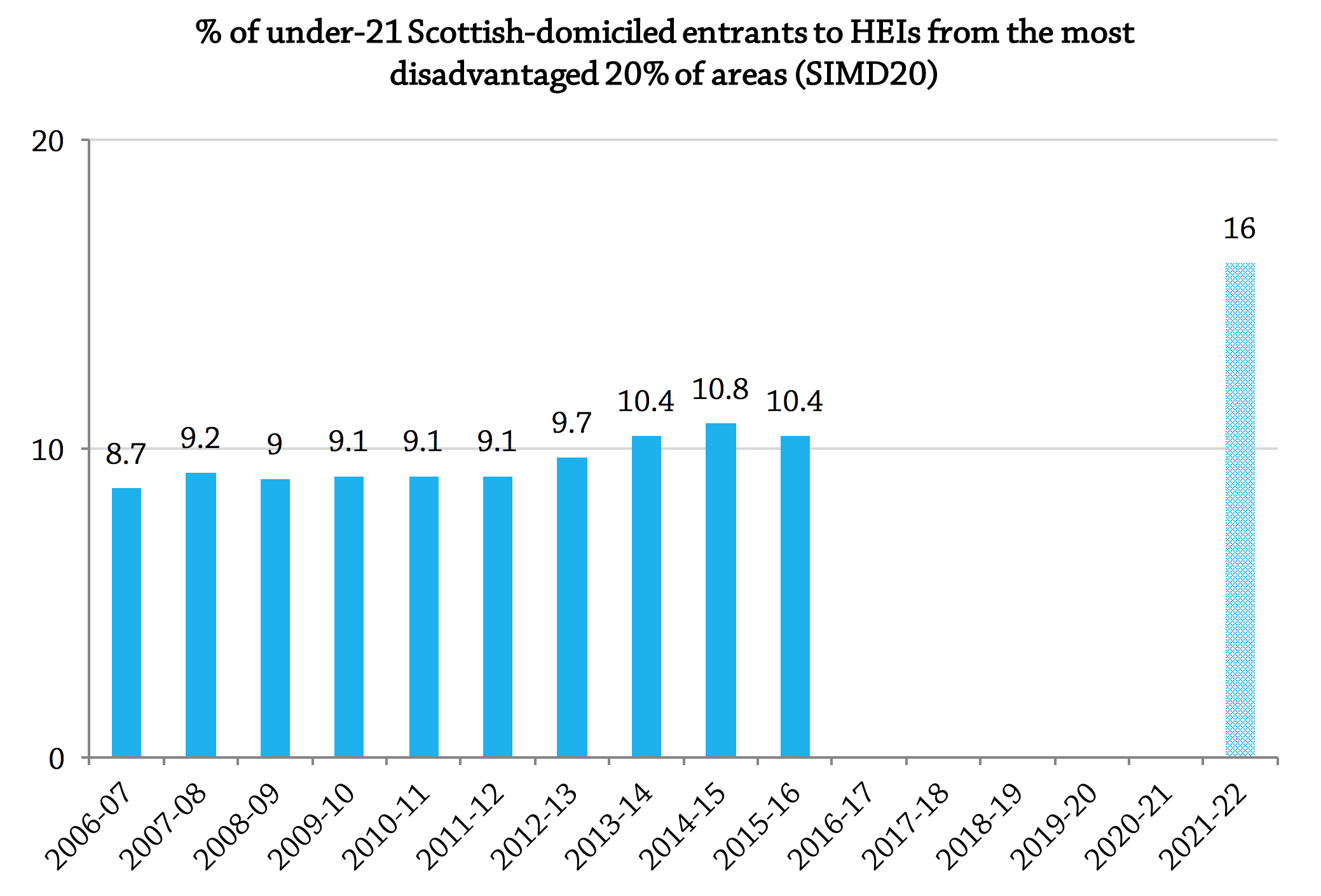

Here’s the total proportion of under-21s from the most disadvantaged 20% of areas (SIMD20) since 2006-07, with the 2021 (all age) target added for comparison.

The trend has been generally upwards over the decade covered, but it is harder to project any kind of trend line from these figures than it is for England, particularly given the fall in 2015. Universities Scotland has recently described 2015 as a “blip” year for applications from this group. The recent step up will be due to the addition in 2013-14 of extra places ring-fenced for widening access (more on the effect of that here). But at first sight intervention on a completely different scale appears likely to be needed over the next five years, to reach an average of 16% across all HEIs.

Although this graph suggests that Scotland looks to face at least as great a challenge as England in meeting its turn-of-decade target, John Swinney last week quoted the average as already being 14%, appearing to have access to all-age data which closes the gap very significantly. Publishing all-age data alongside that for the under-21s would certainly be a useful step in clarifying the scale of the task.

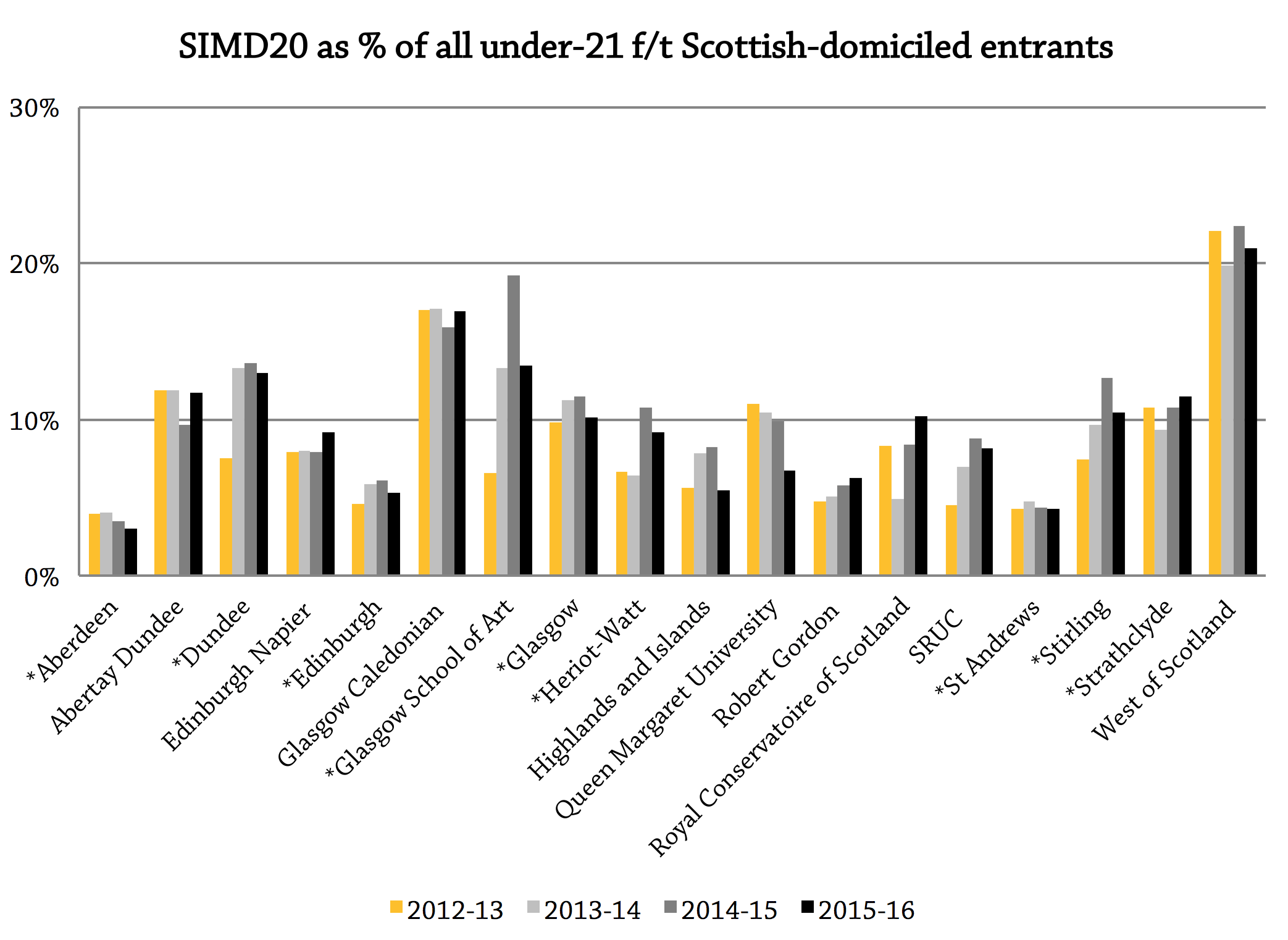

The target also includes a minimum of 10% for individual institutions by 2021. Figures for the last four years are shown below for each institution. 2012-13 is marked in yellow, as it was the last year before additional places were released. Those institutions marked * received some of these places.

Only four higher education institutions have been above 10% for each of the last 3 years (Dundee, Glasgow Caledonian, Glasgow School of Art and the University of the West of Scotland). Seven have never crossed this line: of these Aberdeen, Edinburgh, RGU and St Andrews are all below 7%. The remainder have hit 10% at least once in the past three years, though some are more consistently close than others.

There is, noticeably, a lot of volatility at institutional level. Many institutions show no clear trend, despite the emphasis placed on widening access in recent years. Of those receiving extra places, Dundee, Stirling, and Glasgow School of Art stand out for increasing the share of their students from disadvantaged backgrounds and sustaining that.

In short, getting everyone over the 10% line by 2021 looks very hard. Keeping them there looks harder still. The institutions with furthest to go also tend to be those with younger intakes, thus adding older entrants is least likely to help.

Getting to 2021

There has been no real recognition in Scottish political debate of how demanding these targets are. Nothing equivalent to the SMF’s report on England has been produced. The only real controversy has been about the impact on other entrants of seeking growth in one group, while not expanding the system as a whole. The achievability of the targets, however, has not been called into question, in public at least.

That may be starting to change. At Committee the Peter Scott had this to say:

I suspect that some of my responsibility might be to manage down expectations about what the Commissioner can deliver.

That seems absolutely fair. At the same session, the Commissioner clarified that he has only a 3-5 day a month appointment, with no assigned budget, at least as yet. It’s a much more low-key arrangement than the Director of Fair Access in England; no doubt deliberately so. Sir Peter also stressed that he wanted to take time to understand the situation better and was not yet ready to move into “pro-active mode”. His first annual report is due in a year’s time, that is, early 2018 – less than three years before applications will be submitted for entry in 2021, and less than a year before applications begin for 2019, the year for which the SFC has set its first round of specific ambitions.

So time is tight, and these targets are tough. A system which increased the share of the most disadvantaged young people from 8.7% to 10.8% over a decade, with the help of dedicated additional places, is now expected to increase by at least a further 2 percentage points, and perhaps rather more (depending on what to make of Swinney’s new figure), in just six years, with no promise of further expansion.

Over half of institutions will need to substantially improve (in one case more than double) their performance over the same period. Even if including older entrants provides a large boost – as Swinney’s recent evidence to committee suggests – the ambition is still astonishing.

I can only wish everyone involved good luck. It’s not that these targets can’t be met, but some acknowledgement of the challenge involved would be good first step.