Back in September, the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) collaborative team led a sector-wide conference hosted at De Montfort University (DMU), with 40 different institutions’ representatives from the UK and beyond attending.

The conference was all about block teaching. Helpfully hosted at DMU who have been doing block teaching for over a year, and could reflect on how they have found this method of teaching and learning.

Within this, the conference focused on six themes – assessment and feedback, community and belonging, curriculum design, inclusive pedagogy, student experience, and student outcomes.

In this explainer, I’ll run through each topic covered at the conference. If you want to go into each session in greater detail, you can do so here.

Building blocks

It’s helpful to first explain what block teaching is. Block teaching condenses traditional semester-long courses into focused, consecutive blocks of learning. At its core, the ethos is to give students more time to engage with their learning by studying one subject at a time.

In theory it can lead to faster feedback through more regular assessment and, all importantly, a better life-study balance as it avoids bunching of assessments at the end of the traditional year.

Many SU officers this year have ben interested in making teaching times more accessible for a variety of student groups, like commuters, student carers, the growing numbrs with demanding part time (or almost full time) jobs – the list of the practical reasons to shift to the block in the current context write themselves.

But it’s interesting to understand the research-based pedagogy behind it, particularly if you are an officer trying to convince academics to change age-old modes of teaching.

At DMU, for example, on Law courses each block runs for seven weeks in total – there are six weeks of teaching and one week for assessment. Each student has two hours lectures, two seminars that are three hours each and two hours of asynchronous materials. THis makes up a total of eight contact hours per week per student.

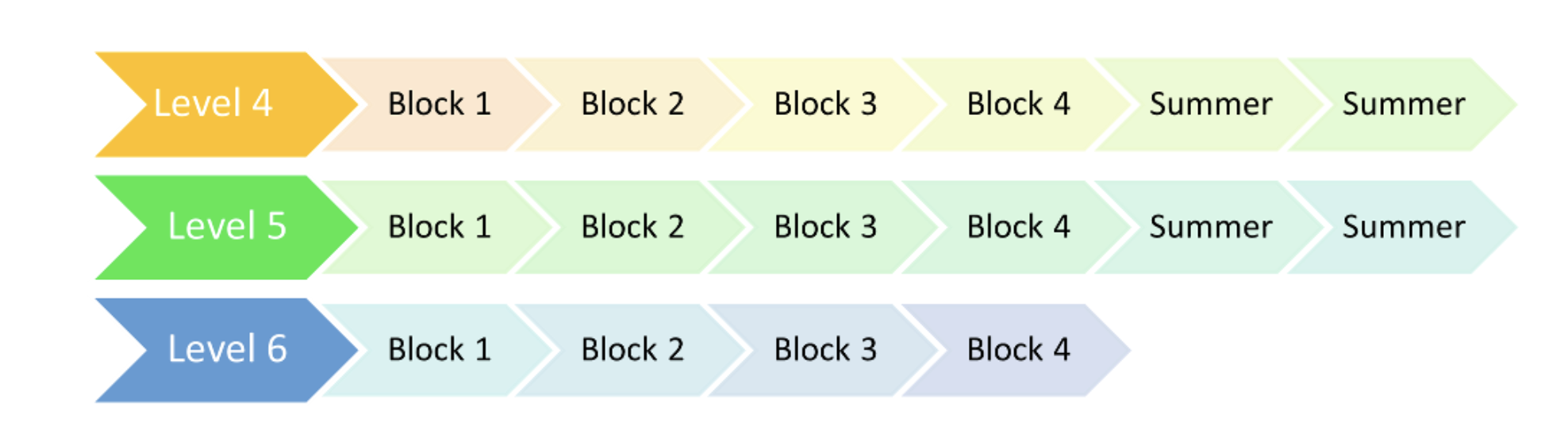

The blocks, aka the modules as most understand them, are all thirty credits and run consecutively. A typical three-year undergraduate degree would be structured as follows:

Curriculum design

The intensity of block delivery provides an opportunity for hands-on development and achievement of learning outcomes, provided these activities are carefully designed during each session in a way that is noticeably different ot the traditional module. Topics should flow sequentially to build upon previous knowledge and promote deeper learning.

Students need to work independently in advance of the session to understand the benefit of this work – and it should be clear where content will require independent learning and not be reiterated in class. Pre-sessional activities can include and reflect real world situations, such as online games, videos, podcasts and reading.

Assessment and feedback

A presentation from the University of Suffolk where a “block & blend” approach was adopted in 2021-22, looked at student and faculty perspectives of co-designing assessment within block teaching methods. The study, made up of a mix of surveys and focus groups, wanted to understand what lecturers’ and students’ perspectives were on assessment types and assessment co-design in a block delivery course.

One finding was assessment, from both groups, was seen as pre-established and unmodifiable and a general perception, from staff, that non-traditional assessment methods were difficult to use.

For instance on a course with professional, statutory and regulatory bodies (PSRB), like nursing, there was a feeling that non traditional methods or block teaching do not work, because it was presumed they could not be done within a week.

There was also a sense that assessment method was linked to the level, module, course or subject area – exams as a way to assess accuracy in sciences, and essays are for arts and humanities subjects. As one put it “in arts and humanities, an essay at L5 is a very accurate indicator of a student’s progress. It may not be the same for science subjects”.

Another concern was time considerations. Single essays or exams at the end of the block were not suitable for block delivery because of time constraints, people saif they felt multiple smaller assessments would be more beneficial and allow students to do more manageable increments of academic work, compared to one singular essay or exam.

But there was a sense that the block teaching method did not allow multiple assessments, usually related to assumptions around multiple traditional summative assessments which increases workload – despite this not always needing to be the case.

Suggesting that a variety of assessment methods – some co-designed with students to help them understand the process and reasoning behind learning objectives and, sometimes, ease workload from staff, is essential to successful block teaching. As well as multiple smaller assessments in-class, which could include automated quizzes so as not to add to staff workload, but will provide different skills for students on the course.

Collaboration between teaching staff was also felt to be essential to avoid the “silo thinking” issue in block and ensure there is continuation between module. Here, synoptic assessment was highlighted as providing a holistic approach that avoid silo thinking and ensure authentic and comprehensive assessment.

If course teams would look holistically at the assessment over the course of a given year and design the individual module assessments to reinforce the key skills students need to develop from one module to another.

Skills-based learning

Following on from the need for academic organisers to work together, the session on designing a skills-based curriculum urged participants to ensure they embed skills-based learning at programme level not module level, lest it get lost and become the job of individuals to “add-on” skills stuff, rather than embed it in from the start.

Programmes with block sequencing makes embedding skills-based learning more practical than in traditional modules because the skill scan be directly linked to the individual learning objectives being developed across the seven weeks. Students are, generally, more aware of the module’s purpose in this intensive version in a way they may not be when taking multiple modules at the same time.

Within learning outcomes, it is important to give students summaries of what skills staff hope they will be improving so they feel confident in having achieved the objectives when they finish the block. Additionally, they are better able to articulate their skills in things like job applications.

Blocking to support transitions

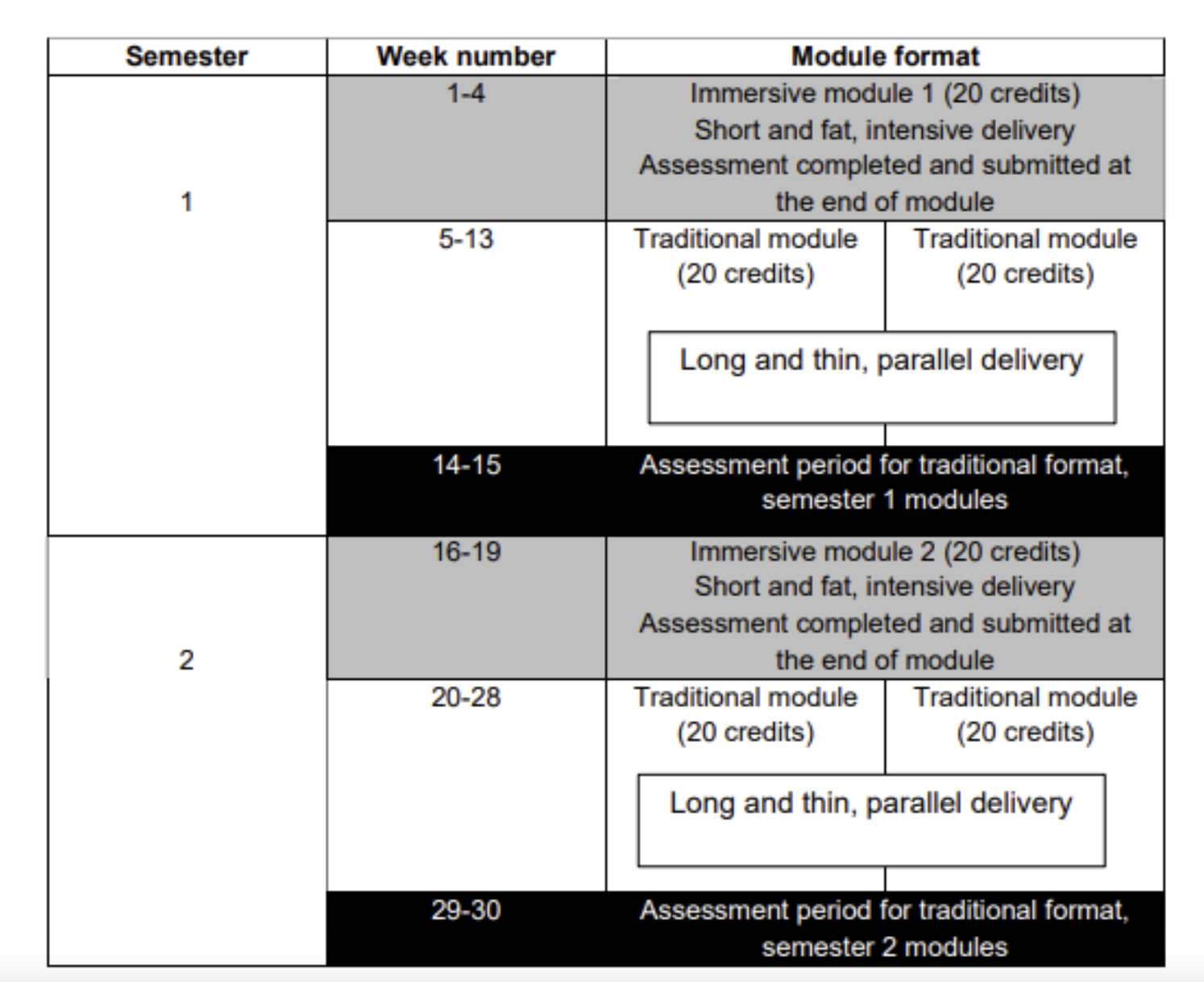

Academics from Plymouth University shared reflections on their move to block teaching or “immersive scheduling” as it’s known at Plymouth. As part of their curriculum enrichment project, they designed teaching blocks that would support first year students to transition into university study.

As part of the first year immersive modules, there would be introduction ot the key principles of the discipline to contextualise the programme to the wider world. Then in semester two, students would have the option of “Plymouth plus” where they could choose from interdisciplinary modules to broaden their knowledge from semester one.

Many students felt this modular approach helped build their confidence both academically and socially. For instance, one student referred to the benefits of sustained exposure to the same peers or academic staff as meaning;

You’re happy to sit with anybody because we all know each other and we’re all friends, and there isn’t a feeling of, you know, ‘I don’t want to sit with them.’ You know, everyone, and I think that has come from those exercises and the way that the module was put together.

Considering conversations SUs are having about creating more shallow ends to help students settle into university and research that suggests students want this induction period to go on longer than just the first week – it’s clear that block teaching may help achieve this aim.

Inclusive pedagogy

One session looked at how staff can make block teaching more inclusive, and many of the principles are similar to this within “standard” teaching practices. Universal design methods are preferred and designing in accessibility from the beginning, rather than adding it in afterwards via reasonable adjustments is always better.

Some of the challenges of block delivery include restructuring from a weekly lecture/seminar format, and consider the potential for gaps in engagement or potential barriers of the new format for learners with diverse needs.

Generally, the micro-learning approach, which sees students learn in more bitesize chunks and focus on one module at a time rather than juggling multiple modules can be more inclusive for many learners.

From initial feedback from the first year “on the block”, students said they preferred “lecturettes” which were short-form video content recapping or summarising the lecture, or that was a recording of the lecture itself. Partly because of convenience, but also the ability to pause, take notes, and relisten to content was helpful. It was also a less overwhelming way to receive content. As a result, grades significantly increased over the previous two years.

Residential learning

One innovative method came from the Dundalk Institute of Technology (DkIT) which saw staff take students on a residential retreat. Initially the preparation sessions were held on campus over three days and run from 9am-5pm. Then, the block sessions were a five day long residential at a retreat centre in Hirschegg, Austria.

Some of the benefits were in its intensity and way students had to quickly adjust to a new way of learning by being pushed outside of their comfort zone. Many felt it became an opportunity to build stronger friendships and make new connections.

But also, given the close quarters nature of the five day retreat, helped students develop conflict management skills to navigate what to do when communications break down, people get frustrated and problems need to be overcome in order to work in a team.

Many students reflected that it felt fun and exciting to be learning in such a different environment. It always allowed them to get to grips with new and difficult concepts in a much more immersive way than in a lecture hall.

Now, not everyone will be able to organise a retreat to Austria for each cohort. But the takeaways of students appreciating intensive, focused opportunities to learn and get to grips with topics. As well as appreciating any opportunity to get out of their comfort zone and learn in a new environment – even if this was just in a different part of campus or the city, could help with overall engagement and create positive memories of their learning.

Read more

Learning in Blocks: Evaluating the Impact of Immersive Learning