For a document released in 2011, the Students at the Heart of the System white paper is having an unexpected late moment in the sun right now.

It’s where you’ll find the initial request that UCAS publish data showing the type, subject, and level of qualifications held by successful applicants to specific courses. Something that was announced by UCAS only last week.

And it is where you will find the routes of another long and painful data tale that has a very contemporary feel – Data Futures.

We will ask the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), and the Higher Education Better Regulation Group (HEBRG), in collaboration with the Information Standards Board for Education (ISB), to redesign the information landscape for higher education in order to arrive at a new system that meets the needs of a wider group of users; reduces the duplication that currently exists, and results in timelier and more relevant data.

A history of the future of higher education data

That recommendation, tucked away in chapter 6 (para 6.22, no less), led initially to the bodies in question commissioning Deloitte to produce an initial proposal for collecting and sharing sector data. This led to an independent exploratory program, running from 2013 to 2016 – the Higher Education Data and Information Improvement Programme (or HEDIIP).

HEDIIP is an acronym that makes a generation of higher education data professionals get all misty around the eyes. Almost universally loved, it carefully and consensually developed with the sector and key stakeholders a range of work packages around key data themes:

- Data capability – helping organisations get better at managing their data

- HE data language – a student data model, with associated definitions

- Subject coding – the genesis of HECoS and CAH

- Student identifiers – work on the adoption of the ULN in higher education

- Inventory – a surprisingly long list of all the existing higher education data collections

- New landscape – all-encompassing work on the wider higher education data landscape, commissioned from KPMG.

At the time, the key recommendations came from the “new landscape” work. Though the end of programme report rightly highlights successes in all of the project areas, only the subject coding work and the HESA data capability toolkit have led to lasting change.

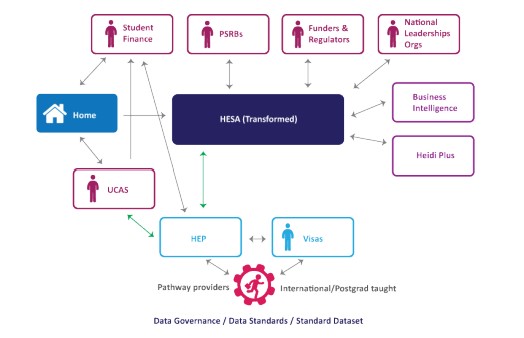

The other parts of HEDIIP work were swallowed into Data Futures. Most notably, this included the idea of HESA as a data warehouse, which would allow other data collecting organisations the ability to draw from a common dataset rather than perpetuating the “shocking” amount of data duplications (97 different collectors, 520 different returns).

The “official” programme kicked off in 2016 with grants from the four UK higher education funding bodies totalling £7.4m. It initially contracted with Civica in 2017 as a part of the detailed design phase – with the advice given at the bidding stage for that contract emphasising the role of HESA as a central collector and distributor of sector data, involving new, speeded up, collections alongside greater efficiencies. The bit that made the sector sit up and pay attention was the idea of multiple, in-year, submission points for data (up to 7 in one indicative diagram) – replacing the deadlines towards the end of the calendar year that had existed, at that point, for more than two decades. But of equal importance (and the subject of attention within data specialist circles) was a redesign of the data model – which would determine what data is collected and how it is structured.

The initial plan was for a full pilot in 2018-19, freezing the specification by August 2017 so providers could prepare and tweak internal systems as required.

What happened next?

Well, history relates that we finally achieved (for various values of the word achieved) a single deadline collection using the new Data Futures data model for the 2022-23 academic year. Though it worked – in the sense that some data was collected – the experience was a painful one. Although any change in a data collection will yield a momentary drop in data quality, numerous issues with the data collection platform (in particular the application of data rules) have led to problems. As things stand, providers had the chance to update their submissions through to April 2024, and following a final round of checks and consultation from the Office for Students, we expect to see data land in August 2024.

Not to discount the many hours of hard work by those involved, this is a little bit of a departure from the schedule.

Initially things seemed to be working out OK – version 3 of the collection design dropped in February 2017, and the programme moved into the detailed design phases. In August HESA’s Rob Philpotts was in an upbeat mood as the design phase came to an end, promising the publication of the 2019-20 student record specification in the coming weeks. By 2018 people who provide technology to higher education institutions were getting excited about implementing it. The Alpha phase launched in January 2018, by March some 14 providers were involved. A Beta phase covered 2018-19.

But it turned out not to be that easy.

Data despair

The redoubtable Student Record Officer Conference (SROC) held a one-off day in November 2018. Those who were there will recall “The Wall”, 249 post-it notes detailing the concerns of sector professionals around the design and delivery of Data Futures. March 2019 brought confirmation that Data Futures would not be going live in 2019-20, so that year was collected using what I guess we should call HESA Student “classic”. Even a cursory glance at September 2019’s OfS Board papers suggested that toys had very much been thrown out of the pram:

HESA Data Futures continues to face significant delivery issues which impact onward delivery to OfS. It has now been confirmed that HESA will not be able to deliver in-year data until 2021-22 at the earliest and there are still considerable questions about its ability to deliver for 2022-23. We have ceased grant funding for Data Futures until a clear way forward has been identified.

November saw a decision (with “complex” ramifications) to move to discrete collections, with three reference periods. January 2020 saw the Board return to the topic, in a paper so secret it remains redacted more than four years on. It is not hard to guess that it discussed the way Jisc replaced Civica as the technical delivery partner for Data Futures. This announcement was made quietly by HESA on 18 February 2020:

HESA has decided to deliver the next phase of the programme using an alternative delivery approach.

Another review

As OfS board papers relate, by the Covid-scarred September of 2020 HESA and Jisc (as data collection mechanism partner) were moving things forward – this kicked off with £1m for Jisc and £1.3m for HESA, then a further £2.6m was chucked into the pot to cover things until March 2021, with a further £7.2m (including a £1.1m contingency) for work between April 2021 and March 2024.

In retrospect this is a fascinating paper. There was a KPMG review of governance (annex C) that suggested it was not clear what the “nature and extent” of the OfS role in the programme was. The initial specification gave our beloved regulator involvement in “key design decisions” and demanded that progress should be “tracked against OfS requirements” – however it did not clarify what a key decision was or what OfS requirements were. An explicit recommendation to sort this by properly documenting things was merrily rejected.

It established a quarterly review group that would report to the OfS board (with funding tied to satisfactory reports), but failed to give the appropriate bits of OfS capacity to properly monitor progress – just two people had oversight of the programme, on top of substantial other roles.

The paper also states bluntly that OfS “requires” three data collections a year, something that becomes funnier in retrospect.

God bless us, every one

The new Alpha phase of the programme, involving piloting systems with a limited number of providers, ran between May 2021 and January 2022. In December 2021 a Christmas Carol themed blog announced a consultation on yet another change to plans from the Office for Students – with the idea of three individualised collections dropped. The options on the table were two collections, a cumulative three part collection, or a single collection with a shift to timing from the sacred norms.

Responses to this collection turned up in two chunks: part 1 (which confirmed a move to two collections by 2024-25, and suggested a potential removal of the HESES collection altogether!) in May 2022, and parts 2 and 3 (which deferred decisions on the removal of data items and the use of linked and third party data to “the short to medium term” ) in November 2022.

The Beta phase of the programme ran between February 2022 and November 2022, helped by the release of the online validation toolkit in June. By August, everyone was collecting using the new model ahead of the 2022-23 collection. And in October 2022, Jisc and HESA completed their long rumoured merger – which, little noticed at the time, brought an end to OfS funding for Data Futures.

Extended play

With the agreement of statutory customers, the sign off and final submission deadlines were extended in August 2023 (by two weeks), again by a further week in mid-October, with a later decision to collect information about provider concerns about submissions. This latter communication came on the same day as a decision by OfS not to attempt in-year data collection for 2024-25, which also communicated knock-on delays to HESES and Graduate Outcomes data collection plans.

It is from here that we got the idea of an independent review of data futures – something that more than 6 months on does not have a chair, terms of reference, or expected start date. Jisc has already run and drawn conclusions from an internal review that will feed into the 2023-24 collection already in active development. Providers have been asked not to expect all of their concerns to have been addressed. And the 2022-23 Student open data release (as confirmed by HESA in April 2024) is also 6 months late – arriving, we hope, in August 2024.

March 2024 brought another note from the Office for Students, bumping in-year data submissions to 2026-27 at the earliest, while promising to share details of the review in “the coming weeks”. It has not yet happened, and all I have from OfS is a personal assurance that a potential supplier has been selected (nothing on a chair or terms of reference) with due diligence underway.

Now what?

Twenty-twelve is a long way behind us, but we do not feel significantly nearer to the dream of a free flow of real-time student data. It will be 2026-27 before we even get more than one submission a year. And the current plan of two doesn’t exactly make for a finger on the pulse of the sector. The enormous delays to the programme have led to an unfortunate clash with the birth of the lifelong learning entitlement, at which point regulatory plans and thus data needs will change again.

The 2022-23 collection – a single deadline – looks, from the outside, very much like what has been standard HESA practice over the last few years. But even the avowed endpoint (an individualised in-year collection with multiple submission points) simply duplicates the HESA process between 1994 and 2001. Higher education providers already submit monthly data as part of the arrangements for apprenticeship funding. Data Futures as things stand currently is very much behind the curve. And it keeps changing, without offering many of the benefits that change could bring. A lot of very experienced data professionals have left the sector in frustration, and they will be very hard to replace.

We’re edging towards the end of the decade before we are likely to see two sets of data collected under the same (or broadly similar) specifications – with a consequent detriment both to data quality and the value of time series within the HESA Student data. This is not to downplay the hard work that staff at Jisc and providers put in last year and this year, but it is a shame and it does the sector no favours in government. The issue of data burden continues to be raised – with a focus on the needs of one statutory customer meaning that the idea of wider applicability, and a single data collection driving multiple analyses for multiple customers, appears to have been largely abandoned.

A proper independent report will help in establishing just what can be learned from this entire debacle. All we need to do now is launch it.

One of the unfortunate outcomes of the whole 22/23 Data Futures fiasco is that a lot of people have ended up holding the DF data in tables on their system that are separate from their main data. Whilst this has always been the way that many systems work, what almost certainly happened in 22/23 was that more data was manually updated in these HESA tables to get returns through. There is then a greater difference between the HESA data and the data that the institution is using to manage its students, which raises issues with internal reporting and comparisons to… Read more »

I suspect issues may arise because providers have become increasingly dependent on HESA to generate what they consider ‘management information’, but relatively little is based on internally generated data (e.g. processing). It’s only return compilers who have to cobble that together into a ‘valid’ return, for HESA to enrich and provide to data customers, to populate their data warehouses and dashboards. I suggested HESA share their derived data after introduction of the old Student Return in 2007/8, and ‘HESA Core Data’ has been provided since 2008/9. That made the Student Return an annual source of validated and enriched data for… Read more »

Don’t be told what you want

Don’t be told what you need

There’s no (data) future…