Given I’m writing this in late November, you might think it’s a bit early in the academic year to be talking about ensuring that officers have left a lasting mark on the university or the SU.

But I’m not talking about that kind of legacy. I’m talking about funding.

Legacy gifts are when people leave money to the organisation in their will. And over in the main part of the voluntary sector, legacy funding is now one of the biggest growth areas in donations to charities.

In 2020, funding from legacies to charities totalled £3.4 billion – some 16 per cent of all fundraised income. More than 10,000 charities benefit from gifts in wills each year, and charitable will-writing is growing fast, especially in small charities.

A November 2020 report on the issue identifies four key benefits:

- Significant reliable income stream – With potential for a significant and sizeable income stream, legacy income can help charities manage cashflow and make it through periods of instability where more immediate income streams may fail.

- Unique offering for supporters – At a time when charities and communities are in crisis and supporters want to dig deep, but may not have accessible income, a legacy gift can be an even more fulfilling and attractive a proposition.

- Unrestricted source of funds – Predominantly a source of unrestricted funds, charities have the ability to direct monies as needed, whether that may be to underwrite new services or simply to keep the doors open in tough times.

- Long-term planning for long-term solutions – Longer-term income streams enable charities to budget for the future and plan ahead, bolstering reserves to ensure longer-term charitable goals can be met

Wider economics of giving

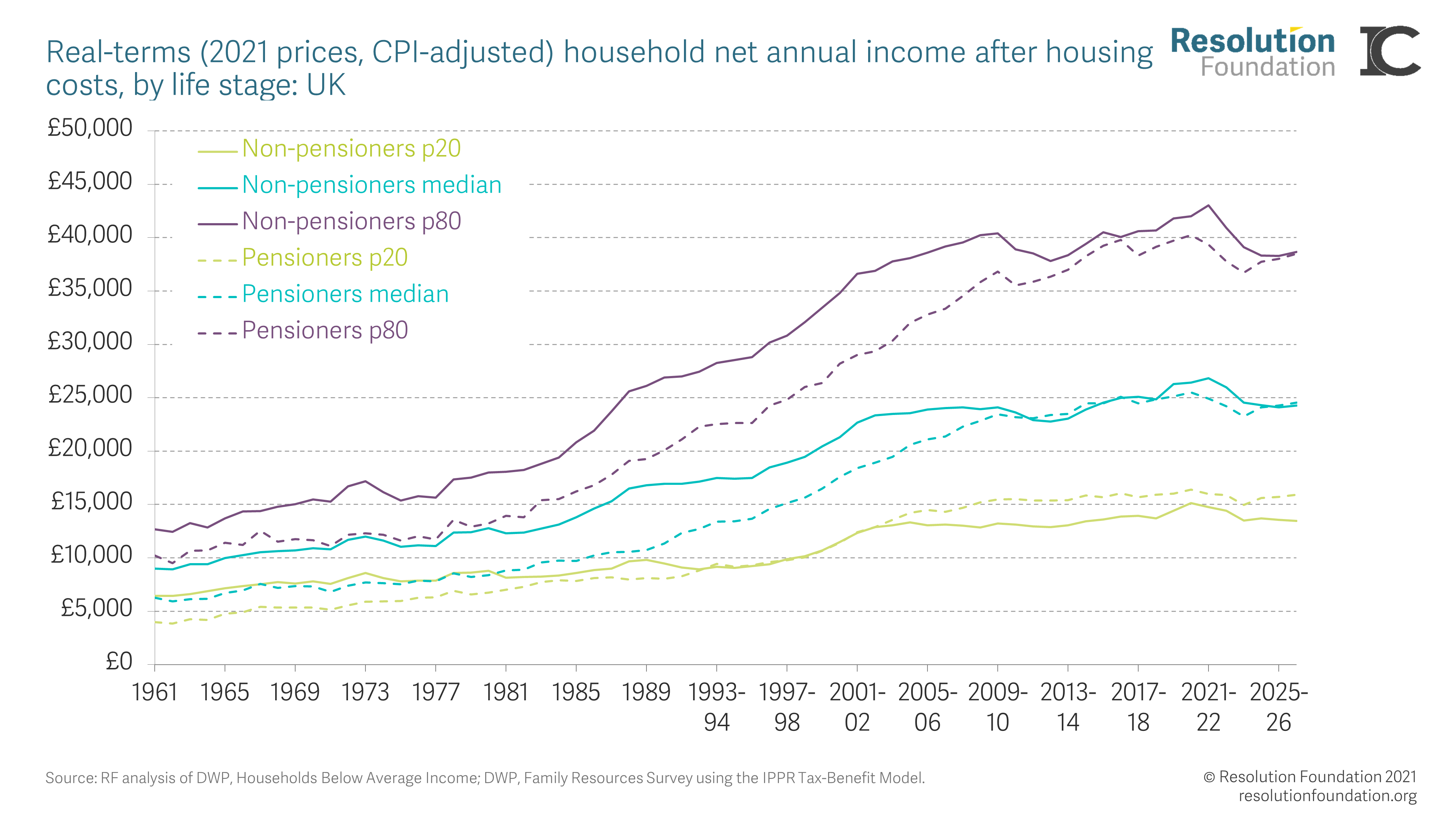

Particularly interesting in this space is the wider economics of giving. General giving to charities has been under significant pressure as the country has lurched from a pandemic to a cost of living and energy bills crisis – but house prices have risen, and the triple lock on pensions has had an effect.

More than three million over-65s are living with over £1m in housing and pension assets, amounting to one in four pensioners, according to research by the Intergenerational Foundation. That number was 846,000 in 2008, which shows how retirement wealth has ballooned over the past decade. According to the Office for National Statistics, almost three-quarters of over-65s own their homes outright and nearly 70% have a private pension.

Currently, around 16 per cent of all wills include a charitable gift. Over the past 30 years legacy income has trebled, and is set to double again over the coming 30 years.

Should SUs do this?

This is not a natural, comfortable or familiar area for SUs. Income in the SU sector is predominantly sourced from a Block Grant (and sometimes string-attached project funding), and commercial trading income. But both are under huge pressure – the former from pressure on the unit of resource, and the latter from the Cost of Living crisis. Some SUs have explored trust grants in the past – but few have ever pursued legacy fundraising.

However in the university fundraising sector, encouraging legacy gifts from alumni is a well-established practice. Almost all universities are engaged in maintaining alumni relationships to this end, and most find that attending the university was an important aspect of a donor’s life that they often wish to “pay forward” to the next generation. That begs the question – who are SUs’ alumni?

There have been students’ unions in universities for a long time, and there have been members who have benefited from SU activities, services and campaigns throughout that time. But with notable exceptions, most of the students (and now alumni) in that category were students in general too – and would be likely to engage with the university centrally and directly over any legacy fundraising.

But we are now entering a specific period in the history of SUs. Full-time, sabbatical officers only really started to emerge in the 1970s – a generation of student leaders now likely to be finding themselves in their seventies. Many will be squeamish about considering this – but in the wider legacy fundraising sector discussions with potential donors begin in earnest with people in their fifties and sixties.

And it’s sabbatical officers who are likely to have had the most profound experiences, and may be interested in furthering the work of the SU for the next generation.

How to go about it

In this blog legacy fundraising expert Claire Routley talks about how smaller charities are approaching legacy fundraising, and offers some tips:

1. Pull together the information a potential legacy donor might need

Even if you don’t actively promote gifts in wills, and even if you intend to do no other legacy promotion, it’s a good idea to have the information someone might need if they come to your organisation proactively. Indeed, not having access to the correct information has been proven to be a real bugbear for solicitors supporting people who are writing charities into their wills.

Helpful information is likely to include your official name, address and registered charity number. It’s also a good idea to think through whether you’re happy to accept restricted gifts i.e. those that must be spent on a specific project, and what kinds of projects you would be comfortable enabling a donor to focus their gift on. Are you likely to still be running the same kind of work in 10-20 years, for example?

2. Add a line about legacies to your literature

Whenever you’re reprinting or developing materials for various audiences, including a line about the importance of giving in general and legacies in particular is identified as important. You might, for example, include something like “XYZ organisation is a charity, and we rely on donations and legacies”. Often people don’t realise that SUs are actually charities, or that it’s possible to support them philanthropically, so this approach could benefit getting the message out there about legacies to friends and family.

3. Approach those who are closest to you

One of the most powerful ways of talking about legacy giving is through case studies of what other people have done. For small charities, this can become a bit of a chicken and egg scenario – they’re just getting started in the area so don’t have donor case studies. External trustees can be a great place to start. If they include the charity in their wills, they can share their story with others through charity communications such as the website, social media and talks in the community. Their gifts don’t have to be particularly large – it’s their story which really matters.

4. Tell stories

Linked to point 3, story-telling more generally is a great way to encourage people to think about gifts in wills, whether that’s stories about people who’ve died and the difference their gifts have made, stories about work funded by legacy gifts or stories about people who plan on leaving a gift in the future. Talking about legacies through stories is a really gentle way to introduce the idea of leaving a gift and can take the fear out of talking about something which involves the taboos of death and money.

5. Encourage colleagues to talk about legacy giving

The legacy giving message can be amplified many times over if all the staff, officers and volunteers in a charity are confident to talk about legacy gifts. Normalising the idea of legacies as a way to support your organisation for your colleagues and providing them with some training to increase their confidence around the subject.

What should or could SUs do?

The volume of potential donors may not – at least for the next decade or so – be sufficient to support individual SUs recruiting or paying for dedicated legacy fundraising capacity focussed on sabbatical alumni. But the opportunity points towards a need for:

- SUs to identify (all of) their sabbatical alumni, going back as far as SU sabbs go, and identifying their career trajectories and successes in wider society;

- Developing a relationship with sabbatical alumni – considering events, meetings, tours and other forms of engagement to build a long-term relationship;

- Collaborating over external legacy fundraising capacity to convert relationships to entries in wills, either for restricted project purposes or unrestricted funding

This also points to a set of wider questions about sabbatical alumni. In Finland, there are both national and local student leaders’ alumni associations that help gather the skills of those now in industry and politics – to support current students’ unions in tough financial times and to provide pro-bono consultancy and mentoring support.

Establishing a pattern of “paying it forward” may not be helpful just for legacies – it could help provide access to the sort of advice and support that many SUs are likely to find difficult to afford in coming years, and give alumni something more rewarding and productive to do than being an external trustee.

We’re going to hold a round table for any SUs interested in this work at 2pm on Tuesday 13th December – to identify if there is scope for collaborative work on sabbatical alumni relationships relationships generally, and legacy fundraising specifically. Do join us.