Since the introduction of £9,000 fees in 2012/13, there has been growing concern in relation to the burden faced by graduates over their working lives.

Although the fee and maintenance loans available to English-domiciled undergraduate students are income-contingent, the associated interest rate charges as well as the current freeze in the loan repayment threshold imply that many graduates will face high loan repayment commitments over the entire 30 year repayment period, with many facing limited prospects of ever repaying their full loan.

Though the student loan repayment system appears progressive, and is a regularly cited argument in its favour, the analysis that follows illustrates that it can be regressive.

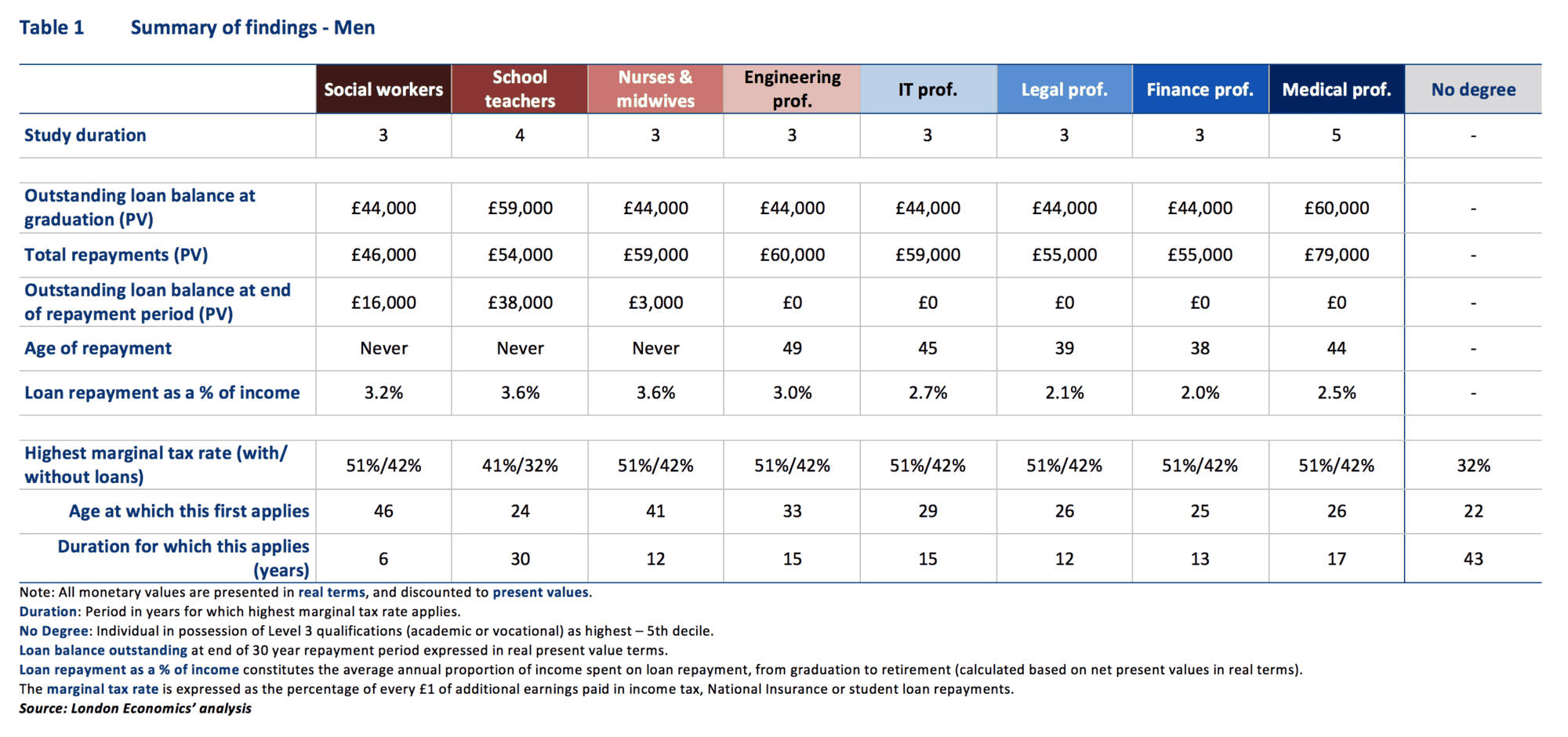

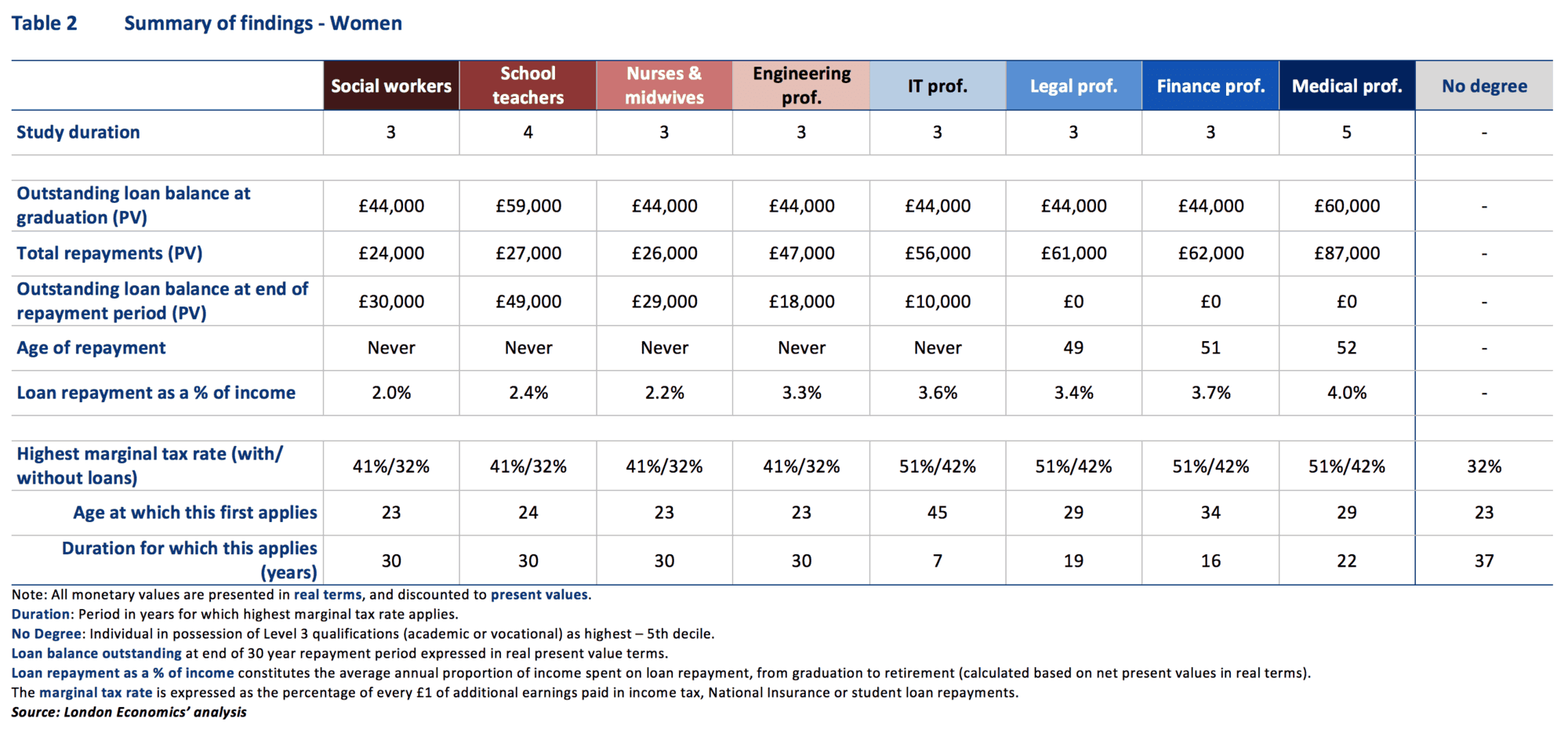

We assessed the lifetime costs associated with receiving and repaying student loans for individuals starting full-time undergraduate degrees in 2016/17. In addition to the loan balance on graduation and repayments made (in real terms – i.e. constant 2017 prices, and discounted to reflect net present values), the analysis estimates the average and marginal income tax, National Insurance and loan repayment deductions in a number of graduate professions (spread across the earnings distribution) including:

- School teachers

- Social workers

- Nurses and midwives

- Engineering professionals

- IT professionals

- Legal professionals

- Finance professionals

- Medical professionals

What did the analysis show?

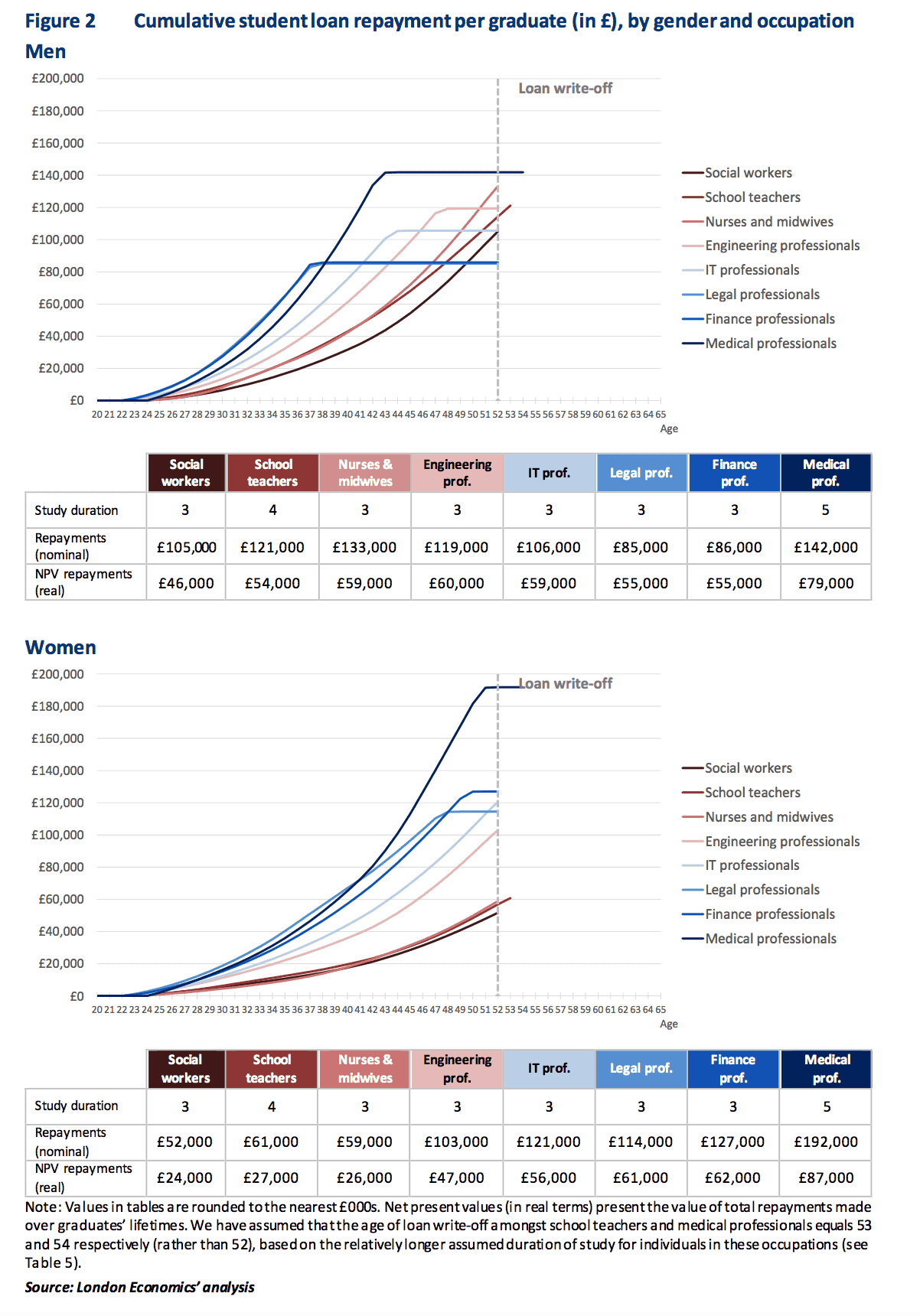

We estimate that for those individuals in receipt of three years of student support, the average level of debt at graduation (including interest) stands at approximately £44,000 in real present value terms. Because of the extended duration of study, this increases to between £59,000 and £60,000 for those entering the teaching and medical professions.

Based on their relatively low earnings, male teachers, social workers or nurses will not be expected to repay the entire loan balance by the end of the 30-year repayment term, with between £3,000 and £38,000 outstanding at the point of write-off. In the case of teachers, in spite of making £54,000 in repayments, these individuals spend 30 years paying accumulated interest on their loans. This compares to male financial service professionals, who make a similar level of repayment (£55,000), but make higher repayments immediately upon graduation, and are thus expected to be able to pay off their entire debt by the age of 38. Men in teaching profession have earnings between the 4th and 5th deciles of the overall earnings profile, while men in financial sector occupations have earnings between the 8th and 9th deciles.

A similar outcome applies to women in occupations with above-average earnings, such as IT professions, who make approximately £56,000 in loan and accumulated interest repayments. Despite a £10,000 outstanding balance existing at the end of the repayment period, this still represents a greater level of repayment (in real present value terms) than men in financial or legal occupations (£55,000).

Income-contingent loan repayments: progressive or regressive?

At a particular point in time, the income-contingent loan repayment system is progressive (and is often argued as such by its advocates). However, how can this marry with the fact that certain lower paying occupations are expected to make larger loan repayments – in real present value terms – than higher paying occupations? It comes down to the duration of repayments.

For example, for as long as it takes men in legal professions to repay their entire student loan and accumulated interest (16 years), the average level of student loan repayments as a proportion of income stands at between 4% and 7%. For teachers, whose earnings are lower, the average contribution ranges between 2% and 5% in this period. Hurrah – the system is progressive!

However, from the 17th to the 30th year of repayment, while those in legal occupations have no further repayments to make, teachers continue to pay around 5% of their total earnings in loan repayments. As the table above illustrates, men in public sector professions – with median earnings (or slightly below) – face a greater loan repayment burden over their working lives than higher paid individuals, who repay their loans early. Compared to men in financial or legal professions, who pay an average of 2.0%-2.1% of gross earnings towards the costs of repaying their student loans, men in social work, teaching and nursing occupations pay between 3.2% and 3.6% over their working lives.

Similarly, for women in relatively higher-paying occupations (legal and financial occupations), the average level of student loan repayment as a proportion of earnings across the working life was estimated to be between 3.4% and 3.7%. This again suggests that individuals near the middle of the earnings distribution are disproportionately impacted by student loan repayments over the course of their working lives.

The incentives appear to be to either repay as soon as possible, or not at all. However, those who are just on track to clear the balance at the end of the 30-year period face a 9% payroll deduction over their working lives, and repay more in real terms than both lower earners (fine!) and higher earners (not so good!). In other words, it’s costly to be a graduate in the middle of the earnings distribution, particularly for middle-to-higher earning women.

Policy implications

There are many challenges associated with the current fees and funding regime – but importantly, tinkering with the system might cause even more problems. Reducing the interest rate charged is costly – and disproportionately positively impacts those with above-average graduate earnings (who repay early and part-subsidise the lowest earners). Unfreezing the repayment threshold would benefit lower earners. Extending the repayment period would extend the burden for middle earners for even longer.

Reducing the rate of repayment might marginally benefit middle earners at the expense of top-earning graduates. However, any of these approaches would require years to implement (as witnessed during the Diamond Review in Wales) and would only put even more sticking plaster on a system that is already freakishly complex.

A system where tinkering makes it worse? Surely it should be abolished then. And why are we using exactly a usurious interest rate to cross subsidise students in a year group by the highest earners in that year group? Surely only to have something to sell to the finance industry afterwards. If there should be a cross subsidy it should be by all taxpayers. Anyway, the system is comprehensively crap. And the earlier it is abolished, the better. The fact that it might not be progressive because high earners repay a usurious loan earlier is just one of the many… Read more »

One solution is for the government to evaluate how best to lower the repayment threshold and the interest rate. And tell HEIs to stop teaching courses with zero employability or lose funding.