Just before midnight on Wednesday, November 13, 2025, Paula Karhunen faced a room full of journalists.

Her unenviable task was to explain how and why Helsingin Yliopiston Ylioppilaskunta (HYY), widely regarded as the world’s richest students’ union, had just voted to sell almost everything it owned.

Karhunen is HYY’s pääsihteeri – Secretary General – the most senior professional staff member who leads the organisation’s day-to-day operations while the democratically-elected Board and Representative Council set policy.

A social sciences student not so long ago, she’d been active in Green youth politics for years, had served on the University of Helsinki’s SU Board in 2019, and on the board of SYL (the National Union of University Students in Finland) in 2020.

When HYY’s previous secretary general departed in autumn 2024, the Representative Council appointed her to step into the role – initially on a temporary basis, later extended through December 2025 as a crisis deepened.

As midnight approached on the 13th, she’d spent the previous hours in a marathon meeting that had stretched past five hours. At one point, a fuse had symbolically blown in the meeting room.

The 60 student representatives present had heard briefings on the financial situation, emotional speeches from political factions, and ultimately voted unanimously to approve the unthinkable – selling the Vanha Ylioppilastalo (Old Student House), the Uusi Ylioppilastalo (New Student House), and almost all of HYY’s prime Helsinki property holdings to Keva – Finland’s largest public sector pension insurer – for approximately 187.7 million euros, roughly 100 million euros below their assessed value just a year earlier.

Karhunen chose her words carefully:

Parting with Uusi and Vanha ylioppilastalo is a historic and difficult decision, from which one may also feel sorrow. However, as a result of this decision, we can continue to use all membership fee income solely for student activities, and we finally have a view to the future. HYY’s operations can change, as they have changed numerous times in history, but the student union will survive.

The next morning, she elaborated in a blog post that attempted to name what had been sold:

The student houses have been a place for culture, a home away from home, for being together, for celebrating under the rain, and have offered students a free third space to just be. Some alumni have certainly woken up this morning shocked after the news confirmed last night.

Then came a metaphor for what Helsinki’s students had lost:

I’m not saying this because it’s not okay to say that it’s like grieving for a block-sized elephant that’s flattened under 150 years.

A block-sized elephant, 150 years old, now flattened. That image captures something essential about HYY’s story – not just the scale of what was lost, but the weight of history behind it, and the crushing nature of how it ended.

Yet the story being told in the aftermath threatens to become dangerously simplified – naive students play property developer, make risky decisions through messy democratic processes, and lose everything through incompetence. Democracy, the story goes, simply cannot handle serious business decisions.

The actual story is far more complex – and far more important. Because what happened to HYY wasn’t really a failure of democracy. And what remains represents something extraordinary – a student republic that has shaped Finnish political culture for 157 years, survived civil war and financial catastrophe, and continues to operate both radically and creatively at a scale that makes it viscerally impressive.

This is that story.

The homeland gave to its hopes

To understand what HYY represents, we need to understand what it built from the beginning. And that story begins not in Helsinki per se, but in marshland.

When the Great Fire of Turku destroyed much of that city in 1827, Emperor Nicholas I ordered Finland’s university to relocate to Helsinki. At the time the capital was a small, undeveloped settlement, and Finland itself was “almost one-third covered by bogs, fens, peatlands, and other swamplands.” Building a university in Helsinki was an act of faith in creating something grand from unpromising terrain.

The university’s main building was completed in 1832, designed by Carl Ludvig Engel, a German architect famous for rebuilding Helsinki and designing many of its key public buildings in a Neoclassical style.

But students lacked their own space. The push came from J.V. Snellman, a philosopher and statesman appointed in 1856 to oversee and guide students. His vision was a building to unite all student activities under one roof, creating a forum for political and philosophical discourse that would shape the nation.

In 1868, Emperor Alexander II issued a decree formalising student assemblies, and HYY was officially born. Originally called “Suomen ylioppilaskunta” (Finland’s Student Union) until 1928, it started as a cooperation body for the ancient student nations – regional associations that remain some of Finland’s oldest organisations.

The Old Student House opened on November 26, 1870, after a fundraising campaign that mobilised citizens across Finland. The building’s facade bore a Latin inscription that would define HYY’s identity for the next century and a half:

Spei suae patria dedit/The homeland gave to its hopes.

In turn, students became “Spes Patriae” – the hope of the nation.

The opening celebration was legendary. It began with Mendelssohn’s march and “Maamme,” continuing until four in the morning, with guests consuming 463 bottles of beer, 25 bottles of cognac, and 75 large carafes of Swedish punch. Helpfully, the building was deliberately sited at the city’s edge so that student revelry of that sort wouldn’t disturb other citizens. Within decades, Helsinki would grow around it – placing it at the heart of the capital.

Otto Donner, a law student who became the student union’s first chairman in 1868, captured the spirit in his inaugural speech – students would become “national influencers, new great men.” The building itself became a pantheon, filled with portraits of Finnish luminaries whose work had shaped the nation. Anders Johan Porthan, the 18th century historian and “father of Finnish historiography,” hung alongside J.V. Snellman, whose philosophical writings in the 1840s-50s had championed Finnish language and culture under Russian rule.

Elias Lönnrot’s portrait honoured the man who had compiled the Kalevala – Finland’s national epic – from oral folk poetry in the 1830s-40s. Walter Runeberg’s sculptures adorned the halls, while Akseli Gallen-Kallela – the symbolist painter who became Finland’s most celebrated visual artist – created Kalevala-themed murals including his famous “Kullervo Rides to War.”

Imperial decree was one thing – but HYY’s real wealth came from something more prosaic – cheap land. In the late 1800s, Helsinki’s city government sold HYY several plots for nominal sums. As one historical account notes, “when Vanha ylioppilastalo was built, the plot was quite extensive and located at the city’s edge.” Over the next century, as Helsinki expanded, those peripheral plots became prime real estate in the capital’s core.

By the 1990s, as one journalist put it:

If you walk from the Railway Station through Kaivopihan toward Stockmann, you’re practically walking on student-owned land.

Building the student state

What HYY did with that wealth was remarkable. It didn’t just accumulate assets – it built infrastructure that pioneered models copied across Finnish higher education and beyond.

In 1858, the Student Library was founded by merging the collections of student nations. It operated as HYY’s library until 1974, when it transferred to university control.

By 1910, Vanha was no longer sufficient for Helsinki’s growing student population. A design competition held in 1908 was won by architects Armas Lindgren and Wivi Lönn – notably, Lönn was one of Finland’s first prominent female architects. The Uusi ylioppilastalo (New Student House), originally named Osakuntatalo (House of Nations), was completed in 1910.

Built with Finnish and Norwegian granite exteriors and Italian marble interiors, it housed the offices of the student nations – by then, young people from fifteen countries were studying at the university. In 1924, the building grew by two more floors and gained lifts, heating and hot water supply.

Like Vanha, it funded its maintenance through commercial tenancies – Hotel Hansa operated there from 1924 to 1968, a cinema opened in 1929, and a car dealership in 1930. The building became both student space and commercial hub, prefiguring the mixed-use model that would eventually prove so fateful.

In 1913, Ylioppilaslehti – the student newspaper that remains one of Finland’s most respected independent publications – began publishing, becoming a crucial voice in student politics and national debate.

The journey toward student health began in 1932 with tuberculosis screening. After a health office opened in Helsinki in 1946, the Finnish Student Health Service (YTHS) was formally founded there in 1954. As Kari Rahiala, SYL’s (Finland’s NUS) head secretary, later reflected:

For my age group, who did not create it, but enjoyed its benefits, the creation of university student health services was overwhelmingly the most important achievement.

Dental care launched in 1955, mental health services in 1969, and a dedicated Ylioppilaiden terveystalo building opened in 1971.

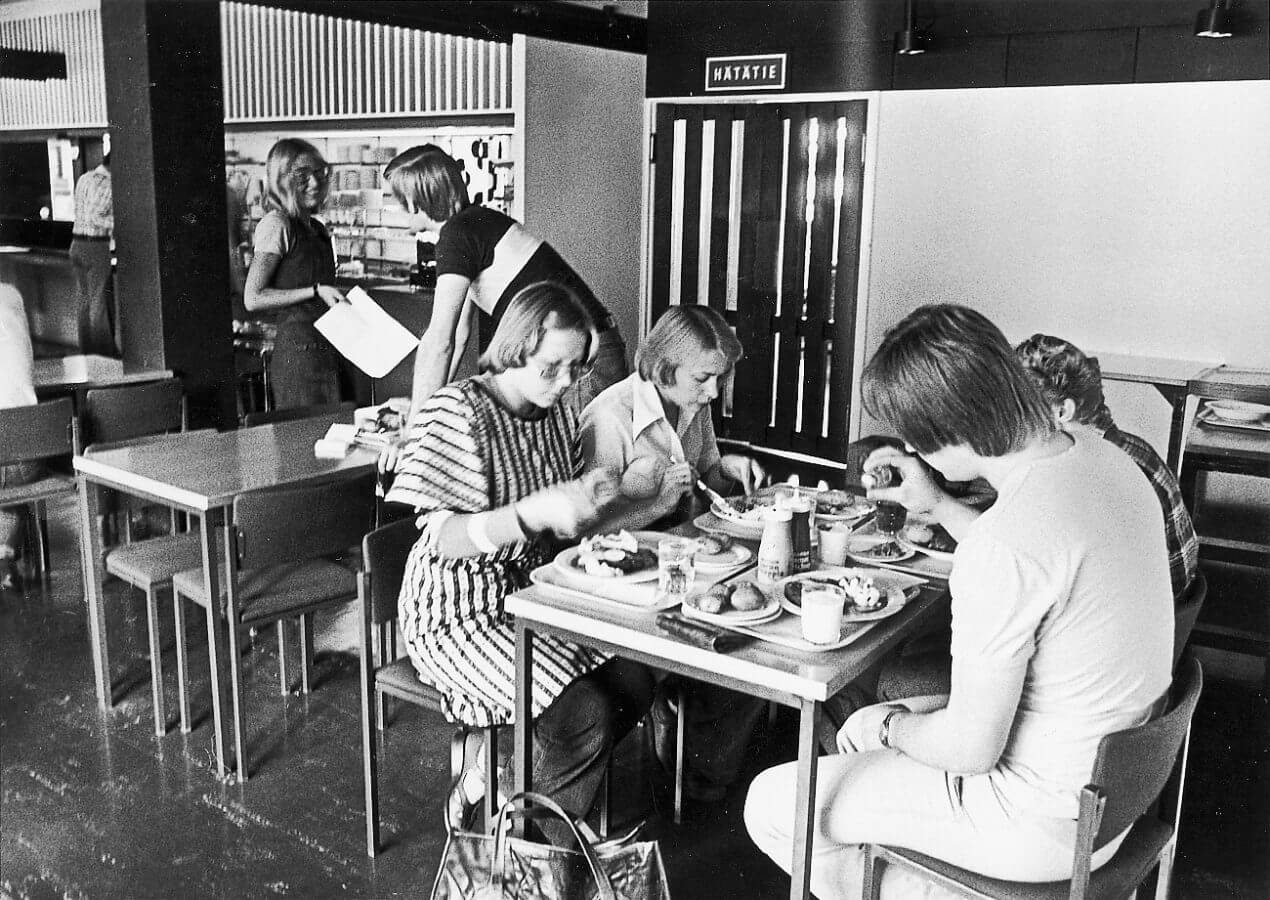

In 1953, HYY began establishing student canteens, which evolved into the UniCafe chain – providing subsidised meals across campus, entirely student-owned through HYY’s commercial subsidiary. To this day, even in one of the most expensive cities to be a tourist in in the world, it’s cheaper to get a hot meal in a UniCafe than in a Chartwells or Sodexho outlet in the UK.

Over the decades, it was less charity, more nation-building. HYY was creating parallel structures that would provide for students independently of state or university control, funded by property wealth and student fees. The model was unique – a democratically-controlled corporation with both commercial interests and public duties, possessing real autonomy guaranteed by law.

By 1994, a visiting American journalist marvelled that HYY was “the richest student union in the West, if not in the world” – they’d checked, and found only the University of Abu Dhabi had more wealth. By 1998, Tapio Kiiskinen, HYY Group’s president and a business executive who had worked with the student union for over 28 years, was running what the International Herald Tribune called “one of Finland’s most successful medium-sized businesses” with more than 600 staff and forecast sales of $205.8 million.

Kiiskinen described HYY as operating like “an informal business school” or “a branch of the university in the science of life” for students whose preoccupations ranged “from Kierkegaard to calculus.”

HYY subsidiary Kilroy Travels had become Europe’s largest youth travel agency, with operations across seven countries. Its book division published literature in humanities, social sciences, and current affairs. Property holdings included 44,000 square metres in central Helsinki. Forty per cent of dues revenue funded health care, and about half of HYY’s annual budget supported smaller student organisations.

As Anja Kosonen, HYY’s official spokesperson in the 1990s, put it:

It’s an indescribable feeling to sit on the Student House balcony in the early hours of the morning after a successful event, sipping a little wine and looking at Helsinki from the heart of the city. You feel there’s something out there in the world – and that we are already contributing to it.

Revolution in HYY or death

The political significance of it all can’t be overstated. From 19th century nationalist movements through the New Left in the 1960s to the present, HYY seems to have been at the centre of politics.

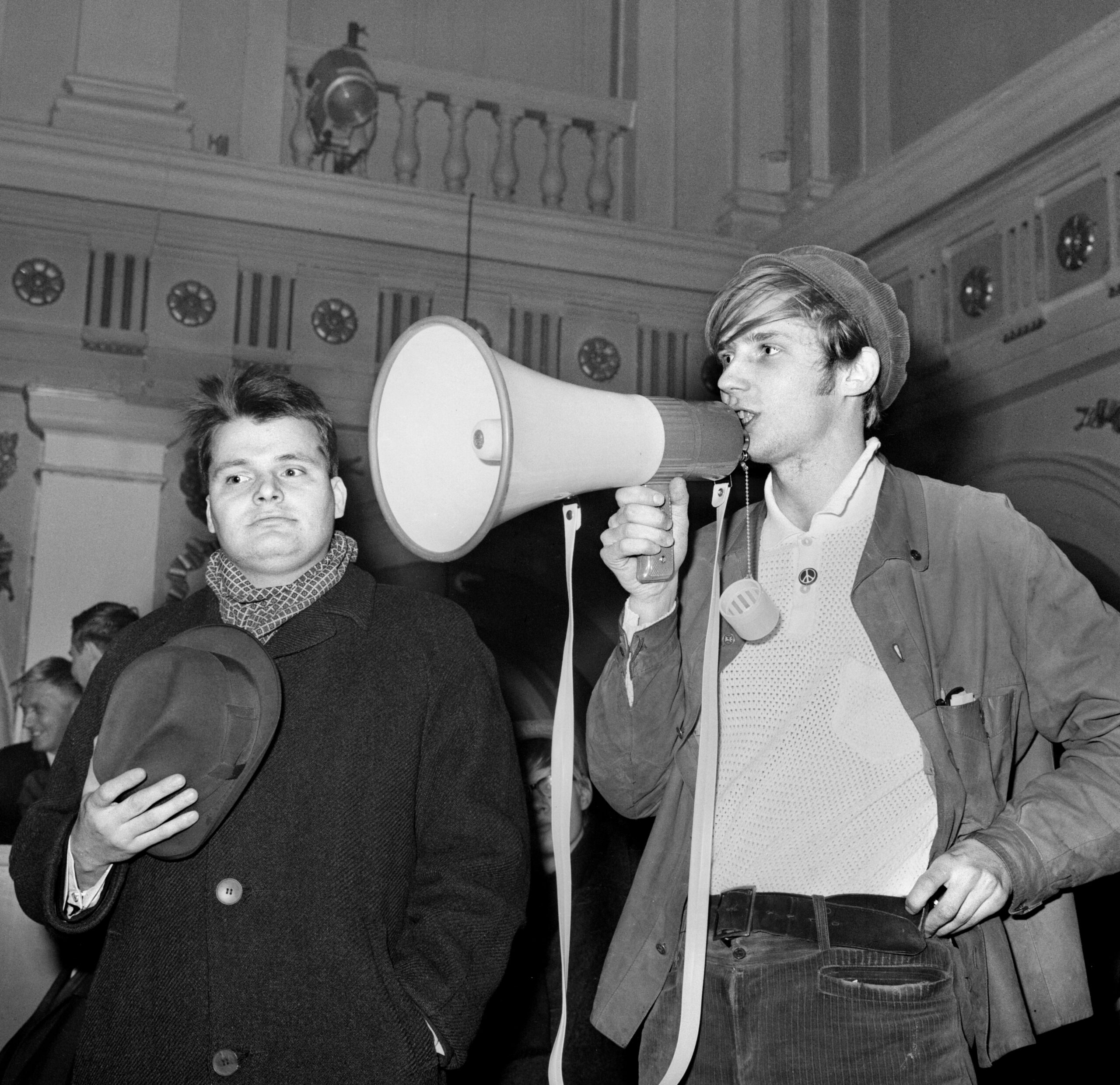

A defining moment came on November 25, 1968, the eve of HYY’s 100th anniversary celebrations. A group calling themselves “Ylioppilaat – Studenterna” occupied the Old Student House at 5:13 PM, demanding democratic reforms to university administration, Marxist-Leninist study circles, abolition of compulsory union membership, and changes to Ylioppilaslehti’s political line.

Riitta Suominen, a sociology student who served on HYY’s board in the late 1960s, captured the elitist atmosphere protesters were rebelling against:

HYY’s atmosphere with its grand festivities and the addressing each other as “Miss” and “Mister” brought to mind an estate society.

Kimmo Rentola, now a professor of political history at Helsinki University who has extensively researched the period, tells the story of the occupation’s beginning:

There are many versions of events, but according to one, the occupation almost didn’t happen because the door was locked. Finally one window broke and a Student Theatre actor also came to open the door.

Inside, a banner proclaimed:

Revolution in HYY or death.

Risto Alapuro, then working as an assistant at the sociology department and now a professor of sociology, recalls:

In the great hall, speeches given via megaphone took stands on the Vietnam War and other great questions of the time. In smaller rooms there were working groups.

The drama intensified when right-wing students opposing the occupation threw smoke bombs into the hall from the galleries. Risto Volanen, a Centre Party activist who was one of HYY’s young activists in 1968, remembers:

I too thought it was a fire. I grabbed a fire extinguisher and started heading toward the smoke. Someone had the sense to start shouting, stay where you are.

Volanen stayed at Vanha overnight and slept wrapped in his coat. Protesters sent a telegram to President Urho Kekkonen asking him to skip the centenary celebration. And when Kekkonen attended the rescheduled event at the Conservatory, he expressed support for the occupiers:

The rebelling groups don’t seem satisfied with small concessions or minor improvements, but demand a deep systemic change and transformation of lifestyle. Open-mindedly thinking youth is the future’s ideological bomb. That is the world’s hope.

Prime Minister Mauno Koivisto dismissed the movement as “nuorten ilmavaivoiksi” – “youth flatulence.” Yet as political scientist Jukka Tarkka observed, the Vanha takeover was a watershed in Finnish student movement history – it ended radicalism’s “happy hippie” phase and was a leap into the new decade.

The occupation ended peacefully when the occupiers – who knew student groups were keen to get back in – cleaned the building, before going home at 17:13 on November 26.

The political training ground

Infrastructure like this builds ideas, confidence, and ambition – and over the years, HYY has been one of Finland’s most important political training grounds. As Laura Kolbe, professor of European history at Helsinki University and one of Finland’s leading historians of student culture, has observed:

HYY’s Representative Council name lists have for nearly two centuries revealed who will rise to ministerial posts, city councils, senior civil service positions and international leadership roles. This connection hasn’t changed over time.

The 1968 occupation alone produced a generation of political leaders. Erkki Tuomioja, a law student who participated in the occupation and spoke via megaphone from Vanha’s stage, entered parliament in the 1970 elections and served as Finland’s foreign minister from 2000 to 2007 and 2011 to 2015 – Finland’s longest-serving foreign minister. Risto Volanen later became state secretary – the most senior civil service position in Finnish ministries – under Prime Ministers Matti Vanhanen and Anneli Jäätteenmäki.

Plenty of others from that generation secured prominent positions across Finnish society. In 1975, Tuomioja even dated Tarja Halonen, who later became Finland’s president.

The pattern continues now. HYY’s democratic structures – a 60-member Representative Council elected every two years, with multiple political groups running serious campaigns – provide genuine parliamentary experience. The 2024 elections had 374 candidates competing for 60 seats, with 8,669 people voting from 26,825 eligible members. Most candidates go on to find themselves in civil society, government and business – taking the ethics and concern for others into the “real world”.

Students learn political rhetoric, cooperation, and decision-making on issues with real stakes – budgets worth millions, representation in university governance, and policies affecting 27,000 students. The country and its politics are better for it.

The cultural crucible

As well as generating activists, having your own space allows you to change the rules. In the decades after 1968, Vanha became more than a political space – it became a cultural crucible where Finnish progressive culture was forged.

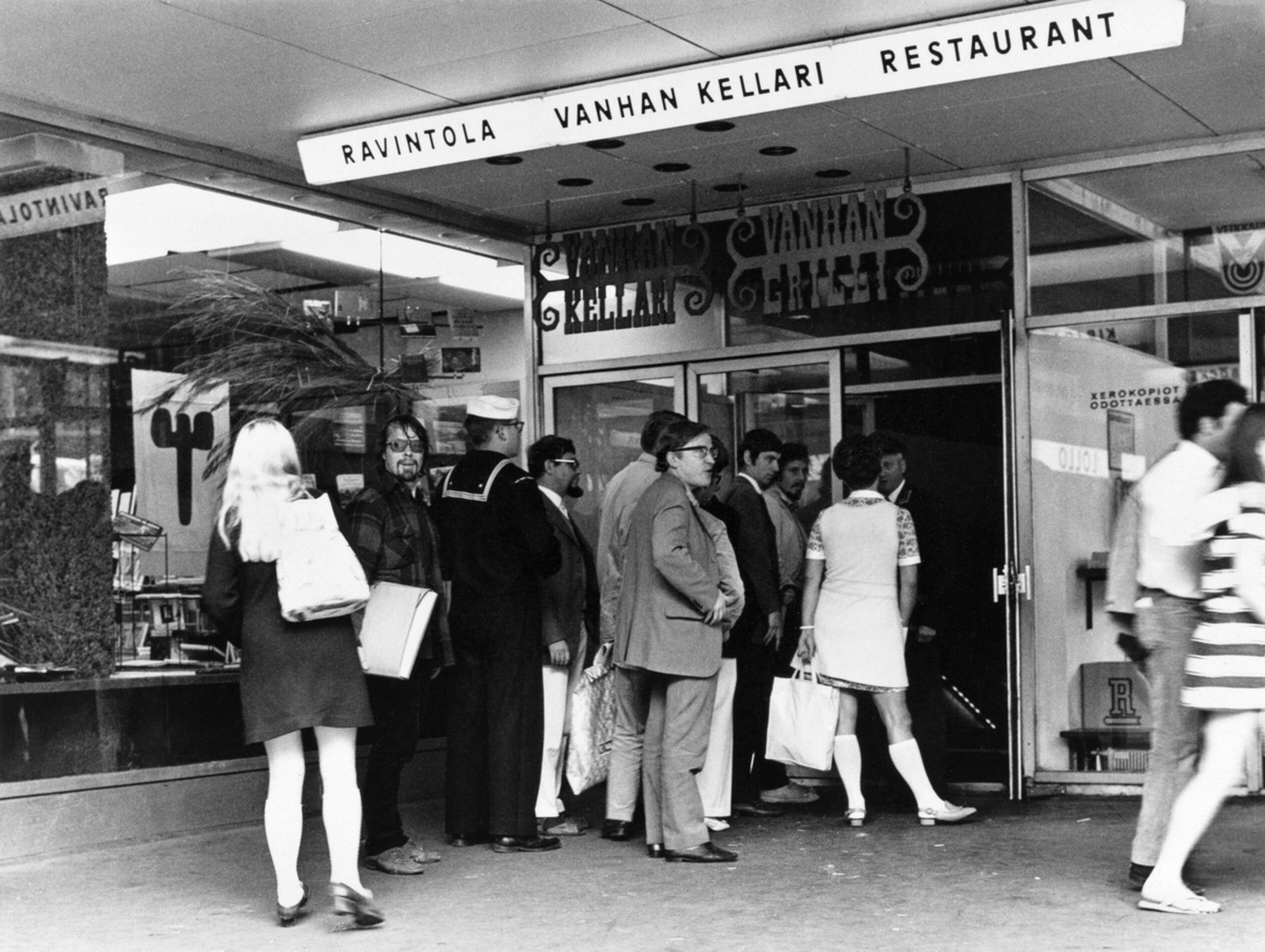

In November 1964, Vanhan Kellari restaurant opened in the Old Student House basement. Homosexual men, tired of furtive flirtation in straight venues, claimed it as their own space almost as soon as it opened. At the turn of the 70s, lesbian women took over the Karhukabinetti within the basement, creating Finland’s first lesbian bar.

After the occupation, a Cultural Centre was founded in 1969. Asko Mäkelä, a musician and cultural organiser who worked extensively with the Cultural Centre, remembers:

This was actually the place where art university students met for the first time. Here were joint exhibitions and activities from all art universities. There were no fences. For example, jazz and rock musicians did things together. From that was born the heart of Finnish prog, Wigwam and others.

Outi Popp, another key figure in the Cultural Centre who later became a cultural historian, recalls the booking strategy:

In the 1970s Kaisa Korhonen and Agit Prop always packed the place. And when you have a room full of beer-drinking people, of course they got booked. And they were booked for Mondays, because otherwise there wouldn’t have been any events then. Weekends were devoted to jazz and rock.

Dave Lindholm, who became one of Finland’s most beloved blues and rock musicians, started there at just 16 years old. Vanha was where conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen, composer Kaija Saariaho and singer Arja Saijonmaa began their careers.

In the early 1970s, the New Student House was hit with a liquor raid. Political student organisations dominated the “party front” until the waltz club Kannunvalajat set up Kannu-klubi:

There the blues played and beer flowed. Word spread so widely that not all who wanted could fit in to jam.

Police intervened again with a raid due to suspected drug use around the club. After years of legal proceedings, Kannunvalajat’s board was sentenced to pay substantial fines and damages. Nevertheless, parties continuing until morning were popular after-party spots until the end of the 1980s.

Students running the Cultural Centre organised the city’s first free, open-to-all park concerts, and generations later, students launched “World Student Capital” – a vision for a city with education at its heart which would benefit both those in education and its wider residents.

What HYY still does

Of course buildings are, in some ways, just buildings. But as I say, when students hang out in buildings of their own, remarkable things happen both in them and across the cities they’re in.

Today the Grand Sitsit gathers around 2,000 students on Senate Square for outdoor academic dinner parties, with over 100 student organisations each running their own tables with three-course meals, traditional songs performed in Finnish, Swedish, English, German, Estonian and Latin, attended by the University Board Chair, former President Tarja Halonen, and city officials.

The Opening Carnival lets new and returning students explore 250-plus organisations operating under HYY. The Fresher Adventure – billed as “Finland’s biggest event for new students” – reinvents the pub crawl to take over Helsinki streets with teams completing checkpoint challenges organised by HYY, student organisations, the university and partners – building belonging for the 7,000 participants along the way.

HYY members get free legal assistance from student volunteers, Little HYY provides temporary childcare for student parents during lectures, exams, or health visits, and the traditional annual Independence Day torchlight procession lights up the city streets while honouring those who fell in the Civil War.

Students have seats on the Academic Affairs Council (led by vice rector, preparing rector’s decisions on teaching policy), Scientific Council (research policy), Societal Interaction Council, plus faculty councils across all 11 faculties, following the “tripartite principle” where university bodies include academics, other staff, and students.

HYY has dedicated educational policy specialists who sit on key councils alongside the elected student representatives. Faculty-specific selection committees of three-plus students process applications for student representative positions, with dedicated selection coordinators and training for representatives. Student representatives receive meeting fees, can earn university credits for representation work, get free annual training on communication and influencing, and can request certificates of service.

This student life sim game was invented there. They got university officials, politicians and civil servants to play it so they better understood the realities of student life. Student finance improved.

Hundreds of students serve on university committees and working groups via the Halloped website, encouraging diverse applications from different genders, study stages, and backgrounds.

Student tutors play a vital role in welcoming new students, helping them integrate into the university community, and offering guidance alongside university staff.

And its sustainable development projects include a development cooperation project in Mozambique, which supports the education of girls and young people with special needs, and a joint project with the Union of Finnish SUs (SYL) that encourages responsible consumption.

When Jari Eerola retired in 2020 after 33 years as HYY’s archivist – the SU’s longest-serving employee – he reflected on what had united people across HYY’s history:

The joy of working together and a belief in dreams and the power of spoken word have united the people of HYY throughout history. The young people who have been involved in the Student Union are an excellent example of creativity: great things have been accomplished even with meagre resources.

That creativity, that capacity to accomplish great things with limited resources, would soon be tested like never before.

The dream

In spring 2015, 29-year-old Antti Kerppola was preparing to move to Oslo. He’d served on Ylva’s board as a student representative and as board chair after graduating in law. Then Ylva’s board tipped him off – the CEO position was opening. Oslo could wait.

Kerppola describes his approach as CEO as “brash” (räväkäs). He saw urgent need for change:

HYY’s wealth had developed poorly and properties had been allowed to deteriorate. There was perhaps too much staff and results were burdened by management’s relatively high salaries. Kaivopihan’s rent levels lagged and it was filled with bars, a gambling den, and a pharmacy.

He implemented a “100-day plan” – sell the Gaudeamus publishing house, and close 13 unprofitable UniCafe restaurants immediately that first autumn.

I wanted to clear the table and ensure that things I’d promised would happen. I had a strong mandate and momentum to do things.

Student representatives remember Kerppola – nicknamed “Kerppis” – as uniquely engaged. “His background in student organisations gave him a special ability to understand students’ perspective,” multiple interviewees told Ylioppilaslehti. He responded to individual representatives’ emails personally – rare for a CEO.

Having delivered turnaround, Kerppola and his student led board looked to the future – and a goal crystallised – eliminate membership fees by 2025. This wasn’t unprecedented – students involved in HYY had long dreamed of leveraging its property wealth to free students from fees. But making it official changed everything.

At the time, students paid 103 euros annually, including 54 euros to the Student Health Service. HYY wanted to zero out its portion – then 49 euros – while maintaining services. The only way to achieve this without massive cuts was to double or triple Ylva’s returns.

The logic seemed sound. Interest rates across Europe had been at historic lows for years. International investors were flooding into Finnish property. As Lauri Linna, who served as HYY Board Chair in 2018, would later reflect:

It’s based on the idea that HYY Yhtymä can produce such good results that membership fees can be abandoned through that.

The 60-member Representative Council and annual rotating boards all bought in. The 2018 board’s Facebook group was nicknamed “MYA” – Merkittävät Yhteiskunnalliset Avaukset (Significant Social Interventions). The name was ironic, lifted from strategy papers discussing the 150-year-old union’s societal significance. But the ambition was real – developing “the Helsinki of the day after tomorrow.”

In 2016-2017, Helsinki announced a plot competition for Siltasaarenportti – a prominent waterfront development site in Hakaniemi, a central district just northeast of Helsinki’s city center. Ylva prepared an ambitious bid for this gateway location – the Lyyra Block, a mixed-use development combining hotel, offices, and housing. In June 2018, they won. For Kerppola, this victory in one of Helsinki’s most strategically important redevelopment areas stands as his greatest personal achievement:

There was tough competition for the plot, which Lyyra ultimately won on quality, not money.

When they presented the bid to HYY’s Representative Council in Helsinki University’s ceremonial hall – complete with a Gangnam Style-enhanced promotional video – “the representative council rose to its feet in applause,” Kerppola recalls.

Then, mid-competition, another opportunity emerged. The Kalevan talo – a historic building in central Helsinki known as Hotel Seurahuone – suddenly came on the market when its owner Sponda, a major Finnish property investment company, was sold to foreign owners.

Multiple interviewees say HYY, the Student Union of the University of Helsinki, had long coveted the building as a natural extension of their Kaivopihan holdings – existing student union properties in the Kaisaniemi area of central Helsinki. “There was a strong desire in the community to buy, and we knew this was the momentum to make history,” one source recalls.

The vision was to create a “Student Quarter” (Ylioppilaskortteli) – consolidating multiple properties into a unified student hub in the heart of Helsinki’s city center.

It wasn’t as if HYY hadn’t done it before. In the 60s, it was the lead organisation in the creation of HOAS, where students gathered a small amount of capital and took out a hefty bank loan to create their own Foundation for Student Housing. It’s now a business with a turnover of 80 million euro and 11 000 student apartments.

Negotiations over the Student Quarter began in the summer of 2018, initially within Ylva’s management and board, plus HYY Board’s working committee (chair, vice-chair, and chairs of the finance committee and Ylva’s supervisory board). For larger investments worth multiple millions, HYY’s board needed to approve.

On the day of signing, Board Chair Lauri Linna recalls Kerppola joking:

Have you bought your first apartment yet? Well, now you’ve started with a rather larger purchase.

Representatives celebrated that HYY finally owned the legendary Milliklupi nightclub in the building.

The plan was to merge Seurahuone with parts of New Student House’s B and C stairwells to create a 240-room luxury hotel. Kerppola promised “elämyksellisyyttä” (experiential qualities) and responsibility. As he told the media in 2019:

We want the hotel to breathe contemporary luxury: experiential quality and responsibility.

The hotel conversion was not without controversy – it would force students to give up some of their spaces for commercial development. Jane Kärnä, who served as organisation liaison on the 2018 board, recalls this causing “some bitterness” among student organisations, but dissent was muted. The vision was compelling, the democratic process seemed sound, and trust in Ylva’s expertise ran high.

When our SU study tour visited HYY and New Student House early in 2020, I was so tired that some of the delegates on the trip managed to convince me that a piano on the top floor had been the one used to compose Lordi’s Eurovision winning “Hard Rock Hallelujah”.

But I’d also been convinced by the ambition in the slides from Ylva’s CEO. This was a students’ union that was about to put its enormous wealth to work – saving money for students, protecting and extending its ethical restaurant business and funding projects like the SU’s visionary “World Student Capital” project.

At the time, HYY was terrified that Prime Minister Juha Sipilä’s (Centre) government was planning to abandon the SUs’ automatic membership – which would have led to drastic cuts in operations.

The idea was that if we own real estate in the best location in Finland, why still collect a mandatory membership fee from low-income students?

Who wouldn’t have voted yes?

The unravelling

Of course just weeks later in spring 2020, COVID-19 reached Finland. Hotels emptied, UniCafe sales collapsed 90 per cent, and the wider hospitality sector – core to both projects – imploded. In autumn 2020, Kerppola left his CEO post to found his own property company, Sfääri.

I felt I was leaving the company in good hands in a good situation, even though the pandemic had already started and the buzz had somewhat subsided.

His departure announcement praised his stewardship:

Ylva’s net assets grew from 160 million euros to 260 million euros, with total assets doubling.

His replacement, Leea Tolvas, brought strong property credentials but inherited a deteriorating situation. She told Helsingin Sanomat – Finland’s newspaper of record and largest daily – that Ylva’s equity ratio would hit 42-43 per cent at its lowest, though HYY’s strategy required it stay above 50 per cent. By year-end 2021, it had collapsed to 28.1 per cent.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine, construction costs soared, and interest rates – the foundation of the entire strategy – rocketed from near-zero to 5-6 per cent. Projects viable at 1 per cent financing became unsustainable at 5 per cent.

Henna Heino, serving on a later board, recalls:

By our term at the latest, we realised the situation was deteriorating rapidly. We tried to handle things in a controlled manner so there wouldn’t be some catastrophic explosion. But by late in the year, we noticed we were going down faster than intended.

By June 2024, Ylva’s annual report showed 74 million euros in losses and 267 million euros in debt. For a company with 33 million euros revenue, the numbers were catastrophic. The report said:

Events and circumstances indicate such material uncertainty that may give significant reason to doubt the group’s ability to continue operations.

Suddenly, there was a real risk of bankruptcy.

Ylva had breached its banking covenants – loan agreement terms – for years. Banks had backed off through to September 2025, demanding a debt restructuring plan. Mika Perkiö, who had taken over as Ylva’s CEO in late 2024, told Ylioppilaslehti that “negotiations had progressed well” but couldn’t comment on content or outcomes.

By spring 2025, Representative Council group chairs were holding marathon meetings – “multiple sessions totalling several hours” – debating what could be sold. Initially, they discussed whether to sell New Student House or Old Student House. “There was no clear consensus,” sources told the student newspaper. Eventually they realised:

We’ll probably have to sell both anyway to overcome the financial difficulties.

Seppo Villa, a professor of commercial law at Helsinki University, had earlier told the paper that if lender banks demanded sale of collateralised properties, “the Representative Council’s decision would have no actual significance.” The banks would force liquidation anyway.

Across 2024-25, Ylva contacted approximately 80 investors across Finland and abroad. Multiple offers came in, but as Kauppalehti – Finland’s leading business newspaper – reported, “the price level in many offers remained below desired.”

After negotiations, Keva emerged as partner, along with co-investors Mrec Investment Management Oy (a Finnish real estate fund manager) and HGR Property Partners Oy (a Helsinki-based property investment firm). Initially, Old Student House wasn’t supposed to be included. It was added during autumn negotiations.

Then last December, HYY’s Representative Council made a brutal decision – cut services and raise the mandatory membership fee 50 per cent from 57 euros to 85 euros to cover an 820,000 euro budget deficit. It was the opposite of everything they’d promised. As is so often the case, students who were in secondary school when those investment decisions had been made would now pay for them.

The final night

On Wednesday, November 13, 2025, HYY’s Representative Council convened for an extraordinary session. The meeting, held behind closed doors citing business secrets under the Act on the Openness of Government Activities, stretched over five hours.

There were big decisions to make. Sell Vanha and Uusi ylioppilastalo – HYY’s historic Old and New Student Houses on Mannerheimintie, Helsinki’s main boulevard – along with Citytalo, Kaivotalo, Hansatalo, and the Grand Hansa hotel complex, all part of their Kaivopihan property cluster in the Kaisaniemi district near the central railway station.

The buyer was Keva and partners, for approximately 187.7 million euros – roughly 100 million euros below the 288.4 million euro valuation from just a year earlier.

Perkiö (Ylva’s CEO) was blunt in the post-meeting press conference:

The alternative was bankruptcy, and that would have meant losing absolutely everything.

The vote was unanimous. As one board member noted, what choice did they have?

Petra Pulli, serving as HYY Board Chair during this crisis year, added:

The most important thing for us has been that we can secure the student union’s diverse student life and organisational activities.

Carl-Henrik Roselius, Keva’s property investment director, acknowledged the cultural weight:

Keva understands Vanha ylioppilastalo’s cultural-historical significance and value. We have begun exploring the possibility of selling Vanha ylioppilastalo’s culturally-historically valuable parts to, for example, the consortium that Helsinki University has been assembling.

What students lost

On Thursday, November 14, students climbing the steps to UniCafe in Kaivopiha were processing the news that had been reported across Finnish media. Helsingin Sanomat had broken the story late the previous night. First-year student Helpi Kyllönen commented succinctly:

Not nice.

Veera Kankainen, a social studies student starting her 20th birthday with lunch at UniCafe, gestured across Kaivopiha towards the New Student House:

All the parties and celebrations are organised there. Of course, I’m worried that all my places will be lost.

Kukka Corander, studying social sciences and management, had been following the news since bad news began from Lyyra:

It is known that it took 150 years to acquire wealth. Anyone who understands anything about management knows that even huge wealth can be lost in a very short time.

Corander remembered attending an event at the Old Student House themed “the city of the future”:

It never even occurred to me at the time that something like this could happen.

Tuomas Salonius, studying pharmacy, reflected on the membership fee increase:

There were dreams of dropping the membership fee to zero. But then everything was thrown away. I wish that for 85 euros I could get services that I would benefit from, and that it wouldn’t all just go to paying off old debts.

Rudolf Heiskanen, a Bachelor of Agricultural Science student active in student life, feared for the future:

Sales are a sad thing when there aren’t many other facilities. The University of Helsinki has also reduced the facilities available to student organisations.

Over 100 student organisations will lose their spaces in the New Student House. These weren’t just rooms – they were infrastructure for autonomous student organising. Offices where student newspapers were produced, rehearsal spaces for music groups, meeting rooms for political societies, storage for decades of accumulated equipment and materials.

HYY had provided these organisations with comprehensive infrastructure – legal advice, specialist staff for guidance, operating grants, facilities including meeting rooms and saunas, equipment rental. Now those organisations faced six months to relocate to Domus Gaudium in Leppäsuo, with 1,400 square metres of space to replace what they’d had in the city centre.

Learning lessons

In the aftermath, a narrative has begun to form in parts of the press – naive students play property developer, make risky decisions through messy democratic processes, and lose everything through incompetence. Democracy, this story concludes, simply cannot handle serious business decisions.

But it’s just as easy to conclude the opposite. In some ways, this wasn’t too much democracy – it was not enough, combined with corporate governance structures that prioritised growth over institutional resilience.

In recent decades, decisions had come to be made by small “work committees” (työvaliokunta) consisting of the chair, vice-chair, and heads of financial committee and supervisory board, while other board members “found out about things just before deals were made.” The Hotel Seurahuone purchase, for example, happened extraordinarily quickly, with limited board consultation.

Ylva’s board had included heavyweight professionals like Varma’s deputy CEO (Varma being one of Finland’s largest pension insurance companies), Bird & Bird lawyers (a major international law firm), and corporate strategy experts. Students say “they had the greatest expertise, while we were just students” and felt they couldn’t question recommendations from industry veterans. Sara Järvinen, a theology student who served on the board, noted:

It would have been madness for me, Sara Järvinen, a theology student, to say this is complete nonsense.

It’s a story many in both SUs and their universities will be familiar with – the “expert” board members who were supposed to provide oversight but instead drove expansion.

The Representative Council’s 60 members had very limited insight into the deals. Kerppola acknowledged that getting the full Council’s approval for individual transactions “wouldn’t work.” Major financial decisions affecting all 27,000 students were increasingly made by a handful of people behind closed doors.

The structure created a situation where a 60-person Council elected by roughly 32 per cent turnout delegated power to a 12-person Board, which delegated commercial decisions to Ylva’s management and board, guided by professional directors with corporate priorities, making 100 million euro-plus property bets.

So one interpretation is not “too much democracy” – it was importing corporate growth logic into a student organisation without adequate democratic safeguards.

The goal of eliminating membership fees by 2025 required doubling or tripling Ylva’s returns. That necessitated massive property development – hotels, office blocks – rather than the traditional model of student services. The dream was seductive – use the property wealth to make students “free” from fees.

But it required taking on massive debt (275 million euros in short-term loans), betting on hotel tourism growth and office development, operating like a commercial property developer, and professional management making commercial decisions.

The corporate professionals did what corporate professionals do – they saw assets, saw leverage opportunities, saw “value creation.” What they didn’t prioritise was institutional resilience, student voice, or the core mission.

What some say should have happened was more democracy, not less. Major asset decisions should have required Council supermajorities, not just Board approval. Debt limits should have been constitutionally protected, requiring referendum-level approval to change. Regular member consultation on the direction of Ylva’s investments.

Student expertise valued alongside professional expertise – because students understand student needs better than corporate property developers. Separation of powers – because the commercial subsidiary shouldn’t have been able to drive overall strategy.

But we musn’t forget the bad luck. No investor anticipated COVID-19, followed immediately by Europe’s largest war since 1945, followed immediately by the fastest interest rate rises in decades. There aren’t any professional property developers who saw that coming.

And anyway, nearly everyone involved insists they’d make the same decisions again. Jane Kärnä:

It feels really awful that we couldn’t guarantee current students better or even the same as what we received from the student union. But still, everyone says that if they could go back in time, they wouldn’t do anything differently with the information available then:

Companies are rarely praised for not investing but rather collecting money in reserves for a rainy day.

With the information available then, I wouldn’t do anything differently. Show me the investor who could have anticipated all of this.

It’s easy to point the finger when things go wrong, but these weren’t irrational decisions made through democratic chaos. They were rational decisions made through corporate processes that prioritised growth and leverage, insulated from democratic accountability, that then encountered once-in-a-century catastrophes.

The land beneath their feet

Paula Karhunen’s blog post the morning after the vote was titled “Maata jalkojen alla” – “Ground beneath your feet” or “Land under your feet.” The metaphor was deliberate.

In March 2025, I stated that HYY will fall to its feet despite the debt of the real estate sector. Today, November 13, after the decisions of the HYY representative council, this country should be under its feet. Or at the latest when the overall arrangements to manage the debt are over, and the student union is debt-free. This morning, it may not seem to everyone that HYY has fallen to its feet. Several things are true at the same time and all feelings are allowed.

She acknowledged the magnitude of what was lost:

At the same time, nothing can take away the sadness of giving up the Old and New Student Houses. The student houses have been a place for culture, a home away from home, for being together, for celebrating under the rain, and have offered students a free third space to just be.

But she insisted on what remained:

Next year, HYY’s operations will change, but the student union will remain. Familiar and safe things such as the division of space by students, self-government, the election of student representatives in the administration and deciding on the level of membership fees will continue.

She also noted the civic response:

As Secretary General, I would like to thank everyone who has supported the Student Union during this difficult time. The consortium led by the University of Helsinki to purchase the Old Student House and the support expressed by the Mayor of Helsinki towards the Old Student House and student culture demonstrate a deep understanding of the history of the Old Student House, its significance for Finnish history and the purpose of the house. It is a profound act of civility to strive to preserve the house for future generations of students instead of lecturing the Student Union.

Then came the line about where HYY’s feet actually stood:

Someone may well ask where those feet are. From the Secretary General’s perspective, they are in the membership fee income that is decided by the Secretary General, self-administration and the implementation of statutory tasks.

She’s got a point. After the sales, HYY will be debt-free and will retain Domus Gaudium, Ylva Services Ltd (which runs UniCafe with its 17 restaurants and cafés across all University of Helsinki campuses), and the restaurant business. All HYY’s membership fee income will continue to fund student activities, and the union maintains autonomy over its statutory duties.

They’ve lost the iconic historic buildings but kept operational capacity – vast food services, a modern “student house”, and most critically – financial independence and self-governance.

Once the sales complete, HYY will still support 250-plus organisations with professional infrastructure, operate an actual restaurant chain, provide legal advocacy services through Pykälä, place dozens of trained, paid student representatives throughout university governance, produce civic-scale cultural events like the Grand Sitsit and the Independence Day procession, and maintain specialist staff for educational policy, international students, and organisations.

What’s impressive is that the basic institutional form survived. They didn’t lose their legal status, their statutory role, their democratic structure, their operational independence, or their core mission. They lost wealth and buildings but kept institutional autonomy.

The inscription carved in 1870 still stands on Vanha’s facade:

Spei suae patria dedit/The homeland gave to its hopes.

They are hopes that built an institution that pioneered student health services, created spaces for Finnish progressive culture, provided infrastructure for autonomous student organising, embedded democratic student governance in university structures, and trained generations of political leaders. Those hopes survived civil war, foreign rule, a devastating fire in 1978, and now financial catastrophe.

Carl-Henrik Roselius acknowledged at the November press conference:

Keva understands Vanha ylioppilastalo’s cultural-historical significance and value. We have begun exploring the possibility of selling Vanha ylioppilastalo’s culturally-historically valuable parts to, for example, the consortium that Helsinki University has been assembling.

There’s a chance – just a chance – that Vanha could return to student use through this consortium. But even if it doesn’t, what HYY has built over 157 years wasn’t just buildings. It was a model of student autonomy, democratic control, and institutional capacity that survives.

The elephant has been flattened. But the student republic endures. And it’s hard to believe that it could have happened anywhere else.

We are building the society of our dreams

Parity: Our goal is an equal society. We promote accessible education, adequate income for students, and free public transportation. We want a world where everyone is treated equally, regardless of background.

Education: We believe that the world can be changed through the power of education. Education is not just bookish knowledge, but also an open-mindedness and the ability to apply learned knowledge. We strive to ensure that students have the opportunity to develop these skills both through lectures and by participating in the activities of the university community and society.

Humanity: We need to do well so that we, as students, can build a more just world now and in the future. A happy student life requires good healthcare services, comfortable housing, humane study requirements, and meaningful leisure opportunities.

Responsibility: We believe that Finland should spend at least 0.7% of its GDP on development cooperation, in accordance with UN recommendations. We should actively promote environmental responsibility, set an example with our actions, and take a stand on environmental issues at the university, in the city, and in society.

Courage: We dare to actively participate in the public debate about students and fearlessly address grievances. We are determined to build the society of our dreams and provide our members with opportunities to influence. The world must be changed.